Читать книгу Stories From Under The Carpet - Jane Turton - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

William Aedy, 1888

ОглавлениеWilliam Aedy was the adventurous type, and perhaps he liked to push the boundaries.

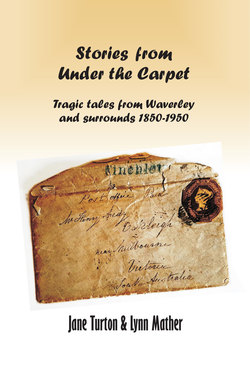

He was the fifth of six children born in Finchley, North London, in 1831 to Edmond Aedy and Nancy Pope.⁵⁸ At the age of 20, William left England aboard the ship Success, arriving in Geelong in 1852.⁵⁹ Because of the gold rush that had begun in Victoria the year before, more ships brought passengers to Melbourne than to anywhere else in the world.⁶⁰ William possibly tried to find his fortune on the goldfields. Two years later his older brother Henry sailed to Melbourne aboard the ship Daylesford⁶¹ and the two went to stay with an aunt in Oakleigh in the Parish of Mulgrave, east of Melbourne. Aunt Louisa and her husband Emmett Charles William (William) Wentworth had arrived in the colony in 1849 aboard the Mary Shepherd.⁶² Perhaps William Wentworth had written home to William Aedy encouraging him to come and work the land in Victoria. William and Henry’s mother Nancy never gave up hope that her boys would return to England and help on the family farm. She sent them letters asking them to come home until her death in 1873. But sadly, neither son had the chance. Amazingly, Nancy’s letters still reached her sons in Oakleigh, despite her convoluted postal instructions, shown below.

Letter to William and Henry from their mother. Source⁶³

By 1856, William and Henry had become landowners – together paying £60⁶⁴ for sections 19 and 21 of Crown Portion 45 in the Parish of Mulgrave, buying the land from their uncle, William. William Wentworth had purchased the same property two years earlier for £136⁶⁵ – more than twice the sum. Was Uncle William giving his nephews a helping hand by selling his estate at a significantly reduced amount?

The following year another block in the same Crown Portion was sold to John Francis Moore. John and his wife, Faithful had arrived in Victoria in 1853 aboard the Arabian.⁶⁶ They had a large family, although William only had eyes for their eldest daughter, Rebecca Jane. By 1863 Rebecca was only 18 when she and 32-year-old William married and settled on sections 19 and 21.⁶⁷

Disaster struck the brothers when Henry died suddenly of liver failure in 1865.⁶⁸ He was 36 and is buried in the Oakleigh Cemetery.⁶⁹ He had never married.

Map of area courtesy of Clive Haddock

A year before William and Henry had bought their land, Richard Gardner Cooke sold sections 23, 25, 27 and 29 in the same Crown Portion of land to Mark Frederick Ogle, a pharmacist living in Maryborough more than 185 kilometres west of Melbourne.⁷⁰ Ogle had once lived on the land but had not done so for many years.

William and Rebecca like many couples of the time had 11 children – three boys and eight girls. Two of the boys did not survive past infancy.⁷¹ The other children grew up on the family land in Boroondara Road, Oakleigh, or what was later known as Collins Street in Chadstone.

For reasons unknown, on May 26, 1881, William Aedy signed a statutory declaration that he had had uninterrupted possession of Mark Ogle’s ten acres of land⁷² in sections 23, 25, 27 and 29 on Crown Portion 45. Aedy declared that since no one had tended the land or lived on the property for many years, he had fenced in the area and paid rates for 16 years. He stated that he was unaware of anyone else who claimed to own the property. So, Aedy claimed the land as his own under laws of ‘adverse possession’ and had the land brought into his name under the Transfer of Land Statute.⁷³ The land transfer occurred on March 15, 1882.⁷⁴ Why did Aedy commit this illegal act that was to have such a devastating impact on him and his family?

Unfortunately for Aedy, his statutory declarations to Thomas Irwin JP and therefore his application to the Land Titles Office were subsequently proven to be false. James John Smith, a local farmer, had for some time been the tenant on the land in question. In 1857, Smith had taken out a five-year lease, using the land to cut wood and grow some crops. When his lease was up, Edward Stocks, another local market gardener, with the permission of Ogle, then used the land to graze his cows. Ogle claimed his brother-in-law would collect the rent, but after Smith had ended his lease on the same land, and Ogle’s brother-in-law had died, Ogle hadn’t followed up with further tenants and had left the land vacant. When Smith became aware that Aedy had ‘jumped the land’ he wrote to Ogle to let him know.⁷⁶

Fraudulently obtained Land Title. Source⁷⁵

Ogle enlisted the services of solicitor, Lewis Horwitz, to settle the situation. In March 1884 Horwitz confronted Aedy and accused him of stealing his land. Horwitz showed Aedy the letter Aedy had written to Ogle in 1875 in which he asked to rent or purchase the land, which ultimately proved that Aedy had known that Aedy owned the land in the years he claimed it was vacant. After Horwitz’s visit, Aedy agreed to go to the solicitor’s agent in the coming days and apply to have the property transferred back to Ogle and cover any costs he had incurred.⁷⁷

But William Aedy never went to the agent’s office to change the land title, nor did he pay a penny towards Ogle’s costs. After years of trying to restore title of the land to Ogle, Ogle issued a writ against Aedy in January 1887, and on August 4, 1887, Aedy stood trial in the Supreme Court, Melbourne. He was ordered to make arrangements for the transfer of the land into Ogle’s name and to pay costs of £50. Mark Ogle had initially asked for £1000 damages, compensation for him being deprived of the use of his land, although the court did not believe he had tried to access the property for many years.⁷⁸

The Argus newspaper printed a comprehensive description of the case on page nine of the paper on Friday, August 12, 1887,⁷⁹ highlighting the inconsistencies in Aedy’s story. He had lied about his knowledge of the land’s true owner, and the date on which he claimed to have occupied it. In fact, the Mulgrave Shire rate books do not show any evidence that Aedy had paid the rates as he claimed to have done.⁸⁰

Eight days after the court ruling, when Aedy had still not paid the money, a new writ was served on him via his lawyers.⁸¹ William had no way to pay his debts, and his mental health was unravelling. On August 30, 1887, William Aedy entered into an arrangement with a local landowner and farmer, Thomas Tuhan to buy William’s land and all his belongings for £700 Sterling. Aedy instructed his solicitors to use the money to pay out his mortgage and all his debts and legal fees, including that owed to Mark Ogle and Crisp and Co., solicitors.⁸² ⁸³ But it appears that William Aedy neglected to tell his wife Rebecca that he was selling everything, only that he was taking a loan to re-mortgage the property.⁸⁴ He explained away a large amount of money he suddenly had as gifts from supportive neighbours helping the family out of debt.⁸⁵

Meanwhile, Aedy’s case had come to the attention of the Commissioner of Titles, Edward Theophilus de Verdon who had read in the Argus the outcome of the case⁸⁶ and being relatively new in his role was keen for a clear message to be sent to those who had been ‘jumping land.’ He wrote to the Attorney General. In his letter, Mr de Verdon said he had read the transcripts of the case and passionately encouraged the Attorney General to consider laying criminal charges of fraud against William Aedy.⁸⁷ The Attorney General agreed, and on September 5, 1887, William Aedy was arrested in Oakleigh.⁸⁸ Two days later he was granted bail on a surety of £200, paid by his brother in law Felix William Rolland and a local farmer, Michael Hoban, who had once run the Waverley Arms Hotel in Waverley Road.⁸⁹

On November 8, 1887, the sale of William’s land and personal property was finalised,⁹⁰ and two weeks later Aedy stood trial in the Melbourne Supreme Court. He was convicted of perjury for making specific false declarations. Justice Thomas A’Beckett, who in 1909 became Sir Thomas A’Beckett,⁹¹ also found him guilty of fraudulently procuring a Certificate of Title. It had become apparent during the trial that William, although deserving of a gaol sentence, was deemed mentally unstable by virtue of his despondent manner concerning the authorities. Justice A’Beckett acknowledged the impact that the trial had had on him and discharged Aedy after fining him £50.⁹²

Mr Justice Thomas A’Beckett. Source; State Library Victoria⁹³

After the trial, Rebecca Aedy described her husband as despondent and occasionally deranged. She was concerned about his mental wellbeing and called a doctor. Rebecca had not considered that William would hurt himself, but she kept a close watch on him, fearful that he would wander off and not find his way home.⁹⁴ Sure enough, at 3 am on January 5, 1888, Rebecca woke to find William awake and agitated. An hour later she woke again to find him gone.⁹⁵ With her 19-year-old son Edmond, she began a search of the buildings on the property. They found William in the larger shed, hanging by the neck from a rope tied to the beams in the roof.⁹⁶

William was buried in the Oakleigh Cemetery. A memorial brick there records his name, but with the wrong date of burial.

William Aedy, memorial brick in Oakleigh Cemetery. Photo; J Turton, 2018

It might be easy to assume the Aedy’s tragedy ended with William’s untimely death. But this was not the case. A year after his death Rebecca sought to finalise his estate and applied for letters of administration, itemising all land and personal property she and William had owned. She acknowledged the £800 loan plus interest she believed she owed Thomas Tuhan. After notice was made in the Argus of the intention to apply for probate, Thomas Tuhan came forward to claim that William had sold the land and all property to him.⁹⁷

In March 1889, Rebecca was in court again defending herself against Thomas Tuhan who now declared the Aedy land was his. Without access to court transcripts, it is impossible to know what lawyers for each side argued in court. Perhaps the court found Thomas had taken advantage of a mentally unstable man. Or the judge sought to protect an innocent widow. Either way, the case was thrown out, and Rebecca retained the land in her name.⁹⁸

It was not the end of Rebecca’s woes. In March 1898, her youngest child Margaret died of tuberculosis. She was just fifteen. Five weeks later, Rebecca too died of the same disease. She was 53. Mother and daughter are buried together in the Oakleigh Cemetery.⁹⁹ ¹⁰⁰