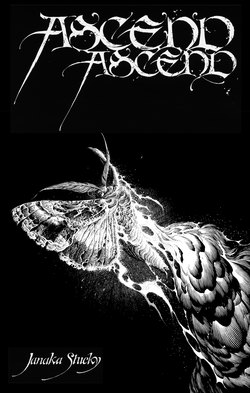

Читать книгу Ascend Ascend - Janaka Stucky - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOREWORD

ОглавлениеI was standing on a shaded slope of Minnesota woodland the first time I encountered this mystic feast of a poem. Coming from above was the frenzied cry of birds, fighting or fornicating I couldn’t tell which. Beneath me was the now-horizontal trunk of a very tall tree, which had cracked over in a recent storm. There was a stream murmuring before me, and behind me a glimpse of one of the many lakeside mansions that seem to loom out of the wilderness more and more often with each passing year. It seemed a very apt spot to get lost in Janaka Stucky’s skein of wonder-words about searching for transcendence in the Anthropocene, or, as he puts it “…responding / With purity to the collapsing / Sigh of the world.” Incantatory and mesmeric, like all of his poetry, Ascend Ascend is a work that begs to be read out loud. And so that is what I did. Pretty soon, I was sighing, too.

I started on my feet, trying to channel the spirit of one of Stucky’s shamanic recitations (which if you haven’t witnessed yet yourself in person, you must remedy posthaste). As I read, I imagined I was calling up and out, to the birds, to the leaves, to whatever lesser gods of the woods were listening that day. At points my voice would tire, or my knee would give a twinge, and I would sit down on the trunk for a bit, and read more quietly, thinking of bones and stones and roots. Then I’d stand again and read loudly again, shifting from foot to foot. So it went for over an hour, back and forth, back and forth. It struck me as a sort of davening, this up and down motion, the sway. And I thought about how rapturous poetry like Stucky’s is so very similar to prayer, for both are embodied entities as much as they are spirit-stuff. They are offerings from the flesh to invisible forces. Tributes from a Me to a Thou. Language is a bridge between realms, then.

And in this work, Stucky proves once again to be a particularly remarkable architect. For, despite its lofty title, his is an intricate and multi-directional construction——as grimy as it is glittering. He shows us that the path of ascension is never a straight line, but rather a circuit of elemental processes we cycle through. We burrow, we fly, we drown, and we burn. We fall before we rise. And so it goes, these great deaths and merciful (re)births happening within and around us every moment of our lives.

He also reminds us that the way to reach the ethereal is by going through the material, with all of its sensual terrors. Where Whitman sang the body electric, Stucky sings “the body exquisite,” and with this ode to mud and blood and fungus of all forms, we know he means his own and the heavenly body of Earth, both. These are dwelling places, and as such they are spaces of sublime pleasure and pain——or as Ginsberg wrote, “Holy! Ours! bodies! suffering! magnanimity!” According to Stucky, these bodies house landscapes of diamonds and excrement, of “the numinous / Spell of flowers” and “a brilliant storm of intestines.” These bodies are dark and rotting and full of sweet, holy fire. These bodies are where we live, and what we’ll leave behind.

These sites are sacred not only in their physicality, however. Our homes hold something more. Some might call it soul, or quintessence, or maybe even magic. In Stucky’s telling, every layer of the universe is laced with divinity, as is every moment: “There is a precise instant when the world / Is marvelous / Now / Is its name.” In his occult topography, there are seven heavens amongst the soil, and the bottom of the sea is equally stuffed with angels and crustaceans. Here, the seraphic palaces of Merkabah literature aren’t only in the celestial sphere, but are mapped onto this very planet, rendering it a sort of supernal-terrestrial palimpsest. This work is an exploration of immanence, as much as it is an attempt to reach beyond.

And so, Ascend Ascend is a poem about beingness. It reflects the perpetual ricochet between poles that all organic creatures experience, but which human consciousness renders all the more gorgeous, and all the more ghastly. We’re led through earth, air, water, and fire. We shimmy up the Tree of Life, get caught in its labyrinth of limbs, and tumble back down again. Stucky’s lines show us that the Kabbalistic sefirot are footholds that can launch us into higher consciousness, or trip us up entirely, and that so often the greatest discoveries occur along the route from one position to the next. It’s a treacherous ordeal, this eternal transmutation from one condition to another. Sacred and profane; spiritual and corporeal; exhilarated and excruciated; As Above, So Below: the tension between these states constantly threatens to obliterate us. But Stucky’s piece asks the question: what if obliteration is the point?

For who hasn’t longed, on some fleeting occasions at least, to let go of oneself entirely? To merge with the grand Whatever It Is that makes this world so difficult and bright? Certainly the ecstatic poets that Stucky is a successor of all express this very sentiment. One can’t help but think of the “ancestors of ancestors speaking with centuries / Upon centuries of mouths” with whom he is in dialogue: Hafiz, Blake, Yeats, Doolittle, and di Prima, to name but a few. So often, their poems are about surrendering to some sanctified source, and then melting away into it. Rumi wrote “Let the caller and the called disappear; be lost in the Call.” And per Kabir: “I’ll keep uttering / The name / And lose myself / In it.”

But rather than give over to its thrall, poets instead take on the impossible task of trying to pin the wings of the ineffable with words. In doing so, they grant the reader a bit of flight as well. Ascend Ascend touches upon this paradox, for it is also a poem about language. Alphabets, intonations, and supernatural syllables are referenced throughout the work. Stucky is engaging in “adamic / Choreography,” putting names to things with the elated mania of first man. I thought about this, too, as I finished reading it to the woods, and then found myself looking around stupefied. Adam’s own name comes from adamah, meaning “earth,” and in stringing the world with words, he created it anew, before being swallowed up by it once more.