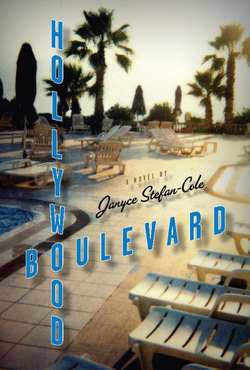

Читать книгу Hollywood Boulevard - Janyce Stefan-Cole - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

L e a v i n g J o e

Iused to think about quitting all the time. Then I quit, and now I still think about it. Maybe the dream slipped away, or got sullied into something no longer recognizable, or came at too high a price— as in be careful what you wish for. So I float between a sleeping dream and real life. At the moment I'm holed up at the hotel swimming pool, a terraced affair set below a pricey Japanese restaurant, with narrow gardens guests can visit via little golden keys that open short red gates to various paths. It's off- season, the unheated pool is glacial; leaves fall in, float a while, and sink. A Shinto gate sits importantly on the pool's south side, like offspring of the restaurant above. The landscaping is uneven: artificial waterfalls, a miniature pomegranate tree, the Shinto gate aligned with a chain- link fence facing nondescript Hollywood back streets below; calm and common all at once.

The maid cleaning my room is the reason I am lying low, wrapped in layers against the early- spring chill. What does the staff think of me in my suite— with kitchen— so much of the time? The awkwardness of having to get out of the maid's way so my mess can be cleaned, though I like not having to do it myself and have mostly not had to. Her arrival threatens my days. Today the interruption came near noon; tomorrow it could be three p.m. or ten thirty a.m. Maid or no maid, I prefer my mornings. A day that ends badly may have begun with sunlit, wide- awake eyes. It doesn't take much to tip the scales; my mornings do not inform my nights, they never have.

Too persistently the question arises just what the maid is interrupting. The answer is always a big nothing. I was an actor until I quit, walked away, some said with my best work in front of me, but that sort of talk comes cheap; quitting does not. Can the maid, Zaneda— I think that's what she said her name is— imagine my life as I can so easily imagine hers? What does she think I am doing at the pool, noticing the haphazard landscaping while the sweet Chicana makes my very tossed bed? Does she wonder that there are no signs of sex on the sheets? Her prettiness is homey, eyes behind wire glasses gentle. She treats me as if I am special.

"El Señor is a director of movies, no?" she asked when I first arrived. She meant my husband, Andre Lucerne.

" Señor is a director of movies, sí," I replied, cutting the conversation short. El Señor insisted I come, which explains in a nutshell my presence at the Hotel Muse. My having agreed, my being back in Hollywood while he shoots his film, could spell trouble, like a recovering junkie camped out in the poppy fields.

He said he needed me by his side. That's not how Andre expresses himself. He expresses himself through his work, so I was surprised by his words and, I admit, a little suspicious, and I don't know why I agreed to come.

I'm not sure how much English Zaneda understands. I try to speak to her in Spanish. I did learn that she has four children, aged sixteen to three. She works long, hard hours, traveling who knows how far to get to the hotel, by car or bus or metro, to support those many kids. Yet her smile is uncompromised by exploitation. I think she said the other day that she'd seen me in a movie once. Possibly I misunderstood. It hasn't been that long since I quit, but Hollywood develops amnesia faster than a corpse forgets to breathe. I don't have to escape my room and Zaneda's enduring reality against my— what?— ethereal existence, but if explanations begin to be required, of how I spend my days and why I stopped acting, then I have no choice but to flee. Imagined conversations can be worse than actual ones.

I shifted my chaise three times just now. The sun was warm, out of the breeze. I looked up, hearing voices above me in the outdoor grill area that has been vacant each time I've come here before. I closed my eyes to wish the intruders away.

I dozed a few minutes, and now the voices have gone. It was probably safe to go back to my rooms, but I began rearranging the deck chairs instead. I walked the perimeter and found four wasted beer bottles tossed in a corner next to a blooming bird- of- paradise. Three days ago I walked the Japanese garden paths for the first time. Past stunted sculpted trees and little waterfalls and pools with timid goldfish that skittered away at my approach. Directly below the restaurant is a small pavilion with steep steps leading to it and two red benches under a peaked roof, a spot for viewing sunsets. Precisely below, a matter of inches from the pavilion, I noticed a bubblegum- blue used condom. I examined the red bench where the event had probably taken place. Maybe the couple had been drunk or in a hurry, the condom tossed in the dark. The next day it was still there. The find was solid gold, treasure a secret observer lives for— I've become a kind of hotel spy in my endless spare time. The restaurant has a reputation, so I was surprised to see the prophylactic lying there, but it's off- season and we are in a recession; cleanups might not be what they have been. Still.

I kicked the beer bottles next to the chain- link fence. I ought to have resisted the desire to arrange the pool deck but didn't. Having to arrange, needing to, possibly reflects something wrong with me. But I'm not interested; what good would it do if I learned I was a compul sive this or that, a so- and- such unable to reveal myself except through gestures like rearranging furniture, an utterly failed communicator— for an actor? I enjoy few things better than creating order out of chaos, yet my life is a study in disorder. Lurking is the awareness, faint and intermittent, occasionally urgent, that something is wrong and does need fixing. Or maybe the pool area looking a lot better now is explanation enough.

Husband number one said I only played at house. This was around the time I signed with Harry and Hollywood. That would be Harry Machin, Big Time Agent and proprietor of the very exclusive Machin Talent. Apparently with issues of his own— I mean the ex, a writer, he once hid out in a broom closet. I'd taken him to a party, not an A- list deal but sufficiently who's who. I didn't notice him missing until the hostess found him among the cleaning products and whispered in my ear to ask what was wrong with my guy. Back then I thought we would be a comfort to each other in social situations. I thought that's what couples did. Social outings are knotty anyway, on a guy's arm or flying solo. At the time of the closet incident I was better at taking cues and holding up my end, though I'd wilt at the smallest off- key passage: a casually unkind word, the bon mot landing flat. Still, I had a solid sense of what I wanted to be when I grew up, and nothing was going to stop me; I'd run over anyone who tried. I'm not saying I don't savvy the parley, flirting just enough to raise an eyebrow, playing the provocateur until my energy saps and I collapse like a diseased lung, sagging under the weight of human contact. Which, considering the assumed largeness of ego expected in my former profession, and the supposed need of an audience, makes me a candidate for problems from the start.

At a recent party here in Hollywood— no, Silver Lake, to be precise— where I knew enough people well enough to indulge in conversational back- and- forth, I left the crowd to play with the family's five- year- old, Ella. She proudly exhibited her many fairy dolls. All showy dresses, translucent wings, and long luscious hair, blond and thick like hers. After oohing and aahing appropriately, I began checking for underwear, lifting gossamer gowns, cotton pinafores, and tulip minis. "Let's see if she's wearing underpants," I said, peering at one doll's lower parts. Soon the dear little girl was checking too. "Underpants!" she'd say. "Underpants," we'd say, examining each doll. "No underpants!" she gasped. "Let's see!" I said, pulling the delinquent figurine from her small hand. Seeing the naked, rubbery flesh- colored blank where genitals ought to be, it occurred to me that I'd taught this lovely child something her parents might not appreciate. What was I thinking? Children are so unself- consciously sexual as it is, and she was just at that Freudian cusp, five, the postphallic stage, on the verge of the superego. I've perused a few pages of Freud, and he's a pessimist, if you ask me, and all wrong about penis envy. My grandmother used to say men start wars to match the heroics of women producing babies. Who knows, maybe they have the envy. That's a thorny topic, though, starting with Adam trying to shift blame onto a wily snake, quite possibly the beginning of blaming the victim, and certainly the genesis of men getting all the good lines in movies while the actresses get the great clothes. And I'm not certain there really is a victim, though I read somewhere that, according to Victorian mores, a "lady lies still" during the sex act. And what, studies the ceiling? I know it's a mixed- up ball of wax if the lady is taking it passively on her tummy or handing it out on top. Sex could be simple, lovely fun, but somehow there are always complications.

Anyhow, another guest (at the party), who happens to be a good- looking dwarf, poked his head through the doorway. "Are you hiding out in here?" he asked.

"Hiding out, yes," I said softly (trying, I think, for an effect. Why? Because he was born condensed?), realizing a split second later that he meant the little girl. He abruptly left.

There is some truth to what my ex said about how I play house. I spent time and some money nesting in the current suite. Which means I think I'll stay, though I threaten Andre from day to day to clear out back to our loft in New York. I've lived countless days and months in hotels, and I've learned it's important to claim the place, leave my mark like a dog peeing on a pole. But my ex implied it's all pretense, that things are not so clean under appealing surfaces. Dirt's not the point, I once tried to explain, but the way a space feels: harmonious or not, high or low contrast, and lighting— lighting is of utmost importance. He scoffed, "Spoken like a true actress." He told me I see things as others would, like a performance. As if light and color don't have real effect. "What's wrong with considering the effect?" I asked, apparently missing the point.

"Life," he said, "my pretty- pretty, is not an effect." (You know, I knew that.)

"Then you can be my resident reality check," I said, trying to disarm a potential fight. He frowned— set to object— but I jumped in: "Actors require reality checks; didn't that come with my instruc tions?"

Harry— this was back then— told me to cut "the hubby" loose. "Get him off the nipple; he's nothing. You're a great actress, the next Kate Hepburn."

"Harry, you know I can't stand Hepburn."

"I meant you're classy, not flimflam in a costume. Never a cheap shot from Ardennes Thrush."

That sounded like a line he might have used before. I didn't have a comeback, so I just sat there, opposite Harry at his very wide, bleached- birch desk, so wide it seemed like the deck of a small ship.

"I see what he is," Harry said to my silence. "That— what's his name again?"

"Joe?"

"Joe. Perfect. Joe Schmo. He's a moper. He'll never let you succeed. He'll tear down anything you do. Trust me on this. Guys like that prey on a woman's weakness."

I thought, isn't that what producers and the other money men do? There was an iota of truth to Harry's words, though; Joe did seem at times to debunk my growing success. What surprised me was Harry picking up on that part of Joe after at most two very brief meetings. I wondered how a deal- making manipulator like Harry Machin could have such insights. Maybe it was because Harry truly enjoyed what he did, was in it up to his elbows with all his heart.

"He doesn't have an agent, does he?" Harry added, watching me from under those heavy eyelids of his.

He didn't. I kept quiet again. Harry's phone rang. He said, "Okay," into the receiver, which meant he'd take the call. Which meant it was someone important because when Harry called you into the office he meant business and had his calls held. Harry was always telling me what to do and I was always trying to sort out for myself what I should do. Which is not to imply I knew back then what was best for me, but when I didn't know, I had my ready fall back position, which was to hold out. I was named after the Ardennes Forest, where what is called the Battle of the Bulge took place in the bitter winter of 1944. My father was a boy of twenty and he made it out alive when something on the order of 81,000 GIs were wounded, died or went missing in the last merciless thrust of the Nazis. I wasn't born then, not even close. My mother wanted to name me Autumn, after her favorite season, when she and my dad married. He was a good deal older than his second wife, just as my half- brother and -sister were to me. My mother said it wasn't a good idea to name a child, a girl no less, after a World War II battle, but I'd had a rough go of it and wasn't expected to live because of a problem in my tiny heart, a valve that they were able to reroute or something, and my dad told her I was a fighter and a survivor, like him. Maybe he figured he might not be around for me as long as most dads and wanted me to remember the young soldier who'd made it through the Ardennes Offensive. Anyhow, my mother agreed, and if I don't tell people the origin they think my name is exotically French or that I made it up as a stage name. I don't usually bother to explain.

It was probably just as well he wasn't around when I quit acting. How could I tell my dad it was the thought of quitting that kept me going? That the idea was a relief, like death, if you try to look into death's positive light, its silver lining. I don't mean to be morbid; in fact, I think it's morbid to want life to go on forever. There'd be no edge, just a soppy on and on. Maybe deep down inside everyone dreams of quitting, of being free of the task each of us supposedly has in life. I picked up that idea— about the task each of us has— from reading Sufiwisdom, the catch being, I suppose, finding the destined path. I sometimes wonder if Joe would have celebrated my quitting. We'd have made a normal life together; I'd have cooked dinner and been home to ask how his day had been. I once told Harry I gave my best performances on the days I was sure I would drop out. He wept the day I told him I was through; honest- to- goodness tears, nose honking, hanky and all.

"This is a crime against God," he said when he could finally speak.

His extreme reaction surprised me. "Against God, Harry?"

"Why? Tell me how your kind of talent quits, throws itself into the toilet and flushes. How?"

"It's not as if I was single- handedly making you rich," I said, trying for levity. I think I thought he'd get mad, yell, insult me, anything but that pained expression as he slowly shook his oversized head. He spent the next hour telling me what was wrong with my decision. He barked at his secretary to hold everything: "Everything, even if it's the president of the United States on the line!" I just remember being thirsty as he carried on. The longer he went on, the thirstier I got. This is where the Battle of The Ardennes comes in: I can hold out against just about anybody's verbal barrage to get me to change my mind. The more they try, the more I dig in. The truth is, I can black out the whole world, blacker than the blackest cave two miles into the bowels of the earth. I can go to a place so dark it's as if the world was never created. So Harry couldn't squeeze out of me why I quit, try as he did. He couldn't blame Joe either; it was too late for that. And by the way, Harry had nothing to do with Joe and me busting up. He did practically dance a jig on his desktop when he found out, but that was before I called it quits.

It took me a long time to shake Joe, considering the rough ride we'd had almost from day one. I'm not sure I ever did shake him. I've always been attracted to writers and this one was no slouch, though he could barely earn a dime on his work the whole while we were together. He had socialist ideas too, so that if I did bring in a nice check from time to time, a part in a pet- food commercial, say, that went national— with hefty residuals— it was right away suspect, like Chairman Mao or Lenin would get wind of Joe having had dealings with the capitalist devil.

Joe had a lot of anger. Not because the world had been unjust to him but because it's an unjust place. For me, the world's too big to be angry at all in a gulp. Joe scolded old friends too, if they betrayed the code. He would go on for days about the crime of getting a book published for a sum that had to be corrupt. What kind of whore game did he play to get that advance? Christ! But the lapsed friend was only a pawn of the society that had wrought him, a culture of which Joe disapproved and felt punished living in. Joe's basic premise was if people at the top would only wise up and take less, things could even out.

Happily, not even Joe could contemplate the distribution of wealth every day, and if he didn't bother too much about saving the world, he was just the guy I wanted. Basically, he lived simply, wanting most of all to read and write and think. The two of us, side by side reading in bed, Joe charming me with a passage of Yeats or Wordsworth pulled out of the air. Knowing when I was lost in my lines rehearsing for an off- off- Broadway play, a cold- water, firetrap stage. Showing up at late- night rehearsals, walking me home after midnight, streets solitary and slick, maybe one of those cat- sized rats running out from behind a trash can, Joe saying there were worse rats than them living in penthouse apartments. Giving me notes, really, really wanting me to soar; that was where I wanted my world to be.

He kept me guessing too, not a dull bone to him; there was always a new corner to turn with Joe. I never got all the way inside. Then again, Joe didn't think it was possible for an actor to get truly close. Or did he mean that about me only? All those emotions, he'd say, faking it with a part, how would anyone know if the tears at home weren't just more of the same?

Finally exasperated, I said, " Maybe they aren't ever an act."

"That only proves it, even you don't know," he shot back.

Worse than that was the time he said I was empty when no one was looking. It was only years later that the rejoinder came to me: How would you know? How could you possibly know, Joe? Was he knowing or only passing judgment? He'd get me all confused. Partly because I needed him to be right and partly because I needed him so much that I'd get muddled and couldn't think what to say, maybe couldn't think at all.

It was moving to L.A. that finally did the marriage in. Harry was after me to settle out west from the first big job he landed me: four scenes in a star- cast movie, thirty lines. My character— Laurel, early twenties— was not a hooker but available to wealthy men with fetishes like foot sucking or egg rolling. My first scene had me in a slinky summer dress: I walk into a darkened hotel room, balcony shutters closed to the tropical sea beyond, strips of sunlight piercing through the slats. A thug slips out of the shadows.

Thug: "What are you doing here?"

Laurel, frightened but keeping her cool: "I left my hat."

Thug: "Who let you in?"

Laurel: "I'm a friend of Abe's."

Thug, looking Laurel over like she's quick lunch: "Nobody's a friend of Abe's. Whaddaya, servicing his spanking needs?"

CUT!

It would be my one and only megamovie role. After that the studios made some overtures, smelled young blood in the water, but I wasn't interested. It wasn't as if Paramount was breaking down the door, but if Harry had his way I'd have cultivated myself, played along. Harry's line was that you have to wade through a little garbage to get to the high road you're meant to be on; that nothing good comes pure. Joe helped me steer clear of what he saw as Harry's hype. Some said Joe's steering might have ruined me. Anyhow, I got noticed in the medium- budget and indie- film worlds. Joe was okay with that. He'd ranted when I took the mega job, paragraphs' worth, and promised not to touch one penny of the filthy lucre I was paid, going so far as to set up a separate account for himself. He did live by his word.

I began flying back and forth between New York and Los Angeles. With the bigger parts I had to stay out for longer spells, and the parts were getting bigger. I made a few friends and stopped making so much fun of the too- friendly Angelinos. There's too much space is the problem, that's why they're so eager to connect. I once had a woman start a chat from underneath the next toilet stall. That was technically not in L.A. but at a stop for date shakes at Hadley's on the 10 Freeway, the San Bernardino route to Palm Springs, out past the wind farm that took my breath away every time I saw those thousand arms circling crazily over the arid earth. But people talk to strangers in elevators, other customers in a store, standing at a stop light, all friendly and open. I never got used to it.

I did get Los Angeles itself, a tactile place with big light and lots of texture where nature hasn't been conquered. Earthquakes lie in wait, full- blown desert only a hard drought away. Rub the surface of anyone who's been there long enough and you'll find a seeker. It doesn't much matter after what— L.A. is cult nirvana— some sort of god quest over the rainbow, born of that light and an underlying sense that all this gorgeousness can't last. The only thing people in New York City seek, my singer friend Dottie once let me know, is a way out. Dottie did her time in the Big Apple, but she was from Kansas and wide- open space was home to her and that translated into Los Angeles. In her case, her cabaret career faltered. We sort of reversed each other: I was always glad to get back to New York and Joe. I was never going to put down roots in that shallow western soil.

My time in Hollywood— especially my first serious movie— was more like a prolonged in- passing friendship. Mostly I was holding my emotional breath. Joe and me having phone sex, trying hard to keep it real over long distance. Harry giving me no peace, making threats, saying I was hurting my career by not making myself available to the machinery, that I wasn't hungry enough and was being passed over. He said if I wanted things to happen I had to get out there and get dirty.

"You're a Hollywood dame," he harangued. "Look at you, you blossom in the sunlight."

I'll never forget that conversation. It was winter, it was cold and wet. I was wrapping up a part, my ticket home already purchased. "It's been raining in L.A. for three days, Harry."

"Ardennes, Ardennes, Ardennes, when will you come to your senses?"

"I'm a New York– based actor. For the umpteenth time: I'll come out anytime a good part calls, but home is—"

He cut me off with a grunt and a half wave of his left hand, temporarily lifted off its perch on his belly. "Home! With Joe and the two cats, a dark, roach- infested apartment. Are the cats helpful there? Listen to me: What makes a rose more beautiful?" I lifted my hands to say, tell me. "Manure, that's what. Cow shit in the soil. See my point? You gotta taste it, Ardennes, you gotta sacrifice to it morning, noon, and night; you gotta want the prize, and you gotta make the journey to the prize."

What Harry didn't see was that, different as we were, Joe and I overlapped in crucial ways. He could pick up a false note in my work and excise it like a surgeon. And I loved those two cats, Molly and Corot, and our too- small West Side flat. The dark streets of New York were like the veins along my hands, avenues and boulevards in my blood. I held New York close in my heart. "Success at what price, Harry?"

He looked at me from below those heavy lids, scanning my interior, a stone Buddha, arms across his large front. "You think I talk of crass success? Dollar bills falling out of your brassiere, manse in the hills with the saline pool, ego billing on the marquee? You think I don't know you? Craft, Ardennes— A- R- T— is not going to settle for trysts and one- night stands, rendezvous in a bus station. A- R- T wants all of you! And all of you is all I want you to be."

It sounded so enlightened.

"Poetic, Harry," I said. I looked at my watch. "I gotta run, a night shoot today. I'm due on set at four." I stood up, reaching for my purse. I still didn't know why Harry had called me in that day. I was hoping for a month off, time with Joe.

He barely stirred, ever so slightly lifted that left hand again. "You got the part."

"What? You mean Separation and Rain? The lead ?"

Harry nodded sagely. "You start one hour before this part ends. No time to go home and feed the cats."

I whooped, I spun, I clapped my hands. I was young enough to whoop and spin. I was big- eyed, all goals, virgin territory; I was all the places I would never get to that I would strive for until the last breath was out of me. This was big, colossal, this would move the earth: a plum part I knew I was right for, that I wanted badly, that would give me the chance to really show what I knew I had untapped inside me. This was my shot to breathe life into a character half alive on paper; this was my Michelangelo: Adam reaching out to touch the hand of God. Okay, I was not about to be God to some Adam, but I would make that character live. I would! Wouldn't I? I flashed on a memory of Joe and me stretched out on a blanket on the rolling grass of the Sheep Meadow in Central Park. Joe poured wine into a thermos so we wouldn't be caught drinking out in the open. We had a baguette and cheese, and grapes, I think. We were having a what- if- one- of- us- makes- it conversation we had a lot in those days, and Joe said I wouldn't be able to take it anyway if I did make it big. He was tender about it. He knew how uncomfortable strange surroundings can make me, and that too many demands send me into a confused tailspin so I lose my bearings and need to run away. "I should have been a librarian," I told him that day. Joe said, "Nah, not with that face; none of the boys would get any homework done." I smiled at him from my toes up to my heart. "Your home is with me," he said. That was a good moment, the kind that can make up for so much, that ought to be the real essence of being alive but somehow never is.

"Harry, don't fool with me."

Harry's eyelids widened a fraction. "I never fool," he said with mild indignation.

"Then this is real!" I felt my breath catch. "The lead . . ." I sat down. This was a twenty- million- dollar budget with a solid script and a superior director. (I didn't know that day— and it was a few years off— that I would one day be married to Andre Lucerne, perhaps the most demanding director in Hollywood.) "You're sure? Andre Lucerne cast me?" I remember the doubts starting to creep in, that a mistake had been made, a mix- up in head shots or the audition tapes. I even suspected Harry might have bribed the producer, used blackmail, called in a life- and- death favor owed and I would be found out and dismissed as a fraud. I was working up to full- fledged panic when I heard Harry moving.

He lifted his cumbersome frame out of the plush leather desk chair and waddled to a small fridge you wouldn't know was there, tucked beneath some shelves in the well- appointed, screaming- success office. He leaned down heavily and pulled out a split of champagne, and from a nearby cabinet two flutes. "If you didn't have work tonight, we'd celebrate properly at Spago, on the Strip. Will this do for now?" He held up a bottle of Cristal. Spago was the place to be seen; the Cristal cost about what a New York City immigrant garment worker made in a week. He popped the cork and poured out wine and fizz.

I reached blindly for the glass Harry pushed toward me. I'd had my small victories; some— plenty of— actors would say I was in a good place even without this bit of luck, but I suddenly didn't know what to do, didn't know how to handle getting what I wanted. Harry was always saying luck had nothing to do with it, but that's not so; luck is either at work in a person's life or it's not. I sagged backward into the thick cushions of Harry's buffalo- hide sofa and put the flute down on the coffee table. Harry chuckled. I looked up; tears filled my eyes, ready to spill over. " Thank you, Harry," I whispered.

"Don't thank me. All I did was make a few calls, let the world know an angel had descended. You did the rest."

That snapped me back to my senses. I never knew if Harry bought his own lines or not. I jumped up, pointing to the phone on his desk. "I have to tell Joe!"

Harry snorted. "Go ahead, call that chump. You're halfway up the mountain; see if he can't find a way to drag you back down."

I smiled. "Don't ruin it, Harry," I said, reaching for the flute

with my right hand as I punched in the numbers with my left. I raised the glass to Harry and took the bubbly down in one swallow. I listened impatiently to Joe's ring tone but hung up when the leave- a- message voice came on. I didn't leave one. I canceled the call and saw what I'd just done register on Harry's face. I looked at him as I chewed on my lower lip.

"This is a game changer, Ardennes," Harry said. "Nothing will be the same after today." And nothing ever was.

So here I am in L.A., climbing a mountain of remembering, killing a day piled high with the past. I should give Proust another try. I walked idly up to the pavilion to check on the condom before heading back to my freshly cleaned rooms. Remembrance of Things Past— I never got through it. Joe did; all seven volumes in one year, ten pages a night. Joe, what's he up to now? I miss his ironclad discipline. I've read all his books, four so far. Remembrance of Joe . . . There it is! Dropped a foot farther down toward the parking lot, lying in the dirt; sunshine has baked the rubber hard, the semen into crisp mica crusts. Do the lovers remember their fallen condom; is it part of their meaningful past?

Where did I see that rosemary the other day, along one of the paths? I wanted to pick a few stems on the off chance I'd grow ambitious in the little kitchen and maybe cook a chicken.

I gave up on the rosemary and turned toward the stairs that led down to my suite. That was when I spotted a cat walking behind a man. They were on one of the footbridges connecting the top tier of rooms, in back. Some suites are permanent apartments with tatty screen doors and potted plants and other domestic touches along the balconies. The man was pale— hair, skin, voice, stooped posture, he looked to be a full- time renter with a noticeable Californianess about him, a certain stratum of weed smoker with few ambitions.

When you've haunted as many hotels as I have you spot the underlying characters, the tensions, the esprit de corps— or lack of it— among the workers, the essence of an establishment by the quirks encountered. The cat was striped rust and black, with splashes of white. Pale Guy said yes when I asked if the cat was with him. I said, "Hey, Kitty," in a high- pitched, girlish voice. "Hi, Kitty," I repeated quietly, remembering Joe and my long- gone sister cats. I thought of telling Pale Guy I loved cats but moved around too much to keep them— though that was more my former working self. Thankfully, I held my tongue. I did say, "He doesn't run away?"

"Not when he's hungry."

" 'Bye, Kitty," I said, half wishing the cat would follow me instead. I'd put out a saucer of milk, buy a can of tuna, make a little bed in the corner. Pale Guy continued on his way, Kitty in tow, tail hoisted high. I guess they've seen enough guests come and go not to bother. Pale Guy and Kitty were nuggets, though, not gold, but solid pieces of the texture of the hotel. I looked down and saw the rosemary right there at my feet. I bent to pinch a stem, thinking, as I always do when I pilfer flowers, if everyone did this there would be none left.

The Hotel Muse is old by Hollywood measure, a nightclub originally, from the late '40s, featuring acts better suited to a cir cus sideshow. The hotel was added later. Halfway up the hill is the upper part where we are situated— modest cousin to the main hotel on the avenue. It's the director's whim that his wife and principal crew (mostly imports from the East Coast) be installed up top, forming a kind of colony. Andre likes the availability of his people grouped together, but there are fewer amenities up top. Be low, the pool is heated; Turkish bathrobes, wireless, DVDs, and cable are provided— perks for those who prefer sanitized luxury. With us scruffier sorts above, services are hit- and- miss; no DVDs or wireless. Internet and breakfast are had by trekking downhill to the main lobby area, laptop in tow. The lobby is small so most mornings Internet users from uphill gather around the pool, rain or shine, chill or warm, huddling under patio umbrellas. I've noticed a number of German film types at breakfast. They talked loudly on Skype as they pace, necks swathed in scarves, woolen caps pulled low.

Andre's quirks usually pay off. I like his crew, and the arty types up here, for once inheriting the earth— or the spectacular view, anyhow. Our outsized, east- facing balcony overlooks a coral tree where wild green parrots squawk and screech each morning among the bright red flower petals. The landscape reminds me of the south of France, houses and villas tumbling steeply down the hills in a hodgepodge of styles, an architectural balancing act. The view to the right veers neurotically into L.A.'s urban sprawl and the sudden verticality of downtown. Straight ahead I can see the gray dome of the Griffith Observatory. On mornings when fog or the yellow- brown curtain of smog lifts, the San Gabriel Mountains are visible, snow- capped and reassuring in the distance. Brown- dotted hills segue into mountains in snow, urban and wild in the same snapshot. I hear there are lions in those mountains. I look out each day and imagine the city living on borrowed time, that the earth under Hollywood will someday shift and shrug houses and people, the observatory, trees, birds, coyotes, squirrels, cats, snakes, and everyone's dreams off the hills into the yawning abyss.

Another day has passed— faded meaninglessly into evening. I went outside for the sunset. The wind and chill were sharp up at the benched pavilion. Someone had taken a rake to the grounds; the condom was gone, and the narrative seemed lost without it. Over my shoulder a stream of distant planes flowed silently from the east, into LAX. To the west a slip of the Pacific Ocean shone like a piece of broken plate under a limpid sky. When the earth finally does shake the hills loose, the ocean will flood the coast and slimy sea monsters will roam the earth, lapping at the fallen city's face.

That's what I was imagining when I saw that the old gray man and his dog were back. He's been there every evening I've come up. He stood below the condom pavilion, at the top of the restaurant parking lot. His dog, an ugly black- and- brown pit bull, stared up at me. The grizzled man never turned my way, if he knew I was there. I made a friendly little click toward the dog, who continued to stare. I thought the old man had libation with him, a jar with purple remnants, communion with the setting sun. He was not a guest but arrived by a narrow path through the undergrowth outside the chain- link fence, past the pool. I'd thought of disguising scotch in a coffee mug to carry with me as I bade the day adieu but had decided I'd reward myself when I returned to the rooms, chilled from my own sunset homage.

Walking back toward the pool I heard voices, customers from the restaurant, the cocktail hour officially on. Asian tourists held cameras, peered toward the west, murmuring their pleasure; a night out on the town, living it up, spending plenty of yen. I wanted to slip out of sight (tricky since they were above me with a clear advantage), feeling like the old man, pretending I was alone to keep the moment to myself. I had a friend once— no, he was a writer pal of Joe's, a lanky poetic type who said I was a hoarder of moments. Maybe that's true. As I turned at the waterfall at the top of the stairs, heading down to my rooms, the kitty ran out in front of me.

" Where did you come from?" I said, bending to pet him. His purr was a minor roar. He sidled along my legs, rubbing around and back again. "Want to come home with me?" I asked, kneading my fingers through his thick fur. He followed as I veered back to the pool, then ran up a squat tree with perpetually shedding purple flowers, showing off. I watched for a few minutes, but he didn't follow when I turned to go.

Back at the rooms I poured myself a proper scotch— two ice cubes— into one of the glasses I'd purchased for the purpose. I went out to the balcony, the cashmere shawl Andre had given me the previous Christmas over my shoulders, Mexican- serape style. The last orange traces of sun were leaving the tops of the hills, the houses below already deep in shadow. The observatory held the golden glow longest, and then it too dimmed to a colorless form. I saw, across the hill, that the man was there in his garden.

I have been watching the man. I call him White Shirt because white seems to be his preference. His house is perched on the hill pretty much dead opposite my balcony, on the other side of a steep arroyo. It's French country style with a blue front door. I'd trade a toe for my binoculars back in New York. I could buy a pair here but that seems as if it would be cheating. My method of hotel discovery is slow, hints here and there, bits of life: an outdoor umbrella shifted, soft illumination from a nighttime window, the glow of a television or computer screen flickering in the middle of the night. I tried to drive up White Shirt's hill yesterday but got lost winding my way, ending up on Mulholland, at the top of Runyon Canyon. I parked the car in the small unpaved lot. A sign at the entrance warned of rattlesnakes. I walked alone along a dirt trail in the baking- hot sun until I came to one of the pinnacles. I could have been anywhere; the view shifted from angle to angle and felt foreign. Nothing was clarified, but I'm in no hurry. Things reveal themselves in their own time, time being a commodity I currently have to spare.

White Shirt was the first sign of life on that side of the hill. There is another house, a large two- family Spanish style. I look down on its backyard, where a lollipop- shaped tree is lit up each night with white lights. There was a cocktail party one evening on the patio, which I enjoyed watching, but the people in that house don't interest me. There is a chewable normalcy to the "Spanish Heights" house, something too obvious. White Shirt does interest me. His house is on the other side of the street from the Spanish Heights, and his yard is a square, grassy plot on top of his garage. One of the garage doors— white flap- downs— is broken; a dim light stays on all night over a white sports car.

White Shirt is home a lot. So am I. I watch him as David watched Bathsheba, though so far I am not lusting. Without binoculars I can see only that he is tall and slim with a full head of light brown hair. He must know he faces a hotel with large balconies; he must know he can be seen. In the Bible story David was supposed to be at war with his men; it was spring, the time kings went to war. Full stop. Why would kings, as a matter of course, go to war in the spring? Anyway, David was up on his roof prowling in the wee hours, and Bathsheba was up on hers having a late- night bath. Did a full moon illuminate her wet alabaster skin? Why was she bathing at that hour? Were they both insomniacs? Her husband, Uriah the Hittite, was at war, where David ought to have been instead of spying on bathing women. He sent one of his servants to invite her over. He was king, so his was probably an invitation one literally could not refuse. What did he want? Come lie with me, Mrs., we will have a grand old time.

The Bible doesn't bother with her take on the situation, other

than mentioning that Bathsheba cleaned herself after the act. We are not told if she tried to beg off with a headache or if she was flattered; after all, this was David who slew the giant, handsome, powerful King David. Did she love her husband? Uriah was a dedicated warrior; perhaps she felt neglected. Soon after David lay with her, Bathsheba let him know she was with child. David hadn't thought of that, apparently, but he figured he'd bring Uriah back from battle and pin the child on him. Go to your house, he told Uriah after faking a query about how the war was going. But loyal Uriah slept outside the palace doors that night. His men were in harm's way; his king and liege had spoken to him, quite the honor; this was no time to be dallying with the wife in the comforts of home. The same thing happened for two more nights, even after David got him drunk. Uriah was loyal to a fault. His wife might have thought so even before David seduced her. The story soon took a bad turn: David saw to it that Uriah died in battle, and then God killed David and Bathsheba's newborn as punishment. Bathsheba paid, but we don't know exactly for what: the unsanctioned dalliance with David or her infidelity to Uriah. The God of the Old Testament didn't seem to finesse the details when demanding his pound of flesh. Things eventually worked out for David and Bathsheba—

Andre! He came in just now, all a flurry of breathless, manly purpose, surprising me on the balcony. White Shirt had just gone inside his house.

"Let's have a drink," Andre announced.

"I'm ahead of you," I said, walking inside, drink in hand. I turned on the news, trying to mask the flutter in my stomach— a signal of any number of reactions to this unscheduled arrival of the director for a drink with his wife. Did he have time off the set during a complicated lighting shift . . . or was something wrong that he could leave, or had he said he'd have an early night and I'd forgotten?

It was a hurried drink. A drink should never be hurried. "How you grace me with your presence!" I spoke to his back as the door closed. He left with the bottle. He'd come for the bottle, the drink a nickel's worth of his time bestowed. Was his leading lady thirsty?

They are shooting close by, close enough for me to drop in, which he said I should do. But I won't. I would be treated on set like the general's wife. There would be curious stares and fawning over his onetime lead, the actress who took best prize at Cannes under his direction. The unanswered question always hovering: Why did she retire early, still in her prime, when the full blossoming of her breasts tantalizes most and she begins to understand her craft and to take bigger risks— why? Were the producers already casting about for less ripe, more malleable girls with dreams of stardom; was that it? Andre insists the lead is in me yet. Ha! I walked away of my own free will. Why would I walk back into that insecure cesspool of chattering facades called acting?

Andre doesn't like that word, insecure. He says it's overused, a catchall excuse for lack of discipline.

"Wobbly, then," I said back. "People are wobbly in who they are. You might try to be more sympathetic."

"Rubbish." It could almost have been Joe talking. But Joe would have qualified the retort by saying that the system of civi lization discourages personal strengths, the better to control a populace.

I stopped myself from throwing my drink at the door behind Andre. Wasted! I am wasted on peasants. If I came at you, dear audience, full force, you couldn't withstand me, yet Andre can crush me with a glance, like a rose petal under heavy boots.

Between Joe and Andre there were others. Once Joe and I bled dry, were wrung out, twisting in the winds of our failure, others entered the void. I was all alone in L.A. We didn't want to split up a pair of sisters, so Joe kept the cats, old by then but missed terribly, and I would not replace them. Harry kept me busy. He bent over backward to make the physical part of my move painless. It wasn't. He secured invitations to the important parties. That was hell. It was all I could do to keep from finding the broom closet until enough time passed to head for the door, get into my car, and drive home. I'd bought a brand- new compact to spirit me across the vastness of Los Angeles. I sublet a furnished bungalow on Gardiner Street, up in the hills— not too far from where I am now— and hunkered down among the chintz upholstery, shades drawn. I napped a lot, like a three- year- old, or I paced the small, secluded garden draped with intoxicating jasmine, surrounded by tall eucalyptus trees. I went for walks and absorbed the stares of the locals for doing the unthinkable, using my feet on the pavement. I detested L.A. at that point with all the strength my newly single sorry soul had available.

Dottie was my one solid friend. We were an odd mix. She was much older and very overt. Singers are a different sort of showman than actors. She started out doing radio jingles in Wichita, then went east, played the Rainbow Room, other high- end New York nightspots. Dottie was auditory color; she'd made a brief splash in a tough town. She told me she was born with perfect pitch. "That was God's gift," she declared. "I had not a thing to do with it." It was her Plains modesty talking; Dottie's no- nonsense values didn't always fit with her bright outfits and flamboyant theatrics. We had in common a shyness hidden by what we did for a living. With Dottie it was Kansas proper— no one out in all that open likes a show- off, she'd say— though she could ham it up pretty good at the piano. I was shy at the bone. If you scratched Dottie, you scratched dirt, where corn or soy or wheat comes from: solid earth, simple and clean and probably conservative in ways I might not tolerate if Dottie wasn't a chanteuse. Scratch my surface and you get blood, guts, darkness, and dumb hope.

She sang Noël Coward ballads and old show tunes with flare but not a whole lot of depth— the material didn't encourage it. She worked sporadically. A well- off husband died, leaving her comfortably placed. About Joe she said, sensibly, "Ard, honey, the boy who'll follow a girl around the world hasn't been invented yet. They'll calve before that happens. You had no choice. Or yes, you did: It was you for yourself or him." Why'd I have to choose at all? Joe hadn't given me an ultimatum, and I hadn't given him one. I was wracked with doubt. Should I have moved out west, put my career ahead of Joe? Was Dottie right: Woman follows man? Was I doomed to die alone?

I hit bottom, started turning down jobs, refusing phone calls. Harry was ready to work me over with a whip. He called to tell me Andre Lucerne was looking to direct another feature; he wouldn't cast me in the lead this time but was offering a strong supporting role that was mine for the taking. I said no, thanks.

"You're turning down Andre Lucerne?" Harry said. "Help me here, Ardennes."

"I'm not turning down Lucerne. I'm turning down the location. Stockholm in winter, Harry? It's too far away. I'm just not ready." Harry snorted his disbelief. "Okay, I don't like the part either."

"You're wrong; that part is a perfect vehicle for you. And Stockholm is glorious in winter. Lucerne himself called." This time I snorted a so- what. " Never mind." Harry said all calm business. "I'm giving you one month to finish suffering and then I'm dropping you."

"Harry . . ."

Dottie said what did I expect; Harry wasn't my uncle. She didn't let on how worried she was about me hanging around the house all day with a bad case of the guilty blues. She'd take me shopping or come over and make us cocktails, sing ditties until I'd smile, which was about all I could manage, and that was mostly polite. "Dear girl, that sea is loaded with fish, you just have to dive in and pull. And for heaven's sake climb out of those tired old pj's and get outside. Go back to work!"

I wasn't sure if Harry was bluffing or if he'd really drop me. I also genuinely did not know if I'd ever stand in front of a camera again. I wanted so badly to call Joe, tell him that I'd made a terrible mistake, that I wanted to come home; I'd go back to stage acting and our life together, forget all about Hollywood. But he didn't call either and I think that was what hurt the most, that he could just do without me. He'd had a lot of practice, Dottie pointed out, all those absences, me out here working among the fleshpots of Southern California. But Joe didn't doubt me in that way; he was the surest guy I ever met. In the end I think he just didn't want to be married to a movie actress.

Dottie said it was not what she had in mind when I started going around with a friend of hers, a steadily employed character actor in big movies. We met at one of Dottie's rare singing dates. For a couple of weeks she was the closing act at a club that specialized in after- hours drinkers, well- off layabouts, a crowd that ate up her songs, was never loaded to the point of clamor, and by closing time would be singing along, adoring Dottie and their carefree lives.

Like me, Fits (that's all anyone ever called him except in movie credits, where "Matthew Fitzgerald" scrolled across the screen) didn't fit the cabaret scene. He didn't know the lyrics to Dottie's numbers and flat- out hated show tunes. We were there for her, and maybe the generous drinks. Fits was not my type. He was heavyset with sandy, graying hair scattered like buckshot over his head, and a good number of years older. His small eyes had an ironic twinkle belying the rough kindness of his nature. He was unexpectedly light on his feet and sexy and, at that particular moment, the best shoulder in the world for me to cry on. Like Joe, he had radar for injustice and a healthy sense of outrage. And, like most actors I know, he was on the lookout for injury, his ego on his sleeve, finding slights where none was intended. His main complaint, besides rarely getting the lead, was not enough camera time. I've never met an actor who didn't have that particular complaint. But it wasn't something he got ugly about, or only fleetingly, and not a true disappointment. When I met him he was cleaning up. He said he'd wake up not knowing if it was the booze or the coke from the night before that made him feel like slow death each morning; he'd decided he did not want to live that way anymore. He was divorced— twice— who isn't in Hollywood— and the father of a kid living problematically with her mother, which added worry and increased the booze- or- cocaine or cocaine- or- booze routine— whichever it was. He wanted to be able to account for his nights and learn to let things be: his acquired wisdom; very L.A.

He teased me that night for being so young and pathetic, and for being Dottie's friend. I pointed out that he was her friend too, but he said that was different and went on calling me a child and so on until I finally asked him to dance with me just to get him to shut up. His elegant dancing took me very much by surprise. I mean, Fits could waltz. I'm a closet dancer. I respond to music; even dumb, sentimental twaddle wafts its way into my skin and my hips begin to sway. Joe mocked dancing unless it was exotic, by which he meant Indian or Indonesian, not lap. Dancing was a bourgeois pastime meant to allow repressed people to touch, he said. He did learn to watch me improvise at home, to jazz mostly, saying it was probably necessary for an actor to be connected to the body in that way. Once in a while we played at striptease. Ah, Joe.

Anyhow, Dottie was singing a Gershwin tune that night I'd forgotten requesting. She didn't know all the lyrics and said so, sticking the blame of her attempt on me. The song was "Someone to Watch over Me," and I hummed along in Fits's ear as we danced, fighting down tears. He chuckled, his loose frame wobbling in my arms. "Don't laugh at me," I murmured.

He pulled back to look into my face. "I would never laugh at you," he said. "At the song maybe, but not you."

I looked back to see if he was fooling with me. He wasn't. I moved to the music, not even needing a partner. "Who's leading?" I asked.

"I always lead," Fits replied.

It was a Hollywood moment.

He took me home that night. Dottie had insisted I take a car service to the club, though it was not far, down on Fountain, I think. I didn't drink that much anyway and could have driven even if it was three a.m. and I was weary. So Fits took me home in his beat- up Beemer and came in and made himself a pot of coffee, and we sat up in the bungalow for what was left of the night and talked. He was contrary and proud and not easy, but he was the right guy that night. Underneath a fair amount of armor, my soul was safe with Fits.

He was full of stories, having arrived on the scene just ahead of AIDS slowing down the Hollywood sex- press. He'd been skinny— believe it, he insisted— fresh, raw meat. "This one time I was invited to this A- list actress's house [he wouldn't name names, but I guessed] about a part in a movie. She'd lead and produce, so it was kind of an audition. I wanted the work bad— not a great part but solidly supporting: a dumped lover she keeps around for play. Got the idea?"

I did.

"So I arrive at her Brentwood manor house and I mean castle and the butler or assistant, whatever they were called then, asked me to wait and this monster dog runs up and pins me to the foyer wall. I mean paws up on my shoulders, standing taller than me and he could make lunch out of my arms, steamy dog breath all over my face. The servant comes back and leads me (and the dog) to the 'spa,' meaning the bathroom— big enough for a New York studio apartment. And she's in the tub under a blanket of bubbles and I sit on a little fluffy chair thing and the dog sits too and soon she wants me to hand her her towel. I begin to wrap it around her and the dog goes into protection- mode pacing and I'm scared to shitting and she says, Good dog. And I'm thinking I don't want to die for this part or be maimed either. Next thing she opens a door off the spa and we're outside in a garden overlooking L.A., spread like jewelry before us, and she sits on a chaise naked as Christmas and her legs are open. She pulls me down, I trip, the chair topples, and the dog goes into a crouch, ready to spring. She calls me a klutz and shoves me off and I figure that's it, I blew it, I can go now, only she goes into another door which is to the bedroom. I stand there until she asks what I'm waiting for. The dog is looking at me like with the same question and in we go. She's on the bed and there can't be much doubt why. Some audition, she says, and I'm, Okay I get it now, and I'm in that fast. Just as I get the rhythm going the dog jumps on the bed and begins to lick my ass. And he's heading underneath. I don't do animals, so I'm done, my rod wilts and I'm outta there. She calls me a queer as I pull on my pants fast as I can. I slam the bedroom door on the dog and find my own way to the exit." He took a breath.

"Did you get the part?" I asked.

Fits sipped his coffee and grinned. "It was a wild town back then." The sky was beginning to give up the night; wan morning light filtered into the comfy living room. Fits lay back in his deep- cushioned armchair. "So you want to be an actor," he said just as I sat up straight on the couch.

"What's the big idea? I am an actor! I just wrecked my marriage for acting. Jeez."

"Okay, take it easy. So you have some creds, that's nice, but you're only at the beginning of the journey."

I didn't think that was true but saw no point in going into it, digging up the past. I won Cannes; didn't he know that? Did he expect an argument, a defense? But Fits was a tester of waters. He said things to jolt, to get a person to reveal herself, pokes here and there until an opening appeared into which he'd shove little mind swords to see the stuff a person had inside. "So what if I was only starting out?" I said, chin forward. " Which I am not."

"So nothing,"

"Okay. All right, Mr. Seasoned Movie Man, what is acting?"

He grimaced, leaned forward, his overly full top lip briefly curling upward. "What is fucking?"

I thought a minute. "Fucking is listening."

"So is acting."

It didn't start that night, but before long I was listening closely to Fits. I don't know how much he listened to me. We were not in love. Well, Fits was in love with the idea of love, his head turning at every pretty girl. I was briefly jealous, only because I was so bruised and Fits was the life jacket I'd been thrown. He would not let me cling, though. He would not let me betray myself that way in him; he was too honest for that. The world really doesn't forgive a broken heart, or at least not the mourning of it. In a way Fits was just the tonic. There was something about a guy with more experience under his belt that allowed me some perspective, even to laugh at myself. If I was moving in the direction of success, all that seemed to be required was my heart. Fits may have been my life jacket, but I didn't have to take us too seriously. That was an education. I don't think I would have pulled out of that funk without him; I'm not suggesting I ever could have done it alone, but he showed me how to let things be what they were. Good old Fits.

Quickies have checked into the room below— one- or twonighters— joyriders, boisterous and looking to party. Heavy- metal rock vibrates through the floor with a pounding refrain: Let it rock, let it rock, over and over. Is someone being pounded on the bed in time to the pulsing beat? I'm guessing a dusting of cocaine residue on the nightstand. It might be a good time to hit the hotel laundry downstairs, make a dent in the pile of dirty clothes mushrooming in the closet, but, nah, the mess can wait till morning. My grandmother used to say never do wash at night; you can't see the dirt.

The lovers must have gone out around midnight because I was kept awake until then and was asleep when Andre came in from his night location. I heard him climb into bed and held very still, careful to keep my breathing even. I don't know if we are going to make it, he and I. I'm a grass widow anyway. Andre is entwined in the undergrowth of a movie set, the miniature universe, the womb and birth and life of filmmaking. I know it firsthand. He's faithless anyway. Usually not when he's directing; the film is Andre's mistress then. But he's a director; actresses fling themselves in his path. Casual cupcakes of an afternoon, dalliances, the poor starlets: paper peeled off, icing licked, maybe a walk- on part.

As I lay pretending to be asleep, I thought maybe my dad had named me wrong. I should have been called Retreat. Or did I desert— as in abandoned my post? A retreater finds safety to gear up and return to battle. Deserters are shot. How did my dad get out of the Ardennes alive? He was awarded the Silver Star, which is given for gallantry in battle. Gallantry? I don't even know what that word means. They didn't call it gallantry in 1945. It was simply heroism. Why the change? He was twenty and promoted to captain because they were running out of captains by the hour. He told the few men left under his young command that no one had ordered them to die in the frigid winter woods, so they aimed at anything in gray and scrammed out of there. It was a retreat; he got them out alive. If they'd planned to desert, presumably they wouldn't have gone back to whatever base camp there was. Were they gallant men? Am I a deserter?

Andre was out cold next me. He'd throw a pillow over his head and that was that. I wondered how he could handle all the pressures and energy and concentration of directing a movie and just crash like that as soon as his head hit the pillow. He hasn't an ounce of nervous energy. I, on the other side of the California king, was wide awake, a jangle of free- floating brain waves trying to pass themselves off as thoughts.

After I turned down the part he offered me, I learned— back when Fits and I were briefly an item— that Andre had been intrigued by my refusal to work with him a second time. He doesn't direct many movies. Producers despise what they think of as his arrogance, but his films reach a steady audience, an arty following here and in Europe and Japan, and the classier critics love him, so he gets his financing. Word is he'll do anything to get a movie the way he wants it. He's co- written two of his films but is not a writer; Joe wouldn't say so, and I would agree. He's visually brilliant, his characters never less than vivid. He's been called the poet in Godard combined with the bite of Clouzot and the careful structure of Lumet. As a director he is exacting and manipulating and doesn't allow his actors to run loose, even undermining their control over their characters— which scares most actors pantless. Anyhow, I heard through an actress who had a small part in Separation and Rain that Andre was amused. "It just doesn't happen," the other actor, Mindy Scott, told me. We'd met for coffee at a place near the Beverly Center. "Is it because it's not the lead? I have to ask, I mean, are you all right? I personally would do any part of Andre Lucerne to work with him again. I'd do it even as an extra. I mean, Andre Lucerne's the greatest director alive right now."

"You really think so?" I asked. Word on set had been that she'd couch- auditioned her part. I smiled, and suddenly Mindy's eye contact wasn't so steady.

I called Harry the next day. "Did I kill it with Lucerne by de clining?"

"Interestingly, no," Harry said. "But you can't change your mind now."

I was biting my nails. "But I blew up that bridge, huh?" I was getting pretty good at blowing up bridges.

"That's not the way I hear it. Are you ready to go to work?"

"Soon, Harry . . ."

Fits laughed when I told him. "Good for you; these directors

can get to thinking they're gods," he said. "Be careful, though, not to turn saying no into a self- destructive pattern."

He had just wrapped a movie and had time on his hands. He said we should go to Mexico. There was a place, San Quintín, about a third of the way down Baja; he'd go fishing and I could ride horses on the beach. I'd never been to Mexico so I said okay, and we took off that night. Fits drove straight through to Ensenada, where we spent two days in a hotel on the harbor. He taught me how to drink tequila; he'd watch, buying the rounds as I downed one after the other. I discovered real Mexican food and fell for tacos, stopping at every taqueria we passed. Things didn't go so well in San Quintín. The place was beautiful but empty. We had the off- season hotel almost to ourselves. I felt far away and panicky. I felt far away all the time, but this was worse. When the divorce papers came through I felt far away, detached, unmoored and scared. They cited abandonment, meaning I had done the abandoning. I called Joe, my voice weak and drained. He felt lousy too, but I said he at least had the advantage of being at home with the cats. He said the place was full of the ghosts of us, and I cried into the phone. I'd begun to forget what I was so far from as Los Angeles asserted itself, but that open, lonely, windy beach with the seagulls screeching mournfully was too far too fast. I told Fits I had to go back, I'd freak if I didn't get to someplace familiar. He said to quit carrying on like a bad acid trip but agreed to take me back to L.A. the next day.

That time in Mexico was the beginning of the end of me and Fits being physical together. We did become good friends. Fits is basically a loner; he just let me borrow his world at a time when mine was crumbling around me. Once I got back into the swirl, once I let the business take me over, figuring, finally, the thread between me and Joe was truly snapped, and my heart got a nice big scab over it, there were lovers. Some I remember their names but not much else. At least one turned stormy— on his part. One almost got to me. None were ever as kind as Fits.

The morning after I got back from Mexico, I picked up the phone to hear Andre Lucerne's voice on the other end. I was still undressed at eleven, probably hadn't brushed my teeth, sipping tea in the kitchen, my stomach wrenched from too many tacos and tequilas. I thought maybe it was Fits fooling around, but he'd made it pretty clear we should let a few days pass without seeing each other. I told Andre I was sorry for turning down the part and was about to drift into the untouchable topic of my recent divorce, but he wasn't interested. He asked me to dinner.

"Dinner?" I repeated, biting my tongue from adding, why? He'd hardly given me a second glance when I'd been his lead. He'd gotten the performance he wanted and hadn't bothered with the on- set nice- nice- let' s- get- to- know- each- other groove. All the actors were terrified of Andre, though he was never genuinely mean or bullying. He was not so much distant as preoccupied, as if each day was profoundly itself and there was only time and energy enough to make it brilliant; all else was distraction and waste. You felt you had to please him, to try to break through and capture his approval, which usually came in the form of a nod and, if really pleased, a nod and slight raising of his eyebrows. If the eyebrows dipped and he fell silent you knew you were miles off course.

Why was he bothering with me now? Besides the fact that he was married and twelve years older— a very attractive twelve years— and I'd said no to his movie.

"Dinner, yes. You do eat dinner?" he said.

"I do, but . . ."

"Free tonight?"

As a bird, but there was my stomach and . . . and did I want to have dinner with Andre Lucerne? "I was in Mexico for a few days," I said, "I— I'm a little out of sorts."

"Ah, the tourista. Drink some tequila— hair of the dog— and swallow raw garlic cloves; you will live."

We set a date for the following week and met at a little Moroccan place in Los Feliz, a café, very relaxed. I nearly got lost finding the place. Andre had lamb. I hate lamb, so I ate a tabouli dish with hummus, baba ghanoush, and some sort of spicy fish. He did nearly all the talking. He told me his theories on film, which were vast and contradictory. I started thinking, at heart he's an anarchist— if he isn't nuts— all the while picturing Joe making faces behind his back, as in Who is this guy? Possibly he noticed my concentration wandering and got off theory and told a very funny story of the making of his first film and how he hadn't really intended to be a filmmaker. "I think I would have preferred to be a painter," he said, as if the idea had just come to him and I was not seated opposite, listening. "If only because with painting one can erase. One is freer. There are too many details that can barely be controlled in making films."

"Like the actors?" I ventured.

If he heard me he didn't react. The café sold Moroccan items: pointed leather slippers, clay tagines, spices, even clothing and mother- of- pearl combs. As we were sipping our mint tea and coffee after dinner, Andre abruptly walked over to an armoire that had a sumptuous gold- threaded white caftan hanging on the open door. He brought it to the table and told me to stand and hold it up. "This would fit you perfectly," he said. I couldn't help noticing the three- hundred- fifty- dollar price tag. Calling for the check, he told the waiter to add the caftan and wrap it up. He gave me the package out on the sidewalk.

"For me?" I was embarrassed by his extravagance and what it might imply for the rest of the night, but all he did was kiss my hand.

" Thank you for your silence; it's a rare gift these days. I enjoyed our dinner."

(I have a gift for silence?)

That was it. Assured I knew my way back to Hollywood, he said good- night. I didn't see him again for nearly two years. He was right about the caftan; it fit as if it had been custom- made. That café became a favorite of mine, but not sentimentally; I had no idea what to make of the evening or why Andre wanted to have dinner with me. As far as I knew, he went home to wife number two, an actress, that night.

In the morning I got up whisper- quiet, not to waken Andre. I made a pot of tea to drink on the balcony as I idly watched for signs of White Shirt. There were none. The day was bright, clear, and almost cold. I could see snow on the mountains. Without the sun, now well over the San Gabriels, I would have frozen stiff. The caftan is here with me, in L.A., and I look for excuses to wear it. I wonder sometimes if in his mind that Moroccan dinner was the start of Andre's courting me. The next time we met he referred to the evening as if it had taken place the week before. The caftan is meant for a Park Avenue apartment with a cascading marble staircase, for descending à la Loretta Young, swishing to greet guests for cocktails or late- morning confidential chats in the boudoir. I have neither cascading stairs nor a bedroom fit for an heiress, and no Fred Astaire type arrives of an evening, the butler showing him in. The garment is of another era. Joan Crawford comes to mind.

Too bad it wasn't with me when I won best actress at Cannes. Andre was up too, for best director, for Separation and Rain. He didn't win, but his leading lady did. The French adored Andre, and Cannes had already awarded him best director, so he was relaxed either way. I nearly threw up when they announced my name. I didn't even have a new dress but an old filmy thing I'd had around forever that I wore to every event. I jazzed it up with a silk shawl I'd seen in a shop window along the Croisette, which Harry surprised me by buying. Mindy Scott showed up in Cannes, scraped the money together, she said, to fly over for the festival and was hanging on to me like skin on bone. She'd had all of three lines in the movie. She must have told Harry about the shawl, and I figured he must have paid her way over, probably to keep tabs on me, though Mindy was not his client. He'd wanted to buy me a new dress, but I'd refused. I told him to forget it; I was not going to win and not to waste his money. I shocked him by getting my hair cut très short. I walked cold into a salon and said, "Take it off." It looked great, if I do say so myself. Harry of course pooh- poohed the style. "Eurotrash!" he called it.

Cannes was a disappointment; the town, the film festival, even the fabled beach was a letdown. Beneath a glamorous veneer the festival was a flesh factory for selling cans of movies and careers. We had press nearly every day; Andre and the producers, the principal actors, interviews and photo ops to keep the excitement revved up. Andre was very nice, helped me handle the glare and field some of the numbingly inane questions the press threw at me. Mindy was practically my Siamese twin, so she made some press appearances too. I didn't fault her pushiness. I held on to her in the street, where we were trailed by a band of bored- looking paparazzi. Until I won; then it was a wolf pack of international camera snappers in my face, all part of the star machinery.

Joe flew over after I called to say I'd been nominated, making it to Cannes one hour before the ceremonies began. At least he wore a black sports coat over his jeans. He loved the hair. "Very gamine," he said in my ear. Cannes disgusted him as much as it did me. The water off Nice looked polluted from the plane, he said, like a milky stream of sewage pouring in next to the bathers. The road from Nice to Cannes was littered with an obnoxious string of minimalls— not Big Mac and Burger King but pan, pizza, poulet joints— fast food French style. The Ritz, where Harry had put me up, was over the top. Even the coffee shop was a four- star deal; luckily the room came with breakfast of croissant and bowls of café au lait. Joe asked if they didn't have a Motel 8 or something like it near the airport. I was worrying about how he was going to take all the after- ceremony parties I'd have to attend— de rigueur— just because I'd been nominated, so I didn't hear when they announced my name. Joe nudged me. "It'll be all right," I said. "We'll pop in, say hello, and scram to the next party, ten minutes each, max."

"What are you talking about? You won, silly goose." He held and kissed the palm of my hand. I stared at him. They said my name again, and I felt myself stand up among the audience as if I were being lifted on an ocean wave, my stomach bucking. Suddenly Andre was there, kissing both my cheeks, his hands on my shoulders, nearly knocking off the mauve shawl. Harry was squashed into a seat two rows behind me; he pushed himself up to come embrace me, his breath wet in my ear. An usher appeared to guide me to the stage. My legs were rubber doll's legs. I faced Joe with a get- me- outta- here look. But he was applauding along with everyone else. I didn't figure I'd have a snowball's chance in hell of winning so I had nothing prepared to say. One of my idols, Giulietta Masina, won best actress at Cannes— for Nights of Cabiria— was I worthy of her? Some genie moved my hands for me, tossing the shawl gamely over one shoul der, leaving the other bare, the strap of my dress slipping ever so slightly. Joe said later the hair and subdued sexiness of the shawl worked magic. The French papers next day exclaimed over my chicly original sense of style. Ha.

I stumbled through a thank- you. I felt I wasn't breathing. I kept my eyes down and spoke just above a whisper, thanking Andre and the cast and Harry and the producers and, oh, the French, "Viva La France!" popped out of my mouth, eliciting a puff of laughter from the crowd. I felt the surge of their energy: an almost out- of- body sensation. I paused and looked out at all those faces, just for a second. It was like firecrackers lit just for me, ten thousand fireworks and I was the Fourth of July; a thousand flaming torches— all for me. It was madness. Finally, I thanked the writer Joe Finn.

He was furious. We were up all night arguing after the parties Harry dragged us to in rapid succession. Joe had steadily downed the drinks, whatever the waiters were passing around. I watched him nervously; Joe wasn't much of a drinker. Back at the room I burst into tears. At one a.m. Andre called: Where was I? The big Separation and Rain celebration was just warming up and the star was missing. He sent up a bottle of champagne. I had the waiter open it, though Joe stood there glaring like poison. I went down to the party alone, a study in misery. Once again Andre stepped in, was gentlemanly and solicitous, guiding me through the night.

The next day Cannes was dead, a ghost town. Everybody was either in bed hungover or on a plane home now that no one would pick up their tab if they stayed on. Outside, sweepers were at work as the locals reclaimed their town. Harry woke me up with a phone call at noon: Why wasn't I at the airport?

My head was splitting, my mouth like old chewing gum and sawdust. "Can you change my ticket to a few days from now, please, Harry, and please don't ask me any questions."

"It's that moper, isn't it?"

"That's a question, Harry. Just please work some deal with my first- class ticket, cash it in for two coach fares back to New York in, say, four days. I'm begging you, Harry." I hung up.

We rented a car and drove up to Aix en Provence, stopping at a roadside stand selling cherries— cerise— that were the plumpest, sweetest we'd ever tasted. " These aren't cherries," Joe said, holding one up. " These are tree- grown orgasms." He turned the car around and we bought another half kilo. We drank Pernod at the café Des Deux Garçons, where Cézanne used to hang out. We visited his studio, up past a housing- project slum outside Aix. Inside were the painter's props and his straw field hat and black all- weather coat hung on a hook by the door, as if he'd only just gone out. The very same leggy germaniums, still- life jars and vases; only fresh pears and apples were missing. We had the place to ourselves until a small troop of tourists filed in, cameras like appendages hanging off their necks. Even Joe thought we'd stood on something like hallowed ground that day.

We went to the market for fresh goat cheese, bread, fruit, wine, tomatoes, and olives for a picnic at the base of Mont St. Victoire. I recall stopping the car to pee in the woods, and the glassy light in the forest, the reddish tree trunks and a wash of silver in the air. I remember thinking Cézanne had seen that light and captured it on canvas. We laughed out loud arriving at the view he'd painted so many times, the tumbledown boulders of St. Victoire. I said to Joe, "That's it, that's cubism right there; he painted what he saw!"

"Good old crotchety Cézanne. And Hortense, his wife: the ball and chain," Joe said with a wink.

"Hey!" I shot back. "What about 'Theory shits,' what he said to his painter pals in Paris, Monet and Pissarro and the others, before he took off for the south, never to look back."

"A man who knew what he wanted and wasn't afraid to go after it," Joe said.

We worked to patch things up under that pale Provençal sky that seemed as if it could cleanse any human sin. I thought Joe was angry at me for thanking Andre and everyone else first at the ceremony, but he sneered at that. "Andre?" he said, exaggerating the name (Ahhhhhndray). "All right, the man has talent, but all Andre does is Andre."

I decided I'd skip that part. "Is this about you taking that electrical work? You don't have to."

" Really? You took an apartment in Los Angeles; now we have two rents to pay."

"It's just temporary, and I can handle both, Joe; it's way cheaper than a hotel." I made my voice small because money talk could cause an avalanche.

"Do you think about what you're doing, Ardennes?"

"Taking the apartment? I'll get more work if I'm out there. . . . I wish so much you'd come, just for a little while. The cats could fly out too."

"I'm saying: Is this what you want?" His tone was like a clamp on my throat.

"It's what I do, Joe; I'm an actor. It's just, I— what do you want me to do, act in documentaries?" I'd done everything in my life to be doing what I was doing; what was I supposed to make of Joe's question? Was I any different than Cézanne going after his art? "I don't see your writing saving the world from hunger—"

"—Just forget it!" he cut in. (That was his fallback position.)