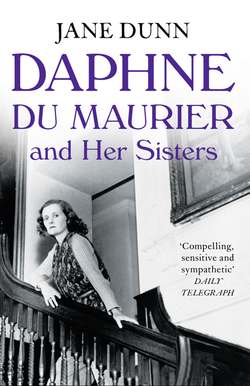

Читать книгу Daphne du Maurier and her Sisters - Jane Dunn - Страница 10

Lessons in Disguise

ОглавлениеSisters? They should have been brothers. They would have made splendid boys.

NOËL WELCH, The Cornish Review

CANNON HALL WAS the du Mauriers’ last London home. The family moved there in 1917 in the darkest days of the war, and life for the girls aged thirteen, ten and six changed for ever. The house was much larger than their town house at Cumberland Terrace, and Hampstead Heath was a vast wild territory on the borders of urban civilisation, so much more alive with possibility than genteel Regent’s Park. The Hall’s gardens were enormous and beckoned the sisters into a private world of make-believe and adventure, a place where they did not have to wear coats and hats when they went out, while the wider horizons of the heath were just a hop and a skip away. Gerald was earning a great deal of money from his continued successes at Wyndham’s and, proud of his elegant new house, he imported furniture and objets d’art to match its early-Georgian splendour. The historical paintings he bought to grace the theatrical staircase impressed Daphne most: a mournful portrait of Charles II, a vast battle scene, food for many re-enactments, and a portrait of Elizabeth I, majestic on the stairs, made every trip to bed full of fascination and not a little menace.

The most dramatic change for the du Maurier sisters was school. For the first time in their lives, Angela and Daphne were to mix with a group of children and adults who did not belong to the glamorous circle of their parents’ acquaintances. It was an alien experience that ten-year-old Daphne, self-sufficient and already armoured against the world, thoroughly enjoyed and Angela, three years older, nervous, conscientious and over-emotional, loathed. The school was a small private establishment in a large house in Oak Hill Park, a road in the leafy suburbs of Hampstead. It was owned and run by an elderly, strict Scot called Miss Tulloch. Elizabeth Tulloch, like many schoolmistresses at the time, was an unmarried woman whose energies and talents had few outlets apart from teaching. She had established her school in 1884 and at sixty-seven was at the end of her career when the two, largely unschooled, du Maurier girls turned up on her doorstep.

Angela and Daphne walked to school every day with satchels on their backs to enter very different worlds. Daphne had a sympathetic teacher who thought her stories were the best in the class, but her spelling and handwriting were atrocious. Daphne was not particularly troubled by this criticism, although she was miffed that another girl won the short story competition with an inferior tale but better presentation. She quickly became leader of a gang of girls who intimidated any classmate who displeased them by threatening to burn her at the stake. The punishment was straight out of Daphne’s historical re-enactments. She enjoyed being able to exercise her imagination and power on a bigger stage, and with a larger cast than just two sisters.

Angela admitted that she was terrified of the teachers from the start and was unprepared for the classwork, particularly arithmetic – an arcane mystery she would never fathom. Unfortunately her teacher was a fearsome Miss Webb who attacked her fumbled sums with a forbidding blue pencil and little sympathy. Maths homework was a torture and so many tears were shed that Gerald, unable to make sense of any of it himself, would ring up his business partner for help. What appeared to upset Angela as much was the chaos and noise of nearly two hundred girls going about their school day, banging desks, their feet thumping carelessly on wooden boards, their voices raised; she had been brought up to creep noiselessly from room to room while parents slept, not to chatter and laugh in corridors and stairwells. Her only companions previously had been her well-behaved younger sisters and polite adults. The cacophony of girls en masse alarmed her, until she discovered a few nice quiet girls like herself. But it was these quiet girls who revealed the real truth of how babies are made and thereby destroyed, by Angela’s own admission, her trust in her parents and stunted her social development in adolescence and young womanhood.

The school got to know of these clandestine conversations and Muriel was summoned. The shame of her mother’s wrath and her own horror at the grotesqueness of sexual intercourse meant Angela’s reaction to the next incursion of her safe world was even more extreme. Every day on their way to and from school, the sisters would walk along a lane so secluded it seemed almost to be deep country. Just another morning turned into a day that Angela would not be able to recall without shuddering. She noticed a wounded soldier in the lane. The sisters had been taught to think of all soldiers as heroes. Their soldier-uncle Guy had died defending his country, and their young cousins were still fighting the Germans, one already killed before he had grown to be a man. This young soldier before her was not only wounded, and therefore even more heroic in Angela’s naïve imagination, but was wearing a uniform of the most beautiful celestial blue. The colour so attracted her that she gazed at the man full of sympathetic feeling.

Then, this embodiment of courage and virtue, exposed himself to the schoolgirls. Angela was shocked and bewildered at the betrayal of his noble appearance and the sight of this terrible dark hidden thing. She was naturally highly strung and quite ignorant of the naked male body and had certainly never seen a man’s genitals before. The shock was compounded many times by the fact she had already been sworn to silence over the previous schoolgirl debacle. She had been forbidden by her mother to mention anything about sex to Daphne, who was walking beside her and, lost in her own thoughts, completely oblivious to the situation. Angela could not turn to her, in fact felt a sense of responsibility for her – slightly misplaced in this case as Daphne, more intellectually curious and emotionally detached, would not have been so disturbed by the situation. In fact, Daphne was to be shielded from the facts of life until she was eighteen when, enlightened by a school friend, was astounded: ‘What an extraordinary thing for people to want to do!’1 But twelve-year-old Angela, more confused and distressed, could not even confide in the girls at school as, after the earlier showdown with her mother and Miss Tulloch, the small group of sexual know-alls there had been dispersed and warned not to talk of such things again.

So Angela’s shock of discovery combined with disgust and fear was internalised. Years later she insisted there was no exaggeration in her description of the devastating effect these two incidents of sexual revelation and the accompanying secrecy, silence and shame had on her development. She became self-conscious, she said, felt an uneasy burden of taint and alienation, her mind straying to ghastly imaginings when confronted by any recently married woman. Hers was an elephant’s memory, she declared, and her scared younger self lived on within her well into adulthood. ‘Not for many years did I tell anyone, and for what it’s worth not for more years than anyone would believe possible could I bear to think about a man, much less look at one.’2 Instead, she retreated to the safer alternative of idolising her male cousin Gerald Millar, nine years her senior and already fighting in the Great War (in which he would be awarded the Military Cross). A girl given to serial crushes and longing for affection, Angela inevitably fell in love with the head girl at school but gained emotional satisfaction by imagining marrying her off to Gerald, with nothing more than a chaste kiss between them: ‘Love to me meant romantic young soldiers in khaki, Keeping the Home Fires Burning, the Prince of Wales, Handsome Actors, Beautiful Actresses, and falling in love, and no sex in any of it.’3

Not surprisingly perhaps, Angela and Daphne’s schooling at Miss Tulloch’s was soon over. They attended for four terms, punctuated by most of the childhood diseases they had so far evaded. Angela thought they were withdrawn from school once a uniform of neat blue gym tunics was mooted; their parents would rather their girls gave up their education than their pretty print dresses. But a more serious reason occurred to Angela in middle age: their parents, particularly Gerald, were militant about maintaining their daughters’ innocence when it came to sex and they feared what the girls might learn ‘in giggled whispers from our contemporaries’ about ‘the wicked World’.4

Silence and ignorance were not bliss, as Angela painfully discovered when she and Daphne returned to the routines of nursery life to continue to learn what they could with a nursery maid as teacher. The du Maurier parents did not value academic education for their girls. The maid was already engaged in trying to teach six-year-old Jeanne to read, but luckily both older girls were already keen readers and they absorbed much about history, writing style and romance from the adventures of Alexandre Dumas and Harrison Ainsworth. Angela and Daphne became well informed on the most arcane and melodramatic elements of Louis XIII’s France, Guy Fawkes, witches, London’s Great Fire and Great Plague, and executions through the ages, but they were not learning much about life in their own rapidly changing century. German Zeppelins overhead occasionally broke the Hampstead calm, sending the family and their servants running for the cellar, shattering Angela’s already over-sensitive nerves, but no one really discussed the drama that engulfed them all.

Beyond the graceful façade of Cannon Hall, beyond the garden parties and glittering first nights at Wyndham’s with Daddy and Mummy, their supporters and friends, the world of 1917 was convulsed by total war. In England, the movement for female equality and emancipation was gaining support, with women from all walks of life campaigning with ingenuity, determination, violence and occasional hilarity. For the du Maurier girls, growing up surrounded by beautiful actresses and make-believe, it was hard to comprehend that women would rebel against the status quo. More distant still was the thought that women’s work could be dirty, gruelling and dangerous – and essential to the nation’s efforts, not just in the factories but also at the front line as nurses and ambulance drivers. Mrs Pankhurst had even suggested that women could be trained up as a fighting force, as they were in Russia. She saw women taking their full part in all aspects of war as strengthening her call for women’s vote.

Most privileged middle-class girls of the time were shielded from the worst horrors of the war, but for the du Maurier sisters their retreat from school not only limited their contact with the wider world, it also meant their narrow view of what it was to be a woman remained unchallenged. Beauty, fine manners and charm were prerequisites, as demanded by their father and embodied in their mother, regardless of what darkness or mutiny went on beneath the surface. The lack of an independent school life with friends and exposure to different perspectives meant the overwhelming influence on the sisters’ thinking and opinions came from their reading, their imaginations and their parents – and the du Maurier parents were more influential and odder than most.

As an Edwardian father, Gerald set the family’s ethos and was opinionated and melodramatic in the expression of his views. Fascinating and contradictory, he was terrified of boredom yet easily bored, seeking distraction in other people and gossip. Extravagant in most things and a natural show-off, he was ever fearful of stillness and introspection. He was a physically elegant man, not tall, but slightly built with a large head and raw-boned features in a highly expressive face. Witty, light-hearted and terrific company, Gerald so often played the joker in the pack. Roger Eckersley, the genial Director of Programmes at the BBC, was struck by his subversive energy: ‘I have seldom met anyone more bubbling over with the absurdist nonsense than [him].’5 But Gerald would as easily swing into depression and self-pity when nothing seemed to be right, and he could be as petulant as a spoilt child.

Greatly fond and easy-going with his children, Gerald alternated between laxity and ridiculous strictness. Angela thought him ‘a strange father because in a lot of ways he was much more like a brother, but he could be very difficult’.6 What she found problematic was how, on occasions, he became an emotional bully: possessive and intrusive in their lives, unaware of the pernicious effects of his blundering comments and flippant ridicule. She recalled a story of how her father had often had flaming rows round the dining table with one of his sisters, probably Aunt May, and on one occasion, when she burst into tears, he had shouted after her as she left the room ‘that she was “a barren bitch”’.7 He appeared to get away with this kind of cruelty. Aunt May had indeed wanted children but not managed to have them. Their father George had only gently remonstrated with Gerald over his comment, and then rewarded him with a wink. Evidently, Gerald was still the indulged youngest child. The kindly husband of his humiliated sister could only manage a startled clearing of the throat.

His daughters liked to remember their father more as a Peter Pan than a Captain Hook. He entered their games with gusto, playing cricket on the lawn and teaching Daphne and Jeanne to box by tapping each other on the nose. As an atheist he gave his daughters no formal religious education, but he was however sentimental and superstitious. He did not rate modern art or music, even though Millais and Whistler had been some of his father’s closest friends. He hated and feared homosexuality, despite many in his profession and among his friends being quite clearly sexually unconventional.

All these strongly held opinions were absorbed by the sisters. One of the contradictions most difficult for them to integrate into their own social behaviour was exhibited daily by Gerald. He was courteous and charming to a fault to everyone he met, from strangers to his closest associates, but mocked and mimicked them when their backs were turned. One of the most important lessons inculcated into the sisters was the necessity of social grace and politeness at all times. The contradiction of being expected by their father to curtsey sweetly to his friends was hard to reconcile with the encouragement to ridicule them once they had gone. Such double standards were confusing. It was hard for a child to fathom what was real in love and friendship if it all appeared to be a sham.

The mockery was often fond, aimed at his closest friends, and bonded him with his audience of admiring daughters. But it also encouraged a sense of superiority, setting them apart from the mocked, making it difficult to empathise or be intimate with someone reduced to a caricature. The du Maurier family language, wonderfully visual and effective with distinctive words and phrases practised by Gerald and expanded by his children, entertained and strengthened the sense of tribal feeling. It also excluded outsiders and reinforced the family’s separateness. The writer Oriel Malet, who became a great friend of Daphne’s in her middle age and then of Daphne’s daughter Flavia, recalled how the coded language, colourful and intriguing as it was, could make one feel a foreigner among friends.

Daphne in her 1949 novel, The Parasites, evoked brilliantly the theatricality of the sisters’ childhood that set them apart, describing how disconcerting the fictional Delaney (and du Maurier) children could be:

[Maria] had the uncanny knack of exaggerating some little fault or idiosyncrasy … and her unfortunate victim would be aware of this, aware of Maria’s large blue eyes that looked so innocent, so full of dreams, and which were in reality pondering diabolical mischief … [Niall]’s silence was full of meaning. The grown-up individual meeting him for the first time would feel summed-up and judged, and definitely discarded. Glances would pass between Niall and Maria to show that this was so, and later, not even out of earshot, would come the sounds of ridicule and laughter.8

Unusual for his generation, Gerald enjoyed his daughters’ company and this intimacy meant his influence on their growing minds was all the more powerful and potentially malign. Unusually for any generation, Gerald confided his romantic entanglements with young actresses to Angela and Daphne and made an entertainment of it, inviting them to scoff at the young women’s naivety and misplaced hopes, and compromising the sisters’ natural loyalty to their mother, who was not included in these confidences. These young actresses were nicknamed ‘the stable’ by his daughters, who were encouraged to think of them as fillies in a race for the prize of their father’s attentions. His daughters ‘would jeer, “And what’s the form this week? I’m not going to back [Miss X] much longer”,’9 and they laughed as their father brilliantly mimicked the voices and mannerisms of the poor deluded girls.

These conversations made them feel uneasy though. Their father was positively Victorian in his attitudes to his own daughters’ morals: he was pathologically suspicious of any male with whom they socialised, implying that something dreadful lurked behind the friendly wave or kiss on the cheek, and did not want them to grow up. Angela found his intrusiveness hard to bear. As a young woman returning from a party, she would see him peering from the landing window: ‘“Who brought you home?” he would say, if the chauffeur had not collected us. “Did he kiss you?” he would ask. Absolutely frightful. He was easily shocked.’10 He darkly threatened that they would ‘lose their bloom’, which suggested to them that a young man’s kiss somehow tarnished their looks, that the rot would set in, making their corruption visible to all. Angela concluded her father would have been happiest if his daughters had been nuns, with Cannon Hall as the nunnery.

Yet Gerald’s own behaviour belonged more to the Restoration age where self-indulgence and the desperate desire for distraction cast constraint to the winds. Angela was confused and scared by her father’s sexual hypocrisy. Daphne, wary of adults and suspicious of their motives, perhaps grew even less inclined to look to conventional love and marriage as the path to happiness, with the example of her own adored father before her. In her teenage diary she wrote, ‘I suddenly thought how awful just being married would be. I should be so afraid, so terribly afraid, but of what? I don’t know.’11

Jeanne was still young and protected by her mother’s love and less susceptible to her father’s charm. She spent much more time with Muriel and was a sweet-natured child who was musical and good at drawing and looked most like her mother. But all the sisters, such close companions in their games and make-believe yet temperamentally so unalike, were bound with family pride and affection. They shared too a taboo on discussing with adults the things that really mattered.

Their father had been spoilt and adored by women all his life, first his mother and elder sisters, now his wife and daughters, and the actresses who depended on him for their careers. A young John Gielgud was struck by Gerald’s gift for getting what he needed from others: ‘He was a very great director, particularly of women. He was a great fancier of pretty women, and he taught them brilliantly, but very often they were never heard of again.’12 Taken up and dropped, these young women never ruffled the surface calm of his wife who had become, in effect, a second mother to him. Even Muriel’s unmarried sister Billy devoted herself to Gerald in the role of personal secretary and made her life’s work his every ease and comfort. Nobody challenged him or called his bluff. He was the grand panjandrum of his universe, but fundamentally weak and dependent on a constant flow of feminine admiration and solicitude. In order to maintain this life-giving stream, he had become adept at making himself as irresistibly charming and seductive as he could. And his daughters were as much ensnared as anyone.

If their mother Muriel had been more of a presence in the older daughters’ lives, she might have added a creative counterbalance to Gerald’s powerful influence. Strikingly attractive all her life, with fine manners and surface charm, her absorption in Gerald’s life and career meant her true character was somehow effaced, leaving just a sense of chilly detachment and inner steel. Only Jeanne received the unconditional love that was left after Gerald’s needs and demands had been answered. ‘He was her whole life,’ Daphne recalled, ‘and next to D[addy] came Jeanne, petted and adored though never spoilt, while Angela and I … came off second-best.’13

In fact, Angela came off worst of all, as, after Nanny left, she was special to nobody and was hungry for approval and affection. Very early she recognised that in her family she was considered plain and had therefore failed the most important test of womanhood. Her need for notice and love found expression in hero-worshipping men and women alike, so much so that her father teased her mercilessly for her swooning expression. ‘Puffin with her swollen look,’ he would say in a not entirely affectionate way. It was partly his manner, his need to be funny and make people laugh, but there was also an element in that phrase of exasperation that his eldest daughter was slightly plump, too earnest to be cute, and not the refined beauty she ought to have been.

Daphne was clear-eyed about Gerald’s lack of sensitivity to his family, describing how at the theatre he was careful not to hurt anyone’s feelings but was ‘constantly tactless and continually thoughtless in private life’.14 From this jest about Angela’s looks, reiterated many times, came the family nickname that would accompany her through life, Puffin, Puff, Piffy. She tried to be a good sport and see her father’s comment as a trifle, something amusing, but years later was moved to write: ‘DON’T always tease your children when they fall in love, it can be dangerous’. Eventually Angela grew resigned to her family’s insensitivity, admitting bleakly that by the age of sixteen she knew, ‘if one couldn’t be the beauty one might as well be the butt’.15

For good and ill, Daphne was the daughter most affected by Gerald’s peculiarly narcissistic character. She had been chosen as his favourite at a young age perhaps because she was the most beautiful, perhaps the one most closely resembling his longed-for son, perhaps because she reminded him of his father. She alone saw through his charming gay exterior to the uncertain, dark and flawed human being within, and yet still loved him; that might have been the most compelling reason of all. The historian A. L. Rowse, who became a good friend in Daphne’s middle age, suspected that her relationship with her father haunted her adult emotional life.16 What was problematic was not Daphne’s love for Gerald so much as his cloying yet controlling need of her.

Her remarkable third novel, The Progress of Julius, written when she was only twenty-four, explores a pathological obsession of a father for his daughter. Julius has some of the overbearing yet mercurial qualities that made Gerald irresistible to his daughter. His intensity and high emotionalism (she feared he was always acting and so could never be sure what he really felt) made her own inchoate emotions oscillate between ecstasy and despair. In an extraordinary passage in the novel she conjures up something of this oppressive power that borders on psychological abuse:

[She was] aware of Papa who watched her, Papa who smiled at her, Papa who played her on a thousand strings, she danced to his tune like a doll on wires – Papa who harped at her and would not let her be. He was cruel, he was relentless, he was like some oppressive, suffocating power that stifled her and could not be warded off … she was like a child stuffed with sweets cloying and rich; they were rammed down her throat and into her belly, filling her, exhausting her, making her a drum of excitement and anguish and emotion that was gripping in its savage intensity. It was too much for her, too strong.17

Gerald’s adult neediness extended to her was far too weighty for her childlike, uncomprehending heart.

Overarching it all was his manipulative favouritism that tainted all other relationships within the family. The close emotional connection that grew between them disturbed Daphne and inevitably unsettled her mother. Musing on why there was such a mutual wariness between her and Muriel, Daphne wondered, ‘could it be that, totally unconscious of the fact, she resented the ever-growing bond and affection between D and myself?’18 Again in Julius, she explores this tragic transference to melodramatic effect. Not only did the intense Electral bond between Daphne and her father distress her mother, it inevitably unbalanced the family dynamic between the sisters.

It was Angela who felt most acutely the lack of admiration: the spotlight that might have fallen on her for a while, as the eldest, always seemed to swerve off towards Daphne. It was not her younger sister’s fault, Daphne did not seek it and in fact the limelight made her uneasy, but her beauty and detachment seemed to draw people’s attention in a way that Angela’s expressive eagerness to please did not.

The huge painting of the three sisters, executed in 1918 by the society artist Frederic Whiting, and exhibited to acclaim, epitomised the shift in power between the sisters. Angela was fourteen and feeling her way tentatively towards a sense of herself in the world. Much as she had feared growing up, she was beginning to see there were some advantages. This painting captured her on the cusp of womanhood but reduced to a rather big child. She hated the pose she was expected to hold, unflatteringly dressed in baggy clothes, sitting uncomfortably with her rump to the viewer and all her weight on one hand. She resented how she was encumbered for all time with a shiny red nose, quite possibly the result of the crying fit when she had been told that she would have to spend the whole Sunday posing in Whiting’s studio. The unfairness of this representation of her she felt was made more stark by the way Daphne was portrayed. Placed apart from the undistinguished bundle of Jeanne and Angela and Brutus the dog, she stood as straight and noble as an arrow with a visionary spark in her eyes. Every time she saw the painting Angela was reminded of this memorial to her eclipse. ‘I realised I should be handed down to posterity with a flaming shining nose, and Daphne looking rather like a flaming shining Jeanne d’Arc.’19

At about the time this group portrait was painted, Angela was ‘suicidally inclined for Love’ and her gaze fell on a young soldier who put up with her devotion, mailing her a box of chocolates from Paris that filled her with excitement. To Angela’s overactive imagination he was, ‘Apollo, Mars, God, Romance, IT’. On the one occasion she got to accompany him, Muriel insisted Daphne should go too. Their destination was the Military Tournament at Olympia in West London. In a fever of anticipation Angela carefully chose something grown-up to wear a pretty pink dress with a lowish neckline, but her mother immediately ordered her upstairs to change into a frock that matched the one Daphne was wearing. Her sister was still as slim as a sapling, and Angela felt humiliated, stuffed into the childish mauve dress that did not suit her, the linen too tight across the bust. Tears of frustration and disappointment welled in her eyes. ‘Daphne looked a dream as always, and by the time my swain had called to take us to Olympia I was red-nosed with heat, discomfort, mortification and a fit of the sulks.’20

This god-like being was a young cadet who was training alongside her father. In what appeared to be an odd caprice, with more than an element of despair to it, Gerald had decided in the last year of the Great War to enlist in the Irish Guards. His restlessness and growing sense of futility, together with the long shadow of his hero-brother Guy, made him long to prove he was more than just the ephemeral entertainer. He was forty-five and had lived the last two decades of his life as a successful, pampered thespian, chauffeured around, clad in the most luxurious clothes and fed on the best foods and wine. Daphne understood his despair. ‘He was nothing but a mummer, a trickster, playing antics in some disguise before a crowd. All he had won was a cheap popularity, and what good was that to him or the world?’21 He had just pulled off one of his greatest theatrical successes, a new production of J. M. Barrie’s play Dear Brutus, where night after night he received the audience’s ovations. The play’s conceit – whether, if we could return to something deeply regretted in our past and choose a different path, it would change anything – suffused his thinking, for he always lived his character for the duration of a play. Would life have been more satisfactory if he had taken the more difficult road?

There was a kind of bathetic heroism in Gerald’s turning his back on his glittering London life to go to training barracks in Bushey, where even the officers bawling at him were young enough to be his sons. Never the most physically or mentally robust of men, he had to submit to the gruelling training and spartan conditions alongside boys who were straight out of school. Removed from home comforts and denied the reassuring balm of his wife’s and friends’ concern, he had only the rough camaraderie of men to sustain him. Muriel moved the whole household to Bushey to be close to him. Angela explained her mother’s blinkered focus on Gerald:

My mother, for whom wars only meant parting her from her family (me at my school in Wimbledon, and now my father) one day met the famous actress and beauty Lily Elsie in Piccadilly and burst into tears with the remark, ‘Poor Gerald has gone to Bushey.’ Elsie’s husband was in the thick of the fighting but she was sympathetically full of horror for poor Gerald’s plight.22

Although Muriel had done her best to remain close to him, Gerald could only escape infrequently to eat big teas surrounded once again by his womenfolk. Angela remembered how his face had ‘an abject hungry misery’.23 It was a nightmare from which he was luckily awoken by the Armistice. He could return home having not encountered any of the fighting, but perhaps feeling some kind of personal honour had been satisfied. The play he had left behind centred on two unhappy people, mired in misery, being given a second chance of a life different from the one each had chosen, but realising it was better to just get on and live. Perhaps Gerald returned to his life in the theatre relieved at the choices he had made, and ready for the next project.

1918 was also the year when the girls’ patchy education was taken in hand by a dynamic new force. Miss Maud Waddell came into their lives to tutor them in every subject, although history was the universal favourite. Miss Waddell was quickly nicknamed Tod, as a partial rhyme on her surname, or a nod to Beatrix Potter’s Mr Tod, a wily, tweed-jacketed fox. Born in 1887, she was ten years younger than their mother and a completely different kind of woman. Miss Waddell was well educated, adventurous and independent minded, with a wealth of exotic stories of her past to tell. Before she ended up in Hampstead she had already tutored the grandson of Belgium’s Minister for Finance. She had enjoyed living with the family in the beautiful Château de la Fraineuse at Spa, inspired by Marie Antoinette’s Petit Trianon at Versailles. The Kaiser then had appropriated it and had a bedroom for himself redecorated in pink silk.

Tod became important to all the du Maurier girls, but particularly to eleven-year-old Daphne. She quickly recognised her as someone in whom she could trust and confide, a woman who filled part of the vacuum left by her mother’s emotional absence, but also a woman who responded to her intellectual curiosity and creative mind. Daphne liked to think of Tod as one of her heroines, Queen Elizabeth I. In an early letter she wrote to her:

Divine Gloriana,

Why look so coldly on your slave who adores you? Have you no commpasion on the billets written with the blood of my heart (jolly good).24

Tod responded to this clever, imaginative child (so ill-schooled that her spelling and wayward punctuation kept Tod awake at night) and understood the yearning in Daphne for something beyond the ordinary: ‘That something that is somewhere, you know; you feel it and you miss it, and it beckons to you and you cant reach it. It is’nt Love I’m sure … I don’t think anyone can find it on this earth.’ This longing for the unattainable owed something perhaps to Barrie’s Neverland that entranced the sisters’ childhoods. Daphne told Tod she was the only person to whom she could express her confused feelings, having been silenced on the things that mattered most to her by her family’s mockery and lack of understanding. Although Angela, and occasionally Jeanne, wrote to Tod also, the only letters the governess kept were those written by Daphne, in what became a lifelong correspondence full of frankness and humour. Tod later told a reporter on the Australian Argus that Daphne was ‘the most beautiful human being I have ever seen’.25 An intelligent, feeling woman who never married, Tod was to love her all her life.

Angela had endured one last experiment with formal schooling that had failed dismally. Gerald had accompanied his nephew Michael Llewelyn Davies to visit a friend of his, Eiluned Lewis, at Levana School in Wimbledon. Eiluned was a clever girl, four years older than Angela, who became a successful journalist, novelist and poet. Whether Gerald was impressed by her or the school, he determined to send Angela to the school as a boarder. Angela was fourteen and although she made some friends she was so desperately homesick she only lasted half a term, and was soon back at Cannon Hall. Tod then became responsible for educating all three girls.

Although she would remain committed to the du Mauriers, Miss Waddell for a while had other adventures to pursue. Soon after her stint tutoring the sisters she headed off in 1923 to Constantinople to teach the Sultan’s son English. This was a fascinating time for an Englishwoman in Turkey, just after the last of the Allied troops had left Constantinople, having been in occupation since the end of the First World War. Tod lived in the magnificent Dolmabahçe Palace in great splendour but did not think much of the Turks themselves. ‘What an unprogressive, aggravating people they are,’ she told the same Australian reporter. She thought them a nation lost in passive contemplation and her no-nonsense Cumbrian self wanted to pinch them awake from their reveries.26 Maud Waddell then sailed for Australia in 1926, where her brilliant mathematician sister Winnie had emigrated, eventually rewarded with an MBE for her pioneering work establishing wild flower sanctuaries. For a while Maud thought she might stay, teaching in the Outback, but finding it ‘too rough and windy’27 returned to England. There, after more, but less exciting, adventures, she eventually ended up tutoring Daphne’s children in Cornwall at Menabilly.

The du Maurier family’s move to Hampstead had been an emotional return for Gerald to the place of his childhood where he had been happiest. Restless and increasingly dissatisfied with his working life, and missing the close bond with parents and sisters, for all except May were now dead, he began to revisit the past, recalling his youth with fond nostalgia. He had always idealised his father George and the bohemian life he lived with family and artist friends, but now that he had returned to his father’s old stamping grounds the obsession with him grew. He shared his romantic reminiscences with his daughters, taking them to gaze at the old family home, New Grove House, where he had hoped to live with his own family but had had to settle for Cannon Hall instead. He would point out the studio window at which his father had once worked and then walk them up to Hampstead Heath to a twisted branch where he sat as a boy, imagining it was his armchair. The girls would climb in too, and think of their father as a boy. Then up the hill to Whitestone Pond where George du Maurier, weak-sighted and kind-hearted, had noticed a dog splashing about and plunged in, intent on rescue. But the dog was swimming not drowning. The girls then learnt how the great man, dripping wet and slightly foolish, was tipped by the dog’s owner for his trouble.

As Gerald walked them through his romance of boyhood, his daughters grew more interested in the grandfather they had never known and who, in dying before Angela was born, had been ignorant even of their existence. They had seen the leather-bound copies of Punch, with George’s elegant witty drawings, and had not thought much about the artist who had made them; but through their father’s memories they began to discover a man who was important in their own stories, whose life belonged with theirs. His novels exerted the greatest imaginative pull, most importantly Peter Ibbetson, with its compelling central theme that people can exist in a world they had purposefully dreamed. They could meet others there, possessed also of the gift for ‘dreaming true’ that joined them in this extra dimension, brought into being through will and emotion. The love story between Peter and his childhood sweetheart, the Duchess of Towers, conducted in this dreamscape, freed from conventional restraints of time and space, fuelled the imaginations of his two elder granddaughters. It was a powerful idea that offered whatever the dreamer most desired: escape and adventure for Daphne; love and romance for Angela.

At about the age of thirteen Daphne’s desire for escape from impending womanhood, and all the attendant embarrassments and constraints, caused her to dream up a boyish alter ego: Eric Avon. In real life she had been taken aside by Muriel and warned of the advent of menstruation, a rubicon that would unite her to her mother and the female half of experience and separate her, it seemed, from everything she valued and held dear. Nothing was explained to the horrified and bemused girl, only that she would bleed, and with it came confusing intimations of illness, incapacity, secrecy and shame. Just as Angela had been forbidden to mention the facts of life to her friends or younger sisters, so Daphne too was told not to discuss with anyone this looming threat to her freedom and integrity.

Eric Avon sprang to her aid. He was the imaginary personification of the boy she should have been, the embodiment of uncomplicated male energy, the son for whom her father had longed. He was sporty and brave, captain of cricket at Rugby School, and his day of glory came each year at the imaginary cricket match between Rugby and Marlborough School, played out in the garden at Cannon Hall. Jeanne and her friend Nan were drawn into this fantasy. Renamed David and Dick, the Dampier brothers, they bowled and batted for Marlborough, the opposing team, and invariably lost to the one-man sporting hero, Daphne in her role as Eric Avon. Angela and Tod were roped in as spectators to clap politely from the sidelines.

Daphne inhabited the persona of Eric Avon for more than two years. Only once she had turned fifteen (and Eric turned eighteen) did she have him play his last triumphant cricket match, for he would have to leave Rugby for Cambridge University the following autumn. Daphne walked into the lower part of the garden at Cannon Hall, scene of so many of Eric’s triumphs. ‘He wept. The moment of sadness was intolerable. Then someone from the house called “Daphne!” and it was all over. Eric Avon had left Rugby School for ever.’28 This had so much of the emotional force of Peter Pan, where Peter angrily repels any suggestion he might grow up and become human, the whole play suffused with sadness at what is lost when childhood is left behind.

Years later, Daphne recognised that Eric Avon became submerged in her subconscious and never really left her, emerging in various guises as her inadequate male protagonists in I’ll Never Be Young Again, My Cousin Rachel, The Scapegoat, The Flight of the Falcon, and The House on the Strand. Although they were weak while Eric, like Daphne herself and many of her fictional heroines, were resolute and self-sufficient, these men relied on strong male mentors, perhaps echoing something of her father’s relationship with Tom Vaughan, his supremely capable and efficient business partner, or with his competent and heroic elder brother. Tom Vaughan was a remarkably successful man and central to the functioning of the du Maurier household. He managed Wyndham’s Theatre with great creative and professional acumen, and fixed all the family’s financial and practical problems too. Angela appreciated how crucial he was to everything. ‘That the du Mauriers could get on without Tom Vaughan seemed an impossibility. Alas, when he died it became all too evident that life without him was a sadly complicated affair.’29

The intolerable sadness felt by Daphne/Eric in the garden the day of the last cricket match was the realisation that she could not remain this boyish child for ever. At fifteen she was aware of Angela on the verge of ‘coming out’ and having to enter the dreaded social whirl. The expectations of family and society would hedge Daphne in too. Perhaps the prospect of her growing up caused her father unease as well for, about the time that puberty and Eric Avon arrived in her life, he wrote Daphne a remarkable poem, celebrating her as the Eternal Girl, yet recognising her own, and his, disappointment that she was not that longed-for boy:

My very slender one

So brave of heart, but delicate of will,

So careful not to wound, never kill,

My tender one –

Who seems to live in Kingdoms all her own

In realms of joy

Where heroes young and old

In climates hot and cold

Do deeds of daring and much fame

And she knows she could do the same

If only she’d been born a boy.

And sometimes in the silence of the night

I wake and think perhaps my darling’s right

And that she should have been,

And, if I’d had my way,

She would have been, a boy.

My very slender one

So feminine and fair, so fresh and sweet,

So full of fun and womanly deceit.

My tender one

Who seems to dream her life away alone.

A dainty girl

But always well attired

And loves to be admired

Where ever she may be, and wants

To be the being who enchants

Because she has been born a girl.

And sometimes in the turmoil of the day

I pause, and think my darling may

Be one of those who will

For good or ill

Remain a girl for ever and be still

A Girl.

This was a poem full of complex meaning when written by an adored and influential father for his favourite daughter. Daphne stood on the threshold of adulthood, confused by her identity and struggling to find a sense of herself in the world. Gerald’s elegiac words could only compound that confusion. He regretted the son that might have been, and celebrated the lovely daughter whose gender made her second best. But she was lovely only as long as she remained a girl and managed somehow not to grow to womanhood. Becoming a woman meant losing so much of value: joy in action, beauty of form, simplicity, freedom, integrity of the self.

At a time when women had been risking their lives in wars abroad, and at home taken on the Establishment and won the first concessions in their battle for the vote, Gerald’s view of the roles of men and women was old-fashioned and stultifying. In the poem Daphne as a boy is full of action, a hero figure, ‘brave of heart’ and spurred to ‘deeds of daring and much fame’. On the other hand, her place in the world as a girl is passive, her looks and the effects she has on others paramount – ‘so fresh and sweet’, prone to ‘womanly deceit’, ‘dainty’ and ‘well attired’. Muriel was the role model for this kind of woman, and Daphne did not want to be like her at all.

Daphne and Jeanne were happiest in boy’s shorts, thick socks and stout shoes. They did not care about their hair or the grime on their faces. Daphne hated her white knees after a winter of being covered up and would rub dirt into them each spring to reclaim her tomboy self. Their prettiness belied the masculine characters that swaggered in their imaginations and peopled their games. The stereotypical sporting hero Eric Avon was not based on the kind of men who loomed largest in their lives like their father and the romanticised view of their grandfather. These immensely successful men were artists and darlings of the drawing room, not men made on the sports field or battleground. In fact, George in later life had lost much of his sight and was in thrall to his womenfolk, and Gerald’s love of gossip about friends’ private lives, tireless practical joking, and enjoyment of the company of women made him an exceptional entertainer with an effete and dandified air, rather than an all-conquering hero. His propensity to go to pieces if separated for too long from Muriel also disqualified him from the square-jawed masculine ideal. In the du Maurier household, where the women were capable and robust and the men were pampered and indulged, sexual stereotypes were not the norm.

Unlike her sisters, Angela did not want to be a boy. She was happy enough to be a girl even though she bitterly regretted she was not beautiful and therefore felt handicapped in the great marriage game that her family considered a woman’s natural destiny. She too was afraid of growing up, but it was her emotionalism that bothered her, the embarrassment of her crushes and the torrent of feeling that they unleashed. The young Angela was sensitive and serious and hated being teased, the default position in her family. She was also ignorant and afraid of the sexual male, that scary other that had grown sinister in her imagination as a result of early shocks and her inadequate education:

The business of growing older, into ‘double figures’, I disliked. I was unhappy when I was told I was too old to wear my nice white socks in the summertime, and made to wear horrible brown stockings … one was a fish out of water, too young to listen to sophisticated conversation, at the same time not wishing to play cricket on the lawn with younger sisters and their friends … pulled both ways, misunderstood at times by young and old alike, and not always understanding oneself.30

Angela’s literalness of mind and the inadvertent hurt caused by adults who did not understand was illustrated by an unhappy infatuation she never forgot. At weekends, Cannon Hall was filled with various stage people: one Sunday, even Rudolph Valentino came to lunch, to general excitement, as too did Gary Cooper, the embodiment of Hollywood star power. There were the long-established acting friends like Gladys Cooper, Viola Tree and John Barrymore, and any number of glamorous others who passed through their lives. But in 1919, when Angela was fifteen, she was taken by her parents to see a magnificent production of Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac. Robert Loraine – ‘Bobby’ to them all – was playing the title role. From then on Angela was smitten. Only three years younger than Gerald du Maurier, he was an actor-manager like him and the theatre he successfully managed was the Criterion. A fine actor, he was usually cast as the romantic lead, and even went on to tackle Shakespeare. But he was much more than this, a true heroic figure. A pioneering aviator, he had only just survived as a flying ace in the Great War and been decorated for his bravery with an MC and DSO. Angela had a photograph of him in his Royal Flying Corps uniform and she kissed it every night, along with her picture of the Prince of Wales.

Bobby had a mellifluous voice and it amused him to spout the most rousing bits of Shakespeare under Angela’s bedroom window at night. Inevitably, Angela, by now sixteen, began to dream of marrying him. The age gap seemed no barrier: perhaps the fact that he was her father’s generation was a reassurance to her. Then with the thoughtlessness of adulthood, Bobby hijacked her fantasy by casually saying to Gerald at one of their family Sunday lunches at Cannon Hall, ‘the day will come I expect when I shall ask you for Angela’s hand’. Given her youth, innocence and supercharged romantic nature, it was not unreasonable of her to imagine the deed was done and she would be the next Mrs Robert Loraine, with accompanying beautiful house, enchanting children, dogs, the whole caboodle. (She admitted she daydreamed about weddings and babies’ names, without sex coming into any of this at all.) But Angela had misunderstood Bobby’s manly banter with her father, and he had misunderstood how serious she was and how tender her heart. ‘The day never came, and he suddenly appeared with an exquisite wife very little older than me (which made one’s frustrated misery more acute).’31 It may have been on this occasion that Angela, in the depths of despair and with pure melodrama running in her veins, had jumped up onto a wall running along the Embankment, declaring she would cast herself into the Thames. Luckily she was with the imperturbable Tod who replied, ‘Not now, dear, it’s teatime.’32

The sisters, unable to confide in their parents, turned to each other. Daphne, struggling with deeper existential questions, turned to Tod. Their exasperated mother would complain that she could never get one sister to side with her against another as they always stood up for each other. Angela was incapable of keeping her tumultuous emotions to herself and so Daphne, already a confidante, was party to all her upset and disappointment. Daphne at thirteen had just sought refuge from the adult world in the creation of her boy-self Eric; no wonder that she retreated further when she observed the incomprehensible behaviour towards women of even the nicest men. Her body may have betrayed her by beginning to turn her into a woman, but her diary for that year was still childlike, full of cricket matches and the birthday party she gave for her teddy bear. Jeanne at nine, the favoured companion of their mother, was very much the baby and sheltered from even this incursion of the adult world.

The following summer Angela would see her longing for love thwarted at every turn while her younger sister, without seeking it, once again became effortlessly the centre of admiration and, this time, of male desire. In the middle of the family seaside holiday, fourteen-year-old Daphne glanced up from paddling and shrimping to find her much older cousin, Geoffrey, looking at her with a strange smile. Something about the smile caught the girl’s attention and made her heart beat faster. She had never felt this way before. She smiled back. She knew nothing of the facts of life and was completely uninterested in the mechanics of sex and would remain so, she recalled, until she was eighteen. But in that one moment, Daphne’s innocent world of cricket and reading and making up stories was intruded on by a grown-up male old enough to be her father.

It was 1921 and the du Mauriers had rented a house in Thurlestone in south Devon, and as usual other guests had been asked to join them. Cousin Geoffrey, the elder brother of Gerald Millar, who had so appealed to Angela when she was younger, was divorced from his first wife. This had caused a scandal amongst the aunts and uncles who considered divorce something that should never happen in a family like theirs; ‘one might have thought a national calamity was about to occur’.33 This raffishly good-looking thirty-six-year-old actor had subsequently remarried and had brought his second wife with him on this visit to his cousins. But his roving eye had been caught by the attractive sight of his young cousin paddling in the sea, still so obviously just a pretty child but on the threshold of sexual awakening, and he smiled.

Daphne never forgot the peculiar excitement caused by that secret smile. She could not understand it but liked the physical sensation and the sense that she was special and there was a precious understanding between them. When all the children were sunbathing on the lawn, with rugs over their knees, Geoffrey came and lay beside her and under the blanket reached for her hand. The effect on her was electrifying and unsettling; something dormant was awoken in her. ‘No kisses. No hint of the sexual impulse he undoubtedly felt and indeed admitted … but instead, on my part at least, a reaching out for a relationship that was curiously akin to what I felt for D[addy].’ Daphne found this frisson with Geoffrey even more exciting because it was wrong and especially because it was secret, hidden from her pathologically possessive and suspicious father and right under the nose of Geoffrey’s unsuspecting wife. ‘Nothing, in a life of seventy years, has ever surpassed that first awakening of an instinct within myself. The touch of that hand on mine. And the instinctive knowledge that nobody must know.’34

Geoffrey’s behaviour could be seen as a subtle seduction by a much older, worldly-wise man of a vulnerable cousin, still a child who should have been safe in his company. In a classic ploy of the seducer, he told her he had already grown disenchanted with his new wife and now, because of his feelings for Daphne, no longer wished to go on tour to America at the end of the year. There was little doubt that the whole flirtation that summer was a deliberate manipulation of a young girl’s emotions to gratify his egotistical needs. The loading of responsibility for his dubious behaviour on her child’s shoulders was cowardly, and distorted her sense of power and integrity. The intrusion of a confusing adult world into her child’s one, lived largely in the imagination, certainly unsettled Daphne and absorbed much of her thoughts for the rest of the year, uniting her to him in an indissoluble bond of rebellious conspiracy that was to last a lifetime. Daphne loved to think of herself as daring and she also enjoyed a growing sense of the power she had over others. Neither was she averse to causing her father anxiety and jealousy – it all reinforced her central importance in his life.

Her recognition of the similarity of the feelings she felt for Geoffrey and those for her own father informs one of the enduring themes of her fiction: that of incest and taboo. But for Daphne, always living more vividly in the mind than the body, the idea of incest would come to exert an intellectual fascination that grew, she explained, from her realisation that we are attracted to people who are familiar to us, that family provide the real romance of life.

Years after the encounter in south Devon, when she was twenty-one and her obsession with Geoffrey had cooled to an amused flirtatious affection – although he remained as smitten with her as ever – she had fun teasing him by meeting him in the drawing room at Cannon Hall to say goodnight, dressed only in her pyjamas. With her parents in bed on the floor above, she allowed him passionately to kiss her for the first – and last – time. Having not been kissed by a man before, apart from her father, she found it ‘nice and pleasant’, but, with a startling lack of understanding of human sexuality and empathy for the feelings of another, wished Geoffrey could be more light-hearted. He had finally managed some intimacy after years of secretive smiling, furtive knee-stroking and hand-holding, with the object of his forbidden desire prancing about in her pyjamas, at night, and she complained he was rather overexcited.

‘Men are so odd,’ she wrote in her diary, ‘it would be awful if he got properly keyed-up.’35 Daphne added another peculiarly detached statement: ‘He is very sweet and lovable. The strange thing is [kissing Geoffrey] is so like kissing D[addy],’ and went on to surmise that perhaps their family was like the incestuous Borgias, with her as the fatally attractive Lucretia. But then this was a girl who liked to shock and given how underwhelmed she was by Geoffrey’s kisses, likening them to Daddy’s did not suggest unbridled fatherly or daughterly passion. Any incestuous impulse between father and daughter was more likely to reside in his overbearing emotional demands on her and her answering fascination with him, united with resentment and excitement at how important she was to him. The growing realisation of her power over others through her attractiveness and detachment was thrilling.

While Daphne, only just into her teens, was quickening their cousin’s pulse simply by being there, Angela recalled yet another example of her own lack of beauty and physical presence. She was seventeen when she accompanied her ten-year-old sister Jeanne to a children’s party in a grand house in London. Dressed in a sober blue coat and skirt, and feeling rather overweight and shy, she was mistaken by the butler for a children’s nurse and shepherded in with the other visiting servants. But ‘the nurses were far too high and mighty to bother with me’,36 and, although short and appearing younger than her age, Angela was not about to become one of the children for the afternoon, so she sat in lonely exile for hours until the party was over and she could escort Jeanne home. She made a joke of it, but these humiliations and unflattering comparisons undermined the self-esteem of a young woman who already felt inadequate and in some fundamental way unworthy of love.

The summer of 1921 was clouded for the family by another tragedy that befell their ill-fated Llewelyn Davies cousins. The eldest of them, George, taken into the care of Uncle Jim Barrie after he was orphaned, had been killed in the war. Michael, the fourth brother, and the main inspiration for Barrie’s Peter Pan, was now twenty-one and a sensitive poetic young man, a troubled undergraduate at Oxford University. On a perfectly fine and warm afternoon in May, he and his best friend Rupert Buxton drowned together in a still bathing pool in the countryside just outside Oxford. They appeared to have died in each other’s arms, in what may have been a double suicide, but no one could be sure. Saving the families’ feelings was paramount, and the coroner declared a verdict of accidental death. But this did not soften the blow of two immensely promising young men dying in mysterious and harrowing circumstances. There is no mention as to how the du Maurier sisters took the news except for Daphne who recorded it in her diary (‘how dreadful’) along with the information that their youngest Llewelyn Davies cousin Nico came to stay before the funeral.

Contrary to some suggestions that J. M. Barrie not only ruined the boys’ lives but also had some malign hold over Daphne’s, it was noticeable that in her early diaries, when his influence was meant to have been intense, his name did not once appear. In fact the du Maurier sisters seem not to have seen very much of him or the Llewelyn Davies cousins either, once the boys’ mother had died. When Peter, the third eldest brother, came to lunch at Cannon Hall in 1925, Daphne wrote in her diary that she had not seen him for years. Barrie’s creation, Peter Pan, however, continued to hold a magnetic attraction for them all.

Holidays apart, life continued at Cannon Hall with lessons during the week, wild games for Daphne and Jeanne in the garden, and paperchases on the heath – with Daphne as the paper-scattering hare. The glamorous friends of their parents filled the house at weekends, when the du Maurier girls were expected to practise their social skills and be attendant maidens and entertainers. Both Angela and Jeanne were musical, a gift that could be traced back to the du Maurier ancestors where grandfather George and his father were known for their beautiful tenor voices which would bring an audience to tears. All three girls learned to play the piano – as well-brought-up girls did – but only Angela and Jeanne persevered into adulthood. Jeanne was particularly talented and continued to play all her life. In the du Maurier household, playing the piano was not allowed to be a private pleasure. Muriel insisted the girls play for her friends after lunch, and she refused to let them use sheet music, it all had to be from memory. This became a misery particularly for Angela who had to stumble through some standby like the Moonlight Sonata in front of a long-suffering audience, accompanied by her mother’s audible intakes of breath at every wrong note, of which there were many.

She much preferred practising with their enthusiastic music mistress, who would come to the house and inspire Angela and Jeanne to play exciting duets, the Ride of the Valkyries being one memorable favourite. In fact her visits sparked both girls’ love of music. Angela’s love of opera and of Wagner began with these lessons.

At sixteen, Angela had a good singing voice and dreamed of being an operatic diva. She had no ambitions to be an actress but longed to sing, and as nothing but the most romantic roles attracted her, she wanted to be a soprano. This proved to be difficult as she was naturally a good contralto, but Daddy was paying, so a succession of well-regarded singing teachers attempted to turn her into a less good mezzo-soprano and finally into a reedy excuse for a soprano. ‘My future at Covent Garden was soon doomed to a still-birth.’37 This frustration of a musical career was a lasting regret to her but her love of music was to last a lifetime. Ballet too was a lasting pleasure, introduced to her when she was fifteen by one of the most beautiful women in England, Lady Diana Cooper, or Lady Diana Manners as she was then, who whisked her off to the Diaghilev season at the Alhambra, a spectacular Moorish-inspired theatre dominating the east side of Leicester Square. ‘I was her slave for life,’38 was Angela’s characteristically effusive reaction to this thrilling experience.

By 1921, Jeanne was becoming more than just her mother’s pet and Daphne’s willing sidekick in her make-believe worlds. She was not only developing into a talented artist and pianist, she was also growing surprisingly good at tennis, and would soon be entering tournaments. Photographs showed this pretty girl growing into a sturdy, strong-limbed youngster whom Daphne nicknamed ‘The Madam’. She wrote to Tod that Jeanne had grown upwards and outwards: ‘her legs resemble what a stout Glaxo baby may eventually grow into, and she will probably be ten feet each way! Her taste in literature takes after Angela, she has just finished “The Great Husband Hunt”!fn1 which she gloated over.’39 Jeanne retained for many years the alternative identity of David Dampier, schoolboy sports star, given to her by Daphne. Many years later her partner in life, Noël Welch, who knew all three grown-up sisters very well, commented that Jeanne, ‘the youngest, would have made the best boy … She has never got over not being able to lower a telescope from her eye with a suitably dramatic or casual remark, her feet apart, her square shoulders, so elegant on a horse, braced against the wind.’40

In another letter, Daphne wished she could be as placid and happy as her youngest sister and was disconcerted that she felt bored with life before it had even begun. She was already writing a book about a boy called Maurice who suffered from her own sense of dislocation from humanity and who identifies with the freedom of the natural world, for trees and water and sky. The whole story is imbued with a Peter Pan-like longing for something unattainable. Even the father figure whom Maurice finds to console his widowed mother is an amalgamation of her own father and Barrie, a man who had never grown up.

After four years of tutoring the du Maurier sisters, Tod had left for Constantinople at the end of 1922. In her reluctant progress to adulthood, Daphne especially missed her sympathetic and practical approach to life. Miss Vigo had replaced her and although she lacked Tod’s personality she was a good teacher, encouraging Angela and Daphne’s writing efforts and Jeanne’s drawing. Ever inventive, Daphne, as a Christmas present for Angela, created a magazine where all the stories, news, gossip, poems and articles were as if written by ‘Dogs of Our Acquaintance’. Angela remembered it all her life as a brilliant piece of work that anyone who loved dogs, and was prone to give them individual characters and voices, would appreciate. The girls were not educated in science and barely any mathematics, but their French was passable. They were keen readers, could play the piano, and knew how to behave in polite society; like well-bred girls of their time and class they were being schooled to become good wives to well-bred men who were wealthy enough to keep them in style. Their lives would be determined and their horizons described by the men whom they married. But little did their parents know that an inchoate rebellion was already stirring in their breasts for there was not much about a woman’s life in the first decades of the twentieth century to commend itself to them. Each sister would take her destiny in her own hands: none would become the exemplary wife that their mother had so gracefully embodied.