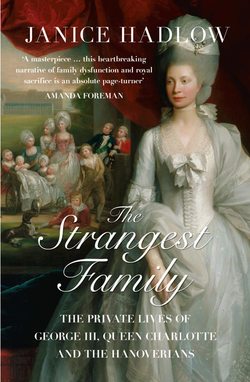

Читать книгу The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians - Janice Hadlow - Страница 13

CHAPTER 3 Son and Heir

ОглавлениеFREDERICK AND AUGUSTA’S FIRST SON, George, was born on 24 May 1738 at Norfolk House in St James’s Square. He was a seven months’ child, and ‘so weakly at the time of his birth, that serious apprehensions were entertained that it would be impossible to rear him’.1 He was baptised that night, noted the diarist Lord Egmont, ‘there being a doubt that he could live’, but like his sister before him, the baby George clung tenaciously to life.2 In later years, he had no doubt whom he had to thank for his survival: Mary Smith, his wet nurse, ‘the fine, healthy, fresh-coloured wife of a gardener’. When she died in 1773, George was still conscious of the debt of gratitude he bore her. ‘She suckled me,’ he recalled, ‘and to her great attention my having been reared is greatly owing.’3 When told that etiquette made it impossible for the infant George to sleep with her, she had ‘instantly revolted, and in terms both warm and blunt, she thus expressed herself: “Not sleep with me! Then you may nurse the boy yourselves!”’4 The forthright Mary Smith won the battle, and with it the unwavering affection of the prince.

In 1743, Frederick moved his growing family – another son Edward had been born in 1739, and six other children were to follow, in almost annual succession over the next decade – to a bigger establishment. Leicester House, a large but ugly building, stood on the north side of what is now Leicester Square. It was not the most fashionable of neighbourhoods, being rather too near louche Soho for the politest society, and Frederick was by far its grandest inhabitant. His neighbours were businessmen, musicians and artists, most notably William Hogarth who had his studios across the square at number 32. Frederick was not short of places to live – he spent a great deal of money on nearby Carlton House, and rented properties for the summer on the Thames at Kew and at Cliveden – but it was Leicester House that became his principal residence. It was where he held informal court, assembling around him a group of ambitious young men who were as impatient as he was with his father’s government. With their support, Leicester House became the basis for Frederick’s political operations, the campaign headquarters from which he directed his attacks on the king’s ministers with such sustained effort that the term ‘Leicester House’ soon became synonymous with the very idea of princely political opposition. But the Soho property was also a family home; all Frederick and Augusta’s children grew up there, and their eldest son George seems to have retained an affection for it; he used it as his London house until very shortly before he became king.

George II never visited. He remained estranged from his son, although with the death of Queen Caroline some of the furious antipathy that had characterised their relationship ebbed away. The king occupied himself with his cards, his mistress and his military campaigns. His only engagement with Frederick was through the distancing formalities of party politics, where the two fought out their differences by ministerial and opposition proxies. They took care never to meet. Horace Walpole was once at a fashionable party where the usual precautions had somehow failed, and Frederick and his father were both embarrassingly present (‘There was so little company that I was afraid they would be forced to walk about together’), but this was a rare occurrence.5 Beyond the public stage of politics, the prince and the king lived carefully segregated existences.

Although he was now both paterfamilias and politician, Frederick continued to conduct his life with the same breezy goodwill and indifference to criticism that had so infuriated his parents when he was younger. If his ability to tell people what they wanted to hear coined him a reputation for duplicity, and his relaxed attitude to matters of political principle led to accusations of inconstancy, he was also singularly lacking in the anger and suppressed rage that had characterised so much of his parents’ lives. If he was resentful at their treatment of him, he concealed it very well; in public he appeared to be entirely unmarked by their baroque hostility. He was the least bitter of the early Hanoverians and, as such, seemed to have the best opportunity to the break the inheritance of dynastic unhappiness which his parents had passed on to him with such relish. In many ways, and with profound consequences for the development of his eldest son’s character, Frederick rose to the challenge. In his attitude to his wife and family, he represents a crucial and often underestimated bridge between the very different worlds of George II and George III.

Frederick’s conception of family life did not, however, extend to the practice of conjugal fidelity. He was his father’s son in that, at least. One of his favourites was Grace, Lady Middlesex, whom Horace Walpole described as ‘very short, very plain, and very yellow’. But, as Walpole saw, none of these affairs really mattered; they certainly did not disrupt the settled ecology of Frederick’s marriage, as those of his father had done: ‘Though these mistresses were pretty much declared, he was a good husband.’ Augusta, sensibly in Walpole’s opinion, ignored the transient lovers and reaped the benefits as a result. ‘The quiet inoffensive good sense of the princess (who had never said a foolish thing, nor done a disobliging one since the day of her arrival) … was always likely to have preserved her ascendancy over him.’6 Frederick’s relationship with his wife had none of the obsessive, jealous intensity that marked his father’s feelings for his mother; nor did it have about it the toxic undercurrents that damaged so many of those who came into too close contact with his parents’ passion.

His marriage was entirely lacking in the drama that characterised George and Caroline’s union, yet there is little doubt that Frederick loved and desired his wife. The prince, who was proud of his literary talents, wrote a series of verses to Augusta celebrating her physical charms, including ‘those breasts that swell to meet my love,/That easy sloping waist, that form divine’. But as the poem made clear, it was not her body for which her husband most admired her: ‘No – ’tis the gentleness of mind, that love,/so kindly answering my desire/ … That thus has set my soul on fire.’7 It was Augusta’s mild, unchallenging personality that Frederick found particularly appealing. From the earliest days of their marriage he had been delighted to discover that his wife was everything his mother was not: calm and pliable, with no discernible tastes or ambitions other than those her husband encouraged her to share. Her docility was one of her chief attractions, as Augusta herself seems clearly to have understood. Throughout their marriage, she never did or said anything to discommode or contradict him. One of the prince’s friends, in a parody of Frederick’s uxorious verses, added to the list of Augusta’s virtues ‘that all-consenting tongue,/that never puts me in the wrong’.8

Augusta’s willingness to please extended not just to what she said but also to what she did. She patiently indulged her husband in all his interests and foibles; in return, he found a place for her at the centre of his life. She accompanied him on all his excursions. Sometimes twice a week, they went to formal masquerades at Ranelagh pleasure gardens, where the princess, usually very modestly dressed, appeared ‘covered with diamonds’. Augusta gamely joined her husband in his pursuit of less grand entertainments. They went together to investigate the infamous Cock Lane Ghost, whose alleged spectral manifestation drew large crowds nightly (though the spirit failed to appear for them). She was also a dutiful participant in the pranks that Frederick enjoyed so much, reacting with the expected surprise when taken by him to visit a fortune teller, who turned out to be their children’s dancing master in heavy disguise. The politician George Dodington, who occupied a prominent place in the prince’s entourage, joined them on a typical day out in June 1750: ‘To Spitalfields, to see the manufactures of silk, and to Mr Carr’s shop in the morning. In the afternoon, the same company … to Norwood Forest to see a settlement of gypsies. We returned and went to Bettesworth the conjuror’s in hackney coaches – not finding him, we went in search of the little Dutchman, but were disappointed; and concluded by supping with Mrs Cannon, the princess’s midwife.’9

If the princess found Frederick’s pursuit of the eccentric and the exotic exhausting, she would never have said so. Perhaps she took more pleasure in their shared botanical interests. She and Frederick laid out the foundations of what is now Kew Gardens, jointly commissioning a summerhouse in the fashionable Chinese style, decorated with illustrations of the life of Confucius. Like her mother-in-law, Augusta’s only real extravagance was her spending on the gardens, where she built on the work Caroline had begun, erecting an orangery and completing the famous pagoda.

She played a less significant part in her husband’s other interests. For all his enduring fascination with low-life, Frederick was also a sophisticated consumer of high culture and keen to be seen as an urbane and discerning man of taste. He was a patron of the architect William Kent, and employed him to remodel the interior of his houses in his severe, classical style. In contrast to his father’s boasted indifference to the quality of the paintings that hung on his walls, Frederick was a thoughtful collector of pictures, buying two Van Dycks and two landscapes by Rubens. Horace Walpole, who was not well disposed to the prince, regarded his artistic ambitions as mere pretension until Frederick asked to see the catalogue Walpole had drawn up of his father’s extensive art collection at Houghton Hall in Norfolk. To his surprise, Walpole was impressed by the prince’s knowledge and appreciation: ‘He turned to me and said such a crowd of civil things that I did not know what to answer; he commended the style of quotations; said I had sent him back to his Livy.’10

Frederick was his mother’s son in his respect for intellectuals, if in little else. Like her, he enjoyed the company of writers. A keen amateur author himself (besides the poem written for Augusta and the disastrous play co-written with Hervey, he had a host of other works to his name), he sought out the company of John Gay, whose Beggar’s Opera, with its attack on Robert Walpole and the king, was attractive to him both culturally and politically, and James Thomson, whose poem The Seasons was hugely popular in the 1730s, and often visited Alexander Pope at his home in Twickenham. When Pope fell asleep in the middle of one of Frederick’s disquisitions on literature, the prince was not offended but stole discreetly away.

Built on the foundation of their stable marriage, and enlivened by the energy and diversity of the prince’s interests, Frederick and Augusta’s household was a comparatively happy place in which to raise children. It was certainly an improvement on Frederick’s, or indeed on his father’s, experiences of childhood. There seems little doubt that this was a conscious effort on Frederick’s part; he was determined to create for his own family the life he had never enjoyed himself as a boy. He was an attentive and affectionate parent, who enjoyed the company of his wife and children and was not afraid to show it. ‘He played the part of the father and husband well,’ wrote one appreciative visitor, ‘always happy in the bosom of his family, left them with regret and met them again with smiles, kisses and tears.’11 When the Bishop of Salisbury went to dinner with Frederick and Augusta, he was impressed to see that afterwards the children were called in, ‘and were made to repeat several beautiful passages out of plays and poems’ whilst their proud parents looked on. Beguiled by this unaccustomed image of royal family harmony, the bishop declared ‘he had never passed a more agreeable day in his whole life’.12 Frederick was particularly attached to his two eldest boys. When he was away, he was a diligent correspondent, his letters suffused with a warm informality. Writing to ‘dear George’ in 1748, he signed himself ‘your friend and father’. To ‘dear Edward’ he ‘rejoiced to find that you have been so good both. Pray God it may continue. Nothing gives a father who loves his children so well as I do so much satisfaction as to hear they improve, or are likely to make a figure in this world.’13 ‘Pray God,’ he once wrote, more wistfully, ‘that you may grow in every respect above me – good night, my dear children’.14

Frederick involved himself in every aspect of his children’s lives. In the country, whether at Kew or Cliveden, he arranged sports for them. There were skittles and rounders – played inside the house if wet, amidst the formal elegance of William Kent’s interiors. Everyone, including the girls, played cricket. All visitors were expected to join in, with neither age, dignity nor excess weight conferring exemption. When the rotund politician Dodington visited Kew in October 1750, he found himself reluctantly conscripted into a game. Further exercise for the royal children was provided by gardening. Each of them had a small plot to tend, but tilling the soil was not confined to the young. Here too, as the unhappy Dodington discovered, guests were compelled to do their bit, hoeing and digging with the rest of the family. ‘All of us, men, women and children worked at the same place,’ Dodington noted on 28 February 1750, adding the mournful postscript, ‘Cold dinner.’15 Having endured the perils of the cricket pitch and the rigours of the garden plot, visitors were also expected to join willingly in the practical jokes and horseplay for which Frederick never lost his taste. Dodington, who was almost as fat as he was tall, once allowed Frederick to wrap him in a blanket and roll him downstairs. The prince’s inner circle was not a place where ambitious politicians could expect to stand on their dignity.

In the evenings, the prince staged elaborate nightly theatricals in which all the family took part. Dodington recorded each night’s offering in his diary; the range of works was extensive, encompassing the classics – Macbeth, Tartuffe, Henry IV – to forgotten lighter pieces such as The Lottery or The Morning Bride. James Quin, a London actor, was recruited to coach the royal children in their performances. Many years later, when George III made his first speech from the throne as king, Quin commented with pride that ‘’Twas I that taught the boy to speak.’16 One of Frederick’s favourite pieces was Addison’s Cato, whose Prologue, with its enthusiastic endorsement of the principles of political liberty, was usually given to the young George to recite, as he did for the first time in 1749 at the age of eleven.

Should this superior to my years be thought,

Know – ’tis the first great lesson I was taught,

What, tho’ a boy! It may in truth be said,

A boy in England bred,

Where freedom becomes the earliest state,

For there the love of liberty’s innate.

If Frederick’s tastes shaped the leisure hours of his children, he was just as active in managing their education. He himself drew up a scholastic timetable, ‘The Hours of the Two Eldest Princes’, which laid out when and what George and Edward were to be taught, and appointed the Reverend Francis Ayscough as their tutor. Ayscough, a doctor of divinity, was not very inspiring, but the boys made steady progress under his instruction, and by the time he was eight, George could speak and write English and German. Frederick had the two boys painted with their tutor, who looms above them, formal in black clerical dress. Grey classical pillars rise behind them. The overwhelming impression is of chilly dourness; this was not, it seems, an atmosphere in which learning was likely to deliver either pleasure or excitement.

Then, in 1749 – the same year that the carefully coached eleven-year-old George delivered his eulogy on English liberty – Frederick replaced Ayscough with a far abler man. George Lewis Scott was a barrister and an extremely accomplished mathematician, and his arrival signified the prince’s intention to accelerate his sons’ academic progress. Their working day was long – they were required to translate a passage from Caesar’s Commentaries before breakfast – and the curriculum broad, including geometry, arithmetic, dancing and French. Greek was introduced for the first time, and after dinner, the boys were to read ‘useful and entertaining books, such as Addison’s works, and particularly his political papers’.17

The more demanding timetable reflected a new sense of urgency that had entered Frederick’s thinking, particularly in relation to his eldest son. At the beginning of 1749, he had composed a paper intended for the guidance of his heir. Its intentions were clearly set out in the title the prince gave it: ‘Instructions for my son George, drawn by myself, for his good, and that of my family, for that of his people, according to the ideas of my grandfather and best friend, George I.’ It was addressed directly and personally to his son. If Frederick were to die before he could himself elaborate on its contents to the boy, it was to be held by Augusta, ‘who will read it to you from time to time, and will give it to you when you come of age to get the crown’. ‘My design,’ Frederick promised, ‘is not to leave you a sermon as is undoubtedly done by persons of my rank. ’Tis not out of vanity I write this; it is out of love to you, and to the public. It is for your good and for that of the people you are to govern, that I leave this to you.’18 What followed was a detailed blueprint for good government, as seen through Frederick’s eyes. It sought to impress on George the nature of his future duties as king, head of his family, and father of the people. It stressed the importance of identifying himself with the country he would one day rule (‘Convince the Nation that you are not only an Englishman born and bred, but that you are also this by inclination’).19 It urged him to decrease the national debt, and to separate the electorate of Hanover from Great Britain to minimise involvement in European wars.20 Such policies would reduce expenditure, making the king more solvent, less dependent on forging alliances with political parties, and free to pursue policies of his own devising. These, Frederick asserted, would be more likely to reflect the true national interest than the existing system, reliant as it was on the management of a host of often conflicting and selfish sectional interests. When presented to his son later as part of a wider constitutional framework, these were ideas that would prove very compelling to the young George; but what prompted his father to articulate them at that time, in a form that suggested so powerfully a kind of political last will and testament?

Although Frederick was only forty-two when he wrote the document, the 1740s had been a punishing decade for him and his followers. They had enjoyed some successes, most notably, and most pleasing from the perspective of Leicester House, the fall of George II’s favoured minister Robert Walpole in 1742. The prince did not entirely engineer Walpole’s defeat, but when begged by the king to save him, he refused to help the stricken politician. It had proved hard to capitalise on such triumphs. George II had denied Frederick a role in the army, both in the Continental wars of the mid-1740s and during the Jacobite rising of 1745. On both occasions he was forced to watch, humiliated, from the sidelines as his father and his younger brother William, Duke of Cumberland, rode to victory respectively at Dettingen and Culloden. Then, in 1747, Frederick’s followers were roundly defeated at the general election.

By the end of the decade, he was forced to come to terms with the ambivalence of his position. As Prince of Wales he was master of an alternative court, with over two hundred household posts at his disposal and the promise of preferment once he, eventually, came to power; but although he might be able to undermine or even destroy administrations, he could never be part of them himself. He could break, but he could not build; or at least, not until the king died. Dodington, now acting as one of the prince’s advisers, counselled waiting; but as he approached middle age, Fredrick’s appetite for the struggle seems, surely and steadily, to have ebbed away. Perhaps he suspected that the chances of achieving his ambitions were always going to be limited by the circumstances of his birth. He knew that, unlike his son, he could never be ‘an Englishman born and bred’, and gradually, he began to transfer his hopes for the fulfilment of his long-term goals beyond the possibilities offered by his own reign, concentrating instead on that of his heir. Writing his letter of ‘Instructions’ marked the beginning of that process. It was a sign of both what he hoped his son might one day achieve, and what he had gradually abandoned for himself. And if it marked the level of his ambitions for George, it was also perhaps a measure of his concern. He spelt out his blueprint for the future with such clarity perhaps because he had begun to doubt whether, without such precise guidance, the boy would ever be capable of achieving it. For, as he grew older, George did not seem to anyone – and possibly not even to his father – quite the stuff of which successful kings were made.

*

Though never a voluble child, with age George became steadily shyer, more awkward and withdrawn. He was ‘silent, modest and easily abashed’, said Louisa Stuart, whose father, the Earl of Bute, was one of Frederick’s intimate circle. She maintained that George’s parents, frustrated by his reticence, much preferred his brother Edward. ‘He was decidedly their favourite, and their preference of him to his elder brother openly avowed.’21 Edward was everything his older brother was not: confident, cheerful, talkative and spirited. Horace Walpole, who knew Edward well in later life, described him tellingly as ‘a sayer of things’. His natural confidence, thought Louisa Stuart, ‘was hourly strengthened by encouragement, which enabled him to join in or interrupt conversation and always say something which the obsequious hearers were ready to applaud’. It was very different for his diffident elder brother. ‘If he ever faltered out an opinion, it was passed by unnoticed; sometimes it was knocked down at once with – “Do hold your tongue, George, don’t talk like a fool.”’22

Frederick, it seemed, for all his genuine affection for his children, was still Hanoverian enough to prefer the spare to the heir. He was never deliberately harsh to his mute and anxious eldest son; but he was often exasperated by his unresponsiveness, and failed to understand its causes. He insisted to the boy that his ‘great fault’ was ‘that nonchalance you have of not caring enough to please’.23 He did not see that there was not a scrap of insouciance in George’s make-up, and that his son’s diffidence arose not from nonchalance but from a paralysing lack of confidence in his ability to fulfil his destiny. For Louisa Stuart, Frederick was less to blame than his wife. Beneath the compliant surface she presented to the world, Augusta nurtured a severe and unflinching personality, with a strong tendency to judge others harshly. It was Augusta, she said, who was ‘too impressed by vivacity and confidence’ and who failed to see that ‘diffidence was often the product of a truly thoughtful understanding’. She did not recognise the true strengths of her stolid elder son, ‘whose real good sense, innate rectitude, unspeakably kind heart, and genuine manliness of spirit were overlooked in his youth, and indeed, not appreciated till a much later time’.24

Had Frederick lived, the warmth of the genuine affection he felt for all his children might eventually have buoyed up the spirits of his tremulous heir; George might have matured under the protection of a father who, for all his criticism of his son’s shortcomings and lack of insight into their causes, nevertheless saw the protection of the boy’s long-term interests as his most important responsibility. But at the beginning of March 1751, the prince caught a cold. A week later, on the 13th, Dodington noted in his diary that ‘the prince did not appear, having a return of pain in his side’.25 He was probably suffering from pneumonia. For a few days, he seemed to improve. Augusta, who was five months pregnant, informed Egmont that Frederick ‘was getting much better, and only wanted time to recover his strength’. She added that ‘he was always frightened for himself when he was the least out of order, but that she had laughed him out of it, and would never humour him in these fancies’. She hoped her attempts to raise his spirits had worked as Frederick now declared that ‘he should not die in this bout, but for the future, would take more care of himself’.26

Dodington called at Leicester House on the 20th, and he too was reassured on hearing that Frederick ‘was much better and had slept eight hours the night before’. Everyone’s optimism was unfounded. Later that night, at a quarter to ten, Frederick died. The end came with shocking swiftness. Dodington reported that ‘until half an hour before he was very cheerful, asked to see some of his friends, ate some bread and butter and drank coffee’.27 Walpole heard a similar story. The prince seemed to be over the worst and beginning to improve when he was suddenly overcome with a fit of coughing. At first, Dr Wilmot, who attended him, thought this was a good sign, telling him hopefully: ‘Sir, you have brought up all the phlegm; I hope this will be over in a quarter of an hour, and that your highness will have a good night.’ But Hawkins, the second doctor, was less optimistic, declaring ominously: ‘Here is something I don’t like.’ The cough became increasingly violent. Frederick, panicking, declared that he was dying. His German valet, who held him in his arms, ‘felt him shiver and cried, “Good God! The prince is going.” The princess, who was at the foot of the bed, snatched up a candle, but before she got to him, he was dead.’28 He was forty-four years old.

The king received the news of Frederick’s death as he sat playing cards. George had not remarried; he had kept his promise to his dying queen, taking a mistress rather than a wife. He had sent for Mme de Wallmoden, who divorced her husband and in 1740 was given the title of the Countess of Yarmouth. It was to her that the king turned first. ‘He went down to Lady Yarmouth looking extremely pale and shocked, and only said, “Il est mort!”’29 Once the horror of the moment had passed, the king, who was too self-absorbed to be a hypocrite, did not pretend to be grieved. He had hated his son for years, and his sudden and unexpected death provoked no remorse for his behaviour. As 1751 drew to a close, he commented with characteristic candour: ‘This has been a fatal year to my family. I have lost my eldest son, but I was glad of it.’30 It was his final comment on a relationship which had begun in suspicion, matured into vicious acrimony and ended with estrangement. He felt neither guilt nor regret for what had happened, and never referred to Frederick again.

The prince’s funeral was the final reflection of his father’s disdain. It was, thought Dodington, a shameful affair, ‘which sunk me so low that for the first hour, I was incapable of making any observation’. No food was provided for those of his household who stood loyally by Frederick’s body as he lay in state; they ‘were forced to bespeak a great cold dinner from a common tavern in the neighbourhood’. No arrangements had been made to shelter mourners from the rain as they walked from the House of Lords to Westminster Abbey. The funeral service itself ‘was performed without anthem or organ’ and neither the king nor Frederick’s brother the Duke of Cumberland attended.31 Even in the performance of his last duty to his son, George II could find no generosity of spirit.

He appeared in a better light on his first visit to Frederick’s bereaved wife and children, when he was clearly moved by their stricken condition. ‘A chair of state was provided for him,’ reported Walpole, ‘but he refused it; and sat by the princess on the couch, embraced and wept with her. He would not suffer Lady Augusta to kiss his hand, but embraced her, and gave it to her brothers, and told them, “They must be brave boys, obedient to their mother, and deserve the fortune to which they were born.”’32 It was a rare display of emotional sympathy from the king; but as the family sat huddled in their misery, they all knew that significant decisions must now be made about their future.

The most obvious solution would have been for the king to take over the upbringing and education of the young prince, bringing the boy to live with him at St James’s. At the same time, it might have been expected that the Duke of Cumberland would be made regent. As the king’s eldest surviving son, he would have been well placed to act for his father during his frequent absences in Hanover, and to be appointed guardian to the young George if the king had died while he was still a minor. In the event, none of these arrangements ever happened. They had been rendered politically impossible by the momentous events of 1745/46, the consequences of which were to have a profound effect on the lives of George, Augusta and indeed all of Frederick’s remaining family.

*

William, Duke of Cumberland, was loved by his parents with an intensity matched only by their disdain for his brother Frederick. Mirroring the actions of George I, it was rumoured that George II had once consulted the Lord Chancellor to discover if it would be constitutionally possible to disinherit his eldest son in favour of William. The disappointing answer he was said to have received did nothing to weaken the affection he felt for Cumberland, who shared many of his interests, particularly his passion for the army. Cumberland had been given all the military experience that Frederick persuaded himself he craved and had been denied. He was a capable soldier and at the age of only twenty-three was appointed captain general. ‘Poor boy!’ commented Walpole, ‘he is most Brunswickly happy with all his drums and trumpets.’33 When Charles Edward Stuart raised his standard in Scotland in 1745, Cumberland was the obvious candidate to put down a rebellion aimed directly at the survival of the Hanoverian dynasty. His reputation would never recover from the victory he won.

The possibility of regime change seemed a very real one as Bonnie Prince Charlie’s troops swept first through Scotland and then through northern England in the winter of 1745. As Carlisle, Lancaster and Preston fell, panic engulfed London. Even Horace Walpole was shaken out of his usual pose of ironic detachment, putting all his trust in the duke’s ‘lion’s courage, vast vigilance … and great military genius’.34 After Charles Stuart made the unexpected decision to turn back at Derby, Cumberland chased his army back to Scotland, where the two forces met on 16 April 1746 at Culloden. The duke’s victory over the exhausted Jacobites was total, and the aftermath of the battle exceptionally brutal, as Cumberland’s soldiers bayoneted wounded survivors. This was only a prelude to an extensive campaign of terror, intended by Cumberland to eradicate all possibility of another uprising. ‘Do not imagine,’ the duke wrote, ‘that threatening military execution and other things are pleasing to do, but nothing will go down without it. Mild measures will not do.’35 He was not alone in thinking extreme actions were called for. ‘I make no difficulty of declaring my opinion,’ declared Lord Chesterfield, ‘that the commander-in-chief should be ordered to give no quarter but to pursue the rebels wherever he finds ’em.’36 Cumberland’s troops pursued the defeated Scots into the glens and remote settlements of the Highlands, burning and murdering as they went, killing not just men of fighting age, but women, children, and even the cattle that supported them.

At first, Cumberland was fêted for the completeness of his victory. Handel composed See, the Conquering Hero Comes to mark his triumph; the duke was mobbed in the street, celebrated as the defender of constitutional monarchy. But as accounts began to arrive in London describing the methods by which he had achieved his success – and as the initial relief at the removal of the Jacobite threat began to fade – a sense of popular unease mounted. The atrocities appalled a public who, with the threat of a restored Stuart monarchy now behind them, did not feel liberty had been best protected by uncontrolled rape and murder. Simultaneously, suspicion of what Cumberland’s true intentions might be began to mount. At the head of a vicious and unstoppable army, what might he not attempt? Could he use it to break opposition as thoroughly in England as he had done in Scotland, and seize power for himself?

Frederick, who saw Cumberland’s success as a direct threat to him, did all he could to fuel hostility to his brother. He financed a pamphlet laying out in detail all the excesses committed by Cumberland’s troops, and his adviser Egmont wrote another, arguing that the emboldened duke’s next step would indeed be to mount a coup d’état. This was a complete fiction, but a very powerful one, that struck alarm into the hearts of otherwise rational politicians for nearly twenty years. In eighteen months, Cumberland was transformed in the public perception from conquering hero to ‘the Butcher’, a cruel German militarist with tyrannical ambitions and, unless his access to power was closely controlled, both the desire and the means to make them real.

So overwhelming was this scenario, even at the time of Frederick’s death five years after Culloden, that it made Cumberland unemployable in England. The king railed impotently against what he regarded as the traducing of his favourite, declaring that ‘it was the lies they told, and in particular this Egmont, about my son, for the service he did this country, which raised the clamour against him’; but he knew nothing could be done about it.37 He understood the political realities well enough to understand that Cumberland could never now be made regent. The disgraced duke bore his exclusion stoically in public – ‘I shall submit because the king commands it’ – but in private confessed himself deeply humiliated, wishing ‘that the name William could be blotted out of the English annals’.38

If he could not name Cumberland regent, the king had little choice but to appoint an otherwise most unlikely candidate, Augusta, who now held the title of princess dowager. And if she was thought competent to act in that capacity, he could hardly justify removing his heir from her control. Thus, against all expectation, the young Prince George was allowed to stay in the company of his mother. This decision was to have an extraordinary effect on the shaping of his character; as much as the premature death of his father, it was to determine the kind of man he became. Had he been exposed, while still a boy, to the worldly challenges of life at George II’s court, very different aspects of his personality might have emerged. Instead, he was allowed to retreat with Augusta into an increasingly remote and cloistered existence.

His mother’s intention was to protect him, and George – anxious and easily intimidated – was keen to be protected. He had responded to news of his father’s death with a sense of shock so profound that it was physical in its intensity. ‘I feel it here,’ he declared, laying his hand on his chest, ‘just as I did when I saw the two workmen fall from the scaffold at Kew.’39 He did not like his grandfather, whom he rightly suspected was irritated by his shyness and lack of confidence. (On one occasion, the king’s frustration may have taken more violent form; a generation later, walking round Hampton Court, George III’s son, the Duke of Sussex, mused: ‘I wonder in which one of these rooms it was that George II struck my father? The blow so disgusted him that he could never afterwards think of it as a residence.’40) But when George II arrived at Leicester House in the days after Frederick’s death, ‘with an abundance of speeches and a kind behaviour to the princess and the children’, his sympathy seemed so genuine that even the cautious prince was partially won over. He declared that ‘he should not be frightened any more with his grandpa’.41

Despite this, it is hard to believe that George II could ever have changed the habits of a lifetime and transformed himself into the steady, supportive father figure of which his heir stood in such deep need over the next few years. Certainly the prince did not think so. For all the king’s new-found concern, his timid grandson had no wish to test the depth of his solicitude by joining him at St James’s. He made it clear he preferred to live with his mother. Yet, although the prospect of staying with Augusta no doubt offered security to a young boy badly in need of solace, it was far from an ideal solution. The life Augusta made for her son, isolated from the world he would one day be expected to dominate, did nothing to prepare him for the role that his father’s death had made so terrifyingly imminent. The complicated politics that had ensured George remained in his mother’s care may not, in the long run, have done him much of a favour.

*

Until Frederick’s sudden death, the defining quality of Augusta, Princess of Wales, was her apparent passivity. She seemed to have no real personality of her own, but was entirely under the control of her husband. Hervey, who once memorably described her as ‘this gilded piece of royal conjugality’, claimed that she played no active role in his political life. Frederick, he reported, had once observed that ‘a prince should never talk to a woman of politics’ and that ‘he would never make himself the ridiculous figure his father had done in letting his wife govern him or meddle with business, which no woman was fit for’.42 George II, on the other hand, who always suspected there was more to his daughter-in-law than met the eye, used to declare: ‘You none of you know this woman, and none of you will know her until after I am dead!’43

The king was not wrong in alleging that Augusta was not quite the demure innocent she seemed. For all Frederick’s protestations, she was no stranger to his political ambitions during the late 1740s. She hosted the dinners at which he and his supporters thrashed out their strategies and engineered their alliances; she was discreet, trustworthy and, above all, unquestioningly loyal, identifying herself completely with her husband’s strategising. Significantly, it was to Augusta, and not to one of his trusted advisers, that Frederick entrusted his ‘Instructions’, encapsulating the programme he expected his eldest son to implement in due course, and it was she who was charged with explaining them to his heir and keeping them fresh in his mind. And after Frederick’s shocking demise, it was she who took brisk and immediate measures to destroy any incriminating material that might compromise his followers and his family.

As the historian John Bullion has shown, in the hours immediately following his death, she showed herself to be more of a politician than any of his dazed friends. While Frederick lay dead in the next room, she summoned Lord Egmont and outlined a decisive plan of action to be followed in the next few vital hours. ‘She did not know, but the king might seize the prince’s papers – they were at Carlton House – and that we might be ruined by these papers.’ She probably had in mind a document Frederick had drawn up in 1750 that was a blueprint for action in the event of the king’s death and described in some detail appointments that were to be made and policies followed. She gave Egmont the key to three trunks, told him to retrieve the papers and bring them back to her; she even gave him a pillowcase in which to carry them. When Egmont returned, she burnt the papers in front of him. Only then did she begin to consider what to do about her husband’s body, or inform the king of his death.44

Having dealt with the most pressing threat to her family’s security, she proceeded to manage her father-in-law too. When he arrived at Leicester House, ‘she received him alone, sitting with her eyes fixed: thanked the king much, and said she would write as soon as she was able; and in the meantime, recommended her miserable self and children to him’.45 Always pleased to be treated with the respect he thought he deserved, the king warmed to her submission, as she must have known he would. ‘The king and she both took their parts at once; she, of flinging herself entirely in his hands, and studying nothing but his pleasure; but minding what interest she got with him to the advantage of her own and the prince’s friends.’46 When she heard that the king had decided to allow George to stay with her, she did not forget to write and tell him how thankful she was.

Although Augusta was astute enough to have kept hold of her son, she had no idea what to do with him once she had him. She had no vision for his development, no sense of how best to equip him to face his destiny with confidence. She was not a strategic thinker; without imaginative leadership, Augusta’s instincts were always defensive. She had neither the desire nor the capacity to forge alliances or build networks of friendship and support for her son. Hers was an inward-looking nature, suspicious of those she did not know and habitually secretive. Dodington, who came to know her very well, thought the defining quality of her character was prudence, ‘not opening herself much to anybody, and of great caution to whom she opens herself at all’.47 As a result, her motives were often opaque, and her true feelings more so. Lord Cobham thought her ‘the only woman he could never find out; all he discovered about her was that she hated those she paid court to’.48

If she was an enigma, she was an increasingly sombre one. No longer obliged to accompany Frederick into the wider world, she quickly lost the habit of pleasure; she went nowhere and saw no one. But she did not appear to miss the life that had been taken from her with such cruel suddenness. Instead, she seemed to relish the opportunity to dispense with the trappings of her old existence, and emerge as a sober woman of early middle age, unencumbered now by the obligation to please or conciliate anyone but herself. Nothing illustrates more starkly the gulf between these two versions of Augusta than two contrasting portraits. In 1736, she was painted in a conventionally fashionable pose. Overwhelmed by the stiff ornateness of her dress, she is a tiny doll-like figure, rigid and stranded in the gloom of an oppressive grey interior. Of her personality, there is no sense at all. In 1754, when Augusta chose her own artist, the result could not have been more different. Jean-Etienne Liotard’s portrait is not an image designed to flatter. Augusta is simply dressed; she wears no jewellery, and her hair is pulled back sharply from her forehead. Its defining quality is its cool candour. Augusta’s gaze is wary; her whole posture suggests a guarded, watchful reticence. She does not seem a woman eager for enjoyment or delight; and it is perhaps possible to read in her expression a hint of the debilitating combination of anxiety and suspicion with which she came to view the world in the long years of her widowhood.

These were not the happiest qualities on which to build a family life, and it must have been quickly apparent to Augusta’s children that, as the halo of their father’s warmth and sociability dimmed, their world grew inexorably chillier. The amateur theatricals, the compulsory team sports, the trips and treats and jokery, the noise and lively bustle of their father’s daily round all gradually ebbed away. They were replaced by a carefully cultivated seclusion, in which all the pleasures were small ones.

One of the few people allowed to intrude into this increasingly remote and withdrawn existence was George Dodington, whom Augusta adopted as chief confidant after her husband’s death. A much-tried member of Frederick’s entourage, Dodington’s greatest asset was his understanding of the practical business of politics, drawn from a lifetime of holding office and the management of parliamentary interests, although he had many other sterling qualities: he was loyal, witty and humane, an ugly man with a complicated love life and a naive enthusiasm for extravagant grandeur. Walpole described his house in Hammersmith as a monument to rich, bad taste, crammed full of marble busts and statues, and dominated by a fireplace decorated with marble icicles. It is not hard to see why Frederick, with his predilection for the eccentric, should have enjoyed his company. That Augusta too soon came to value and rely upon him is further testament to her carefully concealed political acumen. Beneath his unprepossessing exterior, Dodington nurtured a sharp mind and a wealth of experience. He was an excellent ally for a woman who believed herself more or less friendless, a seasoned adviser who could help her navigate her way through the difficulties that lay ahead. Perhaps Augusta also recognised in him some of the warmth and conviviality that was in such short supply elsewhere in her household.

Dodington clearly missed his late patron’s relaxed expansiveness. He often struggled to penetrate Augusta’s ingrained reticence, but did all he could to support and encourage her. He recorded his somewhat stuttering progress in his diary, a rueful chronicle of his efforts to persuade Augusta to adopt what he saw as politic courses of action. It was not an easy task. He soon saw there was no chance at all that Frederick’s death might have opened the way for a serious reconciliation with the rest of the royal family. Beneath the blandly compliant surface she presented to her in-laws throughout her married life, Augusta hid a settled dislike and disrespect for all her Hanoverian relations which was evident from the earliest days of her widowhood. In 1752, she and Dodington were enjoying a gossip about the Dorset family. Dodington opined that ‘there were oddnesses about them that were peculiar to that family, and that I had often told them so. She said that there was something odd about them, and laughing, [she] added that she knew but one family that was more odd, and she would not name that family for the world.’49 It was a rare moment of playfulness – and the only instance of Augusta’s laughter in the whole of Dodington’s diary. Her antipathy was usually expressed with far greater resentment, seen most starkly in her attitude to the king. As Frederick’s wife, she had shared in all the humiliations that had been heaped upon him by his father; then, for over a decade, she had witnessed all her husband’s attempts to harass and embarrass George through the medium of politics. Her husband’s hostility and suspicion had defined her attitude to her father-in-law for twenty years, and continued to do so long after he was dead.

Augusta knew these were views that could have no outward expression. She told Dodington she fully understood ‘that, to be sure, it was hers and her family’s business to keep well with the king’.50 In public, she assiduously cultivated the role of dutiful daughter-in-law, obedient and tractable; but in private, she had nothing but contempt for her father-in-law. She was bitterly angry that George had refused to settle Frederick’s debts, which she considered a slight to his posthumous reputation, and furious when he refused to release to her the revenues from the Duchy of Cornwall that he had claimed for himself after the prince’s death. As she described how she had berated and harangued the king on the vexed subject, Dodington’s politician’s spirits sank; he was not surprised to hear that George rarely visited now. His absence did nothing to make Augusta’s heart grow fonder. Over a period of six months, Dodington heard her speak favourably of the king only once, and considered it so remarkable that he made a special note of it.

She was equally dismissive of the Duke of Cumberland, whom she referred to with heavy irony as ‘her great, great fat friend’, and who had also refused to assist in paying Frederick’s debts.51 She rebuffed all his attempts to build a friendship with his nephew. Augusta rarely missed an opportunity to mock or belittle the duke. ‘The young Prince George had a great appetite; he was asked if he wanted to be as gross as his uncle? Every vice, every condescension was imputed to the duke, that the prince might be stimulated to avoid them.’52 More seriously, Augusta accepted absolutely the popular belief – encouraged so assiduously by her husband – that Cumberland harboured unconstitutional designs on the throne. She drilled these into Prince George, who, as the sole obstacle standing in the way of such ambitions, regarded his uncle with nervous trepidation. Once, during a rare meeting alone with his nephew, Cumberland pulled down some weapons he had displayed on his wall to show the young prince; George ‘turned pale, and trembled and thought his uncle was going to murder him’. Cumberland was horrified and ‘complained to the princess of the impressions that had been instilled into the child against him’.53 It was not until after he succeeded to the throne that George shook off the distrust of his uncle nurtured in him by his mother.

Augusta soon found herself without friends. She could not seek the support of opposition politicians except at the risk of provoking the king to remove the prince from her care, and she was too deeply imbued with her husband’s opinions to seek allies from within the royal family. It was a tricky situation for which Dodington could see no immediate resolution. He begged Augusta not to act precipitately, and she assured him that she would do nothing rash and had made no dangerous alliances, insisting that she had ‘no connexions at all’. Dodington found this only too easy to believe. Isolated as she was, without friends, family or supporters, there was little he could offer her except patience, meaning she had no choice but to wait for the king to die. In the privacy of his diary, Dodington was more pessimistic about her prospects, recording his stark belief that she must ‘become nothing’.

*

As Frederick’s family drifted gradually but inexorably away from both their surviving royal relations and the active political heartland, they had only themselves to rely upon for company. In the mid-1750s, all Augusta and Frederick’s children were still alive; fourteen years separated the eldest, Augusta, from the youngest, baby Caroline, born five months after her father’s death and named to please her grandfather. In the 1930s, the historian Romney Sedgwick commented that ‘as a eugenic experiment, the marriage could not be considered a success’. His remark, though callous, contained an element of truth. Five of Frederick and Augusta’s offspring died either in childhood or in their twenties, and two were sickly from birth. Elizabeth, the second daughter, was thought by Walpole to have been the most intelligent of all the family – ‘her parts and applications were extraordinary’ – but her figure ‘was so very unfortunate that it would have been impossible for her to be happy’.54 She died in 1759, probably from appendicitis. Louisa, the third daughter, died at nineteen, having suffered from such bad health that even her aunt, Princess Amelia, ‘thought it happier for her that she was dead’.55 The youngest son, Frederick, ‘a most promising youth’, according to Walpole, died at sixteen of consumption.

Prince George was considered to be one of the best looking of Frederick’s family; he was also, as a child and a young man, among the healthiest. His elder sister Augusta, whose grasp on life had seemed so tenuous after the thoughtless theatrics surrounding her birth, grew into an equally resilient child, although her looks were never much admired. Walpole thought ‘she was not handsome, but tall enough, and not ill-made; with the German whiteness of hair and complexion so glaring in the royal family, and with their thick yet precipitate Westphalian accent’.56 She was eager, lively and boisterous, resembling her brother Edward in her love of a joke. William, Duke of Gloucester, the third brother, was as fair as Augusta and Edward, but of a very different disposition. Walpole, who knew him well, summed him up as ‘reserved, serious, pious, of the most decent and sober deportment’. He closely resembled his eldest brother, whose favourite sibling he later became. Henry, who became Duke of Cumberland after his uncle’s death, was small like his father ‘but did not want beauty’. He had, however, ‘the babbling disposition of his brother York, though without the parts or condescension of the latter’. His youth, concluded Walpole severely, ‘had all its faults, and gave no better promises’.57 The toddler Caroline was remarkable at this stage only for her beauty; the ‘German whiteness’ that contemporaries found so ‘glaring’ in her brothers and sisters had in her become a golden blonde. Taken together with her blue eyes and round, pink face, she was by far the prettiest of the family.

Dodington’s diary is peppered with glimpses of ‘the children’, flitting silently round the edges of the world in which he and Augusta occupied centre stage. Always mute, they move as an undifferentiated royal pack. ‘The children’ are sent to prayers; ‘the children’ come in to dine; ‘the children’ retire. Occasionally, the older siblings emerged from the group and joined their mother in simple, family pleasures and games. Dodington was excessively proud of his occasional invitations to join the family in such informal moments, and recorded them with palpable satisfaction. In November 1753, he went to Leicester House ‘expecting a small company and a little music; but found no one but Her Royal Highness. She made me draw up a stool, and sit by the fire with her. Soon after came the Prince of Wales and Prince Edward and then the Lady Augusta, all quite undressed, and took their stools and sat round the fire with us. We sat talking of familiar occurrences of all kinds till between 10 and 11, with ease and unreservedness and unconstraint, as if one had dropped into a sister’s house that had a family to pass the evening.’

Gentle, unforced intimacy of this kind represented Augusta’s household at its best. But while Dodington strongly approved of such warm domestic scenes, he knew in his heart that they were only part of what was required to prepare the older boys for their future lives. He added a wistful postscript to his lyrical description of his quiet night at home with royalty. ‘It was much to be wished,’ he wrote, ‘that the princes conversed familiarly with more people of a certain knowledge of the world.’58 At a time when George should have been learning how to conduct himself in society, he was utterly removed from it. By 1754, when George was sixteen, even Augusta had begun to worry that the narrow existence she had created for her son was failing him. She confessed to Dodington that she too ‘wished he saw more company – but whom of the young people were fit?’59 She recognised that her eldest son needed more experience of life, but could not reconcile this with her increasingly dark vision of what lay beyond the secure walls of home. For Augusta, whose character took on an ever bleaker cast in the years after her husband’s death, the world was a wicked and threatening place and it was her first duty to protect her children from its wiles. Wherever she looked, she saw only moral bankruptcy. She complained at great length to Dodington of the ‘universal profligacy’ of the youthful aristocrats who might, in other circumstances, have become her children’s friends. The men were bad enough, but the women were even worse, ‘so indecent, so low, so cheap’.60 Beyond the inner circle of the family, everyone’s behaviour, motives and desires were suspect; no one was really to be trusted. Exposed to temptation, even her own sons might not have the inner strength to resist it. The preservation of an untested virtue, secured by isolation and retirement, was thus the key foundation of their upbringing. ‘No boys,’ commented William, Duke of Gloucester, in middle age, ‘were ever brought up in a greater ignorance of evil than the king and myself … We retained all our native innocence.’61 In the end, Augusta’s instinctual desire to protect her children from the lures of the world proved stronger than her rational understanding that they must one day learn to master it.

If Prince George’s social and family life did little to equip him for the future, he was equally unprepared in almost every other practical dimension of kingship. As a young man, he was bitter about the failings he believed had left him so exposed. ‘I will frankly own,’ he wrote in 1758, ‘that through the negligence, if not wickedness of those around me in earlier days … I have not that degree of knowledge and experience of business one of my age might reasonably have acquired.’62 His formal education had certainly been a haphazard affair. After Frederick’s death, it was underpinned by no coherent plan and driven by political considerations as much as by the desire to equip the boy with a foundation of useful knowledge. The king had replaced George’s tutors with his own appointees; only George Scott, who did most of the actual teaching, survived as part of the new team. As the prince’s governor, George II appointed his friend Simon, Earl Harcourt, a loyal courtier whose principal task was to ensure that the prince was encouraged neither to venerate nor to follow the policies of his dead father. He was otherwise undistinguished, memorably described by Walpole as ‘civil and sheepish’.63 Thomas Hayter, Bishop of Norwich, filled the role of preceptor. His pupil had nothing but contempt for him, describing him in later life as ‘unworthy … more fitted to be a Jesuit than an English bishop’.64 A third new appointment was Andrew Stone, who became sub-governor. Stone, like Harcourt, was a political choice; he was the fixer and general factotum of the Duke of Newcastle, who served regularly as George II’s first minister, and could be expected to pass back to St James’s detailed reports of events at Leicester House.

Under this top-heavy array, George and his brother Edward were set to work. Their lessons began at seven in the morning, and ranged, as they had always done, well beyond the traditional curriculum. However, the more modern subjects – including science, which George particularly enjoyed – did not displace the traditional concentration on the classics. Caesar’s Commentaries remained a familiar if unwelcome feature of the princes’ daily routine, much to George’s frustration. ‘Monsieur Caesar,’ he wrote in the margins of one of his laborious translations, ‘je vous souhaite au diable.’ (‘I wish you to hell.’65) As his later life was to demonstrate, George had a lively mind, and as an adult would find pleasure in a wide range of intellectual pursuits; but he found little to engage his imagination in what he was taught as a boy. He lacked the aptitude to master ancient languages, and was, in general, poor at rote learning. His fascination for practical and mechanical tasks was regarded as further evidence of his intellectual dullness. Only in music did he shine, playing the German flute with self-absorbed pleasure. All the siblings were accomplished amateur musicians, the girls singing and playing the harpsichord. The love of music was one of the few passions he shared with his father, and one which would outlast his sanity. In all other areas of educational endeavour, especially those that required feats of memory, George was generally regarded as a failure, his apathy and inattention exasperating his instructors.

Augusta knew, as did almost everyone else in the political world, that her eldest son was not making the progress expected of him: ‘His education had given her much pain. His book-learning she was no judge of, but she supposed it small or useless.’66 She thought her sons had not been well served by their instructors. Bishop Hayter may have been ‘a mighty learned man’, but he did not seem to Augusta ‘to be very proper to convey knowledge to children; he had not the clearness she thought necessary … his thoughts seemed to be too many for his words’.67 She told Dodington that she had repeatedly attempted to challenge Lord Harcourt directly about what was happening, but he simply avoided her. She finally cornered him one night at St James’s, ‘and got between the door and him, and took him by the coat’; even then the slippery earl escaped her grasp with a platitude. She disliked Harcourt, not only for his elusiveness, but because he ‘always spoke to the children of their father and his actions in so disrespectful a manner as to send them to her almost ready to cry’.68

Stone, in contrast, ‘always behaved very well to her and the children and though it would be treason if it were to be known, always spoke of the late prince with the greatest respect’.69 But even he seemed to have a curious idea of what was required of him. ‘She once desired him to inform the prince about the constitution,’ wrote Dodington, ‘but he declined it, to avoid giving offence to the Bishop of Norwich. That she had mentioned it again, and he had declined it, as not being his province.’ When Dodington asked Augusta what Stone’s province was, ‘she said she did not know, she supposed to go before him upstairs, to walk with him, sometimes seldomer to ride with him and then to dine with him’.70

George’s tutors had reason to be nervous when called upon to offer interpretations of the constitution to the heir to the throne. At the end of 1752, Harcourt and Hayter turned on their colleagues Stone and Scott and accused them of Jacobite sympathies, claiming they were covertly indoctrinating George with absolutist principles. They offered no real evidence for their charges, and could persuade neither the king nor his first minister, Newcastle, to believe them. Both promptly resigned, but the recriminations surrounding the affair dragged on for over a year, and were not resolved until Stone had appeared before the Privy Council and the matter had been raised in the House of Lords. It was easy for Dodington to declare with passion that ‘what I wanted most was that his Royal Highness should begin to learn the usages and knowledge of the world; be informed of the general frame and nature of government and the constitution, and the general course and manner of business’.71 But, as the cautious Stone had understood when he refused Augusta’s direct invitation to do just that, attempting the political education of princes was a far riskier undertaking than teaching them Latin.

With the departure of Harcourt and Hayter, the king was determined to make one last effort to turn his fourteen-year-old grandson into the kind of heir he thought he deserved. Prince George’s hesitant and self-conscious appearances at the formal Drawing Rooms did not impress his grandfather, who had forgotten many of the tender professions he had made at the time of Frederick’s death. Unless taken in hand, he feared the prince would be fit for nothing but to read the Bible to his mother. He approached James, Earl Waldegrave, who had been a Lord of the Bedchamber in his household, and asked him to become the prince’s new governor. Confident, experienced and expansive, Waldegrave was a very different character from the ineffectual Harcourt, and his sophisticated presence introduced an unfamiliar flavour into Augusta’s circle. At first, everyone seemed to welcome both it and him, and Waldegrave used this early advantage to effect something of a revolution in the prince’s education. He recognised immediately that the most important task was to engage George’s fitful attention, and sought to do this by offering him a vision of knowledge that went beyond the traditional forms of learning his pupil found so unengaging. ‘As a right system of education seemed impossible,’ Waldegrave recalled in his Memoirs, ‘the best which could be hoped for was to give him true notions of common things; to instruct him by conversation, rather than books; and sometimes, under the disguise of amusement, to entice him to the pursuit of more serious studies.’72

Waldegrave thought that George might work harder if he enjoyed himself more. Unlike any of his previous instructors, he was convinced that beneath the habitual indolence, the prince had potential. The present glaring shortcomings in his character were, Waldegrave believed, less a reflection of his true nature and more the inevitable product of the circumscribed life he led: ‘I found HRH uncommonly full of princely prejudices, contracted in the nursery and improved by the society of bedchamber women and pages of the back-stairs.’73 Wider experience of the world might cure many of the faults that others had found so intractable.

As time went on, however, it became clear to Waldegrave that the kind of change he advocated – a relaxation of the regime of seclusion, a more active participation in society – would never be countenanced by Augusta. For all her anxieties about her eldest son’s education, she would not sacrifice any of her own prejudices to see it improved. She did not expect her authority to be challenged by her son’s governor. She explained to Dodington that she considered the post – and Waldegrave, while he occupied it – ‘as a sort of pageant, a man of quality for show, etc.’.74 Faced with her blank resistance, Waldegrave’s new measures ran slowly but steadily into the ground. Although he was supported in his endeavours by ‘men of sense, men of learning and worthy good men’, Waldegrave eventually concluded he could do nothing to make a real difference: ‘The mother and the nursery always prevailed.’75

By the mid-1750s, George’s formal education had done little more than confirm in the self-conscious boy an even greater sense of his own shortcomings. Morbidly aware of his faults, especially those of ‘lethargy’ and ‘indolence’ with which he was so often charged, he seemed incapable of rousing himself to do anything about them. He had, thought Waldegrave, ‘a kind of unhappiness in his temper, which if it be not conquered before it has taken too deep a root, will be a source of frequent anxiety’. The prince’s apparent preference for solitude concerned Waldegrave, especially as he suspected the boy chose to be alone the better to contemplate his misery: ‘he becomes sullen and silent and retires to his closet, not to compose his mind by study, or contemplation, but merely to indulge the melancholy enjoyment of his own ill humour’.76 He had no friends except his brother Edward, to whom he was very close. To everyone else, he revealed nothing of himself. The retired life he and his mother shared had certainly not forged a strong emotional bond between them. When Dodington asked her ‘what she took the real disposition of the prince to be’, Augusta replied that Dodington ‘knew him almost as well as she did’.77

As he drifted irrevocably towards a destiny that terrified him, George retreated further and further into a private world of remote introspection. Transfixed with apprehension by the prospect before him, lethargy overwhelmed him. Neither his tutors nor his family knew what to do about it, or understood that his much-criticised indolence was less a sign of laziness than a strategy to avoid engaging with a future he knew he could not avoid. By the time he was sixteen, in 1754, he had erected around himself a tough carapace of emotional detachment which no one could penetrate. But George’s life was about to be transformed by someone who would instil in him a new vision of who he was; and, for the first time, offer the anxious boy an inspirational idea of what he might become. He encountered the man who would change his life for ever.

*

John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, was a well-connected aristocrat related to some the grandest names in Scottish politics, including the powerful Dukes of Argyll. For a man whose career was so dominated by the fact of his Scottishness, he spent a surprising amount of his early life in England. He was educated at Eton alongside Horace Walpole, who was later to paint such a malign picture of him in his Memoirs of the Reign of King George III. Bute married early, and for love: in 1736, at the age of twenty-three, he eloped with the only daughter of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. The girl’s furious father refused to make any financial provision for his disobedient daughter and her new husband. When his irascible father-in-law died some twenty years later, Bute inherited all his money and became extremely rich; but as a young man, he was always short of funds. Contemporaries were certain that only poverty – or ‘a gloomy sort of madness’ – could have induced him to take up residence on the remote island that bore his name. In the years before the Romantics induced the literate public to admire the wilderness, it was assumed no sensible modern man would choose to live so far from civilisation. Bute’s critics, of whom even in his earliest days there were many, asserted that his personality was ideally suited to his faraway, chilly home. ‘His disposition,’ one remarked, ‘was naturally retired and severe.’78 Others mocked his pomposity and high opinion of himself, his ‘theatrical air of the greatest importance’, his ‘look and manner of speaking’ which, regardless of the subject, ‘was equally pompous, slow and sententious’.79 On his island, Bute pursued the literary and scientific studies that were the mark of the aristocratic eighteenth-century intellectual, including ‘natural philosophy, mines, fossils, a smattering of mechanics, a little metaphysics’. His enemies claimed that this was all typical self-aggrandisement and that he had in fact ‘a very false taste in everything’.80 It was true that Bute was something of an intellectual dilettante, but in the field of botany, which was his great passion, he possessed real authority. His nine-volume Botanical Tables Containing the Families of British Plants, completed in 1785, created a system of classification that was a genuine contribution to scholarship.

In 1746, Bute left his island and headed south, hoping perhaps to improve his financial prospects. Once in London, he was soon noticed, but it was not the power of his mind that attracted attention. ‘Lord Bute, when young possessed a very handsome person,’ recalled the politician and diplomat Nathaniel Wraxall, ‘of which advantage he was not insensible; and he used to pass many hours a day, as his enemies asserted, occupied in contemplating the symmetry of his own legs, during his solitary walks by the Thames.’81 Bute’s portraits – in which his legs are indeed always displayed to advantage – confirm that he was a very attractive man. Tall, slim and with a dark-eyed intensity of expression, it is not hard to see why he was so sought after. It may have been his looks that caught the eye of the Prince of Wales. It was said that Bute first met Frederick at Egham races, when the prince invited him in from a rainstorm to join the royal party at cards. Soon he was a regular attendee at all the prince’s parties, and had unbent sufficiently to play the part of Lothario in one of Frederick’s private theatrical performances. The prince seemed to enjoy his company, and Bute was admitted to the inner circle of his court. Walpole asserted that Frederick eventually grew tired of Bute’s pretensions, ‘and a little before his death, he said to him, “Bute, you would make an excellent ambassador in some proud little court where there is nothing to do.”’82 But whatever his occasional frustrations, Frederick thought enough of the earl to make him a Lord of the Bedchamber in his household, and it was only the prince’s sudden demise that seemed to put an end to Bute’s ambitions, as it did to those of so many others.

After Frederick’s death, Bute stayed in contact with his widow. Augusta shared his botanical interests, and he advised her on the planting of her gardens at Kew. He is never mentioned in Dodington’s diary, perhaps because Dodington correctly identified him as a rival for Augusta’s confidence. As the years passed, Bute’s influence grew and grew, until, by 1755, he had supplanted Dodington and all other contenders for the princess’s favour. He had also won over her son, and without telling anyone, least of all the king, Augusta quietly instructed Bute to begin acting as George’s tutor. For all his experience in the ways of courts, Waldegrave, the official incumbent, seems to have had no idea what was happening until it was too late. Once he realised just how thoroughly he had been supplanted, Waldegrave was determined to leave with as much dignity as he could muster. The king pressed Waldegrave to stay. He was resolutely opposed to the inclusion of Bute – an intimate of Frederick’s – in the household of his grandson, particularly in a position of such influence; but Waldegrave knew there was nothing to be done. In 1756, the prince reached the age of eighteen and could no longer be treated as a child. Reluctantly, the king bowed to the inevitable, and Bute was appointed Groom of the Stole, head of the new independent establishment set up for George. To show his displeasure, the king refused to present Bute with the gold key that was the badge of his new office, but gave it to the Duke of Grafton – who slipped it into Bute’s pocket and told him not to mind.

When Horace Walpole wrote his highly partisan account of the early reign of George III, he maintained that there was far more to Bute’s appointment than anyone had realised at the time; it was, he claimed, the opening act in a plot aimed to do nothing less than suborn the whole constitution. In Walpole’s version of events, Augusta and Bute – ‘a passionate, domineering woman and a favourite without talents’ – conspired together to bring down the established political settlement. They intended first to indoctrinate the supine heir with absolutist principles, and then to marginalise him by ensuring his isolation from the world. All this was to be achieved in the most gradual and surreptitious manner. Ignorant and manipulated, George would remain as titular head of state; but behind him, real power would reside in the hands of Bute and Augusta. To add an extra frisson to a story already rich in classical parallels, Walpole insisted that Augusta and Bute were lovers, ‘his connection with the princess an object of scandal’. Elsewhere he was more blunt, declaring: ‘I am as much convinced of an amorous connexion between Bute and the princess dowager as if I had seen them together.’83

Related with all the passion he could muster, in Walpole’s hands this proved to be a remarkably potent narrative. For nearly two hundred years, until interrogated and revised by the work of twentieth-century historians, it was to influence thinking about George’s years as Prince of Wales and as a young king; and the reputations of Bute and Augusta are still coloured by Walpole’s bilious account of their alleged actions and motives. But in writing the Memoirs, Walpole’s purpose was scarcely that of a disinterested historian. First and foremost, he wrote to make a political point. Walpole was a Whig, passionately opposed to what he saw as the autocratic principles embraced by his Tory opponents, who, he had no doubt, desired nothing so much as to restore the pretensions and privileges of the deposed Stuarts. He was, he said, not quite a republican, but certainly favoured ‘a most limited monarchy’, and was perpetually on the lookout for evidence of plots hatched by the powerful and unscrupulous to undermine the hard-won liberties of free-born Britons. To that extent, the Memoirs, couched throughout in a tone of shrill outrage quite unlike Walpole’s accustomed smooth, ironic style, are best considered as a warning of what might happen rather than an account of what did – a chilling fable of political nightmare designed to appal loyal constitutionalists. Less portentously, Walpole also wrote to pay off a grudge. He considered he had been wronged by Bute, who had refused to grant him a sinecure Walpole believed he was owed: ‘I was I confess, much provoked by this … and took occasion of fomenting ill humour against the favourite.’84

Much of what resulted from this incendiary combination of intentions was simply nonsense, and often directly contradicted what Walpole had himself written in earlier days. In truth, there was no plot; Augusta was not ‘ardently fond of power’; neither she nor Bute was scheming to overturn the constitution; and it is extremely unlikely that they were lovers. But if the central proposition of Walpole’s argument was a fiction, that did not mean that everything he wrote was pure invention. The Memoirs exerted such a powerful appeal because Walpole drew on existing rumours that were very widely believed at the time; and because, sometimes, beneath Walpole’s wilder assertions there lay buried a tiny kernel of truth.

Thus, Walpole seemed on sure ground when describing the isolation in which George had been brought up, and the extraordinary precautions taken to keep him away from wider intercourse with the world. He was correct in his assertion that much of this policy had been driven by Augusta. He was wrong about her motives – the extreme retirement she imposed on her son was a protective cordon sanitaire, not a covert means of dominating him – but the prince’s isolation was observable to everyone in the political world, and of as much concern to Augusta’s few allies as it was to her enemies. Walpole was also right to assert that within the secluded walls of Kew and Leicester House, the future shape of George’s kingship was indeed the subject of intense discussion; but these reflections were directed towards an outcome very different from Walpole’s apocalyptic image of treasonous constitutional conspiracy. Finally, he was accurate in his suspicion that there was a passionate relationship at the heart of the prince’s household. But it was not, in fact, the one he went on to describe with such relish.