Читать книгу Seeing People Off - Jana Beňová - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

II Café Hyena

Оглавление“Oh little fairy, if you only knew what I’ve been through…”

—Pinocchio

Elza. Rebeka and I always met just before lunch. We would go shopping together and then we took our time drinking a bottle of red wine. Meanwhile, Rebeka would cook because, unlike me, she didn’t like sandwiches, but preferred meat and sauces. All the honest, completely homemade meals, like Szegedin goulash or chicken and rice with compote moved her and reminded her of her family and eating with her mama, who had died.

Rebeka also liked to cook because wine went down well during cooking. “This is the way we live, Elza, cooking, cleaning, and drinking. Jeez, but sometimes I say to myself—we do it instead of working—but imagine those women who are at work till four and then they manage to do everything that’s taken us all day.” Rebeka lit another cigarette, took a deep drag, and for a moment quietly admired women who work. Rebeka was my best friend. We even looked like each other. There were days when people thought we were sisters. Rebeka didn’t mind it. She also had one real sister—a twin. Their relationship got sticky when the sister went around in public yelling that, in their mother’s womb, Rebeka had taken all the nourishment for herself.

Rebeka reproached her for not remembering anymore who saved her from being beaten up. “She was always baiting somebody, but didn’t know how to defend herself afterwards. We were strange twins: we won all the competitions. I was always faster at running, swimming, and climbing. My sister always won the other battles, like who could eat the most pancakes or swallow a whole muffin.”

Lately something had been bothering Rebeka. She was the only member of our Quartet who’d never worked. The ones with stipends met daily in the café so they could set the strategy. They had a system where one of them would always work and earn money while the others created. They sat around in the café, strolled around the city, studied, observed, fought for their lives.

The fourth, meanwhile, provided the stipend. Just as other artists get them from: the Santa Maddalena Foundation in Tuscany, the Instituto Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon, the Fulbright Foundation in the USA, or the Countess Thurn-Taxis in Duino.

The Trinity Foundation had its headquarters at the Café Hyena, which the patrons renamed Café Vienna. It was a spacious café patronized mostly by foreigners and rich people. Here they considered the Trinity to be students. They were always shivering with cold, not dressed heavily enough, warming their hands on the hot mugs, mixing all kinds of alcohol, and continually writing something or making notes in books or magazines. Sometimes they would close a book loudly, put their hand on its spine, and look off into the distance with a sigh. So the other guests knew that they had just gotten to an idea in the text that had suddenly completely changed their life. Sometimes they stood up and nervously walked around the café. Tapping their fingers impatiently on their lips. Creativity broadcast live.

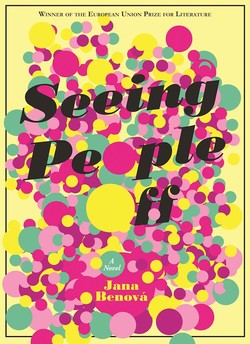

Today at the Hyena, Elza is reading aloud from Seeing People Off. The first ten pages. The air grows tense from the vulgar words and a pair of older women and two families with children rise from a table covered with desserts and leave. At the end, no one applauds. A lady in violet comes over to Elza. “I don’t easily go up to people and give them my opinion, but I have to tell you that Petržalka isn’t like that. I don’t know where you live—there are weirdoes everywhere, but this? Not like that! And I guarantee you that if you leave the beginning like that no one will buy your book. I guarantee you. And I’m not even a teacher.”

When the Quartet discussed something, its members shouted over each other, rising out of their chairs with faces burning. Sometimes they celebrated here. On pay day, when the stipend came for the next month. Then they inordinately drank, ate, and argued. They filled the whole café with their yelling.

“Don’t talk shit to me!” shouted Rebeka at Elza. They were arguing about the character of Cowboy in the Lynch film Mulholland Drive. For Elza it was a negative character and for Rebeka positive. He reminded Elza of a secret police agent, Rebeka of an alchemist. During their argument, Elza’s friend’s face changed from its original Rebeka-the-little-sheep, Rebeka-the-lamb, from doe-eyed-dog-Rebeka to Rebeka-the-wolf, -lion, -tiger, -dragon, and finally it glowed pure, blinding, motionless gold. And golden-mouthed-Rebeka shouted: “So shut your trap for a second, for God’s sake, shut up, Elza!”

“You’re not arguing with me, you’re arguing with the wine,” Elza laughed.

“I think it’s time. She should start earning,” said Elfman.

“Her? She’s so frail,” doubted Elza.

“Oh please, don’t talk to me like some bisexual,” said Ian, annoyed.

Rebeka. Money—again we need money. We can’t live forever like this: with no money. Now it’s my turn—I’ll try to start earning. And we’ll see. I’ll find a job, start a business, I’ll go to work, earn money, money, money, I’ll be an employee, I’ll settle in, fit in, straighten out my life, mature, become independent, secure.

I can do anything except teach. Teachers have it the worst. Even when they aren’t at school, they hear a classroom full of kids everywhere: voices, chairs scraping, pencil case zippers, a compass being stabbed into someone’s back.

In the deserted woods, the voices of children on a school trip come to them. They move with them, melding with the burbling of the brook. “Why did they take the kids on a trip to such a deep deserted forest? And why now, at midnight, on New Year’s Eve?” the teachers ask themselves in the desolate wood. “And if we’re asking this, then what for God’s sake are the children asking themselves?”

Rebeka’s grandmother was a teacher once. She talked about some of her students. For example, about a boy who called everyone a loser. His father was a musician who played Dixieland and the kids made fun of him, saying that he played dicksilant. Or about a woodworking teacher who cut off his finger during class and the kids saw him off to the hospital, laughing all the way. He carried his finger in a bucket full of ice. The doctors in the hospital poured it down the toilet and flushed.

Elza took care of the stipends for the Trinity last time. She worked under various pseudonyms in several competing daily newspapers. They were usually influential papers with national coverage and a common management center.

The first place she worked was in television. Under the pseudonym Kaufman, she was public relations manager for a reality show, which took place in the Dachau concentration camp. The blue group lived like imprisoned Jews, and the red group played the role of guards. There were great hopes for the show, especially financial.

The office reminded her of a scouts’ camp or a kids’ school classroom. The people, who worked crowded one on top of the other, ate at their desks, cursed, worked, and commented out loud on everything they were doing. They ran around and played their games.

At work, some tried to attach themselves to others. They looked for protection. Like those lonely beings who cried during the whole time at camp, missing their parents. “I’m never leaving home again,” they said to themselves. And they gathered in pathetic, tight groups. A couple of children crying in their own little circle. The thing that had annoyed her most was the evening sessions where everyone sat around the fire and sang. One song after the other.

Little Elza always sat hidden in the back row, but just in case, she opened her mouth as if she were singing. She didn’t make a sound. But from her moving lips you could read: “We are the children of a freeeee country.”

She did the same now—at work. She moved her lips.

Around her, workers ran about hectically. They cursed, quickly catching their breath, were always behind, hissed and sizzled. They didn’t sleep, didn’t eat. They didn’t eat, didn’t sleep—just whistled while they worked. They were heroes—neurotics running in circles. Their charm lay in their eternal dissatisfaction. (“God, why can’t they let me finish one thing? Not now, I can’t. I don’t have time. I have work to do, I have to make myself a cappuccino!”)

All the women at work called each other by the nickname “hon” and white poisonous spit collected in the corners of their mouths.

Red dots shown in the corner of every eye. Sometimes they switched languages. To a special women’s language, Láadan. After elasháana and husháana, osháana—a word for menstruation—and ásháana, meaning to menstruate joyfully, were the next words which were supposed to guarantee women in Slovakia equality of rights.1

The concentration camp reality show was such a failure that it bankrupted the TV station. The whole network.

At a meeting, Elza’s supervisor shouted that the problem was that viewers weren’t engaged enough. “The war ended a long time ago, today we can’t get any more mileage out of it.”

“Unless we unleashed the war again,” commented one of the special effects guys. The director threw that idea out. He used the argument that everyone would lose money if they did that. “During wartime, money loses value, the world operates on rationing coupons.”

In January, days came when Elza felt like her inner organs had disappeared from her body. Her breathing tubes ended just below the neck. Then she ate and drank. And she was surprised that those pieces of bread, tomatoes, and cookies disappearing into her mouth didn’t immediately show up under her feet. Her breathing was shallow. It moved between her nose and mouth. Forget about asanas!

She remembered her grandfather’s joke about Jánošík2. They hung Jánošík up by his rib, but he just kept hanging and wouldn’t die. He asked the petty officer if he could have a cigarette. The officer said, okay, if it’s your last wish… Jánošík went to the corner store for cigarettes and had a smoke. But the smoke came out of his lungs through the hole under his rib. He didn’t get that true pleasure from smoking. He gave up, tapped the ashes from the butt, and jumped back up onto the hook.

Youth camp for some people started again in old age. Elza’s aunt lived in an old age home in Budapest. On Margaret Island. Elza and her mother visited her once a month. She always wore gloves and smelled of old furniture.

In January, the old woman (gloves and all) jumped out the window. She committed suicide because she couldn’t be in the bathroom for as long as she would have liked. She couldn’t spend as long in the shower or in front of the mirror as she needed. There were always other people waiting at the door. Someone was always breathing down her neck. Knocking.

The old age home was a continuation of youth camp. A common bathroom, too much singing, scheduled meals that someone else chose for you, here and there a party.

On the road home from Budapest a truck blocked their view the whole way. On the back it had a sign for Italy framed by tomatoes and bottles of wine. Elza thought of the sea, Pompeii, and Lagrima Christi wine. She longed for big cities—Lisbon, Rome, Amsterdam, and London. She associated them with a feeling of freedom and abundance.

In a foreign city, she and Ian always made love twice. In the morning and before going to sleep. They formed a pair that had to continually affirm itself—convince itself of its own homogeneity. Its functionality. It grew two new heads with clean tongues. They used them to lick the new country.

No one understood them, their speech became secret and romantic. They thought it up just for themselves. No one ruined it for them or expanded the borders of their world with seeming comprehensibility.

World events ceased to exist. Holding their breath, they scanned the headlines of the local newspaper, which they didn’t understand. To Elza, foreign cities felt free because she had never worked there. She didn’t know the mayors, the city neighborhoods, the offices, the scandals. She didn’t have to chase anyone down in them, or call around. She had no contacts.

Elza. Bratislava. A city that grips you in its clutches. On the way from work to Ian and from Ian to work. Tied up in the rhythm of your own steps. The rhythm of the city. The rhythm of lovemaking, work, parties, earning and spending, gaining and losing. Are you making money? Combining ingredients? Time, men, and money? City, wine, song, and work? Friends, love, and idiots. Pancakes! The Bratislava alchemist.

Bratislava. A city that forces you to pounce on something, just as it has pounced on you.

In the newsroom. “What do you actually do, Elza, in reality? Are you writing a novel? Aha… You’re lucky, I would do the same. If I had the time. If only you knew what I’ve been through. What a book that would be!” The Editor-in-Chief sighed and poured himself some white wine. Oh, little fairy, if only you knew what I’ve been through… He sat down on her desk, put his hands on his hips, and looked into her eyes.

“How are you doing—have you found anything out?”

“You know, I really don’t know now, what’s going on. What’s true in this case. I don’t have a way to confirm, but I’m trying— I’m calling around, asking, waiting.”

Under her boss’s blue-eyed gaze, Elza was flooded with heat. A blue flame burned directly in her face. She thought she could hold on and kept talking. But at one point she felt that if she didn’t take off her turtleneck, she would burn up, explode, melt on the surface.

“At the beginning it seemed clear. But confusing information keeps coming in. We shouldn’t panic,” she continued, trying to pull her turtleneck over her head. She thought she could do it in one fell swoop. But her sweater got stuck just above her head and she was wedged inside it. “I’m not sure I’m going to make it by the deadline. But tomorrow it would already be old news. I have to find out somehow. I’m looking for contacts,” explained Elza with her head under her sweater. In the dark she felt like she wasn’t fighting with the sweater, but with her own skin. That by mistake, she’d pulled the skin off her back right over her head. “Sorry it’s like this now,” she said, thrashing around. Then her boss held her undershirt down with one hand and with the other ripped the turtleneck off her. He saved her life. And the skin on her back would grow back quickly anyway. Of that she was sure. She didn’t even have to call anyone.

Elza. I’ve had problems being wedged in since childhood. Whenever I washed my hair in the sink of a cheap hotel, I usually got my head caught between the faucet and the sink basin. The drain was plugged and the water still running and it rose up to my nose and mouth.

On the way to school, in the back of the tram by the window, I leaned against the railing, which followed the wall of the tram car at about a 10-centimeter distance. While I was talking, I stuck my arm in between. When I wanted to get off, I realized that I couldn’t pull my arm out. The elbow was too wide. I was wedged in.

“Don’t panic. Don’t panic, said a group of Polish tourists who were riding with me. The driver closed the door in people’s faces and laughed. The Polish people prayed quietly. With every movement, my elbow grew bigger.

The moment they sent Elza to write about the opening of the 3D cinema, she thought of Ian. A few years earlier, he would have been the first to go there, so that his eyes would be opened. A 3D cinema has a three-dimensional screen. The trick is based on shifting the vision of one eye in relation to the other. Since 1999, Ian has only seen out of his right eye. But Elza knew that even if he couldn’t be amongst the first viewers, he would surely catch the news in time that this cinema—useless for him—was opening. Because since childhood, Ian had been buying reams of newspapers and magazines. He looked forward to them with unbridled excitement and flipped through them endlessly. Columns and towers of them piled up in his room. He couldn’t part with them. In every old magazine it seemed to him there was something extremely interesting that warranted keeping, and he didn’t want to give or throw it away. “It’s all information,” he said to Elza. “I might need them one day.”

And Elza admits that Ian truly did always know a ton of interesting facts. While she roasted a chicken, he talked to her about the newest theory of the origin of the universe, about the problems cloned sheep suffer from, about the main character’s fate in the documentary film Nanook or about a quite new Irish band that had suddenly sold more albums at home than U2.

And while she’s taking the chicken out of the oven, Ian says: “And they’re opening a 3D cinema here tomorrow. But they definitely won’t show any high-quality films. Just some circus attractions, don’t you think?” Ian asked and answered himself.

Elza. Ian is mine. Ours. We kiss as if it were the first time. Like the first couple who ever kissed. We’re a being with one body, two tongues, and three eyes.

At the 3D cinema they were showing a film about dinosaurs. After it finished, Elza never went back to work. Observers considered it to be a stylish end to a career.

In two days she was surprised by a café full of colleagues.

They came to Café Hyena to say good-bye.

“Shoot,” Elza wanted to say, shocked.

“Shit,” she said instead, unconsciously.

1Láadan is a language created in 1982 by Suzette Haden Elgin intended to better express women, whose viewpoints were felt to be shortchanged in many Western languages compared with those of men.

2Jánošík is a character from a Slovak legend similar to Robin Hood.