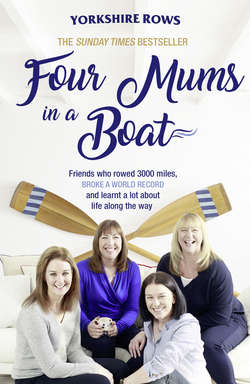

Читать книгу Four Mums in a Boat: Friends who rowed 3000 miles, broke a world record and learnt a lot about life along the way - Janette Benaddi, Janette Benaddi - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

Holding On

‘The sky is not my limit … I am.’

T. F. HODGE

20 December 2015, San Sebastián Marina, La Gomera

The day itself started early: there was a briefing at 7 a.m. Not that the early start mattered that much, as none of us had really slept the night before. It was more than nerves. It was a terrifying feeling, not being able to stop something we had put in motion all that time ago. We had been waiting for this day for so long and now it was here. Very early, we enjoyed a ‘last breakfast’ at a café on the seafront, quietly savouring the last proper meal we would eat for possibly the next three months and deep in our own thoughts. We were lingering – it was as if no one quite wanted to leave.

Janette piped up into the silence.

‘I feel so nervous, as if I’m about to get married again!’

‘What the hell are we doing?’ asked Helen.

‘Who knows?’ replied Niki. And we all looked at one another.

‘Well, come on then!’ said Frances, standing up. As the one who’d got us into all of this, she wasn’t going to allow us to sit around as if there was nowhere else we should be. ‘Let’s do this!’ And with that, she led us out, leaving the table and, indeed, her sunglasses behind.

The briefing room was silent, but we were worried and disconcerted to see that Lauren from Row Like a Girl was visibly upset as we listened to Carsten Heron Olsen, CEO and race director, run through his last-minute safety list. Quite apart from how sorry we felt for her, she was one of the few who knew what it was really like out there. And the gift given to each of the boats in the race from the people of La Gomera did not help much either. It was a gladdening picture of the Holy Mary to stick on the wall of the cabin, which (we noticed) no one refused. It was like we were being read our last rites. What the hell had we let ourselves in for?

The silent, tense atmosphere of the briefing was in massive contrast to the noise outside. We walked, blinking, into the sunlight to be faced with cheering, waving crowds and a loud local band. The sound was overwhelming and as the deafening drums beat out some unrecognisable tune, we all processed in silence behind.

Yorkshire Rows had been given the honour of going first out of the harbour. The fours were leading out and we’d been chosen to head the race out of San Sebastián into the Atlantic. It would probably be the only time we would be leading the race itself and we felt extremely proud and sick with nerves as we walked towards Rose, moored up on the pontoon. Our hearts were pounding. Our hands were sweating. This was it. There was no turning back. Helen, who is normally one of the most garrulous of us all, was completely silent. We were trying to focus. Then, what had begun in apparent slow motion began to frantically speed up. Suddenly it felt like a panic, as we all started asking if we had everything. Where was this? That? Frances had lost her sunglasses. Where the hell were they? Janette was fumbling with the tiller, making those last-minute skipper checks – battery levels, harnesses and comms. Niki’s feet wouldn’t fit in her shoes and Helen was looking for some sort of sign that everything was going to be fine.

Looking for signs is Helen’s thing. She has a very close friend, Dawn, who reads angel cards and tarot.

‘It was through her that I learnt about looking for signs,’ she once explained to the rest of us. ‘You just have to open your eyes to see them, whereas before I would have my head down and didn’t look at what was around me and didn’t see the opportunities or the potential in any situation. But she taught me that actually you’ve got to look, and there’s always someone ready to help you, supporting you. But you have to look and listen.’

In the run-up to the race Helen was seeing signs all the time. She’d go into restaurants and there would be oars on the wall. She went on holiday to a cottage in Robin Hood’s Bay only to find a great big blade in the kitchen. But feathers are really her thing. She sees them everywhere. They are small indications of affirmation and support.

‘Helen!’ shouted Sarah, one of the PR girls working for Talisker, as we were poised at the oars, about to set off. ‘Look! Look in the water beside you!’ We all turned and there, sure enough, floating in the water right next to Helen, was a large white feather.

‘There you go!’ she smiled as she nodded down at the sea. ‘It will all be fine. We will make it across! Just you wait and see…

And so we set off towards the start line. With Janette at the helm, we rowed with all three of us up on the oars, with as much style and panache as we could manage. We were very conscious that our families would be watching the start on BBC Breakfast, curled up on the sofa at home, five days before Christmas and without their mums. We wanted to give them a bit of a show.

‘Okay, ladies,’ grinned Janette as we lined up at the start, surrounded by small boats, larger vessels, TV crews, a circling helicopter, shouting, waving crowds and Wayne and Tracy. ‘Let’s show them how it’s done!’

We were poised to go. Janette held onto the mooring line with Carsten gripping the other end. This was the only thing that was stopping us from leaving. Carsten kissed Janette on the cheek.

‘Good luck,’ he said. ‘I’ll see you in Antigua.’ He let go of the rope. Our last contact with land.

Janette pulled it on board. It felt strange. This was it. We were leaving. Our hearts were pounding. It was nerve-racking. It was our last touch. Our last bit of contact with land, with anyone else.

From now on it would be just us four. It was going to be tough, but we were going to make damn sure we managed it.

Janette stood tall. She was ready to steer the way. She knew we’d give it everything we could to show to the world we were ready, we were strong and we were women.

‘Come on, girls,’ she urged, her blonde hair whipping around her face. ‘Let’s do this!’

Carsten sounded the klaxon and the loud, shrieking blast echoed around the harbour. The crowds roared and we were off, rowing in unison, giving it our best in our black Lycra rowing shorts and our Talisker vests, pulling our oars through the water powerfully and in time, together.

‘One! Two!’ shouted Janette from the helm. ‘Smile!’ she urged. ‘I feel like Queen Boadicea in the middle of her slaves!’ She laughed. ‘We’re Amazons!’

‘Quite elderly Amazons,’ said Frances, as she slid back and forth on her seat.

‘Middle-aged,’ corrected Niki.

‘Middle-aged Amazons!’ agreed Helen. ‘Who ARE going to cross an ocean!’

The boats left La Gomera at 15-minute intervals, and it wasn’t long before we watched Row Like a Girl power past us. We had held the lead in the race for precisely half an hour! Possibly less. Not that we minded; we were more interested in hitting the first waypoint (a marker), which we had dutifully programmed into our GPS system and were trying to head towards, despite the ever-increasing swell. The problem, we soon realised, with being first out of the harbour is that you have no one to follow! And it didn’t take long before all the other rowers had also left La Gomera and disappeared.

One moment we could see an ocean littered with boats – friends that we had made over the three weeks that we had spent on the island. And then, all of a sudden, we were alone. It was like an oceanic game of hide and seek. We were on our own.

There was no time to worry about this, for even with land still firmly in sight, the ocean had plans. The waves were growing and the current grew stronger, and Rose was being pulled along in it. Time and again we tried to row, and time and again the oars were being wrenched out of our hands. It was painful. The sea was so strong that we could not get any purchase in the waves, and when we did the oars would shoot out of the water, sending us and them flying backwards, hitting us in the legs and the thighs, garrotting us or, even worse, whacking us extremely hard in the pubic bone. It was agony, and not what we had trained for at all. It was also cold, freezing cold, as wave after 40-foot wave broke over us, dousing us in icy salt water. We were being lashed from left and right, the oars flying everywhere. It was truly a baptism of fire; we were taking our wet-weather gear on and off constantly, and clinging onto the boat for dear life. And we had only just gone out to sea.

‘Call this a rowing race?’ shouted Frances as she held onto the side of the boat, as we rode yet another wall of 40-foot waves. ‘This is just holding on!’

‘I hate these waves,’ said Helen. ‘I can’t believe they are SO big.’

‘These aren’t big!’ shouted Janette. ‘This is nothing – 40 foot is nothing – 40 foot is easy.’ She smiled. ‘We’re perfectly safe.’

‘It’s like the best rollercoaster ride!’ grinned Niki, who, out of all four of us, was the one loving it the most. We were hitting 3.5 knots without even putting an oar in the water. Who knew she was such a speed freak?

Meanwhile, everything was an effort. Moving around on the boat was so difficult. Constrained by our bulky wet-weather gear and the extreme rocking with the waves, even the smallest thing seemed impossible. Cooking was actually dangerous. The simple task of boiling some water and then trying to rehydrate a bag of chicken curry or beef stew could take up to 45 minutes at a time, as splashes of scalding hot water sloshed all over the place.

But going to the toilet was the worst. We had two buckets – one for washing in and the other for doing our business. Being resourceful ladies we had naturally customised our toilet bucket with a grey plastic lav seat for a more comfortable experience. However, it is difficult to do one’s business with your weatherproof salopettes around your ankles while riding a rollercoaster wave, with a biodegradable wet wipe in your hand. Not forgetting the audience. In the front row.

Not that any of us really cared about that. We’d seen each other in all forms of undress in the build-up to the race. We had shared more dodgy hotel rooms with badly plumbed bathrooms than we cared to remember. So performing on a bucket in front of the group was not the problem; staying on the bucket was. And keeping the contents of the bucket from flying back into the boat after you hurled it overboard or avoiding spilling it all over your fellow rower was something of a challenge. Also, remembering to fill it with a little water before sitting on it was clearly trickier for some members of the crew than for others. Helen was always the one having to scrub out her bucket after being surprised by her sudden need to go to the loo.

Despite the huge waves and the strong current, we were sticking to our plan of rowing two hours on, two hours off. We were on the oars in our pairings of Frances and Niki, and Janette and Helen, keeping to our schedule and pointing the bow towards Antigua, 3,000 miles away.

Even Helen. Every two hours she would come out of the diminutive cabin she was sharing with Niki and she would throw up, get on the oars, throw up, either row or not row, throw up. And she would remain there for the next two hours, being battered by the waves and throwing up, before it was her turn to go back into the cabin. Then she would get off her seat, throw up, knock on the cabin door to get Niki out of bed, throw up again, before dragging herself into the cabin, where she would lie, without moving, until she was called back up on deck again two hours later.

The only two things that kept Helen going during those first few days were mugs of Ultra Fuel (an all-singing, all-dancing liquid meal-replacement drink, developed from extreme sports) and Niki. Every time Helen came off shift, Niki made her a mixture of Ultra Fuel and water, which Helen would sip in tiny mouthfuls, while lying motionless, for the next two hours. Oddly, Helen was not sick when she was lying down, and those precious minutes allowed her to metabolise the nutrients in the drink and prevent total dehydration. And dehydration on the ocean can be fatal, or at least fatal to your ambitions of finishing the race, as once it kicks in it is extremely difficult to combat. Which is exactly what happened to poor Nick Khan in the Latitude 35 team – after 10 days of chronic seasickness, he had to be medivacked off the boat when he was found deliriously shouting at the sea and saying he wanted to die. He had no choice but to leave the boat (along with another crew member who’d decided it was no longer safe for him to continue), leaving the remaining pair to row the four-man boat without them.

So we all kept an eye on Helen. Well, Niki did. Sympathy, or indeed empathy, is not something that courses freely through the veins of either Janette or Frances. They are more Yorkshire than pudding, and their suffering of fools and vomitus is limited to say the least. But what neither of them could fault Helen on was her absolute determination to keep on going during those first 72 hours. She was not so much ‘eat, sleep, row, repeat’; more ‘puke, sleep, puke, row, puke, repeat’. It was impressive. Her eyes were glazed, her conversation was non-existent, but still she managed to row. The waves crashed against the side of the boat and Helen stood firm. ‘Just a few more days,’ we all kept on thinking; just a few more days and we hoped Helen would be able to crack a smile and keep down the all-in-one breakfast-in-a-bag.

But it was about 2 a.m. in the morning on the third day when disaster struck. The boat was lurching from side to side in the huge waves, the few lights we had on board were flickering and it was Helen’s turn up on the oars.

‘Five minutes!’ yelled Niki, knocking on the door to the sealed cabin.

‘What do you think?’ asked Janette through the darkness, sliding back and forth on her seat. ‘Do you think Helen is any better?’

‘A bit,’ said Niki, holding onto the boat while trying to slip out of her wet-weather gear. ‘She is being very brave. Stick to the Ultra Fuel and I’m sure she’ll pull through, eventually.’

Just then a huge wave hit the side of the boat, sending Niki flying. With one leg still in her trousers, she didn’t stand a chance as she was hurled against a metal peg that sank hard into the base of her spine.

‘Oh my GOD!’ she screamed in the darkness. ‘Oh my GO-O-OD!’

‘Are you okay?’ Janette leapt off the oars.

Niki was writhing around in the water at the bottom of the boat, screaming and clutching the base of her spine. Both Frances and Helen appeared, from either end of the boat.

‘No! NO! I am not!’

‘Are you hurt?’

‘Yes! My bum, my bum –’

Niki was shaking and stammering with cold and pain.

‘Have you broken anything? Cut anything? Is there blood?’ asked Janette, scrabbling about in the darkness.

‘No. I don’t know… my back, my coccyx, my pelvis. It’s agony… Aaaah – this is worse than childbirth! Worse… than… bloody… child-birth!’

‘Here,’ shouted Frances, staggering towards her. ‘Here’s the medical bag.’

‘Okay, okay,’ said Janette, leaning over and grabbing the bag. ‘On a scale of one to ten. One to ten, remember. What is your pain?’

‘Oh, Jesus Christ!’ spat Niki. ‘Once a nurse, always a bloody nurse.’ Janette was indeed once a nurse.

‘It’s a ten! Of course it’s a ten!’

‘Okay, okay,’ said Janette, fumbling through the bag in the darkness. ‘How about… paracetamol? No.Tramadol? Or…’ She strained to read the label in the dark. ‘Diclofenac?’

‘What’s that?’

‘It’s a painkiller and an anti-inflammatory.’

‘What will it do?’ gasped Niki.

‘Make you go… um, diclofuckit?’ suggested Janette.

‘I’ll have two diclofuckits,’ said Niki desperately.

‘Two,’ nodded Janette in agreement.

‘And I don’t know what you’re looking at,’ said Niki, lying flat at the bottom of the boat, staring up at Frances as yet another wave crashed overhead. ‘It’s all your fault we’re here!’

‘Yeah!’ agreed Helen, speaking for the first time in 24 hours. ‘This is the last time I listen to any of your bright ideas.’

SHIP’S LOG:

‘We were holding on, yet at the same time we were letting go. The first 24 hours of our row were about letting go – letting go of life enough so that we could venture into the unknown. Each of us had to eventually stop looking at the outline of the land and turn instead towards the vast open ocean. That first stroke of the oars away from the shore was our first step into an unknown world. It takes courage to let go of what you are familiar with. Once the step has been taken, there is no knowing how the ride will go – and that’s the fun part.’

(JANETTE/SKIPPER)