Читать книгу Stargazer - Jan van Tonder - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

Оглавление“Life isn’t a story, Timus, how often do I have to tell you?”

You could see Pa wasn’t used to being barefoot. His toes kept trying to escape from the grass. They were almost as white as the plaster cast on my arm.

“Do you hear me, Timus?”

“Yes, Pa.”

“What did I just say?”

“That life isn’t a story, Pa.”

“Look at me when I’m talking to you.”

It was hard to look at Pa when he was angry. Ordinarily his eyes were light blue. But when he was angry it was almost impossible to see where the white ended and the blue began. I always expected to find one eye fixed on mine, with the other one looking me over from head to toe, searching for something else that might be wrong.

It was bad enough not liking what you saw every time you looked in the mirror. The good Lord had chosen me to be left behind. All my friends were ahead of me. Miles ahead. Voices broken, hair all over their armpits and faces, huge willies. But it was better to avoid that subject altogether.

“How you expect us to believe a single word you say, I can’t imagine. The stuff you come up with . . . We lie awake about you at night, Timus, your mother and I.”

Pa wasn’t one to tell a lie, but that bit I didn’t believe: him lying awake about me! Ma, yes, but not him. “Stop worrying, Vrou, children grow up by themselves,” he said when Ma imagined the worst possible tragedies, as she always did. She said he was asleep before his head touched the pillow, and he woke up only after he’d taken his first sip of morning coffee. That was because his conscience was clear, Pa said.

“You don’t exactly make things easier for us, Timus.”

I nearly told him it was Joepie’s mom who’d made things difficult for us this time, not me. She was the one who wouldn’t let sleeping dogs lie.

When Pa and the others came back from the farm and saw my broken arm, Braam was quick to say: “He was just running and he fell, Pa.” Braam is my brother. He’s a lot older than me. Ma shook her head: “You’ll be the end of me yet, Timus. Why must you be so wild?” Pa said children’s broken limbs mend fast, she needn’t worry.

No one mentioned it again till Joepie’s mom turned up, doek over her curlers, apron still tied around her waist. When Ma saw her at the garden gate, she took one look and said you could just see that woman’s tongue was itching, she was so keen to pass on some or other story. Ma might as well have given me permission to eavesdrop.

Joepie’s mom wouldn’t even sit down. A hurried greeting and she plunged straight in. “I’m here to do my Christian duty, Abram. You know I don’t usually stick my nose into other people’s business, but I just couldn’t bear this burden on my own any longer. For the past two weeks, ever since you came back from the funeral, my conscience has been giving me no rest.”

She told Pa how she’d seen me come running home, covered in blood, clothes torn, with a broken arm. From the direction of the vlei. And who knew what had happened to me there. And on a Sunday as well.

Pa rapped on my cast with the knuckle of his middle finger. “The only reason why I’m not going to give you a hiding is that the Lord has already punished you. When are you going to learn some responsibility, Timus?”

I blinked. Again. Could it be? The pupil of one eye remained fixed while Pa’s other eye was moving: down, down, till it reached my feet, then up to my broken arm, then back to my face. So he’d finally managed it, after all this time.

“Timus,” he said, “what are you thinking right now?”

“I’m concentrating on your words, Pa.”

“What did I just say?”

“That you have a clear conscience, Pa.”

“What?” He was furious. “Go to the bathroom! I see words are wasted on you!”

The bathroom meant a hiding. Ma would’ve said there’s no two ways about it. And all I’d done was tell the truth about how I’d broken my arm. Not that it had been my idea in the first place.

Pa sent you to the bathroom and then watered the lawn while he thought about how many strokes would be a suitable punishment. He didn’t want to strike you in anger, he said. While you were waiting, you thought about all kinds of things just to try and forget where you were and why. Much later Pa came in and closed the door and sat down on the lavatory lid. First he looked you in the eye and talked to you. Then he thrashed you.

You could scream all you liked, he never gave in – he delivered as many strokes as he’d decided on. But on those occasions when he’d made up his mind not to give you a hiding, he’d look at you and look at you until you wished he’d rather just thrash you and get it over with. And when he left, you locked the door and sat on the rim of the bathtub for half an hour, too ashamed to come out.

The waiting was always the worst for me. Everyone in the house knew what was coming, and so they were quiet, like people at a funeral. You could hear the locomotives and electric units at the loco, and from other backyards you heard the laughter of children who weren’t waiting for a hiding, and sometimes Riempies would brush against your legs, completely unaware that soon those very legs would be on fire.

There was nothing to do in the bathroom. It was easy for Pa: he was outside with the garden hose in his hand. If he liked, he could put his finger across the tip and spray the water so that you could see a rainbow against the sun. Or he could see how far he could make the water spurt. I knew how far: past the topmost branches of the wild fig in our back yard. I’d never seen such strong water anywhere else. It was because we lived in a hollow, Braam said. If you walked from our place up to where Lighthouse Road met Bluff Road at the top, and then carried on along Bluff, up the hill, right up to the top where it began to descend towards Wentworth, you came to a water tower. It was an enormous thing – you could see it clearly from below. That was where our water came from, along a thick pipe that passed under the road, and from there thinner pipes brought the water to the houses. If you left the hose on the ground and you opened the tap wide, a jet of water spurted out that made the hose swing from side to side, standing up and falling down like a thing about to strike.

We would jump over it and duck and try not to get wet, but often the hose would twist suddenly and then you’d be hit by an icy blast. When Ma saw this, she’d shut off the water. “It’s only people who don’t do their own washing who’ll play in the water like this,” she’d remark.

In the evenings after supper Gladys fetched hot water for her bath. There was only a cold shower in her kaya. First she fetched her food and stacked the dirty dishes in the oven to wash them the next morning. Otherwise her day was too long, Ma said. By the time she came for her bath water, it was dark outside. One evening I set a trap for her. As she came walking back to her kaya with the bucket balanced on her head, I opened the tap. Shhhh! said the hose. Gladys stopped in her tracks. All of a sudden the water spurted and the hose began to swing to and fro. Gladys screamed and dropped the bucket. Before I could shut off the water, Ma was standing in the back door.

I got a hiding, of course. Ma was furious. “There could have been boiling water in that bucket – what then?”

“She never fetches boiling water, Ma.”

“Never mind. She’s a grown-up. If you want to scare someone, try someone your own size.”

I didn’t say so to Ma, but no one I knew – not Joepie or Hein or anyone else – would’ve got such a good fright as Gladys did that evening. Some day soon, I promised myself, I’d scare her right out from under her bath water again.

Luckily it was Ma who dealt out the punishment that day. She’d get angry and grab a strip of wood from a tomato box and deliver a few smart whacks and it would be over and done with. Not Pa. He gripped your hands behind your back and used his other hand to wallop you on the thighs. There are few things harder than the hand of an operator, and Pa’s hand was almost as hard as the plaster cast on my arm. That was why I was sitting in the bathroom, after all. Not because of Pa’s conscience – because of the cast.

People had a way of noticing the cast and wanting to know why it was there.

“Hello, Timus, and that cast?”

Not how are you, I’m well, thank you. No, it was always: And that cast? Or: Did you break your arm? Or: Must be quite hot under that cast, Timus. Why wouldn’t it be? Durban was hot enough as it was. And from the sweat and the bath water the cotton wool under the cast gave off a stench about as bad as the whaling station.

Braam said I should say no, there’s nothing wrong, I just felt like not being able to scratch my arm where it itches, so I had the cast put on. But it was easy for him to talk. He wasn’t going to be stuck with this thing on his arm at Mara and Rykie’s party.

Mara and Rykie would soon be turning twenty-one. They’re twins. Mara wanted a party. It was all she went on about. Rykie wasn’t so keen. The trouble was, Rykie was pregnant. It was a terrible thing in our home, Rykie with a bun in the oven. At first Pa acted as if she no longer existed. No one dared mention her name to him. Then the girls said, well, if we can’t talk about it, we’ll just have to laugh about it.

“Just imagine: the birthday girl at her twenty-first with a huge stomach,” Rykie complained whenever the party was mentioned.

It made me feel better about my arm. At least I wouldn’t be the only one with something no one could miss.

Anyway, there weren’t going to be any girls at the party. Only Mara and Rykie’s pals and boyfriends and so on. Probably Joon as well. Pa said even if Joon had the humblest of jobs, he, Abram Rademan, would allow a daughter of his to marry him any day, for Joon was a godfearing young man with a gift for leading people back to the straight and narrow.

Joon was a callman. He saw to it that everyone was awake in time for his shift. He had a book wedged in the carrier of his bike with everyone’s names: firemen, drivers, shunters, ticket examiners, wheel tappers. He knew the time each person had to report for work. After knocking and waking someone, he would hand him the book through the bedroom window. Then that person had to sign next to his name. That way, no one who was late or missed his shift could blame Joon for not letting him know it was time to go to work.

Ma said if callmen didn’t do their work, the entire SA Railways and Harbours would come to a standstill. But the Railways had nothing to fear – not as long as Joon was our callman.

Joon was Aunt Rosie’s son. Aunt Rosie went up and down the streets all day long, picking up stones. She put them in a bag that hung from her shoulder. Sometimes people made fun of her in passing: “Pick ’em up, Auntie, pick ’em up,” they’d say. Ma scolded if she heard me doing this. Her guess was that Aunt Rosie picked up those stones so that people wouldn’t throw them at each other. But no one really knew why she did it. And even if you asked her, she wouldn’t be able to tell you. Aunt Rosie was a mute.

Sometimes I wished I couldn’t speak, then my mouth wouldn’t get me into so much trouble. After all, I wouldn’t have been waiting here in the bathroom if I’d kept my mouth shut.

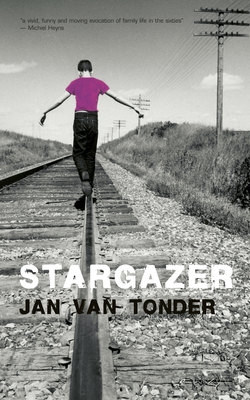

Anyway, Aunt Rosie was Joon’s mother and Joon was cock-eyed. He didn’t just have a squint like other people. No, he had to tilt his head right back to see where he was going. That was why people who didn’t like him called him Stargazer. I wondered how he was going to dance at the party without stepping on the girls’ toes.

Then again, it was still not certain there would be any dancing at all, because Pa said not under his roof. He said you could be young in a decent way, without dancing. Mara said in that case she’d been young in a decent way long enough. “One of these days I’ll be old, like you, Pappie, and then I won’t feel like dancing any more either, and then it’ll be easy for me to say it’s a sin too.”

She was cross with Rykie as well, because she wouldn’t help her stand up to Pa about the dancing.

“As if he’ll listen to us,” Rykie grumbled.

“It doesn’t matter. We must support each other!”

“It’s different for me, Mara. A pregnant woman can’t twist and rock ’n roll, you know. I’ll look ridiculous.”

“Now you’re a woman all of a sudden. Hmph! It’s not only the party, Rykie. What about all the rules in this house? Why is it that even though the two of us have finished school, if a boy comes to call, he has to leave by ten? I could die of embarrassment.”

I’d feel the same if it was me. At ten sharp Pa would call out: “Bedtime!” And five minutes later he’d be standing in the door of the sitting room in his pyjamas, waiting for the boyfriend to leave by the front door. There wasn’t even time for a goodnight kiss.

“If we stick together, we have a chance,” Mara said.

Rykie put her hand on her heart. “I’m never going to kiss a boy or let anyone near me again anyway, that’s a promise.”

“Now I have to suffer because you bloodywell . . .”

“Ah-ta-ta-ta-ta!” Ma warned and I couldn’t hear the rest. Mara’s face was red. Rykie began to cry.

Long after the girls had made up, Mara was still angry with Pa. And he was like a thundercloud, no matter how hard Ma tried to keep the peace. Fortunately someone phoned just then to say Oupa Chris had died, and Mara’s party was forgotten for the moment. But then it was my turn to sulk. They wouldn’t take me along to the funeral because it was during the school term.

When Oupa was still alive, we used to visit him and Ouma Makkie on the farm every year. In Ladismith in the Klein-Karoo. While Ma was baking for the train journey, she’d always say she wished for just once in her life she could go on a real holiday, not a visit to family. But to me the farm was the best place in the world and the journey by train to get there was just as good. It took three days and three nights. The best part was the sound of the 16E locomotive of the Orange Express at night. Bongolo, they called him, which means donkey. Gladys said it’s actually imbongolo. But the 16E didn’t sound like a donkey at all. There was no other locomotive with a beat like that. On the second evening we’d stop at Kimberley, where Tannie Toeks and Oom Neels lived. Tannie Toeks was Ma’s sister. She wore fancy clothes and her hair was always nicely done. Tannie Toeks was an educated woman. She and Oom Neels always came to the station with all kinds of nice things to eat, and they’d stand talking to us at the window of our compartment. When the train left, Ma would wipe her eyes.

Erika and Martina, my other twin sisters who were still at school, were lucky. One of them was allowed to go to the funeral, and they could choose which one themselves, as long as there wasn’t a fight, Pa said. The one who went along could catch up her school work from the other one when she returned. But later Pa changed his mind: Erika had to go, because she and Sarel were madly in love and that wasn’t a good thing. Mara and Bella and Rykie stayed behind because they had to work and, anyway, they were too old to travel on Pa’s free pass.

Braam wanted to pay for his own ticket, but Pa asked him to stay because there had to be a man in the house, after all.

I begged Pa to take me along, but no way. Because of my school work. Come to think of it, this hiding was actually Pa’s fault because he was the one who’d left me at home.

“You’re already so far behind, what with your dreaming,” was all he said.

I had reason to be fed up. After all, it wasn’t my fault that I didn’t have a twin like all the others. I knew how it happened too because I overheard Ma tell Tannie Hannie one day when she came over. At the time Tannie Hannie and Oom Stoney hadn’t been living in the house behind ours for long and she and Ma didn’t know each other as well as they did later.

“First it was Mara and Rykie, then Braam and Bella, then Erika and Martina. I had to put a stop to it, Hannie, you don’t know what it feels like.”

“And I have no desire to find out, Ada.” That was Ma’s name: Ada. “No, really, sometimes it’s too quiet for me, you know, with only the two of us in the house, but I can’t imagine how I would’ve coped. It’s bad enough when they’re small, but five grown-up girls in one room, sharing beds and wardrobes – no, thanks, it’s a recipe for disaster.”

“Like I said, Hannie, once the six little ones were there, it should’ve been the end. But five years later, when I believed that at last, thank the Lord, I was too old and it was all over, there I was: pregnant again.”

“Men don’t know the meaning of the word enough, do they?”

“You can say that again.”

“Look, the only time I still allow Stoney near me is when he wants it so badly that others are starting to notice.”

Ma laughed. “Well, my dear, I couldn’t put the blame on Abram. He was away all week and on weekends I was only too grateful for the extra pair of hands.”

“I don’t know how you coped, Ada.”

“There’s always a way, Hannie. When the two new babies were hungry at the same time, I’d sit down to feed them, and the others could cry all they liked – it was my time out.”

I sat on the steps outside, listening. They didn’t know about me. I was counting Snippie’s teats. Her belly was swollen with puppies, in spite of all the cups of boiling water Ma had flung through the window to chase off the dogs.

“Later the older ones were big enough to help me with the little ones, otherwise I don’t know what would’ve happened when I fell pregnant again. I was very big, and for months on end I prayed, pleading with the Lord not to give me twins again.

“But I’m telling you, Hannie, when your troubles are at their worst, your prayers are always answered. Only Timus popped out. On his own. The only one of my eggs that wasn’t a double-yolk.”

Double-yolked eggs! That was another thing I’d never been able to work out, even though I had five sisters, two eyes and two ears. The girls were always pretending I wasn’t there, they said all kinds of things in front of me, just like Ma and Tannie Hannie, or they ran from the bathroom to their bedroom with no clothes on when they knew there was only me in the house. But no matter how closely I watched them from the corner of my eye, I’d never managed to see an egg of any sort on any of them.

“Timus arrived by himself, but believe me, Hannie, after he was born the least little pain had me in a flat spin – had Timus really been in there alone, I wondered, or was there another surprise in store for me? It was weeks before I relaxed completely.”

They laughed till they cried.

Ma took a hankie from her sleeve. “When the doctor asked me what I was going to call him, I just shrugged. All through my pregnancy I’d been so terrified that I’d clean forgotten I’d have to name him.”

“And then, Ada?”

“Why don’t you call him Septimus, the doctor asked. And even though I knew perfectly well there’s never been a Septimus in our family, I told Abram that’s what we’re going to christen this child.”

“You were probably so glad there was only one, you’d have called him Hendrik Frensch if the doctor had suggested it.”

“Hmph!” Ma replied.

Hendrik Frensch – those were Doktor Verwoerd’s names. I wouldn’t have minded if they’d called me that. Neither would Pa. He voted for the National Party. He was a Nat. But I wondered if it would’ve been quite so easy for him to give me a hiding if he’d had to say: Go to the bathroom, Hendrik Frensch!

One Sunday during the time Ma and the others had gone to bury Oupa, I went to the vlei. On Sundays we weren’t allowed to go to the beach or the woods or the vlei. We had to be quiet. In our own yard. And that was where I’d intended to stay that Sunday while Pa and the rest were away, but then the church Bantus came past our house with their long robes and drums and things and suddenly I remembered the place in the woods I’d seen a while before. A place that had frightened me.

I came across it while I was looking for avocados for Ma. Every tree I knew had already been stripped, but then, in one of the densest parts of the forest, I found a big tree with lots of fruit. I’d never have known about it if the monkeys hadn’t led me to it.

Those monkeys appeared suddenly, out of nowhere. At first I was scared. But when they scattered into the trees I followed them along a footpath through the woods. They veered from the trail, swinging along the treetops, and I had to crawl through the underbrush to see where they were going. It was dark on the forest floor. The earth was moist. Then I reached a place where I could stand up straight. The monkeys had disappeared, but right in front of me was the biggest avocado tree I’d ever seen.

It was a silent and lonely place and I was scared. If someone killed me right there, no one would ever find me, I thought. I didn’t quite know where I was. All around me were shrubs and dense thickets and monkey-ropes and other vines. To tell the truth, I was lost. My stomach began to churn. Then, suddenly, I thought I heard the whistle of a locomotive, and immediately I thought of Joon. When I heard the din of the loco, I always knew that people were working there because Joon had woken them up. And when I thought of Joon I was no longer afraid.

I climbed the tree and crawled along an overhanging branch. When I emerged above the treetops, I couldn’t believe my eyes: only a few hundred yards away were the vlei and the shunting yard and the loco with its rows of trucks and locomotives and electric units. In the distance I could see the compound where the Bantus lived who worked at the loco. Only then did I notice all the avocados hanging from those branches. I picked one and was just letting my arm dangle to see where I could drop the fruit without bruising it, when my fingers suddenly refused to let go – almost directly below me I saw a clearing where the grass had been completely flattened in a large circle, like underneath the swings in the park near the school. Inside the circle the grass grew tall and straight. Around the edges it was flattened. I just knew it was the church place of the Bantus.

Ma didn’t want us to say kaffir – she said they were Bantus. Ma supported the United Party. She was a Sap. She said all people had rights. When Bantu people did something she didn’t like, she called them wretches or creatures.

I went home carrying only that single avocado pear, because it seemed to me I had no right to have been at that church place. The hairs on my forearms were standing on end. But that Sunday when the Bantus came past with their drums and fancy clothes I couldn’t have been thinking straight and so I took the shortcut to the vlei to wait for them there.

I climbed the avocado tree and lay on the overhanging branch, directly above the dancing circle, and waited. The church Bantus were walking through the vlei in single file, coming closer and closer. When they halted opposite me I felt trapped. I wanted to climb down, but it was too late to escape. One by one they approached the circle along a narrow footpath, brushing through bushes and branches till they were directly below me. If you didn’t know about their path, you’d never find it.

They seated themselves around the edge of the circle, and I realised why the grass was so flat there. One man began to pray. He spoke in a loud voice. Spit flew from his mouth and clung to his beard. My body was aching, but I didn’t dare move, even though everyone had their eyes closed.

“Amen,” said the man, and they started to sing. The drums had been placed to one side – oil drums with their tops and bottoms sawed off, the openings on either side covered with cowhide, stretched tight with leather thongs. I wished they’d beat those drums so that I could move on the branch without being heard.

A baby began to cry and his mother unbuttoned her dress to let him drink. No one batted an eyelid. I’d seen a woman do that before: when Boytjie was still drinking from Gladys. But she always covered herself with a blanket when Pa or Braam was near. Boytjie was Gladys’s child.

At last they started beating the drums: ke-boom, ke-boom, ke-boom-boom-boom. A few got up and danced, round and round the flattened circle. Very carefully I tried to shift my weight on the branch. Chips of bark fell to the ground. I was petrified.

One of the men, the one who’d been praying, suddenly spoke in a loud voice. Whether he was preaching, I couldn’t tell. Every now and again he threw back his head, as if to look up, but his eyes remained closed. The drums were still beating and the man’s voice was growing louder and louder. The drumbeats seemed to pass right through my body: ke-boom, ke-boom, ke-boom. The branch was hurting me and I had to shift my weight again. More bits of bark fell down, right beside the preacher this time. A chunk landed on his face. He opened his eyes, looked straight at me and fell silent. The drums died down too, one after the other. The dancers stopped and their faces turned in my direction. Then the preacher began to ascend, rising up towards me, higher and higher, until our faces were level. The next moment I was looking up at him. We were both on the ground. There was a tremendous pain in my left arm.

I flew up and bolted down the narrow path through the vlei, heading for home. I held on to my arm to keep it still. The pain was so awful that I was crying. My clothes were torn.

“Pa’s going to kill you,” Braam said when he saw me. “Where have you been?”

Because it was Sunday, the railway doctor’s surgery was closed. Braam had to take me to hospital by bus. To the Casualty Department at Addington. When he told me where we were going, I refused, because I’d had so many bad experiences there.

When we had toothache and the cavity became too big, the sore tooth had to come out. First you cried in your bed for nights on end. Ma put cloves or brown shoe polish in the hole to keep out the cold and she made you swallow an Aspro, but when that no longer helped, Addington was the only solution. You stood in a long line. When you reached the front, the doctor gave you a shot, and then you went to the back of the queue again. When you reached the doctor for the second time, he pulled the tooth. Sometimes the line was too long, and the feeling had returned by the time you reached the front. You didn’t get another shot, no matter how you screamed.

“Not Addington, please, Braam!”

“It’s got to be Addington, or your arm won’t mend properly.”

The doctor said I was lucky I was still so young. It was just a greenstick fracture of the radius and the ulna, that was why only the forearm needed a cast. He wrapped cotton wool and wet plaster bandages round the arm without hurting me at all.

Then came the people and their questions. But their stupidity was nothing compared to Joepie’s mom’s Christian duty. That was what had forced me to tell Pa everything. And when I got to the part where the Bantu rose up in the air, Pa threw his hands in the air and asked me how many times he needed to tell me that life wasn’t a story.

But I hadn’t been telling a lie: it really had been a Bantu who had broken my arm.

Ma and the others returned a week later. And what did they bring along from the farm? Not Oupa’s rifle or his whips or the grain bag filled with raisins from the shed or the big old dining table or the riempiesbank or the old-fashioned pedal-organ. No, they returned with Ouma. Ouma Makkie.

“What happened to all Oupa and Ouma’s nice things, Ma?”

“Divided among the children,” Ma said. “I sold my share to Oom Malcolm and Tannie Toeks. What’s the use of splitting up a dining suite piece by piece, anyway? And the money’s more useful to us than a few chairs.”

“But didn’t we get anything that belonged to Oupa, Ma?” I asked.

She ran her fingers through my hair and looked deep into my eyes. “How can you ask me that, my boy? What about Ouma? We’ve got Ouma now.”

As if Ouma didn’t have other children, rich children, who bloodywell had only two or three children in their big houses. We hadn’t asked for her to come and live with us. Now I had to take her for a long walk every day because Ma was afraid she might fall or get lost or something if she walked on her own. And worse: Braam had to sleep in the passage and I had to move in with Ma and Pa.

Sometimes I woke at night and they’d be talking. I heard things I’d rather not have known about.

“I don’t know how we’re going to manage this month,” Ma said.

“Don’t worry so much, Vrou. Let’s see which way the cat jumps.”

“I’d be grateful if it was only a cat, Abram, but it’s a wolf, and he’s not jumping anywhere, he’s at the door!”

“You say the same thing every month and we always manage in the end.”

“Because I scrimp and save, that’s why. Our oldest girls are having their birthday one of these days and where’s the money for gifts? Thank God they’re the last ones this year. I’m still paying for the others’ presents.”

“They’re all old enough to understand that we don’t have money for presents, Vrou.”

“Dammit, Abram, we never give them anything.”

When Ma swore, there was trouble.

“That’s not true.”

“When they were still at school, I bought them clothes – which they needed anyway, birthday or no birthday. Sometimes you should give a person something he doesn’t need, Abram, something that comes from your heart.”

Pa was silent. So was Ma. But after a while she said: “Can’t we just keep our tithe this month?”

“It’s not ours, Ada. It belongs to the church.”

“Oh yes, the church,” Ma answered. She sounded depressed.

I wished I could tell her that next year I’d be the only one still at school; and that Mara had told me she and Rykie wouldn’t mind if they got nothing besides their silver keys for their coming of age; and that at least now that I was in high school I no longer had to take part in the younger children’s cent collection at church.

If Ma and Pa weren’t talking about money, it was about Mara and Rykie’s party. And once I was awake it was no use sticking my fingers in my ears, I could still hear what they were saying.

“But that’s what coming of age is all about, Abram, beginning to make your own decisions.”

“As long as they’re living under my roof, they’ll do as I say.”

“We danced when we were young.”

“Danced ourselves right into a wedding, yes.”

Ma was quiet for a long time.

“Has it taken you all of twenty-one years to regret it, Abram, or did you just never get round to telling me?”

“I was on my way up North. I didn’t need a wife and child to worry about.”

Silence for a while. So long that I thought they’d fallen asleep. “Now Mara and Rykie have to pay for our sins?” Ma again.

“Do you want our daughters to end up in Point Road, Vrou?”

I knew about Point Road. It was a street on the city side of the harbour, where the nightclubs were. Where you found sailors from all over the world. No decent girl went there. Everyone smoked and drank and danced. That was a word better not mentioned in Pa’s presence: dance.

“Why are you sitting here?” It was Ouma Makkie.

I didn’t answer.

“Your father?”

“Yes, Ouma.”

“Have you been naughty?”

“No, Ouma.”

“Tell me.” She sat down beside me on the rim of the bathtub. She always smelt of cloves and snuff and things. She put her hand on my knee. Her fingers were thin and knobbly and cold. “Come on, tell me.”

I shook my head. “You’ll just say I’m lying too, Ouma.”

“I won’t.”

I told her the whole story: how we had to go to church twice on a Sunday and couldn’t do anything nice and how I hadn’t been allowed to go to Oupa’s funeral and how out of boredom and pigheadedness and curiosity about the church Bantus I’d gone to the vlei and how my arm got broken.

“Did you tell it to your father just like that, child?”

“No, Ouma, not that it was a Sunday. But he already knew. Joepie’s mom told him.”

“Her Christian duty, I suppose?”

Ouma knew everything about everybody. She got up. Before she left, she said: “You wait here for a bit.”

After a while I heard her voice in the kitchen.

“Awerjam, are you going to give that child a hiding?” She never called Pa Abram. I pricked up my ears. I couldn’t hear Pa’s reply, only the droning of his voice, but I could hear that it was a long answer.

“Were you never a child, Awerjam? Didn’t you ever imagine stuff?”

Imagine stuff, she said. So Ouma didn’t believe me either.

“I don’t want to stick my nose into your affairs, I’m grateful to you for taking me in, but I’m telling you, if you give that boy a hiding today, it’ll be a sin. He saw what he saw in the vlei.”

“A kaffir rising up into the air, Ma?” Pa’s voice was suddenly loud.

“I’m telling you, he saw what he saw. The two of us, Awerjam, who don’t have his gift, mustn’t try to take it away from him. Innocence comes from above, and, Lord knows, it certainly doesn’t last.”

I heard Pa’s footsteps approaching. “Go and play, but see that you’re back for supper,” he said sternly before going down the passage to the sitting room.

I couldn’t believe my ears. I got up. Ouma was still in the kitchen. For the first time I was glad she’d come to us. As soon as my arm was better, I’d find her the best avocados in the woods. I’d cut one in half and mash it with a fork so that she wouldn’t even have to put in her teeth to eat it.

“Thanks, Ouma.”

She motioned with her hand to show that it was nothing. “Come here,” she said.

Ma had told us not to shy away when Ouma wanted to give us a hug.

“Ouma?”

“Yes, Timus, my boy?”

“What’s innocence?”

“I don’t know how to explain it.” She took out her hankie. The snuff had stained the fabric. She blew: prrrr! Then she put her arm around me again and said: “Innocence is something you recognise only when you no longer have it.”

“Then what’s the use of having it, Ouma?”

She shrugged. “I don’t know. But this I can tell you, Timus, my boy, we’ll get it back in heaven one day.”

Ouma Makkie walked out of the kitchen and past the bathroom on her way to her room.