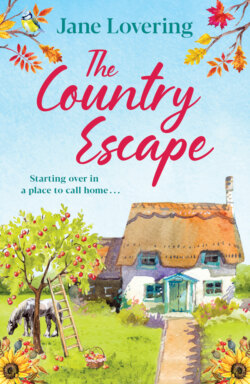

Читать книгу The Country Escape - Jane Lovering - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5

ОглавлениеA couple of weeks went past. I held off doing any painting, but did manage to unpack some of the boxes that had travelled with us from London, the contents of which looked horribly urban in this tiny, thick-walled space.

I tried to arrange the asymmetrically striped black and white cushions on the sofa, so that they looked comfortable, rather than like the ‘room accents’ they were bought to be. If this room had an accent, I mused, it would be rural Dorset, not the sharp and edgy that we’d gone for in the two floors of the five-storied old Georgian town house that had provided our accommodation in London. There, bare floors and exposed woodwork was a statement that said, ‘I can afford to cover all this area in lavish carpeting and internal walling, but I am carefully choosing not to.’ In the cottage, bare floors were necessary until we got the damp under control and exposed woodwork was what was left where the paint had flaked off. It was very different. Two of the brambles from the orchard had climbed in through the pantry window and, despite my regularly cutting them off with the scissors, kept infiltrating the shelving, and every time I opened the door it was like The Day of the Triffids. I couldn’t wait for autumn to really get under way and stop the relentless growth.

Patrick was still in the orchard. Apart from one brief text from Gabriel Hunter checking up on him and telling me that the cottage was ‘a possible’ for location work, I’d not heard from him. Poppy continued to hate her new school, doing homework intermittently and, according to the notes in her planner, not really applying herself to any of the subjects she’d chosen to study.

‘I chose last year!’ My accusations that she wasn’t working hard enough were not warmly received. ‘Pasty Greggs was really cool! Now I’ve got Miss Thompson for music and she makes us listen to Beethoven! That’s, like, against my human rights and stuff.’

Poppy had no idea what she wanted to do when she left school. Apart from being a YouTube star, or a vlogger/influencer, there weren’t many careers that interested her, and her monied father’s attitude to life being ‘you can just float around doing what interests you, making little bits here and there and being largely supported by your family’ really wasn’t going to take her very far, unless she was going to specialise in following bands across the country and take A levels in ‘interesting hair colours’.

‘Got an A in French though,’ she pointed out, thrusting a pile of notes under my nose. ‘So, there’s that.’

‘You’ve been bilingual since you could talk – it’s hardly an achievement!’

Poppy sighed. ‘Don’t take it out on me that you’re stuck here all day. I didn’t ask to move to the Depths of Despair, did I? We could have still been in London, you’d have your teaching and I’d be getting all As and still going out with Damien!’

The door refused to slam. It was slightly too big for the frame and had to be dragged across the floor in order to close, but the slam was implicit. ‘And it’s not hormones!’ was her passing shot as she stomped upstairs to a more satisfactorily slam of her bedroom door. ‘You’ve ruined my life!’

I stood under the bare bulb in the living room and took several deep breaths. I’d already had a lengthy phone conversation with a couple of old friends back in town, who had only managed a small amount of sympathy with me; their jobs were over-pressured and fraught and they clearly imagined life in the countryside to be very different from the reality. I really couldn’t ring them back to complain about my teenage daughter. My best friend, Lottie, was struggling with nursery school placements for her small son and juggling her teaching job on top, Arlene was dealing with a sick mother and resentful husband and Basia was on stress leave and contemplating a return to Poland. Here I stood amid the silence of my bought-and-paid-for cottage – a wailing daughter didn’t really score that highly in the tension stakes.

But I wanted to talk to somebody. Apart from some exchanges about the weather in the supermarket in Bridport, and the encounter with Gabriel, I’d barely spoken to a soul since we moved in. Patrick was not a great conversationalist, and had nudged me hard enough to spill my tea when I’d sat on the van steps and tried to interest him in the trials and tribulations of life. So, when my phone rang, I grabbed it with an out-of-proportion gratitude.

‘Ah, there you are.’

The gratitude dissipated quickly in the face of my mother’s disapproving tone.

‘Hello, Ma.’ A long pause. ‘How are you?’

‘I am well.’ Another pause. ‘And you? Are you safely moved to… Dorset?’ The slight gap told me that she’d had to look up my new location, probably in her little red book. ‘I’m just telephoning to tell you that I’m off to Sydney next week, probably won’t be back until Christmas. You know, in case you needed me.’

I perched on the arm of the sofa, the velvety fabric catching at my jeans like tiny fists. ‘Well, thank you for letting me know. Have a good time with Aunt Christie, won’t you?’

These conversations with my mother were so underrun with currents of tension that they practically stood up on their own. Our relationship was cool, practical, distant; she sent presents for Poppy and saw her once or twice a year, always let me know of her own whereabouts. In return, I sent flowers for her birthday and Mothers’ Day, a personalised gift for Christmas, and the approved condolence cards when one of her circle died. All our interactions were very much based in the present; we had erased our past and it was never spoken of.

‘I will. Goodbye, Katherine.’

And that was it.

Other women, I knew, could have told their mothers about the isolation, the loneliness, the fear of failure. The cold dampness at night, when I lay awake listening to the distant sea or the rain against the windows, worrying about never working again at the grand old age of thirty-four. About my ultimately unsuccessful marriage, the lack of local jobs, the crumbliness of the cottage and the fourteen-plus hands of piebald squatter in the orchard. But not me. And the gap between the relationship I wanted with my mother and the one I had, and the currently strained relationship I had with my daughter, made me sit for longer than I should have done under that bare, swinging bulb.

I was eventually brought out of my dark thoughts by the fact that my phone was buzzing an incoming text against the palm of my hand. Maybe my mother had thought of something to add? I was about to lay it down without looking, when I saw the name on the screen.

G Hunter:

Sorry I’ve not been in touch. We’ve had a meeting and I’d like another chat about using your place as a location. Any chance we could meet up? There’s a really nice pub just outside Steepleton if you’re free this evening…

I didn’t even think twice. I texted back.

What time and what’s the name of the pub?

PS Patrick is fine, but needs to move.

G Hunter:

It’s The Grapes, up on the Bridport road. Eight o clock?

We can talk about Patrick too.

I’d been hoping for plans to move the pony, even the promise of an immediate single-horse trailer on the road. As it was, Patrick was running out of grazing in the orchard, and some recent rain had caused him to form a mud trail from the back of the field to the kitchen door, where he often stood disconcertingly staring in at me through the rattling glazing.

‘I’m going out for a while later,’ I called up the stairs, although Poppy probably had her earphones in and music blasting from her phone.

There was a moment of quiet and then her door opened a crack. ‘What?’

I repeated myself. It wasn’t an unusual experience. ‘I’m going to meet up with the man who might use the cottage for a location.’ Why I had to justify myself, I wasn’t sure.

‘Oh. Oh! Is this the bloke that knows Davin? Only, this boy on my bus, Rory, he’s in Year Twelve, he’s a bit of an idiot with a stupid haircut but he talks to me so there’s that, well, he says his mum runs this café, right, and he knows Davin, and his mum’s boyfriend, who I think is called Neil but that might be this other guy, he does sound on the new series! Probably a load of bollocks and he’s just trying to impress me.’

Well, at least she was still talking to me. I wasn’t sure if the stream of consciousness was better than the grunty silences; it took more processing but if you could winnow the sense out of it, there was often a giveaway or two to be gleaned. In this case, the name Rory. It sounded as though Poppy might have made a friend.

‘Yes, we’re going to have a chat about the cottage. And Patrick.’

‘You can’t send Patrick away, Mum. You can’t.’ The door closed again. It didn’t slam, but that was probably only due to the amount of stuff on the floor preventing it. The bulb swung as Poppy walked across the floor above, throwing weird shadows across the room.

I still hadn’t quite got used to the darkness out here; the way it came creeping in so early, like a lodger returning before the landlady had got the hoovering done and hoping not to be noticed. September had settled firmly over Dorset with cool nights giving way to warm days and the leaves beginning to brittle and brown on the trees. There was a smell in the air of ripe blackberries and burning and I had an almost atavistic urge to make jam, even though I’d never made jam in my life and hadn’t even read the ingredients on the side of the jars that we always bought in Waitrose.

It was nearly seven o’clock. If I was going to meet Gabriel, then I had to get a move on. I was still wearing the clothes I’d, quite frankly, been wearing for two weeks. Washing down walls was as far as I’d got with the whole ‘redecorating’ thing, but it wasn’t an activity that lent itself to designer clothing, so it was still jeans and an oversized shirt. The rubber gloves came and went, particularly when I was cleaning floors and picking up Patrick’s poo from the orchard. The bucket had gone on timeshare.

Showering was probably optimistic. The electric shower spat alternate gobbets of hot and cold water, so the temperature was more of an average than an actual, and it had a tendency to throw the trip switch out. I settled for washing my face, combing my hair and putting on a pair of clean jeans and a T-shirt and jacket. ‘The Grapes’ could be anything from a spit and sawdust pub frequented only by locals to a gourmet bistro with a universe of Michelin stars and a clientele recruited from the TV actors that lived nearby. I reasoned that this outfit would fit in with either eventuality, and, with instructions to Poppy to finish her homework and ring me if she needed anything, I headed off.

My tiny Kia was perfect for driving the local lanes. I’d resisted Luc’s urging to buy a 4 x 4 wagon for ‘safety’, and it was just as well because the narrow road to the top of the cliff, with its overhanging bracken and hawthorn, would have challenged anything much wider. I’d not really taken much notice when I’d first visited, still too shell-shocked by Luc’s declaration that he was selling the flat, although I had taken note of the removal company’s select and ripe language when they tried to get a full-sized lorry down as far as the cottage. Once out onto the lane that ran along the cliff, things got wider and easier and I wound my window down a little way to enjoy the chilly air, which brought in the smell of the sea. Up here, away from the constricting trees, there was a feeling of openness, the fields were grassy stretches of sheep behind gates, and the sky was huge overhead. Tucked into our little hillside, we didn’t get a lot of sky, so I wound the window down further and stared up at the pinpricked blackness as it unspooled above me.

I met a crossroads and turned towards Bridport, ignoring the signs to Christmas Steepleton. I’d only been down to the little seaside village once or twice and it had been full of lorries and cars then. Presumably filming for Spindrift was under way, or at least in the heavily planning stage, and the lack of parking and actual shops that didn’t sell tourist seaside stuff had kept me from returning. About a mile along the road, which was otherwise devoid of any buildings, was a blaze of lights and a full car park. I turned in, squeezed the Kia into a tiny corner space – another good reason not to have a big 4 x 4 – and somewhat hesitantly made my way around the building to the door.

A group of people were smoking outside, all laughing and jostling over a single lighter. I had one of those moments, when you know you are a twenty-first-century woman in possession of all her rights to enter a pub, yet internally there’s still a whisper from eighteen-ninety womanhood, when going into a pub solo was the mark of a woman touting for custom. I had to seize my courage and ball it up in both hands, take a deep breath and open the door.

Nobody noticed me. I’d been a little bit worried that there might be a Slaughtered Lamb moment of quiet and everyone turning to the door, but the crowded warmth and chatter inside didn’t miss a beat. I shouldered my way in and looked around.

‘Hi there!’ Gabriel was waving to me from a corner table just inside the door. ‘Sit down. This is Tansy Merriweather, who’s been in charge of location finding until now, and Keenan, our director. They’ve got a few questions for you. What are you drinking?’

Maybe it was something about Dorset – something in the air? – that made this easy kind of familiarity breed without contempt. I found myself chatting easily away to both Tansy and Keenan, learning about Spindrift and their places in the team.

‘I’m going more over to managing the café over at Warram Bay,’ Tansy said. She was small and pretty and had the slightly scrunched-up face of someone who spends a lot of time trying to think about what they say before they say it. ‘Working too closely with Davin was making us bring too much work home. When I realised we spent a whole weekend just talking about filming, I decided it was time to get out, hence—’ She waved a hand to indicate Gabriel, who was still standing at the bar.

‘My daughter keeps mentioning Davin,’ I said. ‘You’re a couple?’

‘Yes. It’s a bit like befriending a wild animal,’ Tansy said. ‘But he’s okay really. If your daughter wants to spend some time on set…’

‘She will, if we film at the cottage.’ Keenan, who was short, plump, balding and almost the exact antithesis of what I’d previously thought TV directors would look like, said, over his gin.

‘Oh, yes, I suppose she will. But I’m handing this one over to Gabriel. I need to take more of a back seat this year, and managing the café is a bit less pressurised and has less of Davin shouting in it.’

‘Tansy’s part-owner of the café,’ Keenan mock-whispered, hooking a slice of lime over his glass rim. ‘And Gabriel is cheap and local. He’s told us a bit about your place. It sounds… well, it sounds horrible, but I expect you like it. Got any pictures?’

I pulled out my phone and showed them the estate agent’s pictures that had made me fall in love with Harvest Cottage in the first place. We discussed access and, when Gabriel finally fought his way through the crush at the bar and brought my drink over, we talked about layout and, finally, money.

Keenan named a figure that would help get us through the winter. Logs were expensive and we still needed carpet and curtains and fewer woodlice. After Christmas I would start looking for local teaching jobs again or apply to be in the bank of teachers to cover absences, but in the meantime payment for use of the cottage would get us through. It would be a squeak, but I was damned if I’d ask Luc for additional money.

We arranged a day for Keenan to come with some of the team to make sure that technicalities I didn’t really grasp would work, and then he and Tansy went off back to Steepleton, leaving me with Gabriel.

‘So, when is Patrick going?’ I felt a bit awkward. I mean, obviously this wasn’t a date, more of a business meeting, but it had been a long time since I’d been alone in a pub with a man. In fact, had I ever? I’d met Luc when I was nineteen, there had only been brief passing boyfriends before that, and Luc would have died rather than hang around in village pubs drinking cider and playing darts like this crowd.

Gabriel pushed his glasses up his nose. ‘Um. Yes. Bit of a tricky one there,’ he said, staring down into his pint glass of yellow bubbles. ‘I don’t know if Kee mentioned it…’

Actually Keenan had talked about a lot of stuff, but I’d mostly been focused on the money, so he could have mentioned anything and I might not have noticed.

‘… and it was originally a pig,’ Gabriel was continuing. ‘But I was talking about Patrick being in the orchard and he thinks a horse might work better. I mean, obviously he won’t be coming in the house, but, well. They might work Granny Mary’s van in too. So, if he could stay, just until filming finishes?’

I thought of the stomped-mud path. Of the retreating grass and the patch on the largest apple tree where Patrick rubbed his tail. Of the big face that would appear at the window and gaze balefully at me from time to time. Of the fact that Poppy kept on about riding lessons.

‘I don’t know.’ I put my glass down firmly. ‘There’s not really enough grass now. He’s going to need hay and – does your granny give him hard feed? It must take some energy to pull that van and he’s not getting that from just grass, not in winter. Does he need a rug? And a farrier will have to take his shoes off if he’s not going to be working for a while.’

Gabriel blinked at me over his drink. His glasses magnified his eyes so much that it looked like a special effect. ‘She’s not actually my granny,’ he said, and it sounded as though he’d picked on the least actionable of my statements. ‘It’s just that everyone calls her Granny Mary. She’s just been around the place ever since I was young, sort of a ubiquitous granny rather than a specific one. Sorry.’

My face had clearly fallen. I’d thought he was more intimately connected to the life of Patrick, now he was just a passer-by? ‘I see,’ I said, tightly.

‘Oh, but you’re right about him needing food, of course. I’ll… I’ll ask Granny… I mean, I’ll ask Mary about it. But, will he be all right to stay until we finish filming? It sounds as though he’s going to be an integral part of the storyline.’

Oh, bugger. I was firmly painted into a corner here. Say no to Patrick and it might risk the cottage not being used as a location, and we needed the money. Say yes, and I was stuck with a grazing machine with soup-bowl feet and a penchant for watching me boil the kettle. Plus Poppy’s growing attachment to him, which I wasn’t keen on.

Gabriel was watching me. I looked at him sideways as we sat amid the fug and chatter. There was a curious kind of stillness about him; he didn’t swivel all the time to watch the darts match or people coming and going. He just sat, hands around his pint of cider, as though life was going on around him without touching him at all. My mind briefly contrasted him with Luc, whose sociability and high-functioning boredom meant that he would have joined the darts game, bought a round for everyone in here and started at least three conversations with random strangers before we’d even sat down.

If he’d ever been so pleb as to go into a country pub, of course. Wine bars were more his thing.

I smiled. It felt stretched, as though I was forcing my face. ‘This is a nice place.’

He jerked his head in a sideways nod, but it stopped him from looking at me in that curiously concentrated way. ‘Noisy. Nearest pub to Steepleton and Landle, so it’s usually busy, but the cider is good and local.’ Then he swept a hand up and pushed his hair from his face. ‘Sorry. Am I staring?’

‘No. Well, yes, a bit.’

He gave a rueful smile and looked back down into his drink. ‘Sorry. It’s…’ He took the glasses off and laid them on the table. Without them his face looked less defensive, more classically good-looking, with the curve of cheekbones more pronounced and his eyes a more realistic size. ‘Sight’s degenerating. Even with these it’s not great, and I can’t wear them any thicker or I’ll topple over.’

I didn’t know what to say, so I just sipped my orange juice.

‘The location job is a pity posting, y’see.’ He picked up his glasses and turned them over between his fingers. ‘I’m going to be functionally blind in a few years.’ The words were matter-of-fact, but there was emotion quivering behind them. ‘So I’ve got to earn while I can.’

I had no idea what to say to that. Part of me wanted to do what I would have done with Poppy, thrown out ideas, things to be looked into and researched. But the rest of me knew that wasn’t what he wanted or needed. This wasn’t a problem to be solved, it was a life-altering reality.

‘It must be hard.’ I hoped I’d injected enough sympathy into my voice.

‘Pretty shit, yes,’ and the half-laugh in his tone told me I’d done the right thing. ‘And I’m telling you just so you know that I’m not being a total bastard about Patrick and the van. I’d help you out with him only, well, I don’t know much about horses and I can’t see well enough to pick it up on the fly.’

‘He needs some hay and a hay net, at the least. Otherwise he’s going to start losing condition, and it will be hard to tell under that winter coat he’s growing.’ I sipped down the last of the orange juice.

‘Were you one of those pony-mad children?’ He’d left his glasses off, and it was interesting watching eyes that weren’t intently fixed on something. He was looking at me directly, yet from what he’d said he couldn’t really see my face that well.

‘Something like that.’ I put my glass down firmly. ‘Well, I ought to get back. Poppy is fine left alone for a while, but she’s still a bit nervous of the quiet.’

‘Poppy’s your daughter?’

‘Yep. Fourteen and city born and bred. Although I don’t much think it matters where they are from, fourteen-year-olds have “attitude” fitted as standard.’

Gabriel smiled. It was a nice smile; it crinkled up those impeccable cheekbones and made him look more approachable. ‘There’s going to be a fair bit of noise and disruption when we film at your place. How will she cope with that?’

‘She will be in her element. Noise and disruption are what she’s all about. On her own terms, naturally.’

‘Naturally. We were all fourteen once, weren’t we?’ He put his glass on the table next to mine. ‘I’m sorry? Did I say something?’

‘No, no…’ But the cold finger of memory had stroked its way down my spine like a ghost in this warm, companionable room. ‘No, I was just… anyway, I’d better go.’

‘I’ll walk you to your car.’

He stood up too, tall enough to cause the darts players to shout, ‘Oy, shift over, lanky!’ when his height intruded on their game.

Although the shout was good-natured, Gabriel did a sort of half-hunch, where most men would probably have raised two fingers and shouted back. He scuttled alongside me out of the pub, where the night air met us clear and chilly. ‘Sorry about that.’

‘They were just being idiots.’ I unlocked my car and we stood beside it for a moment. He looked as though he was weighing up the best way to take his leave. ‘Do you need a lift anywhere?’

‘A lift?’ he asked, as though this was the most bizarre suggestion anyone had ever made.

‘Yes, you know, you sit next to me and I drive my car where you need to go. Lift. It’s not an abstract concept.’ I hoped he’d accept, because I wasn’t sure whether I was going to go for the handshake businesslike farewell, or whether a cheek kiss might be more appropriate. Long exposure to Luc and his family, combined with much living in France, had made the cheek-to-cheek double kiss almost automatic, but I had to remind myself that in rural Dorset it probably meant you had to get engaged or something.

He shook his head. The slight, but nippy, breeze was tossing his hair about and he pushed it back with a hand. ‘Yes, sorry, I know what you mean, it’s just that I’m only a couple of miles from home, and the idea of driving that short a distance is odd.’

‘I thought you lived in Bridport?’ I remembered him saying something about it not being easy to find Patrick accommodation because of where he lived.

‘Well, I do, but I’m staying in Christmas Steepleton while I’m doing this location work. With my sister, Thea – she’s got a little flat over her shop. It’s easier than coming in every day on the bus.’

‘Oh.’

‘So, goodbye, then. I’ll come over in a couple of days and bring you the contract, show Keenan the place, that sort of thing.’

I sort of held out a hand and went for a cheek kiss simultaneously. He saw me lean in at the same time as his hand went out, and we ended up punching each other in the ribcage whilst banging our heads together as we tried to pull out of the ‘kiss’ situation without making contact. ‘Ow,’ I said, although it hadn’t been hard enough to hurt.

‘Sorry.’ Gabriel rubbed his chest. ‘That was…’

‘Awkward, yes. My fault, too much French kissing. Oh, no, I don’t mean that, I mean I’ve spent a lot of time in France. I teach French. And my husband was French. Is French,’ I gabbled, trying to cover up the fact that my face was so hot that it was probably summoning help from nearby villages, like a beacon on the cliffs. ‘So, yes. Goodbye.’

I got into the car and drove out of the car park with my window wound down to try to cool my cheeks.