Читать книгу Curse of the Mistwraith - Janny Wurts, Janny Wurts - Страница 14

III. EXILE

ОглавлениеWho drinks this water

Shall cease to age five hundred years

Yet suffer lengthened youth with tears

Through grief, death’s daughter.

inscription, Five Century Fountain

Davien, Third Age 3140

The crown prince of Amroth awoke to a nightmare of buffeting surf. Muddled, disoriented and unaccountably dizzy, he discovered that he lay face-down on the floorboards of an open boat. The fact distressed him: he retained no memory of boarding such a craft. Through an interval of preoccupied thought, he failed to uncover a reason for an ocean voyage of any kind.

Lysaer licked his lips, tasted the bitter tang of salt. He felt wretched. His muscles ached and shivered and his memories seemed wrapped in fog. The bilge which sloshed beneath his shoulder stank of fish; constellations tilted crazily overhead as the boat careened shoreward on the fist of a wave.

The prince shut his teeth against nausea. Frustrated by the realization that something had gone amiss, he tried to push himself upright. A look over the thwart might at least identify his location. But movement of any kind proved surprisingly difficult; after two attempts, he managed to catch hold of the gunwale. The boat lurched under him. A stranger’s muscled arm bashed his fingers from the wood, and he tumbled backward into darkness…

The prince roused again as the boat grounded. Gravel grated against planking and voices called in the night. The craft slewed, caught by the drag of a breaker. Lysaer banged his head on the sharp edge of a rib. Shouts punched through the roar of the waves. Wet hands caught the boat, dragged her through the shallows and over firm sand to the tidemark. The bearded features of a fisherman eclipsed the stars. Then, callously impatient, two hands reached down and clamped the royal wrists in a grip that bruised. Limp as a netted fish, Lysaer felt himself hauled upright.

‘D’ye think the Rauven mage would care if we kept the jewels on ‘im?’ said a coarse male voice.

The prince made a sound in protest. His head whirled unpleasantly and his stomach cramped, obscuring an unseen accomplice’s reply. The grip on him shifted, then tightened, crushing the breath from his lungs. Lysaer blacked out once more as his captors dragged him from the boat.

His next lucid impression was an inverted view of cliffs silhouetted against the sea. Breakers and sky gleamed leaden with dawn. Slung like a sack across a back clad in oilskins, Lysaer shut his eyes. He tried desperately to think. Facts slipped his grasp like spilled beads, and his train of thought drifted; yet one fragment of memory emerged and yielded a reason for his confusion. Whatever drug his abductors had used to subdue him had not entirely worn off. Although the effects were not crippling, the prince felt inept as a newborn.

His captor slipped. A bony shoulder jarred Lysaer’s stomach. Consciousness wavered like water-drowned light. Shale rattled down a weedy slope as the man recovered his footing. Then his accomplice gripped the prince, and the sky spun right side up with a sickening wrench. Hefted like baled cargo, Lysaer felt himself bundled into a cloak of rancid, oiled wool. He twisted, managed to keep his face uncovered. But clear sight afforded no advantage. High overhead rose the chipped arch of an ancient stone portal; between the span swirled a silvery film, opaque as hot oil spilled on glass. The proximity of unnatural forces raised gooseflesh on Lysaer’s skin. Shocked to fear and dread, the prince recognized the Worldsend Gate.

He struggled violently. Too late he grasped the need to escape. His enemies raised him with merciless force, cast him headlong into mother-of-pearl whose touch was ice and agony. Lysaer screamed. Then the shock of the Gate’s forces ripped his mind to fragments. He plunged into fathomless dark.

The crown prince of Amroth roused to the sting of unbearable heat. Bitter dust dried the tissues of his nostrils at each breath and strange fingers searched his person, quick and furtive as rats’ feet. Lysaer stirred. The invading hands paused, then retreated as the prince opened his eyes.

Light stabbed his pupils. He blinked, squinted and through a spike of cruel reflection, made out the blade of his own dagger. Above, the eyes of Arithon s’Ffalenn appraised him from a face outlined in glare.

‘We’re better matched this time, brother.’ The bastard’s voice was rough, as though with disuse. Face, hands and the shoulder underneath his torn shirt showed flesh frayed with scabs and congested still with the purpled marks of abuse.

Sharply aroused from his lethargy, Lysaer scrambled upright. ‘What are you waiting for? Or did you hope to see me beg before you cut my throat?’

The blade remained still in Arithon’s hand. ‘Would you have me draw a brother’s blood? That’s unlucky.’

The words themselves were a mockery. A wasteland of dunes extended to an empty horizon. Devoid of landmark or dwelling, red, flinty sands buckled under shimmering curtains of heat. No living scrub or cactus relieved the unrelenting fall of white sunlight. The Gate’s legacy looked bleak enough to kill. Stabbed by grief that his royal father’s passion for vengeance had eclipsed any care for his firstborn, Lysaer clung wretchedly to dignity. Shaken to think that Amroth, his betrothed, every friend, and all of the royal honour that bound his pride and ambition might be forever reft from him, he drew breath in icy denial. ‘Brother? I don’t spring from pirate stock.’

The dagger jumped. Blistering sunlight glanced off the blade; but Arithon’s tone stayed inhumanly detached. ‘The differences in our parentage make small difference, now. Neither of us can return to Dascen Elur.’

‘That’s a lie!’ Rejecting the concept that his exile might be permanent, Lysaer gave way to hostility. ‘The Rauven sorcerers would never permit a favoured grandson to wither in a desert. They’ll reverse the Gate.’

‘No. Look again.’ Arithon jerked his head at the iron portal which arched behind. No curtain of living force shimmered there: the flaking, pitted posts framed only desert. Certainty wavered. This gate might truly be dead, sealed ages past against a forgotten threat, and beyond any power of the Rauven mages to restore. Lysaer battled shattering panic. The only living human who remained to take the blame was the s’Ffalenn bastard who crouched behind a knife in studied wariness.

‘You don’t convince me. Rauven spared you from execution.’ He paused, struck cold by another thought. ‘Or did you weave your shadows to shape that sending of the queen as a plot to seek your own vengeance?’

The blade hung like a mirror in the grip of dirty fingers; inflectionless, Arithon said, ‘The appearance of the lady and your presence here were not of my making.’ He shrugged to throw off wry bitterness. ‘Your drug and your chains left small room for personal scores.’

But the baiting of the king had been too bloodlessly thorough to inspire s’Ilessid trust. ‘I dare not believe you.’

‘We’re both the victims of bloodfeud,’ Arithon said. ‘What’s past can’t be changed. But if we set aside differences, we have a chance to escape from this wasteland. ’

As crown prince, Lysaer was unaccustomed to orders or bluntness; from a s’Ffalenn whose wretched misfortune might have been arranged to deprive a kingdom of its rightful heir, the prospect of further manipulation became too vicious to bear. Methods existed to disarm a man with a dagger. Sand warmed the prince’s bootsoles as he dug a foothold in the ground. ‘I don’t have to accept your company.’

‘You will.’ Arithon managed a thin smile. ‘I hold the knife.’

Lysaer sprang. Never for an instant off his guard, Arithon fended clear. He ducked the fingers which raked to twist his collar into a garrotte. Lysaer changed tack, closed his fist in black hair and delivered a well-placed kick. The Master twisted with the blow and spun the dagger. He struck the prince’s wristbone with the jewelled pommel. Numbed to the elbow by a shooting flare of pain, Lysaer lost his grip. Cat-quick in his footwork, Arithon melted clear.

‘I could easily kill you,’ said the hated s’Ffalenn voice from behind. ‘Next time remember that I didn’t.’

Lysaer whirled, consumed by a blind drive to murder. Arithon evaded his lunge with chill poise. Leary of the restraint which had undone Amroth’s council, the prince at once curbed his aggression. Despite his light build, the bastard was well trained and fast; his guileful cleverness was not going to be bested tactlessly.

‘Lysaer, a gate to another world exists in this desert,’ the Master insisted with bold authority. ‘Rauven’s archives held a record. But neither of us will survive if we waste ourselves on quarrelling.’

Caught short by irony, the prince struck back with honesty. ‘Seven generations of unforgiven atrocities stand between us. Why should I trust you?’

Arithon glanced down. ‘You’ll have to take the risk. Have you any other alternative?’

Alien sunlight blazed down on dark head and fair through a wary interval of silence. Then a sudden disturbance pelted sand against the back of Lysaer’s knees. He whirled, startled, while a brown cloth sack bounced to rest scarcely an arm’s reach from him. The purple wax that sealed the tie strings had been fixed with the sigil of Rauven.

‘Don’t touch that,’ Arithon said quickly.

Lysaer ignored him. If the sorcerers had sent supplies through the Gate, he intended to claim them himself. He bent and hooked up the sack’s drawstring. A flash of sorcery met his touch. Staggered by blinding pain, the prince recoiled.

Enemy hands caught and steadied him. ‘I warned you, didn’t I?’ said Arithon briskly. ‘Those knots are warded by sorcery.’

Riled by intense discomfort, the prince shoved to break free.

‘Stay still!’ Arithon’s hold tightened. ‘Movement will just prolong your misery.’

But dizzied, humiliated and agonized by losses far more cutting than the burns inflicted by the ward, Lysaer rejected sympathy. He stamped his heel full-force on Arithon’s bare instep. A gasped curse rewarded him. The offending hands retreated.

Lysaer crouched, cradling his arm while the needling pains subsided. Envy galled him for the arcane knowledge he had been denied as his enemy loosened the knots with impunity. The sack contained provisions. Acutely conscious of the oven-dry air against his skin, the prince counted five bundles of food and four water flasks. Lastly, Arithon withdrew a beautifully-crafted longsword. Sunlight caught in the depths of an emerald pommel, flicking green highlights over features arrested in a moment of unguarded grief.

Resentfully, Lysaer interrupted. ‘Let me take my share of the rations now. Then our chances stand equal.’

Arithon’s expression hardened as he looked up. ‘Do they?’ His glance drifted over his half-brother’s court clothing, embroidered velvets and fine lawn cuffs sadly marred with grit and sweat. ‘What do you know of hardship?’

The prince straightened, furious in his own self-defence. ‘What right have you to rule my fate?’

‘No right.’ Arithon tossed the inventoried supplies back into the sack and lifted his sword. ‘But I once survived the effects of heat and thirst on a ship’s company when the water casks broke in a storm. The experience wasn’t very noble.’

‘I’d rather take my chances than live on an enemy’s sufferance.’ Despising the diabolical sincerity of this latest s’Ffalenn wile, Lysaer was bitter.

‘No, brother.’ With unhurried calm, Arithon slung the sack across his shoulders. He buckled on the sword which once had been his father’s. ‘You’ll have to trust me. Let this prove my good faith.’ He reversed the knife neatly and tossed it at the prince’s feet. The jewelled handle struck earth, pattering sand over gold-stitched boots.

Lysaer bent. He retrieved his weapon. Impelled by antagonism too powerful to deny, he straightened with a flick of his wrist and flung the blade back at his enemy.

Arithon dropped beneath the dagger’s glittering arc. He landed rolling, shed the cumbersome sack, and was halfway back to his feet again at the moment Lysaer crashed into him. Black hair whipped under the impact of the prince’s ringed fist.

Arithon retaliated with his knee and returned a breathless plea. ‘Desist. My word is good.’

Lysaer cursed and struck again. Blood ran, spattering droplets over the sand. His enemy’s sword hilt jabbed his ribs as he grappled. Harried in close quarters he snatched, but could not clear the weapon from the sheath. Hatred burned through him like lust as he gouged s’Ffalenn flesh with his fingers. Shortly, the Master of Shadow would trouble no man further, Lysaer vowed; he tightened his hold for the kill.

An explosion of movement flung him back. Knuckles cracked the prince’s jaw, followed by the chop of a hand in his groin. He doubled over, gasping, as Arithon wrested clear. Lysaer clawed for a counterhold. Met by fierce resistance and a grip he could not break, he felt the tendons of his wrist twist with unbearable force. He lashed with his boot, felt the blow connect. The Master’s grasp fell away.

Lysaer lunged to seize the sword. Arithon kicked loose sand, and a shower of grit stung the prince’s eyes. Blinded, shocked to hesitation by dirty tactics, Lysaer felt his enemy’s hands lock over both of his forearms. Then a terrific wrench threw him down. Before he could recover, a hail of blows tumbled him across the ground.

Through a dizzy haze of pain, Lysaer discovered that he lay on his back. Sweat dripped down his temples. Through a nasty, unspeakable interval, he could do nothing at all but lie back in misery and pant. He looked up at last, forced to squint against the light which jumped along the sword held poised above his heart.

Blood snaked streaks through the sand on Arithon’s cheek. His expression flat with anger, he said, ‘Get up. Try another move like that and I’ll truss you like a pig.’

‘Do it now,’ the prince said viciously. ‘I hate the air you breathe.’

The blade quivered. Lysaer waited, braced for death. But the sword only flickered and stilled in the air. Seconds passed, oppressive with heat and desert silence.

‘Get up,’ the Master repeated finally. ‘Move now, or by Ath, I’ll drive you to your feet with sorcery.’ He stepped back. Steel rang dissonant as a fallen harp as he rammed the sword into his scabbard. ‘I intend to see you out of this wasteland alive. After that, you need never set eyes on me again.’

Blue eyes met green with a flash of open antagonism. Then, with irritating abandon, Arithon laughed. ‘Proud as a prize bull. You are your father’s son, to the last insufferable detail.’ The Master’s mirth turned brittle. Soon afterward, the sand began to prickle, then unpleasantly to burn the prince’s prone body.

Accepting the risk that the sensation was born of illusion, Lysaer resisted the urge to rise. The air in his nostrils seared like a blast from a furnace, and his hair and clothing clung with sticky sweat. Wrung by the heat and the unaccustomed throes of raw pain, the prince shut his eyes. Arithon left him to retrieve the thrown dagger. He gathered the fisherman’s cloak which had muffled Lysaer through his passage of the Gate and stowed that along with the provisions. Then the Master walked back. He discovered the prince still supine on the sand and the last of his patience snapped.

Lysaer felt his mind clamped by remorseless force. Overcome by the brilliant, needle-point focus in the touch which pinned him, he lost his chance to resist. The blow which followed struck only his mind, but a scream of agony ripped from his throat.

‘Get up!’ Sweat ploughed furrows through the dirt on Arithon’s face. He attacked again without compunction. The prince knew pain that seared away reason; left nothing beyond an animal’s instinct to survive, he screamed again. Peal after peal of anguish curdled the desert silence before the punishment ended. Lysaer lay curled in the sand, shaking, gasping and angered beyond all forgiveness.

‘Get up.’

Balked to speechless frustration, Lysaer complied. But wedged like a knot in his heart was a vow to end the life of the sorcerer who had forced his inner will.

The half-brothers from Dascen Elur travelled east. Red as the embers of a blacksmith’s forge the sun swung overhead, heating sand to temperatures that seared exposed flesh. Arithon bound his naked feet with strips torn from his shirt and urged the prince on through hills which shimmered and swam in the still air. By midday the dunes near at hand shattered under a wavering screen of mirage. The Master tapped his gift and wove shadow to provide shade. Lysaer expressed no gratitude. Poisoned through by distrust, he alternated between silence and insults until the desert sapped his fresh energy.

Arithon drove on without comment. The prince grew to hate beyond reason the tireless step at his heel. In time, the Master’s assumption that he was his father’s son became only partially true; the rage which consumed Lysaer’s thoughts burned patient and cold as his mother’s.

The heat of day peaked and waned and the sun dipped like a demon’s lamp toward an empty horizon. Lysaer hiked through a haze of exhaustion, his mouth bitter with dust. The flinty chafe of grit in his boots made each step a separate burden. Yet Arithon permitted no rest until the desert lay darkened under a purple mantle of twilight. The prince sat at once on a wind-scoured rock and removed his boots. Blood throbbed painfully through heels scraped raw with blisters, but Lysaer preferred discomfort to the prospect of appealing to the mercy of his enemy. If he could not walk, the Master could damned well carry him.

‘Put your hands behind your back,’ Arithon said sharply.

Lysaer glanced up. The Master stood with his sword unsheathed in one hand and an opened waterflask in the other. His expression remained unreadable beneath clinging dust and dried blood. ‘You won’t like the outcome if I have to repeat myself.’

The prince complied slowly. Steel moved with a fitful gleam in the Master’s hand. Lysaer recoiled.

‘Stay still!’ Arithon’s command jarred like a blow. ‘I’m not planning to kill you.’

Angered enough to throttle the words in his enemy’s throat, Lysaer forced himself to wait while smoke-dark steel rose and rested like a thin line of ice against his neck.

Arithon raised the flask to Lysaer’s lips. ‘Take three swallows, no more.’

The prince considered refusing but the wet against his mouth aggravated his craving past bearing; reason argued that only the s’Ffalenn bastard would benefit from water refused out of pride. Lysaer drank. The liquid ran bitter across his tongue. Parched as he was, the sword made each swallow seem an act of animal greed. Although Arithon rationed himself equally, the prince found neither comfort nor forbearance in the fact.

Moved by the hatred in the eyes which tracked his smallest move, Arithon made his first unnecessary statement since morning. ‘The virtues of s’Ilessid have been justice and loyalty since time before memory. Reflect your father’s strengths, your Grace. Don’t cling to his faults.’

With a slice of his sword, the Master parted the twine which bound a wrapped package of food. His weapon moved again, dividing the contents into halves before his battered scabbard extinguished the dull gleam of the blade. Arithon looked askance, his face shadowed in failing light. ‘Show me a rational mind, Prince of Amroth. Then I’ll grant you the respect due your birthright.’

Lysaer hardened his heart against truce; s’Ffalenn guile had seduced s’Ilessid trust too often to admit any pardon. With nothing of royal birthright left beyond integrity, self-respect demanded he endure his plight without shaming the family honour. Lysaer accepted cheese and journey-biscuit from Arithon’s hand in silence, his mind bent on thoughts of revenge in the moment his enemy chose to sleep.

But the Master’s intentions included no rest. The moment their meagre meal was finished, he ordered the prince to his feet.

Lysaer wasted no resentment over what he could not immediately hope to change. Driven outside impulsive passion, he well understood that opportunity would happen soonest if Arithon could be lulled to relax his guard. With feigned resignation the prince reached for his boots only to find his way blocked by a fence of drawn steel.

Sword in hand, Arithon spoke. ‘Leave the boots. They’ll make your feet worse. Blame your vanity for the loss. You should have spoken before you got blistered.’

Lysaer bit back his impulse to retort and stood up. Arithon seemed edgy as a fox boxed in a wolf’s den; perhaps his sorcerer’s self-discipline was finally wearing thin. Sapping heat and exertion would exact cruel toll on the heels of a brutal confinement. Possibly Arithon was weak and unsure of himself, Lysaer realized. The thought roused a predator’s inward smile. The roles of hunter and hunted might soon be reversed. His enemy had been foolish to keep him alive.

At nightfall, the sky above the Red Desert became a thief’s hoard of diamonds strewn across black velvet; but like a beauty bewitched, such magnificence proved short-lived. The mild breeze of twilight sharpened after dusk, swelling into gusts which ripped the dry crests of the dunes. Chased sand hissed into herringbone patterns and the alien constellations smouldered through haloes of airborne dust.

Lysaer and Arithon walked half-bent with their faces swathed in rags. Wind-whipped particles drove through gaps at sleeve and collar, stinging bare flesh to rawness. Isolated by hatred and exhaustion, Lysaer endured with his mouth clamped against curses. His eyes wept gritty tears. At every hour his misery grew, until the shriek of sand and wind seemed the only sound he had ever known. Memories of court life in Amroth receded, lost and distant and insubstantial as the movements of ghosts. The sweet beauty of a lady left at South Isle seemed a pleasure invented by delirium as reality was defined and limited by the agony of each single step.

No thought remained for emotion. The enemy at Lysaer’s side seemed to be a form without meaning, a shadowy figure in windblown rags who walked half-obscured by drifts of sand. Whether Arithon was responsible for cause or cure of the present ordeal no longer mattered. Suffering stripped Lysaer of the capacity to care. Survival forced him to set one sore foot ahead of the other, hour after weary hour. Finally, when the ache of muscle and bone became too much to support, the prince collapsed to his knees.

Arithon stopped. He made no move to draw his sword, but stood with his shoulders hunched against the wind and waited.

The sand blew more densely at ground level. Abrasive as sharpened needles, stony particles scoured flesh until sensitized nerves rebelled in pain. Lysaer stumbled back to his feet. If his first steps were steadied by the hands of an enemy, he had no strength left to protest.

Daybreak veiled the stars in grey and the winds stilled. The dust settled gradually and the horizon spread a bleak silhouette against an orange sunrise. Arithon at last paused for rest. Oblivious to hunger and thirst, Lysaer dropped prone in the chilly purple shadow of a dune. He slept almost instantly, and did not stir until long after daylight, when mirage shimmered and danced across the trackless inferno of sand.

Silence pressed like a weight upon the breezeless air. Lysaer opened swollen eyelids and found Arithon had propped the hem of the fisherman’s cloak with rocks, then enlarged the patch of shade with his inborn mastery of shadow. The fact that his makeshift shelter also protected his half-brother won him no gratitude. Though Lysaer suffered dreadful thirst, and his muscles ached as if mauled by an armourer’s mallet, he had recovered equilibrium enough to hate.

The subject of his passion sat crosslegged with a naked sword propped across his knees. Hair, clothing and skin were monochromatic with dust. Veiled beneath crusted lashes, green eyes flicked open as Lysaer moved. Arithon regarded his half-brother, uncannily alert for a man who had spent the night on his feet.

‘You never slept,’ the prince accused. He sat up. Dry sand slithered from his hair and trickled down the damp collar of his tunic. ‘Do you subsist on sorcery, or plain bloody-minded mistrust?’

A faint smile cracked Arithon’s lips. He caught the waterflask by his elbow with scabbed fingers and offered refreshment to the prince. ‘Three swallows, your Grace.’ Only his voice missed his customary smoothness. ‘Last night was the first of many to come. Accept that, and I’ll answer.’

Lysaer refused the challenge. The time would come when even Rauven’s advantages must yield before bodily weakness. Conserving his strength for that moment, the prince accepted his ration of water. Under the watchful gaze of his enemy, he settled and slept once again.

The three days which followed passed without variation, their dwindling supplies the only tangible measure of time. The half-brothers spent nights on the move, fighting sand-laden winds which permitted no rest. Dawn found them sharing enmity beneath the stifling wool of the fisherman’s cloak. The air smelled unrelentingly like baked flint, and the landscape showed no change until the fourth morning, when the hump of a dormant volcano notched the horizon to the east.

Lysaer gave the landmark scant notice. Hardship had taught him to hoard his resources. His hatred of Arithon s’Ffalenn assumed the stillness of a constrictor’s coils. Walking, eating and dreaming within a limbo of limitless patience, the prince marked the progressive signs of his enemy’s fatigue.

Arithon had been thin before exile. Now, thirst and privation pressed his bones sharply against blistered skin. His pulse beat visibly through the veins at neck and temple, and weariness stilled his quick hands. The abuse of sun and wind gouged creases around reddened, sunken eyes. Ragged and gaunt himself, Lysaer observed that the sorcerer’s discipline which fuelled Arithon’s uncanny alertness was burning him out from within. His vigilance could not last forever. Yet waking time and again to the fevered intensity of his enemy’s eyes, the prince became obsessed with murder. Rauven and Karthan between them had created an inhuman combination of sorcery and malice best delivered to the Fatemaster’s judgement.

On the fifth day since exile, Lysaer roused to the cruel blaze of noon. The leg and one arm which lay outside the shade of the cloak stung, angry scarlet with burn. Lysaer licked split lips. For once, Arithon had failed to enlarge the cloth’s inadequate shelter with shadow. Paired with discomfort, the prince knew a thrill of anticipation as he withdrew his scorched limbs from the sun. A suspicious glance showed the bastard’s hands lying curled and slack on the sword hilt: finally, fatally, Arithon had succumbed to exhaustion.

Lysaer rose with predatory quiet, his eyes fixed on his enemy. Arithon failed to stir. The prince stood and savoured a moment of wild exultation. Nothing would prevent his satisfaction this time. With the restraint the Master himself had taught him, Lysaer bent and laid a stealthy hand on the sword. His touch went unresisted. Arithon slept, oblivious to all sensation. Neither did he waken as Lysaer snatched the weapon from his lap.

Desert silence broke before the prince’s cracked laugh. ‘Bastard!’ Steel glanced, bright as flame as he lifted the sword. Arithon did not rouse. Lysaer lashed out with his foot. Hated flesh yielded beneath the blow: the Master toppled into a graceless sprawl upon the sand. His head lolled back. Exposed like a sacrifice, the cords of his neck invited a swift, clean end.

Irony froze Lysaer’s arm mid-swing. Instead of a mercy-stroke, the sight of his enemy’s total helplessness touched off an irrational burst of temper. Lysaer’s thrust rent the fisherman’s cloak from collar to hem. Sunlight stabbed down, struck the s’Ffalenn profile like a coin face. The prince smiled in quivering triumph. Almost, he had acted without the satisfaction of seeing his enemy suffer before the end.

‘Tired, bastard?’ Lysaer shoved the loose-limbed body onto its back. He shook one shoulder roughly, felt sinews exposed like taut wires by deprivation. Even after the abuses of Amroth’s dungeon, Arithon had been scrupulously fair in dividing the rations. Lysaer found the reminder maddening. He switched to the flat of his sword.

Steel cracked across Arithon’s chest. A thin line of red seeped through parted cloth, and the Master stirred. One hand closed in the dust. Before his enemy could rise, Lysaer kicked him in the ribs. Bone snapped audibly above a gasp of expelled breath. Arithon jerked. Driven by mindless reflex, he rolled into the iron-white glare of noon.

Lysaer followed, intent upon his victim. Arithon’s eyes opened, conscious at last. His arrogant mouth stretched with agony, and sweat glistened on features at last stripped of duplicity.

The prince gloated at his brutal, overwhelming victory. ‘Would you sleep again, bastard?’ He watched as Arithon doubled, choking and starved for breath. ‘Well?’ Lysaer placed the swordpoint against his enemy’s racked throat.

Gasping like a stranded fish, Arithon squeezed his eyes shut. The steel teased a trickle of scarlet from his skin as he gathered scattered reserves and forced speech. ‘I had hoped for a better end between us.’

Lysaer exerted pressure on the sword and watched the stain widen on Arithon’s collar. ‘Bastard, you’re going to die, but not as the martyred victim you’d have me think. Sithaer will claim you as a sorcerer who stayed awake one day too many, plotting vengeance over a bare sword.’

‘I had another reason.’ Arithon grimaced and subdued a shuddering cough. ‘If I failed to inspire your trust, I could at least depend upon my own. I wanted no killing.’

The next spasm broke through his control. Deaf to his brother’s laughter, Arithon buried his face in his hands. The seizure left him bloodied to the wrists, yet he summoned breath and spoke again. ‘Restrain yourself and listen. According to Rauven’s records the ancestors who founded our royal lines came to Dascen Elur through the Worldsend Gate.’

‘History doesn’t interest me.’ Lysaer leaned on the sword. ‘Make your peace with Ath, bastard, while you still have time for prayer.’

Arithon ignored the bite of steel at his throat. ‘Four princes entered this wasteland by another gate, one the records claim may be active still. Look east for a ruined city…Mearth. Beyond lies the gate. Beware of Mearth. The records mention a curse…overwhelmed the inhabitants. Something evil may remain…‘ Arithon’s words unravelled into a bubbling cough. Blood darkened the sand beneath his cheek. His forearm pressed hard to his side, he resumed at a dogged whisper. ‘You’ve a chance at life. Don’t waste it.’

Though armoured to resist any plea for the life under his sword, the prince prickled with sudden chills: what if, all along, he had misjudged? What if, unlike every s’Ffalenn before him, this bastard’s intentions were genuine? Lysaer’s hand hesitated on the sword while his thoughts sank and tangled in a morass of unwanted complications. One question begged outright for answer. Why had Arithon not knifed him straightaway as he emerged, drugged and helpless from the Gate?

‘You used sorcery against me,’ Lysaer accused, and started at the sound of his own voice. The aftershock of fury left him dizzied, ill, and he had not intended to speak aloud.

The Master’s features crumpled with the remorse of a man pressured beyond pride. Lysaer averted his face. But Arithon’s answer pursued and pierced his heart.

‘Would anything else have stiffened your will enough to endure that first night of hardship? You gave me nothing to work with but hatred.’

The statement held brutal truth. Lysaer lightened his pressure on the sword. ‘Why risk yourself to spare me? I despise you beyond life.’

The prince waited for answer. Smoke-dark steel shimmered in his hand, distorted like smelter’s scrap through the heat waves. If another of Arithon’s whims prompted the silence, he would die for his insolence. Nettled, Lysaer bent, only to find his victim unconscious. Trapped in a maze of tortuous complexity, the prince studied the sword. Let the blade fall, and s’Ffalenn wiles would bait him no further. Yet the weapon itself balked an execution’s simplicity; exquisitely balanced, the tempered edges designed to end life instead offered testimony on Arithon’s behalf.

The armourers of Dascen Elur had never forged the sword’s equal, though many tried. Legend claimed the blade carried by the s’Ffalenn heirs had been brought from another world. Confronted by perfection, and by an inhuman harmony of function and design, for the first time Lysaer admitted the possibility the ancestors of s’Ffalenn and s’Ilessid might have originated beyond Worldsend. Arithon might have told the truth.

He might equally have lied. Lysaer could never forget the Master’s performance before Amroth’s council, his own life the gambit for whatever deeper purpose he had inveigled to arrange. The same tactic might be used again; yet logic faltered, gutted by uncertainty. Torn between hatred of s’Ffalenn and distrust of his own motives, Lysaer realized that Arithon’s actions would never be fathomed through guesswork. Honour did not act on ambiguity. Piqued by a flat flare of anger, he flung the sword away.

Steel flashed in a spinning arc and impaled itself with a thump in the fisherman’s cloak. Lysaer glowered down at the limp form of his half-brother. ‘Let the desert be your judge,’ he said harshly. Aroused by the blistering fall of sunlight on his head, he left to collect half of the supplies.

Yet beneath the ruined cloak, irony waited with one final blow: the sword had sliced through the last of the waterflasks. Sand had swiftly absorbed the contents. Barely a damp spot remained. Lysaer struck earth with his knuckles. Horror knotted his belly, and Arithon’s words returned to mock him: ‘What do you know of hardship?’ And, more recently, ‘You’ve a chance at life. Don’t waste it…’ The sword pointed like a finger of accusation. Lysaer blocked the sight with his hands, but his mind betrayed and countered with the vision of a half-brother lying sprawled in pitiless sunlight, the marks of injustice on his throat.

Guilt drove Lysaer to his feet. Shadow mimed his steps like a drunk as he fled toward empty hills, and tears of sweat streaked his face. The sun scourged his body and his vision blurred in shimmering vistas of mirage.

‘The wasteland will avenge you, bastard,’ said Lysaer, unaware the heat had driven him at last to delirium.

Arithon woke to the silence of empty desert. Blood pooled in his mouth, and the effort of each breath roused a tearing stab of agony in his chest. A short distance away the heaped folds of the cloak covered the remains of the camp he had shared with his half-brother. Lysaer had gone.

Arithon closed his eyes. Relief settled over his weary, pain-racked mind. Taxed to the edge of strength, he knew he could not walk. His sorcerer’s awareness revealed one lung collapsed and drowned in fluid. But at least in his misery he no longer bore the burden of responsibility for his half-brother’s life. Lysaer would survive to find the second gate; there was one small victory amid a host of failures.

The Master swallowed, felt the unpleasant tug of the scab which crusted his throat. He held no resentment at the end. Ath only knew how close he came to butchering a kinsman’s flesh with the same blade that symbolized his sworn oath of peace. Cautiously, Arithon rolled onto his stomach. Movement roused a flame of torment as broken bones sawed into flesh. His breath bubbled through clotted passages, threatened by a fresh rush of bleeding. The Master felt his consciousness waver and dim. A violent cough broke from his chest and awareness reeled before an onslaught of fragmenting pain.

Slowly, patiently, Arithon recovered control. Before long, the Wheel would turn, bringing an end to all suffering. Yet he did not intend that fate should overtake him in the open. Death would not claim him without the grace of a final struggle. Backing his resolve with a sorcerer’s self-will, Arithon dragged himself across the sand toward the fisherman’s cloak.

Blood ran freely from nose and mouth by the time he arrived at his goal. He reached out with blistered fingers, caught the edge of the wool and pulled to cover his sunburned limbs. As the cloak slid aside, his eyes caught on a smoky ribbon of steel. Cloth slipped from nerveless fingers; Arithon saw his own sword cast point first through the slashed leather of the water flask.

A gasp ripped through the fluid in his chest. Angry tears dashed the sword’s brilliance to fragments as he faced the ugly conclusion that Lysaer had rejected survival. Why? The Master rested his cheek on dusty sand. Had guilt induced such an act? He would probably never know.

But the result rendered futile everything he had ever done. Arithon rebelled against the finality of defeat. Tormented by memory of the lyranthe abandoned at Rauven, he could not escape the picture of fourteen silver-wound strings all tarnished and cobwebbed with disuse. His hopes had gone silent as his music. There stood the true measure of his worth, wasted now, for failure and death under an alien sun.

Arithon closed his eyes, shutting out the desert’s raw light. His control slipped. Images ran wild in his mind, vivid, direct and mercilessly accusing. The high mage appeared first. Statue straight in his hooded robe of judgement, the patriarch of Rauven held Avar’s sword on the palms of his upraised hands. The blade dripped red.

‘The blood is my own,’ Arithon replied, his voice a pleading echo in the halls of his delirium.

The high mage said nothing. His cowl framed an expression sad with reproach as he glanced downward. At his feet lay a corpse clad in the tattered blue and gold of Amroth.

Arithon cried out in anguished protest. ‘I didn’t kill him!’

‘You failed to save him.’ Grave and implacably damning, the vision altered. The face of the high mage flowed and reshaped into the features of Dharkaron, Ath’s avenging angel, backed by a war-littered ship’s deck. By his boots sprawled another corpse, this one a father, shot down by an arrow and licked in a rising rush of flame.

As the sword in the Avenger’s grip darkened and lengthened into the ebony-shafted Spear of Destiny, Arithon cried out again. ‘Ath show me mercy! How could I twist the deep mysteries? Was I wrong not to fabricate wholesale murder for the sake of just one life?’

Gauntleted hands levelled the spear-point at Arithon’s breast; and now the surrounding ocean teemed and sparkled with Amroth’s fleet of warships. These had been spared the coils of grand conjury, to be indirectly dazed blind through use of woven shadow, their rush to attack turned and tricked by warped acoustics to ram and set fire to each other until seven of their number lay destroyed.

Dharkaron pronounced in subdued sorrow, ‘You have been judged guilty.’

‘No!’ Arithon struggled. But hard hands caught his shoulders and shook him. His chest exploded with agony. A whistling scream escaped his throat, blocked by a gritty palm.

‘Damn you to Sithaer, hold still!’

Arithon opened glazed eyes and beheld the face of his s’Ilessid half-brother. Blood smeared the hand which released his lips. Shocked back to reason, the Master dragged breath into ruined lungs and whispered, ‘Stalemate.’ Pain dragged at his words. ‘Did Ath’s grace, or pity bring you back?’

‘Neither.’ With clinical efficiency, Lysaer began to work the fisherman’s cloak into a sling. ‘There had better be a gate.’

Arithon stared up into eyes of cold blue. ‘Leave me. I didn’t ask the attentions of your conscience.’

Lysaer ignored the plea. ‘I’ve found water.’ He pulled the sword from the ruined flask and restored it to the scabbard at Arithon’s belt. ‘Your life is your own affair, but I refuse responsibility for your death.’

Arithon cursed faintly. The prince knotted the corners of the cloak, rose and set off, dragging his half-brother northward over the sand. Mercifully, the Master lost consciousness at once.

Shaded by twisted limbs, the well lay like a jewel within a grove of ancient trees. The first time Lysaer had stumbled across the site by accident. Anxious to return with his burden before the night winds scattered the sands and obscured his trail he hurried, half-sliding down the loose faces of the dunes then straining to top the crests ahead. His breath came in gasps. Dry air stung the membranes of his throat. At last, aching and tired, the prince tugged the Master into the shadow of the trees and silence.

Lysaer knew the grove was the work of a sorcerer. Untouched by desert breezes, the grass which grew between the bent knuckles of the tree roots never rustled; the foliage overhead hung waxy and still. Here, quiet reigned, bound by laws which made the dunes beyond seem eerily transient by comparison. Earlier, need had stilled the prince’s mistrust of enchantment. Now Arithon’s condition would wait for no doubt. The well’s healing properties might restore him.

At the end of his strength when he drank, Lysaer had discovered that a single swallow from the marble fountain instantly banished the fatigue, thirst and bodily suffering engendered by five days of desert exposure. When the midday heat had subsided, and the thick quiver of mirage receded to reveal the profile of a ruined tower on the horizon, the prince beheld proof that Mearth existed. Though from the first the Master’s protection had been unwanted and resented, s’Ilessid justice would not permit Lysaer to abandon him to die.

The prince knelt and turned back the cloak. A congested whisper of air established that Arithon still breathed. His skin was dry and chill to the touch, his body frighteningly still. Blood flowed in scalding drops from his nose and mouth as Lysaer propped his emaciated shoulders against the ivy-clad marble of the well.

Silver and still as polished metal, water filled the basin to the edge of a gilt-trimmed rim. Lysaer cupped his hands, slivering the surface of the pool with ripples. He lifted his hand. A droplet splashed the Master’s dusty cheek; then water streamed from the prince’s fingers and trickled between parted lips.

Arithon aroused instantly. His muscles tensed like bowstrings under Lysaer’s arm and his eyes opened, dark and hard as tourmaline. He gasped. A paroxysm shook his frame. Deaf to the prince’s cry of alarm, he twisted aside and laced his slender, musician’s fingers over his face.

Lysaer caught his half-brother’s shoulder. ‘Arithon!’

The Master’s shielding hands fell away. He straightened, his face gone deathly pale. Without pause to acknowledge his half-brother’s distress, he rolled over and stared at the well. Settled and still, the water within shone unnatural as mirror-glass between the notched foliage of the ivy.

Arithon drew breath and the congestion in his lungs vanished as if he had never known injury. ‘There is sorcery here more powerful than the Gate.’

Lysaer withdrew his touch as if burned. ‘It healed you, didn’t it?’

The Master looked up in wry exasperation. ‘If that were all, I’d be grateful. But something else happened. A change more profound than surface healing.’

Arithon rose. Brisk with concentration, he studied every tree in the grove, then moved on to the well in the centre. The prince watched, alarmed by his thoroughness, as Arithon rustled through the ivy which clung to the rim of the basin. His search ended with a barely audible blasphemy.

Lysaer glimpsed an inscription laid bare beneath ancient tendrils of vine; but the characters were carved in the old tongue, maddeningly incomprehensible to a man with no schooling in magecraft. In a conscious effort to keep his manners, Lysaer curbed his frustration. ‘What does it say?’

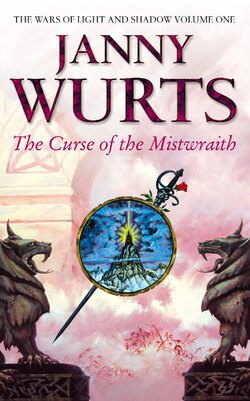

Arithon looked up. Bemused, he said, ‘If these words spell truth, Daelion Fatemaster’s going to get a fair headache over the records before the Wheel turns on us. We appear to have been granted a five hundred year lifespan by a sorcerer named Davien.’ The Master paused, swore in earnest, and ruefully sat on the grass. ‘Brother, I don’t know whether to thank you for life, or curse you for the death I’ve been denied.’

Lysaer said nothing. Taught a hard lesson in tolerance after five days in the desert, he regarded his mother’s bastard without hatred and found he had little inclination to examine the fountain’s gift. With Dascen Elur and his heirship and family in Amroth all lost to him, the prospect of five centuries of lengthened life stretched ahead like a joyless burden.