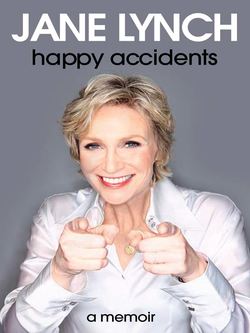

Читать книгу Happy Accidents - Jane Lynch, Jane Lynch - Страница 6

1 Pontifical

ОглавлениеIF I COULD GO BACK IN TIME AND TALK TO MY twenty-year-old self, the first thing I would say is: “Lose the perm.” Secondly I would say: “Relax. Really. Just relax. Don’t sweat it.”

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t anxious and fearful that the parade would pass me by. And I was sure there was someone or something outside of myself with all the answers. I had a driving, anxiety-filled ambition. I wanted to be a working actor so badly. I wanted to belong and feel like I was valued and seen. Well, now I am a working actor, and I guarantee you it’s not because I suffered or worried over it.

As I look back, the road to where I am today has been a series of happy accidents I was either smart or stupid enough to take advantage of. I thought I had to have a plan, a strategy. Turns out I just had to be ready and willing to take chances, look at what’s right in front of me, and put my heart into everything I do. All that anxiety and fear didn’t help, nor did it fuel anything useful. Finally releasing that worry served to get me out of my own way. So my final piece of advice to twenty-year-old me: Be easy on your sweet self. And don’t drink Miller Lite tall boys in the morning.

I DON’T KNOW WHY, BUT I WAS BORN WITH AN EXTRA helping of angst. I would love to be able to blame this on my parents, as I’m told this is good for book sales. But I can’t.

Enjoying a Very Merry Breakfast, Christmas 1980.

I grew up in a family that was pure Americana. We lived in Dolton, Illinois, one of the newly founded villages south of Chicago created to house the burgeoning middle class. We were like the subject of a Norman Rockwell painting, except it was the 1960s and ’70s, so he would have had to paint us with bell-bottoms and a stocked liquor cabinet. I didn’t settle into myself as a child, but the family I had around me was entertaining and embraced the life we had.

My dad, Frank, was a classic Irish-Catholic cutup. He was always singing a ditty, dancing a soft-shoe, or cracking wise while mixing a cocktail. He was almost bald by the time he was nineteen, and every day he’d smear Sea & Ski sun lotion on top of his naked head, then slap a little VO5 onto his hands and smooth the ring of hair around the sides with a flourish. “How do you like that?” he’d say to himself in the mirror, and sing under his breath, “I’ve got things to do, places to go, people to see.” And after that daily Sea & Ski ritual, damn if he still didn’t end up getting skin cancer on his pate. However, it would be lung cancer that took my dad from us in 2003, and I miss him every day.

I can remember my dad, when I was really young—so young, it’s like Vaseline over the memory—dancing with me in the living room. “Do you come here often?” he’d ask, twirling me around and singing along with Sid Caesar: “Pardon me miss, but I’ve never done this … with a real live girl …”

My dad also did a bang-up Bing Crosby. I loved it when he sang, and we never had to wait very long for it. He’d sing while putting sugar in his coffee, while buffing his shoes, or for no reason at all. He’d make up songs about us, the more ridiculous the better: To the tune of “Val-deri, Val-dera,” he’d sing “Janeeree, Jane-erah.” My nickname became simply Eree-Erah. He added –anikins or -erotomy to the end of anyone’s name. My older sister was Julie-anikins, my younger brother, Bob-erotomy. One of his favorite joyous exclamations was “Pon-TIFF! Pon-TIFF!” from the word “pontifical,” which was his way of saying “fabulous.” And “My cup runneth over” was boiled down to “My cup! My cup!” Speaking of cup, coffee was coffiticus, my mom was L.T. (Long Thing, because she was tall), and the phone was the telephonic communicator. We would roll our eyes or feign embarrassment—but we all wanted to be the subject of Dad’s silliness, to be a part of his joy.

The Lynch family in red, white, and blue for the 4th of July, circa 1964 (I’m on the right).

Each day, when Dad came home from his job at the bank, the first thing he’d do was put his keys and spare change into the saddlebags of the little ceramic Chihuahua that sat on his dresser. Then he and my mom would indulge in their nightly cocktail ritual with their favorite drink, Ten High Whiskey. Dad had his with ginger ale and Mom had hers with water, and they’d toast with the words “First today, badly needed.” Dad would say, “L.T., let’s get some atmosphere!” and they’d dim the lights and start singing something from My Fair Lady, Dad harmonizing perfectly to my mom’s melody.

Banks were closed on Wednesday, and my dad loved his day off. It started at Double D (Dunkin’ Donuts) because he loved their coffiticus and the chocolate cake donut. Wearing his blue elasticized “putter pants,” he would check off items on his to-do list. He was forever singing something goofy under his breath; “liver, bacon, onions …” was a favorite. He wanted us to be as enthusiastic as he was about his accomplishments. If Wednesday’s lawn work went unnoticed for its superior greenness, he’d plead, “Rave a little! Rave a little!”

Dad goes after Mom with our new electric knife.

My mom, Eileen Lynch (nee Carney), was, and still is, gorgeous. Tall and blond, with navy blue eyes and beautiful long legs, she never failed to turn heads. She always had a nice tan in the summer. And she’s a clotheshorse who never pays full price … ever … unlike her middle kid. To this day (and she is now in her eighty-second year) she puts on an outfit every morning. She’s classy down to her socks. She would kill me if she saw the comfort shoes I sneak under those long award-show gowns, especially because we have been known to watch hours and hours of What Not to Wear together. I share her love of fashion— I just don’t have her eye, or the figure to look fabulous in anything off-the-rack like she does.

Mom is half-Swedish and half-Irish, but the Swedish tends to win out. She can get sentimental, but for the most part, she’s strong and independent and doesn’t suffer fools, show-offs, or braggarts, and of course I’m nothing if not a foolish bragging show-off. Somehow, she manages to love me anyway.

But when Mom opens her mouth, she’s hilarious, though mostly she doesn’t mean to be. She’s a bit spacey, and her synapses don’t fire as fast as the rest of ours. She has always been unperturbed by her oblivion—and barely fazed when she finally gets the joke.

Her eyeglasses were always full of fingerprints, smudges, and pancake batter. I’d take them off her head, wash them with dish detergent, then put them back on. “Wow!” she’d exclaim, seeing what she had been missing.

She is absolutely frank with her opinions and literal in her interpretations. In our family she was the perfect “straight man” to the hijinks.

Our house ran like clockwork. All five of us sat down to dinner at the same time every day, after which Mom would have another cocktail, and maybe another. Dad would watch the news, and at 10 P.M. he’d eat a Hershey bar with almonds and settle in for Johnny Carson’s monologue. After that, it was time for bed.

My parents truly loved each other, and almost always got along. If you ask Mom now about their life together, the only negative comment she’d come up with is “Sometimes he’d bug me.” She had to have at least one criticism; she’s Swedish. Dad, on the other hand, had no criticism of my mother. And for a man in the sixties, my dad really got women—he understood and loved them. Once, when he had to go buy my mom Kotex at the store, the guy at the counter, embarrassed, slipped them into a paper bag. He started to carry them outside, so my dad could take the bag where no one would see, but my dad just laughed. “It’s all right,” he said. “I don’t need to sneak out the back door.”

Apparently my mother was unaware that witches don’t have vampire teeth or wear sunglasses. With Dad and first grandbaby, Megan.

He also liked women’s company more than men’s. For a number of years when I was a kid, we went on vacation to summer cottages in Paw Paw, Michigan. The guys would all go play golf while the women sat on the beach. My dad would stay with the women, sitting under an umbrella in his swim trunks, with Sea & Ski slathered all over his pasty white body, chatting the afternoon away.

THOUGH WE WERE ONLY TWO YEARS APART, JULIE AND I were totally different. From the moment I was born, she was looking to create her own family because she now wanted out of ours. She loved dolls, little kids, and telling people what to do. She was thin and pretty, with long blond hair—the Marcia Brady to my Jan.

But Julie had a great sense of humor—we all did, thanks to our parents, who taught us by example that being the butt of the joke is a badge of honor. Julie was the space cadet, so we Lynches would mock her in a high-pitched dumb-blonde voice that made her giggle. We were not a thin-skinned people.

And although Julie and I fought like crazy, we insisted on sharing not only the same room but the same bed the whole time I was growing up. I still don’t know why. I mean, we hated each other. When I recently asked her what was up with that, she had no answer either. On the same ironic note, we also wrote words to The Newlywed Game theme song about how much we loved being sisters. “Everybody knows who we are / We’re not brothers, you’re a bit too far / We are sisters by far!” I shared the writing credit for this masterpiece with Julie, but in truth, I wrote it all by myself.

My brother, Bob, was the much-awaited son. Dad was ecstatic when he came along two years after me, thinking he’d finally get to partake in the classic American father-son ritual of playing catch. But Bob was shy and not athletic, and he couldn’t have cared less about classic American rituals. I, on the other hand, was a huge tomboy and wanted nothing more than to play baseball from sunup to sundown. I would have killed to play Little League baseball, unlike Bob, who dutifully put on his little uniform every Saturday but just hated it. My dad did enjoy throwing the ball with me, but I always felt like he’d rather have played with Bob.

Unlike me, Bob was quiet, and he did everything he could to avoid getting any attention. Even when he was little, he refused to wear clothes that matched because he didn’t want it to look like he’d tried. He just wanted to blend into the background, which I, the family ham, did not understand at all. Dad would clap him on the back and say, “That’s my boy!” which only caused Bob to shrink in embarrassment. All I could think was I’ll be your boy!

I always felt like I got the middle-child shaft. My parents had their hands full with whatever Julie was demanding at the moment, or they were worried about why Bob was hiding in his room listening to Led Zeppelin. I was the easy one, and I thought that would get me something. I kept offering myself up to occupy the space Bob kept turning down. But I just didn’t have a place. So, of course, the frustration would build and build until I finally pitched a fit: “No one pays attention to ME!” For them it seemed to come from nowhere, and they’d look at me like I had ten heads. I just wanted a little attention.

There was never much discipline in our family, not to mention academic supervision. I’d bring home my report card, and no matter what my grades were, Dad would barely glance at it and then sign it with a flourish and say, “That and a quarter will get you a cup of coffee.” Mom might occasionally throw her hands up and say, “How come nobody brings a book home? Nobody studies around here!” We wouldn’t answer, and she’d forget about it as we all went back to watching Gilligan’s Island. Six months later, she’d say it again: “How come nobody brings a book home?”

On my first-grade report card, my teacher wrote, “Jane does not take pride in her work. She spends too much time talking and visiting.” My mother wrote back, “I spoke to Jane about this and she has promised to do better.” I’m sure that never happened. I could no more stop myself from talking and cutting up than I could stop the earth from turning.

Whether at home or at school, I’d do anything to get laughs or attention. When the phone would ring, I’d rush to it and answer in a baby-talk voice that cracked the family up—“Well hellooooo, who’s calling, please?” Once, when I was about eight, my mom got on the phone after I’d answered it, and I could tell she was defending me. “Well, that was my daughter …. She’s eight …. I beg your pardon!” And she slammed down the phone. I am pretty sure the person on the other end asked if I was developmentally delayed.

My sister was embarrassed by my antics, but my brother, the quiet one, would be smirking in a corner. He was supremely dry in his humor, and because he was so shy, it snuck up on you. He’d come up with a particularly witty youthful retort like “someone’s got their panties in a wad.” I’d watch him walk away so pleased with his little quip that he’d relive the moment by mouthing it silently.

Once, again when I was about eight, my brother was listening to his transistor radio. He kept switching the earpiece from one ear to the other, which I thought was his idea of a joke. “You can’t do that,” I said. “You can only hear out of one ear.”

“No, I can hear out of both,” he answered. And that was how I discovered I was deaf in my right ear. I really thought that everyone could only hear out of one ear, because for as long as I could remember, that had been true for me.

I told my mother that I couldn’t hear out of my right ear, and she took me to the doctor to get checked out. Turns out I have nerve deafness, probably a result of a high fever when I was a baby. My parents had taken me to the hospital, where I was put on ice to bring the fever down, but the right ear must have been already damaged.

I didn’t think too much of it, since I’d been doing fine all this time. But I could hear my mom saying to the doctor in a hushed tone, “Will she live a normal life?” I think this was my mom’s constant concern for me, reflecting her Midwestern priority list, on which “normal life” came right after “food” and “shelter.” But I was thrilled with the diagnosis, because I was finally special—and getting some attention.

It came in handy, too—when I wanted to take revenge on a bully in elementary school. I was a safety patrol officer, which meant I wore an orange vest and helped kids cross the street. When one boy whacked me in the head as he crossed, I pretended he had deafened my one good ear. I made a big deal out of it, holding my head and looking scared, and they called the kid’s mom in. Someone yelled, “CAN YOU HEAR ME?” while I just shook my head and flailed my arms. That kid was in trouble.

AS MUCH AS I JOKED AROUND, AND AS LOVING AS MY parents were, I still always felt a weird, dark energy bottled up inside. Even as a very young kid, I had a sense I was missing out on something. My body was filled with a buzzing nervous tension that constantly threatened to erupt in what my mother came to call “thrashing.”

Whenever the pent-up energy got to be too much, I’d throw myself to the floor and pitch a fit. I’d flail my arms and kick my legs, rolling around like I was possessed. It wasn’t even that I was angry or upset—it was just that I couldn’t take the built-up pressure. I had to release that energy somehow, and the only way that I knew was to have a total spazz-out on the floor.

“Get up! Stop thrashing!” Mom would shriek. She had absolutely no idea what I was doing or why. But I couldn’t get up or stop—not until I’d spewed out whatever was bottled up inside me. It never lasted very long, as I wasn’t really that upset. It was more like this was something my body needed to do—a sudden physical cataclysm, like a violent sneeze.

The problem was, I just never felt quite right—in my body, with my family, in the world. As much fun as I had with my parents, sister, and brother, I still felt like an outsider, like no one understood me at all.

These feelings scared me, so I would joke about them. “I know you adopted me,” I’d announce gravely to my mother. “I know I came from the Greens, down the street.” There were no Greens living on our street, but that was part of the joke. I didn’t belong anywhere, to anyone. I was alone.

I not only felt out of place in my family, I also felt out of place in my own body. Growing up, I didn’t feel like the other girls seemed to feel. I wanted to be a boy. I loved Halloween, because I could dress up as a guy—I was a hobo, a pirate, a ghost who wore a tie, and one year I was excited to dress as Orville Wright for a book report on the Wright Brothers. I went bare chested in the summers until I was eight and my mom finally pulled the plug on that. She grabbed me off my bike and sent me into the house. “Put a shirt on!!” Watching Disney movies, I wanted to be the heroic prince—not the weak, girly, pathetic princess who always needed rescuing. I had no interest in being saved by a guy on a white horse.

Whenever I could get away with it, I’d sneak into my dad’s room and put on his clothes. I loved everything in his closets— his suits, his button-down shirts, his ties, his shoes. I’d dress myself up, fill his martini glass with water, and look at myself in the mirror, sipping my “cocktail” like the quintessential sixties man I longed to be. It was very Mad Men. (This past year I went trick-or-treating as Don Draper. Some things never change.)

I embraced the melodramatic potential of all these feelings clashing around in my body. “No one understands me!” I would cry, hurling myself onto my bed in tears. As I saw it, there was only one person in the world who ever understood me, and he had died on my fourth birthday. My grandfather.

I actually have no idea if Grandpa understood me at all, but this was a useful notion for an emotionally overwrought child to cling to. The family lore was that whenever I came over, he would shout, “Here comes the house wrecker!” He adored me, a truth that seemed obvious enough in one of the few surviving photographs of us together. It was taken in June of 1964, just before my fourth birthday. My sister and I are wearing matching dresses and playing near my grandfather, who is beaming at me with a look of pure love.

Grandpa beams adoringly at me. Oh, and Julie’s there, too.

The fact that he died soon after that picture was taken and on my birthday only added to the mystique, and for years afterward, whenever I felt sad or alone, I’d think to myself, If only Grandpa were alive. He would have appreciated me.

I just wanted to believe that someone, somewhere, understood me. And since Grandpa wasn’t an option, I went for the next best person: Mary Tyler Moore. I watched a lot of television and loved The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Soon, I began imagining myself as a character in it. I’d write scenes for myself, where I’d go to Mary for advice, and she’d look into my eyes and say, “Jane, you are so special.” In my scenes, Mary and I had a very sweet, tender relationship. She got me.

When I was twelve, the feeling that I was odd and misunderstood jumped to a whole new level. That was the year my friends the Stevenson twins gave a name to another feeling I’d been having.

Jill and Michelle Stevenson were in my class at school, and every year during spring break they went with their parents to South Florida. They told me about a weird thing they’d seen there. “Sometimes,” Jill said, “you’ll see boys holding hands with each other on the beach, instead of with girls. It’s because they’re gay.”

They could already procure a tone of scandal and disgust, as if the subject were the sexual proclivities of circus freaks. I just stood there in shock.

Oh my god, I thought, that’s what I have. I’m the girl version of that.

No sooner had this thought burst into my head than another followed: No one can ever, ever know. I may have only just learned what being “gay” meant, but I knew instinctively it was a disease and a curse. I’d always had crushes on girls and hadn’t really thought too much about it. But watching the Stevenson twins’ mortification about the South Florida boys told me everything I needed to know: being “gay” was sick and perverse, and if you had the misfortune of being that way, you’d better hope no one ever found out.