Читать книгу Physics of Sunset - Jane Vandenburgh - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Outdoor Survival Skills

VERONIQUE CHAKRAVARTY GREW up in a little town in the south of France—she called it my veellawwge. The sun rose there over golden hills to shine on a river crossed by a Roman bridge. The scape of land eees similar to theees one, Veronique said. She pressed her lips together, looked out from her hill above the water of San Francisco Bay, then gestured in the dismissive way that showed she, being French, was superior to either of the two perfections.

The light, she asked. And this air? Veronique smiled at Anna, who examined the atmosphere as if it were gauze between her fingertips. The light was clean and white, the air soft to the point of feeling powdery, as if it contained particles that multiplied light’s brilliance. California was dry, Mediterranean, and shadows did fall in that sharp-edged, bluish way, but it was the molecular density of Veronique’s soul that had allowed her to be transported intact to her new land from that more ancient one, Anna knew, and allowed her to feel at home.

Springtime, a bright morning, the air cool on Anna’s naked arms. The past winter had been rainy so the hills were lushly green. A soft breeze moved up the Chakravartys’ canyon.

Veronique had attacked the landscape like one of her Roman ancestors scooping out irrigation ditches, adding sand to the clay soil of the deep beds she’d dug into the terraced hillside. Her kitchen garden contained the same herbs and vegetables her mother grew: tomates, aubergines, persil, asperges. Veronique came, behaved as a conqueror, the earth responded, was changed by her.

And the local idiom was being altered by the force of Veronique’s will. Anna Bell-Shay was a poet and had a hesitation in her own speech that encouraged her habit of listening carefully. Head down over the basting of a satin blanket binding or in the active grief that had yawned open for no good reason in the middle of her life, Anna attended her friend’s various beats and breaths and emphases, unreasonably imagining Veronique Chakravarty was somehow teaching her fluency.

English was becoming ever more complex to Anna as she grew older. In the matter of a dash, for instance: how much pause might a dash be asked to carry? The dash was modern, also seemed to contain all of history. All her favorite writers seemed to balance there and so exist in the tentative.

Veronique didn’t worry about this kind of thing. She went crashing off through the underbrush of everyday speech, imagining, for instance, that people rushing to their therapists were going to see their shrimps. This was Berkeley in the 1990s, where everyone was, or had been, or soon would be in some variety of therapy, the latest being traveling to the far-off reaches of the world to walk the most famous labyrinths. Veronique’s husband, who was from Delhi, had an almost better than perfect English. It was elegant, carefully nuanced, slightly archaic. Because of Ravi, Veronique said cawn’t and shawn’t, she rode a lift, lifted the bonnet of the caw she’d hired.

Ravi’s was a high old culture, his wife’s more new and raw. His eyes gleamed, were deep-set, thickly lashed, so brown his dark glance might catch, take hold. His gaze possessed a person—Anna felt it grab the muscles of her lower belly in a cramp that was frankly sexual. Ravi and Anna sometimes locked eyes at dinner as Veronique plunged on and on—he might lift a brow or move his full lips slightly at something his wife just said. Ravi very pointedly did not correct her, seemed also arrogantly to defy anyone else to do so. Anna understood this. She suffered the same attraction. Veronique’s being so noisily alive being why each was drawn to her.

The Chakravartys lived up the hill from Anna and Charlie, whose older house lay in the flats of Berkeley in the section of Northside called the Gourmet Ghetto in the real estate ads. Anna and Veronique had had babies within weeks of one another, their friendship—Veronique called it free-end-ship—had deepened over upchuck and earaches.

Nearly all aspects of early motherhood were without intellectual challenge, they soon discovered—even talking about children was often boring in the particularly overeducated way of the developmental psychologist, whose clinical language made Anna feel she might need to shoot someone. She might feel better, she often thought, if she killed something. She would probably need to commit one small crime some day soon. She needed to turn criminal or she needed to go book an hour in a Tokyo sleeper. These were the modular sleeping capsules she’d just read about. Japanese salarymen rented them so they could power-nap on their lunch hour in order to be rested enough to go out drinking with their bosses again.

Anna’s own mother confirmed it: infants are no more wonderful than any other subset of humanity. God does, however, make all small mammals look cute and smell good so you’ll want to nurse them, Margaret Bell said when she telephoned. Also make you less likely to toss them out a window.

Anna and Veronique sat together on the Chakravartys’ wide deck, their children playing nearby. The light shone on water radiant as aluminum—they seemed to sit in a bowl of noon. With pregnancy Anna, who was blond and fair, developed new sensitivities; she now had a form of sun allergy. She wore big loose dresses and a wide hat and huge, very dark dark glasses to protect her pale eyes. Charlie called this Anna’s Edith Phase—Edith was Anna’s own unlovely middle name. He sometimes said to people that if life was a costume party, his gal Edith was going to come dressed as the echt artist/mental patient. She’d arrive with her head swathed in bandages, ear gone, her face all smeared with white stuff, dressed as Mrs. Vincent van Gogh.

It was the chemistry of pregnancy that changed her, Anna thought. Her mind turned dull as her skin became more sensitive. She was a prism now through which light fell and broke apart. If what Anna was experiencing was a natural splintering of focus, as her mother suggested, when was it that she might begin to pull herself back together? Anna had once been smarter—of this she was nearly certain. She recently called her mother to ask if this wasn’t so. Margaret Bell now lived year-round in upstate New York in what had been their summer house.

It was natural, her mother said, that the soul of a female person should be riddled by empathy. This was a natural adaption. That mothers were porous to the wishes of those around them was what had kept humanity lurching from meal to meal all down through recorded history. She was herself now finished with that portion of her life, Margaret said, having relinquished responsibility for the heavy organs of appetite to the new generation. This new lightness was one of the surprising and very wonderful things about being a grandmother.

Days ticked by. Anna’s daughter was one year old, now turning two. The photosensitivity began to ease. Anna often wanted nothing more than to go alone into an art museum, to stand in front of a great painting and be sliced apart by all the levels and degrees of silences. A great painting made its own quiet room. What she disliked most about poetry, she’d discovered, was that it seemed to so depend upon the noisy apparatus of language.

Until Anna witnessed it from within—experienced in her body the nubs of what might have once been deemed a personality being so rubbed down and burnished—she’d never been so attracted to people as ardently selfish as Veronique sometimes seemed.

Anna became so diffuse at times that she felt intoxicated by the mere presence of any other stronger individual. She experienced this as a profound psychological calamity, a loss of self. The experience felt tidal, she became rapt, went out, it might take days or even weeks for her to come back in again. This happened both with women and with men. Writers, in particular other poets, in particular other women poets of about her age, were most necessary to avoid, particularly those who were beautiful or might turn out to be honestly talented or to exhibit some originality. It wasn’t the threat of her own plagiarism, so much as Anna’s worry that she might be swept so easily into their sea, actually begin to be subsumed by them.

Anna loved Veronique because she was French and the French are a stubborn race that refused to be eradicated. Veronique also refused to kneel and worship at the altar of maternity. She said the things that Anna needed to hear in order to keep her sanity: that playing Legos isn’t fun, that almost all children’s literature is intrinsically inane.

The Chakravartys’ house overlooked that of Alec and Gina Baxter. Alec was an architect and theirs was a famous house in Berkeley, poised on the opposite side of Ravi and Veronique’s canyon. Very chic, Veronique said sometimes, looking down her French nose at it. Very BCBG, I suppose, but do you actually like eeet?

Anna was too porous to decide. The house was clean and modern. In a certain kind of light at various times of day, its surfaces became invisible, the glass side going sun-gone, the tint of the walls inside matching that of a whitish sky. The house shifted, changed size and shape, was sometimes nothing more than the reflected patches of scrub oak and evergreen standing against a brushy hillside.

The house was large enough to have been imposing except for its tendency toward atomic dissolution. It was also somehow a little out of place in Berkeley, Anna thought, as if it landed there not from the future but from another parallel reality, the lost world that would have taken the place of this one had things gone slightly differently. It was there, in the world beside the world, that Anna felt she actually resided rather than in the real town of Berkeley, California.

And while this town, with the university at its heart, harbored more Nobel laureates than any other and there were other major and minor geniuses of every kind all up and down its social ladder, Berkeley had the pretense of hating pretense. It preferred its geniuses dead, its great houses to be wooden and old, foursquare and democratic, like those designed by Bernard Maybeck.

I ated that ouse, Veronique said to Anna one day, ated them for making it. Then when the lorry comes and I see they ave that what eees theeeese thing? theeeese baby swing? and my hurt breaks for them and my ope flies up again.

So it always honestly did come to the same sad questions, Anna realized, the ones all the interesting women they knew struggled with: How to negotiate the inward and outward currents, when the job of making a household ran against the pull of a worldly ambition ? How was anyone to accomplish this once mute and simple act, that of raising children? And how, in the face of the awesome privilege she and her friends enjoyed, to justify these twin burdens of despair and jealousy?

The disappearance of the mass of the Baxters’ house seemed to be a poetic technique Anna might study and employ if she ever wrote again. She envied the painters, like Gina Baxter, or the architects, like Alec Baxter, those who made wordless physical objects, who put walls up, hung paintings there, things thick with dimension, dense objects that didn’t depend upon the little markings that made letters that stood for sounds upon a page.

She and Veronique drank wine as the sun went down, Anna watching the Baxters’ house as its essence changed. How to be completely and truly present on the other side of the work, she wondered. How to give away nothing yet still speak with intimacy? How to become spare and empty without indulging her own strong impulse toward self-annihilation?

Anna had done her graduate work in Emily Dickinson—she hadn’t finished her dissertation. Not finishing her Ph.D. now seemed emblematic of everything that was turning out to be wrong with her, motherhood being corollary to that earlier vanishment. When she was in graduate school, she’d once attended the reading of a paper called “On the Anonymity of Mothers,” concerning the mothers of various early presidents of the United States about whom almost nothing is historically known, often not even the dates and places of their birth.

Anna, who was tall, had been taught by her mother to stand up very straight. Forgetting herself as completely as she did, she remembered the length of her body sometimes only when she abruptly stood and was made dizzy by the altitude. As she stood to ask a question at the end of the paper’s presentation, and an old embarrassment swept through her, that of the big, shy, sweating girl, the awkward adolescent with enormous feet who’d always tried so hard to stay anonymous. She began to blush, to stammer, spoke softly, haltingly, then sat down, having become too nervous to even listen to the answer. And so it was, she saw, that self-consciousness might prove terminal, the inescapable gravity of constant self-reference. She was flame-faced as she left the hall, ashamed, ashamed too of being ashamed. Her hot face pulsed with every heartbeat going me, me, me.

Ravi traveled; Veronique was stuck up the hill at home with theee keeed. She now had two babies, but Veronique didn’t bother with an s to form the plural. Veronique, who was bored, sometimes watched her neighbors with binoculars. The Baxters had uncurtained windows. They were an attractive couple, one so big he was almost lumbering, the other diminutive, each dark-haired but with mysteriously fair-haired children, all moving through the spacious wood-planked rooms as if on their way somewhere. Alec was well over six feet, so tall he needed to bend over with his face gone grave and solemn to listen as his wife spoke. Gina was stylish, antic. She talked and talked, Alec listened. Gina had stopped growing quite early in adolescence, Veronique said. It was all her various tragedies, she added, somewhat callously.

Gina Baxter was now very busily accruing some notoriety, having recently gone beyond painting to work both behind and in front of the picture plane. This was her return to realism. Gina did seem poised on the brink of something—her friends had begun to eye her cautiously. The odds against her turning out to be any good at all were, of course, absolutely astronomical, Anna knew, the Bay Area being something of a backwater in the plastic arts. The lucky people, Anna thought, were people like Veronique who never noticed the difference between what was good enough and something that might actually matter. That was art’s secret trick, Anna thought, that so few did it well, that no one knew exactly why.

Ravi, in electronics, was getting quietly rich. Veronique had never been more miserable. Come up ere, Veronique demanded. Bring that one up ere to play with theeees one. Stop and buy me a pack of cigarette. Do this, Awe-naw, or I will keeeel myself.

Veronique, who’d quit, was now back smoking Marlboros—she called them theee Red Death. She smoked as she painted cowboys and Indians in oils on the walls of one bathroom. She painted faux naïf tepees and saguaro cactuses, all of this awkward, childlike. She used unmixed colors straight from the tube—raw umber, burnt sienna, cadmium red—and as she painted er ope rose up again.

It was art that did it, Anna knew, the act of being within the moment of creation, that lit the dim places in the brain with the thought of the other, better, more fully imagined West, the place the real desert sun still rose and set. It was there, in art, that the neurons gained the power to come alive and fire across the great bow of eternal darkness.

Despite herself, Anna found her own hope rising too. She had Maggie, the little girl born as a kind of miracle so late in her marriage she had already lost all hope. Her book of poems would be published by a respectable press in a year or two. She had a marriage that was probably as good as most, at least as good as the one her parents had—she thought of her own marriage not as a deepening spiritual bond, rather as a kind of equity of all the many years she and Charlie had each put in.

Anna believed in making poems as anyone might hold to any religious faith, that a hurt and broken world was made more whole by these irrational acts of faith. God existed, if He existed, in all enactments of love and grace, in every gesture made toward creation. Anna believed this. She also believed writing a book of poems was almost exactly like lighting a box of kitchen matches, one by one, and pitching them down a well.

They sat out on the Chakravartys’ deck in good weather while Veronique, who had never heard of sunscreen, became tan, and their children grew and Anna basted satin binding onto the quilted baby blankets she made for charity. Maggie was getting bigger. A poem, or some lines in one, sometimes broke free, ran wildly, then came back to her in snatches, like the lyric of a song she was only now remembering.

Anna slept with a handsome man who, while mocking, was nice enough. He was reputed to be her husband. Charlie Shay was an experimental musician who taught at a women’s college in East Oakland. He was startlingly good-looking—she’d recently begun again to notice. He was even better-looking than he ever used to be. This was not a man who was going to lose his hair or thicken around the middle. Charlie got on his mountain bike nearly every morning and rode it straight uphill to Grizzly Peak, his bright cheeks there cooled by the dazzling fog.

Anna’s mother called to ask what fruits and vegetables were arriving in the market, to hear what Maggie was now up to. Margaret Bell fretted over her daughter’s lack of happiness, more noticeable since Maggie had been born. It was a nullity that came and now resided. It manifested physically, an emptiness framed by the muscles of Anna’s lower abdomen. She could never tell her mother this. She often felt a little sick, also ashamed of feeling sick. Her mother was Yankee, tough-minded, stoic. Anna had nothing real to complain about.

The Cold War had ended, the wall in Berlin came down, but Anna was still at times so panicked her hands shook, terrified she couldn’t save her daughter from an ecologically imperiled world. She awoke in the middle of the night to the indelible vision of a black sun rising over a nuclear desert, the sky a cold and quiet blue. This was the color Georgia O’Keefe discovered by looking through the white eyehole of a sun-bleached cow’s skull.

Anna still referred to her own husband by both his names, Margaret mentioned. Was it that Charlie’s first and last names were like his longitude and latitude? she asked. Was Anna, after all these years, still trying to get a fix on him?

Anna was startled by her mother’s comment. If she complained, she didn’t mean to, as complaint made her feel petty and disloyal. She did lately worry that the man she thought of as “Charlie Shay”—this went back to their days at Stanford when there were several Charlies in their circle—might lack something that seemed increasingly essential, the vacuoles of irony that bubbled up in a personality at the level of the cell.

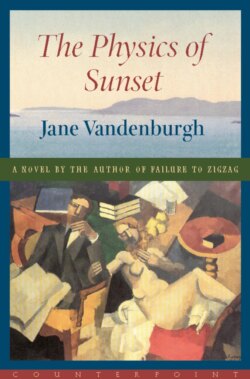

When, for instance, Anna told him she intended to call her book of poems Outdoor Survival Skills, Charlie lifted his clean, strongly muscled face and gazed off so intently that a hot saltiness rushed to fill the back of her mouth. She looked down at the uselessness of her upturned hands, long fingers that lost feeling in the cold or rain. The two were out to dinner, were having lobster and champagne. She swallowed hard against the same ache that rose from her belly and now settled in behind the muscles of her jaw. Her throat closed, she’d never known such emptiness. Would she ever meet a man for whom she didn’t need to explicate?

Anna’s throat ached, her heart ached. She was thirty-eight years old. She’d been married for more than fourteen years, and still hadn’t found the road, she recognized, the one that would lead her home.