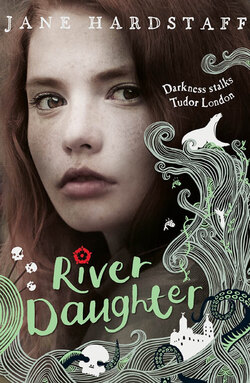

Читать книгу River Daughter - Jane Hardstaff - Страница 10

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

Boat Thief

It was unthinkable.

Wasn’t it?

Moss lay back on her pallet staring at the ceiling.

Even if she took Salter’s boat, she’d never been further than a few miles down river. Salter had told her, though, that if you went far enough the gentle chalk river gathered speed until it met the wide path of the Thames. Flowing past fields and towns to London. There it became the murky torrent she knew, raging through the arches of London Bridge and all the way out to the sea.

But why did the Witch want her to go there? What did she want from Moss?

She rolled over and kicked off her blanket. She couldn’t breathe in here.

What if she didn’t go? What if she stayed here? If she never went near a river again, the Witch couldn’t touch her.

Freedom . . . isn’t that what you’ve always wanted?

This past year and a half here in the village, with Pa and Salter, Moss had experienced more freedom than she’d ever dreamt was possible. And now she thought about it, the river was a huge part of her new life. Salter fished it, she swam in it. To run from the Riverwitch now would mean giving all that up.

Softly she slipped from her pallet and tweaked the curtain. The forge was heavy with Pa’s deep sleep. No noise from Salter. In those early days, when Salter had let her stay in his cosy shack, Moss had discovered he was a light sleeper, always half an eye open in case of trouble. But since coming to live in the forge he’d slept like a boy who’d been turned to stone.

Moss pulled on her dress and boots. She patted her pocket. The little bird was there. Then she laid out her blanket. On it she placed a knife, a wooden mug, half a loaf of bread, some cheese and her tinderbox. Reaching under her pallet, she pulled out her winter shawl, given to her by Mrs Bailey last year when the frost came. If nothing else, she could sell it to buy food. Folding the blanket over these few possessions, she tied the ends together and slung it over her back.

Even in boots, her steps were soft on the earth floor. She knew Pa would not wake. There could be no goodbye of course, stealing away in the middle of the night. But at least she could let him know she was coming back. As quietly as she could, she opened a shutter and plucked a sprig of red-berried hawthorn from the bush that grew outside their window. Tiptoeing to the table, she removed the hazel from the jug and replaced it with the hawthorn. Then she tweaked the curtain to Pa’s pallet and took a last look at her sleeping father.

The great bear-frame of his body rose and fell. A frown creased his face and Moss wondered where he went in his dreams. She was sorry that he’d wake up and find her gone. But Salter was there to help in the forge and pick the skirrets, and in any case, she hoped she would return soon enough.

Outside, the fields were pink-orange in the glow of the harvest moon. Moss heaved her bundle over the fence and clambered after it. The grass, damp with night dew, brushed her legs. She crossed the fields quickly and then she was at the river.

She didn’t feel good about taking Salter’s boat. He’d made it himself from pieces of old timber he’d found on the Baileys’ farm. It lay upturned on the bank. She heaved it over, half-expecting it to cry out for its master, but the only sound was the slap of wood against water as she slid it into the river. She tethered it to a tree stump and threw her bundle in.

‘Goin somewhere?’

‘Oh!’ Moss jerked round. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘I could ask you the same thing, Leatherboots. Sneakin off in the night. Takin me boat and whatever else you got in that bundle.’

‘It’s just food and a few things for the journey.’

‘Journey, eh? Goin far?’

‘Down the river.’ There was no point lying. Though she didn’t have to tell him the whole truth.

‘Is that right? All by yerself ? This river ain’t no gentle row. You may be able to manage up here, but downriver it’ll whip along fast and furious.’

‘I know. You don’t have to tell me.’

‘Then what’s this all about, shore girl? And why creep off in the night, not a word to me nor yer Pa?’

‘You wouldn’t understand.’

‘Try me.’

‘I don’t even understand it myself. It’s just a feeling.’

‘Well I got a feelin. A bad feelin. You been funny ever since yesterday in the river. And whatever it is that you ain’t tellin me, it’s makin you do a stupid thing.’

‘It’s not stupid. And anyway, even if it was, you’re not my keeper. I can do what I like, Salter. Go where I like.’

Salter considered this. ‘All right then.’ He threw his leather bag into the boat.

‘What are you doing?’

‘Comin with you.’

‘You are not.’

‘Try and stop me. Anyway, that’s my boat yer in.’

‘Fine. Suit yourself.’

She watched him push off from the bank and hop on board. They wobbled into the current. Moss took the oars and began to row. Salter sat back.

‘Cheer up, Leatherboots! It’ll be good to see that old city again.’

‘Who said anything about London?’

‘Call it a feelin.’

‘Good or bad?’

Salter looked at Moss. She waited for the crinkle in his eyes, but none came.

‘Too early to say,’ he said.