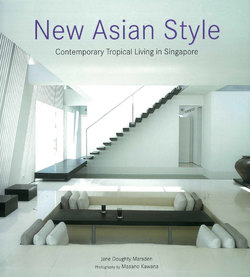

Читать книгу New Asian Style - Jane Doughty Marsden - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEastern Ideals, Global Directions

"LIVING in Asia is a little bit about chaos," says architect Chan Soo Khian, challenging notions that associate serenity with the East. As lifestyles become more urban and cities more congested (Bangkok's police are delivering up to 25 babies a day in the backs of gridlocked cars, while Singaporeans have to bid for the right to even own a car), people-and their homes-are looking inward.

"Zen is here to stay," says Singapore-based interior designer Stefanie Hauger, "in the sense of a desire for a holistic lifestyle in which the home is seen as a sanctuary, with Asia having the added bonus of being surrounded by art and artefacts that stem from the very source of this new approach to living." Across the globe, from Donald Trump to Richard Branson, Prince Charles to Rob Lowe, people are using feng shui principles of placement in their homes, while the revival of the 1960s movements of minimalism and modernism can be seen as another reaction to postmodern excess. The role of the home as a tranquil refuge from the outside world has never been more important.

Just how this is being done in Asia varies. A new generation of architects (many of whom are venturing into interior design) is revealing that what is Asian extends beyond artefacts-or a lack thereof-to spatial and spiritual qualities. The way one enters a house, the hierachy of privacy, ambiguous spaces created by transitory screens and surfaces between the interior and exterior, the presence of water, the open plan, a courtyard, shadows animating a blank wall-all are a celebration of simple beauty or what the Japanese call wabi sabi. "It's less a recognizable look and more an attitude of how we look at space and design," says Singapore-born Yale graduate Soo Khian.

This attitude informs New Asian Style, whether the look is zen minimalist, contemporary ethnic, tropical modern, retro and recycled, or a fusion of two or more of these general trends, as it is most often these days. It is becoming increasingly hard to apply labels, as the examples in this book show. Thus, the pioneers of the Balinese aesthetic for residences in Southeast Asia more than a decade ago-architects like Kerry Hill and Ernesto Bedmar-are now transcending traditional archetypes in an unselfconscious contemporary tropicalism inspired in part by the work of Sri Lanka's most famous architect Geoffrey Bawa.

"We are now referencing and reinterpreting past traditions through suggestion and association rather than replication," notes Hill, whose Singapore-based company KHA designed the Datai resort in Malaysia and Amanresort's Amanusa in Bali, as well as numerous private residences for Asia's elite. His partner, Justin Hill, asserts that "decoration has had its day and we are even moving away from traditional materials". Bedmar is also experimenting with materials such as aluminium and steel as alternatives to the increasingly rare well-seasoned timber to "achieve, in a very simple way, the same poetry, homeliness and romance as traditional architecture".

While simplicity and zen 'holism' continue to be the trend (from Italian couturier Giorgio Armani's homeware collection to Singapore furniture designer Tay Hiang Liang), for most people extreme minimalism has proven too austere, impractical and downright confusing (yes, even to Asians, many of whom equate it, as one home owner says, with "an uncomfortable Italian sofa"). Regional interior designers such as Hauger and Marlaine Collins are predicting a return to comfort and an emphasis on softer interiors; international talents such as London homeware designer and Designers Guild consultant William Yeoward are already producing luxurious fabric collections inspired by the East.

Sharing space with the pool, the tropical modern house of Claire Chiang and K.P. Ho is supported by concrete pillars treated to resemble granite, Parts of the second floor are suspended over water, blurring boundaries and enhancing the resort feel.

Despite the trend towards hermetically-sealed, high-rise living in space-starved urban areas in Asia-which is fostering "shiny glass boxes without a trace of soul or context", according to tropical modern architect Guz Wilkinson, there is a growing backlash against what Bali-based landscape gardener Made Wijaya calls "what passes for New Asia-nouveau, neo-New York or just ugly". Home owners and industry professionals such as Wijaya are taking up Indian designer Rajiv Sety's warning: "Everyone's so busy going global, they've forgotten about local!"

Whether it is the rich detail of mother-of-pearl tiles from Suluwesi or 1950s art-deco furniture crafted in Singapore, sophisticated Asians are realizing the potential of local cultural sources and design elements to impart magical moods in contemporary settings. So are their Western counterparts; David Copperfield's New York apartment conjures up a languid colonial lifestyle with poolside items such as Javanese planter's chairs; John Cougar Mellancamp sleeps in an antique Burmese teak four-poster; more contemporary Asian home accessories are being commissioned by Donna Karan, Karl Lagerfeld and Joseph from designers like Thailand's Ou Baholyodhin. Singapore-based interior designer Ed Poole, whose projects in Southeast Asia include the communist-chic House of Mao restaurants, has coined the term "urban tropic" for "the new Asian look in which modern furniture and accessories-everything from place mats to ashtrays-are being produced using indigenous materials such as coconut wood in places like Chiang Mai and Bali".

Juxtaposition is the key. Singaporean architects and interior designers Mink Tan, Sim Chen-Min and Sim Boon Yang are developing an 'ethno-modern' approach by placing focal areas of exotic details against clean, contemporary backdrops. "We want to avoid the dogmatic distinction of modern versus Asian vernacular," says Sim Chen-Min. This sentiment is echoed in the West by authorities as diverse as US-based fashion designer Vivienne Tan, whose China Chic takes a highly personal and provocative look at using cultural details (cheongsams to Qing desks) as counterpoints in Occidental settings, to UK-based interior designer Kelly Hoppen, whose East Meets West style is seen everywhere from first-class airline cabins to the homes of celebrities. As Hong Kong entrepreneur and designer of the elite China Clubs in Asia, David Tang, notes: "If you want to do a Chinese interior these days, it has to be a bit Western."

Bathroom bliss. In Judy and Morgan McGrath's tropical modern home, a painting by Indonesian artist Sukamto rests on an easel by the free-standing jacuzzi tub. The smoothness of the latter is a delightful contrast to the textured travertine used for the floor and shower area.

Collector's corner. Antiques such as a 19th-century Burmese betelnut box (on floor at left), a 19th-century Thai repousse silver bowl (on a Thai reproduction rain drum) and a Tibetan medallion rug create an exotic living space for Catherine Lajeunesse. Behind the Filipino rattan sofa (with Princess & the Pea cushions) is a Thai temple drum.

While dining under red silk lanterns and stainless-steel window bracing is not everyone's cup of cha, the idea of being unapologetic about the past-communist, colonial or kampong-is another facet of embracing what is local. Kerry Hill calls this 'authenticity': "It has to do with the genuineness of origins, a sense of belonging. It is felt as much as it is seen and evolves through intuition." However, in this age of mass communication and travel, what is local and what is universal is becoming increasingly intermixed, as Hill is the first to point out.

New Asian Style is somewhere in between local and universal, modern and ancient, chaos and calm. Nowhere in Southeast Asia is this more apparent than the former British colony of Singapore, where all the homes in this book were photographed. The vast majority of the three-million-strong population of this young city state which separated from Malaysia in 1965 lives in high-rise apartments and is comparatively well-educated (increasingly outside of Asia) and well-travelled. Moreover, as in the West, these 'New Asians' are increasingly likely to be living as single occupants or childless couples as they are in nuclear or extended families.

Such broad brushstrokes characterize the home owners and house occupants in this book who are "as distinguished by their multiplicity" as their homes, to paraphrase Singapore-based architect and author Robert Powell's definition of 'New Asian'. They are just as likely to own a second home in Bali as in London; they shop in Bandung, Bangkok and Brisbane; they tend to design at least some of their own furnishings; and some of them are not even of Asian ethnicity.

An attitude more than a given look, New Asian Style is above all about invention, experimentation and individuality, qualities which are unrestricted to geographic or racial boundaries. The urge to personalize one's home environment has never been so strong. As Donna Warner, editor of Metropolitan Home, says: "Homes are about happiness, not about being right."

Elegant Chinese furniture such as this late Qing Dynasty blackwood reading chair characterizes this contemporary Asian interior by Stefanie Hauger and Arabella Richardson, in a shophouse renovation by Chan Soo Khian.