Читать книгу Kidnap the Emperor! - Jay Garnet, Jay Garnet - Страница 6

1

ОглавлениеThursday, 18 March 1976

The airport of Salisbury, Rhodesia, was a meagre affair: two terminals, hangars, a few acres of tarmac. Just about right for a country whose white population was about equal to that of Lewisham in size and sophistication, pondered Michael Rourke, as he waited disconsolately for his connection to Jo’burg.

Still, those who had inherited Cecil Rhodes’s imperial mantle hadn’t done so badly. Across the field stood a flight of four FGA9s, obsolete by years compared with the sophisticated beauties of the USA, Russia, Europe and the Middle East, but quite good enough at present to control the forested borderlands of Mozambique. And on the ground, Rhodesia had good fighting men, white and black, a tough army, more than a match for the guerrillas. But no match for the real enemy, the politicians who were busy cutting the ground from under the whites.

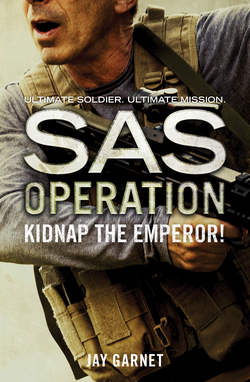

Rourke sank on to his pack, snapped open a tin of lager and sucked at it morosely. He had been in and out of the field for twelve years since first joining the SAS from the Green Jackets: Rhodesia on unofficial loan, for the last two years; before that, Oman; before that, Aden. In between, back to the Green Jackets.

The money here had not been great. But he’d kept fit and active, and indulged his addiction to adrenalin without serious mishap. At thirty-four his 160lb frame was as lean and hard as it had been ten years earlier.

But now he had had enough of this place. He was tired: tired of choppers, tired of the bush. The only bush he was interested in right now belonged to Lucy Seymour, who hid her assets beneath a virginal white coat in a chemist’s down the Mile End Road.

The last little jaunt had decided him.

There had been five of them set down in Mozambique by a South African Alouette III Astazou. His group – an American, another Briton and two white Rhodesians – were landed at dusk in a clearing in Tete, tasked to check out a report that terrorists – ‘ters’, as the Rhodesian authorities sneeringly called them – were establishing a new camp near a village somewhere in the area. Their plan was to make their way by night across ten miles of bush, to be picked up the next morning. Four of them, including the radio operator, were all lightly armed with British Sterling L2A3 sub-machine-guns. One of the Rhodesians carried an L7 light machine-gun in case of real trouble.

Rourke anticipated no action at all. The information was too sparse. Any contact would be pure luck. All they would do, he guessed, was establish that the country along their line of march was clear.

But things hadn’t gone quite as he thought they would. They had moved a mile away from the landing zone and treated themselves to a drink from their flasks, then moved on cautiously. It was slow work, edging through the bush guided between shadow and deeper shadow by starlight alone. Though they could scarcely be heard from more than twenty yards away, their progress seemed to them riotous in the silent air – a cacophony of rustling fatigues, grating packs, the dull chink and rattle of weaponry. To penetrate their cocoon of noise, they stopped every five minutes and listened for sounds borne on the night air. Towards dawn, when they were perhaps a mile from their pick-up point, Rourke ordered a rest among some bushes.

They were eating, with an occasional whispered comment, when Rourke heard footsteps approaching. He peered through the foliage and in the soft light of the coming dawn saw a figure, apparently alone. The figure carried a rifle.

He signalled for two others, the American and the Briton, to position themselves either side of him, and as the black came to within thirty feet of their position he called out: ‘All right. Far enough’. The figure froze.

Rourke didn’t want to shoot. It would make too much noise.

‘Do as we tell you and you won’t be hurt. Put your gun on the ground and back away. Then you’ll be free to go’.

That way, they would be clear long before the guerrilla could fetch help, even if there were others nearby.

Of course, there was no way of telling whether the black had understood or not. They never did know. Unaccountably, the shadowy shape loaded the gun, clicking the bolt into place. It was the suicidal action of a rank amateur.

Without waiting to see whether the weapon was going to be used, the three men, following their training and instinct, opened fire together. Three streams of bullets, perhaps 150 rounds in all, sliced across the figure, which tumbled backwards into the grass.

In the silence that followed, Rourke realized that the victim was not dead. There was a moan.

The noise of the shooting would have carried over a mile in the still air. He paused only for a moment.

‘Wait one,’ he said.

He walked towards the stricken guerrilla. It was a girl. She had been all but severed across the stomach. He caught a glimpse of her face. She was perhaps fifteen or sixteen, a mere messenger, probably with no experience of warfare, little training and no English. He shot her through the head.

He would have been happy to make it his war; he would have been happy to risk his life for a country that wasn’t his; but he was not happy to lose. The place was going to the blacks anyway. So when they offered to extend his contract, when they showed him the telex from Hereford agreeing that he could stay on if he wished, he told them: thanks, but no thanks. There was no point being here any more.

Now he was going home, for a month’s R and R, during which time he fully intended to rediscover a long-forgotten world, the one that lay beneath Lucy’s white coat.

The clock on the Royal Exchange in the heart of the City of London struck twelve. Two hundred yards away, in a quiet courtyard off Lombard Street, equidistant from the Royal Exchange and the Stock Exchange, Sir Charles Cromer stood in his fifth-floor office, staring out of the window. Beyond the end of the courtyard, on the other side of Lombard Street, a new Crédit Lyonnais building, still pristine white, was nearing completion. To right and left of it, and away down other streets, stood financial offices of legendary eminence, bulwarks of international finance defining what was still a medieval maze of narrow streets.

Cromer, wearing a well-tailored three-piece grey suit and his customary Old Etonian tie, was a stocky figure, his bulk still heavily muscled. One of the bulldog breed, he liked to think. He stuck out his lower lip in thought and turned to walk slowly round his office.

As City offices went, it was an unusual place, reflecting the wealth and good taste of his father and grandfather. It also expressed a certain cold simplicity. The floor was of polished wood. To one side of the ornate Victorian marble fireplace were two sofas of button-backed Moroccan leather. They had been made for Cromer’s grandfather a century ago. The sofas faced each other across a rectangular glass table. On the wall, above the table, beneath its own light, was a Modigliani, an early portrait dating from 1908. In the grate stood Cromer’s pride and joy, a Greek jug, a black-figure amphora of the sixth century BC. The fireplace was now its showcase, intricately wired against attempted theft. The vase could be shown off with two spotlights set in the corners of the wall opposite. Cromer’s desk, backing on to the window, was of a superb cherrywood, again inherited from his grandfather.

Cromer walked to the eight-foot double doors that led to the outer office and flicked the switch to spotlight the vase, in preparation for his next appointment. It was causing him some concern. The name of the man, Yufru, was unknown to him. But his nationality was enough to gain him immediate access. He was an Ethiopian, and the appointment had been made by him from the Embassy.

Cromer was used to dealing with Ethiopians. He was, as his father for thirty years had been before him, agent for the financial affairs of the Ethiopian royal family, and was in large measure responsible for the former Emperor’s stupendous wealth. Now that Selassie was dead, Cromer still had regular contact with the family. He had been forced to explain several times to hopeful children, grandchildren, nephews and nieces why it was not possible to release the substantial sums they claimed as their heritage. No will had been made, no instructions received. Funds could only be released against the Emperor’s specific orders. In the event, the bank would of course administer the fortune, but was otherwise powerless to help…

So it wasn’t the nationality that disturbed Cromer. It was the man’s political background. Yufru came from the Embassy and hence, apparently, from the Marxist government that had destroyed Selassie. He guessed, therefore, that Yufru would have instructions to seek access to the Imperial fortune.

It was certainly a fortune worth having, as Cromer had known since childhood, for the connections between Selassie and Cromer’s Bank went back over fifty years.

The story was an odd one, of considerable interest to historians of City affairs. Cromer’s Bank had become a subsidiary of Rothschild’s, the greatest bank of the day, in 1890. The link between Cromer’s Bank and the Ethiopian royal family was established in 1924, when Ras Tafari, the future Haile Selassie, then Regent and heir to the throne, arrived in London, thus becoming the first Ethiopian ruler to travel abroad since the Queen of Sheba – whom Selassie claimed as his direct ancestor – visited Solomon.

Ras Tafari had several aims. Politically, he intended to drag his medieval country into the twentieth century. But his major concerns were personal and financial. As heir to the throne, he had access to wealth on a scale few can now truly comprehend, and he needed a safer home for it than the Imperial Treasure Houses in Addis Ababa and Axum.

Ethiopia’s output of gold has never been known for sure, but was probably several tens of thousands of ounces annually – in the nineteenth century at least. Ethiopia’s mines, whose very location was a state secret, had for centuries been under direct Imperial control. Traditionally, the Emperor received one-third of the product, but the distinction between the state’s funds and Imperial funds was somewhat academic. When Ras Tafari, resourceful, ambitious, wary of his rival princes, became heir, he inherited a quantity of gold estimated at some ten million ounces. He brought with him to London five million of those ounces – over 100 tons. By 1975 that gold was worth $800 million.

In London, Ras Tafari, who at that time spoke little English, discovered that the world’s most reputable bank, Rothschild’s, had a subsidiary named after a Cromer. By chance, the name meant a good deal to Selassie, for the Earl of Cromer, Evelyn Baring, had been governor general of the Sudan, Ethiopia’s neighbour, in the early years of the century. It was of course pure coincidence, for Cromer the man had no connection with Cromer the title. Nevertheless, it clinched matters. Selassie placed most of his wealth in the hands of Sir Charles Cromer II, who had inherited the bank in 1911.

When Ras Tafari became Emperor in 1930 as Haile Selassie, the hoard was growing at the rate of 100,000 ounces per year. In 1935, when the Italians invaded, gold production ceased. The invasion drove Selassie into exile in Bath. There he chose to live in austerity to underline his role as the plucky victim of Fascist aggression. But he still kept a sharp eye on his deposits.

After his triumphant return, with British help, in 1941, gold production resumed. The British exchange agreements for 1944 and 1945 show that some 8000 ounces per month were exported from Ethiopia. A good deal more left unofficially. One estimate places Ethiopia’s – or Selassie’s – gold exports for 1941–74 at 200,000 ounces per annum.

This hoard was increased in the 1940s by a currency reform that removed from circulation in Ethiopia several million of the local coins, Maria Theresa silver dollars (which in the 1970s were still accepted as legal currency in remote parts of Ethiopia and elsewhere in the Middle East). Most of the coins were transferred abroad and placed in the Emperor’s accounts. In 1975 Maria Theresa dollars had a market value of US$3.75 each.

In the 1950s, on the advice of young Charles Cromer himself, now heir to his aged father, Selassie’s wealth was diversified. Investments were made on Wall Street and in a number of American companies, a policy intensified by Charles Cromer III after he took over in 1955, at the age of thirty-one.

By the mid-1970s Selassie’s total wealth exceeded $2500 million.

Sir Charles knew that the fortune was secure, and that, with Selassie dead, his bank in particular, and those of his colleagues in Switzerland and New York, could continue to profit from the rising value of the gold indefinitely. The new government must know that there was no pressure that could be brought to bear to prise open the Emperor’s coffers.

Why then, the visit?

There came a gentle buzz over the intercom.

Cromer leaned over, flicked a switch and said gently: ‘Yes, Miss Yates?’

‘Mr Yufru is here to see you, Sir Charles.’

‘Excellent, excellent.’ Cromer always took care to ensure that a new visitor, forming his first impressions, heard a tone that was soft, cultured and with just a hint of flattery. ‘Please show Mr Yufru straight in.’

Six miles east of the City, in the suburban sprawl of east London, in one of a terrace of drab, two-up, two-down houses, two men sat at a table in a front room, the curtains drawn.

On the table stood an opened loaf of white sliced bread, some Cheddar, margarine, a jar of pickled onions and four cans of Guinness. One of the men was slim, jaunty, with a fizz of blond, curly hair and steady blue eyes. His name was Peter Halloran. He was wearing jeans, a pair of ancient track shoes and a denim jacket. In the corner stood his rucksack, into which was tucked an anorak. The other man, Frank Ridger, was older, with short, greying, curly hair, a bulbous nose and a hangdog mouth. He wore dungarees over a dirty check shirt.

They had been talking for an hour, since the surreptitious arrival of Halloran, who was now speaking. He dominated the conversation in a bantering Irish brogue, reciting the events of his life – the impatience at the poverty and dullness of village life in County Down, the decision to volunteer, the obsession with fitness, the love of danger, the successful application to join the SAS, anti-terrorist work in Aden in the mid-1960s and Oman (1971–4), and finally the return to Northern Ireland. It was all told with bravado and a surface glitter of which the older man was beginning to tire.

‘Jesus, Frank,’ the young man was saying, ‘the Irish frighten me to death sometimes. I was in Mulligan’s Bar in Dundalk, a quiet corner, me and a pint and a fellow named McHenry. I says to him there’s a job. That’s all I said. No details. I was getting to that, but not a bit of it – he didn’t ask who, or what, or how much, or how do I get away? You know what he said? “When do I get the gun?” That’s all he cared about. He didn’t even care which side – MI5, the Provos, the Officials, the Garda. I liked that.’

‘Well, Peter,’ said Ridger. He spoke slowly. ‘Did you do the job?’

‘We did. You should’ve seen the papers. “IRA seize half a million in bank raid.”’

‘But,’ said Ridger, draining his can, ‘I thought you said you were paid by the Brits?’

‘That’s right,’ said Halloran. He was enjoying playing the older man along, stoking his curiosity.

‘The British paid you to rob a British bank?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Were you back in favour or what?’

‘After what happened in Oman? No way.’

‘What did you do?’

‘There was a girl.’

‘Oh?’

‘How was I to know who she was? I was on my way home for a couple of months’ break. End of a contract. We had to get out or we’d have raped the camels. The lads, Mike Rourke among them, decided on a nice meal at the Sultan’s new hotel, the Al Falajh. She was – what? Nineteen. Old enough. I tell you, Frank – shall I tell you, my son?’

Ridger grinned.

Halloran first saw her in the entrance hall. Lovely place, the Al Falajh. Velvet all over the shop. Like walking into an upmarket strip club. She was saying goodnight to Daddy, a visiting businessman, Halloran assumed. ‘Go on then,’ Rourke had said, seeing the direction of his glance. He slipped into the lift behind her. She was wearing a blouse, short-sleeved and loose, so that as she stood facing away from him, raising her slim arm to push the lift button, he could see that she was wearing a silk bra, and that it was quite unnecessary for her to wear a bra at all. He felt she should know this, and at once appointed himself her fashion adviser.

‘Excuse me, miss, but I believe we have met.’ He paused as she turned, with a half smile, eager to be polite.

He saw a tiny puzzle cloud her brow.

‘Last night,’ he said.

She frowned. ‘I was…’

‘In a fantasy,’ he interrupted. It was corny, but it worked. By then she had been staring at him for seconds, and didn’t know how to cut him. She smiled. Her name was Amanda Price-Whyckham.

‘Eager as sin, she was,’ Halloran went on. A most receptive student, was Amanda P-W. The only thing she knew was la-di-da. Never had a bit of rough, let alone a bit of Irish rough. So when Halloran admired the view as the light poured through the hotel window, and through her skirt, and suggested that simplicity was the thing – perhaps the necklace off, then the stockings, she agreed she looked better and better the less she wore. ‘Until there she was, naked, and willing.’ Halloran finished. ‘My knees and elbows were raw by three in the morning.’

He smiled and took a swig of beer.

‘I don’t know how Daddy found out,’ Halloran continued after a pause. ‘Turned out he was a colonel on a visit for the MoD to see about some arms for the Omanis. You know, the famous Irish sheikhs – the O’Mahoneys?’

Ridger acknowledged the joke with a nod and a lugubrious smile.

‘So Daddy had me out of there. The SAS didn’t want me back, and I’d had enough of regular service. Used up half my salary to buy myself out. So it was back to pulling pints. Until the Brits approached me, unofficial like. Could I help discredit the Provos? Five hundred a month, in cash, for three months to see how it went. That was when my mind turned to banks. It was easy – home ground, see, because we used to plan raids with the regiment. Just plan mind. Now it was for real. I got a taste for it. Next I know, the Garda’s got me on file, and asks my controller in Belfast to have me arrested. He explains it nicely. They couldn’t exactly come clean. So they do the decent thing: put out a warrant for me, but warn me first. Decent! You help your fucking country, and they fuck you.’

‘You could tell.’

‘I wouldn’t survive to tell, Frank. As the bastard captain said, I’m OK if I lie low. In a year, two years, when the heat’s off, I can live again.’

‘I have the afternoon shift,’ said Frank, avoiding his gaze, and standing up. ‘I’ll be back about nine.’

‘We’ll have a few drinks.’

As the door closed, Halloran reached for another can of Guinness. He had no intention of waiting even a week, let alone a year, to live again.

Yufru was clearly at ease in the cold opulence of Sir Charles Cromer’s office. He was slim, with the aquiline good looks of many Ethiopians. He carried a grey cashmere overcoat, which he handed to Miss Yates, and wore a matching grey suit, tailored light-blue shirt and plain dark-blue tie.

Though Cromer never knew his background, Yufru had been living in exile since 1960. At that time he had been a major, a product of the elitist military academy at Harar. He had been one of a group of four officers who had determined to break the monolithic, self-seeking power of the monarchy and attempted to seize power while the Emperor was on a state visit to Brazil. The attempt was a disaster: the rebel officers, themselves arrogant and remote, never established how much support they would have, either within the army or outside it.

In the event, they had none. They took the entire cabinet hostage, shot most of them in an attempt to force the army into co-operation, and when they saw failure staring them in the face, scattered. Two killed themselves. Their corpses were strung up on a gallows in the centre of Addis. A third was captured and hanged. The fourth was Yufru. He drove over the border into Kenya, where he had been wise enough to bank his income, and surfaced a year later in London. Now, after a decade in business, mainly handling African art and supervising the investment of his profits, he had volunteered his services to the revolutionary government, seeking some revenge on the Imperial family and rightly guessing that his experience of the capitalist system might be of use.

He stood and looked round with admiration. Then, as Cromer invited him with a gesture to sit, he began to speak in suave tones that were the consequence of service with the British in 1941–5.

As Cromer knew, Ethiopia was a poor country. He, Yufru, had been lucky, of course, but the time had come for all of them to pull together. They faced the consequences of a terrible famine. The figures quoted in the West were not inaccurate – perhaps half a million would eventually die of starvation. Much, of course, was due to the inhumanity of the Emperor. He was remote, cut off in his palaces. The revolutionary government had attempted to reverse these disasters, but there was a limit imposed by a lack of funds and internal opposition.

‘These are difficult times politically,’ Yufru sighed. He was the ideal apologist for his thuggish masters. Cromer had met the type before – intelligent, educated, smooth, serving themselves by serving the hand that paid them. ‘We have enemies within who will soon be persuaded to see the necessity of change. We have foolish rebels in Eritrea who may seek to dismember our country. Somalia wishes to tear from us the Ogaden, an integral part of our country.

‘All this demands a number of extremely expensive operations. As you are no doubt aware, the Somalis are well equipped with Soviet arms. My government has not as yet found favour with the Soviets. If we are to be secure – and I suggest that it is in the interests of the West that the Horn of Africa remains stable – we need good, modern arms. The only possible source at present is the West. We do not wish to be a debtor nation. We would like to buy.

‘For that, to put matters bluntly, we need hard cash.’

Cromer nodded. He had guessed correctly.

‘The money for such purposes exists. It was stolen by Haile Selassie from our people and removed from the country, as you have good cause to know. I am sure you will respect the fact that the Emperor’s fortune is officially government property and that the people of Ethiopia, the originators of that wealth, should be considered the true heirs of the Emperor. They should receive the benefits of their labours.’

‘Administered, of course, by your government,’ Cromer put in.

‘Of course,’ Yufru replied easily, untouched by the banker’s irony. ‘They are the representatives of the people.’

Cromer was in his element. He knew his ground and he knew it to be rock-solid. He could afford to be magnanimous.

‘Mr Yufru,’ he began after a pause, ‘morally your arguments are impeccable. I understand the fervour with which your government is determined to right historic wrongs…’ – both of them were aware of what the fervour entailed: hundreds of corpses, ‘enemies of the revolution’, stinking on the streets of Addis – ‘and we would naturally be willing to help in any way. But insofar as the Emperor’s personal funds are concerned, there is really nothing we can do. Our instructions are clear and binding…’

‘I too know the instructions,’ Yufru broke in icily. ‘My father was with the Emperor in ’24. That is, in part, why I am here. You must have written instructions, signed by the Emperor, and sealed with the Imperial seal, on notepaper prepared by your bank, itself watermarked, again with the Imperial seal.’

Cromer acknowledged Yufru’s assertion with a slow nod.

‘Indeed, and those arrangements still stand. I have to tell you that the last such communication received by this bank was dated July 1974. Neither I nor my associates have received any further communication. We cannot take any action unilaterally. And, as the world knows, the Emperor is now dead, and it seems that the deposits must be frozen…’ – the banker spread his hands in a gesture of resigned sympathy – ‘in perpetuity.’

There was a long pause. Yufru clearly had something else to say. Cromer waited, still confident.

‘Sir Charles,’ Yufru said, more carefully now, ‘we have much work to do to regularize the Imperial records. The business of fifty years, you understand…It may be that the Emperor has left among his papers further instructions, perhaps written in the course of the revolution itself. And he was alive, you will remember, for a year after the revolution. It is conceivable that other papers relating to his finances will emerge. I take it that there would be no question that your bank and your associated banks would accept such instructions, if properly authenticated?’

The sly little bastard – he’s got something up his sleeve, thought Cromer. It may be…it is conceivable…if, if, if. There was no ‘if’ about it. Something solid lay behind the question.

To gain time he said: ‘I will have to check my own arrangements and those of my colleagues…there is something about outdated instructions which slips my mind. Anyway,’ he hastened on, ‘the instructions have always involved either new deposits or the transfer of funds and the buying of metals or stock. In what way would you have an interest in transmitting such information?’

Yufru replied, evenly: ‘We would like to be correct. We would merely like to be aware of your reactions if such papers were found and if we decided to pursue the matter.’

‘It seems an unlikely contingency, Mr Yufru. The Emperor has, after all, been dead six months.’

‘We are, of course, talking hypothetically, Sir Charles. We simply wish to be prepared.’ He rose, and removed a speck from his jacket. ‘Now, I must leave you to consider my question. May I thank you for your excellent coffee and your advice. Until next time, then.’

Puzzled, Sir Charles showed Yufru to the door. He was not a little apprehensive. There was something afoot. Yufru’s bosses were not noted for their philanthropy. They would have no interest in passing on instructions that might increase the Emperor’s funds.

It made no sense.

But by tonight, it damn well would.

‘No calls, Miss Yates,’ he said abruptly into the intercom. ‘And bring me the correspondence files for Lion…Yes, all of them. The whole damn filing cabinet.’

That evening, Sir Charles sat alone till late. A set of files lay on his desk. Against the wall stood the cabinet of files relating to Selassie. He again reviewed his thoughts on Yufru’s visit. He had to assume that there was something behind it. The only idea that made any sense was that there was some scheme to wrest Selassie’s money from the banks concerned. It couldn’t be done by halves. If they had access – with forged papers, say – then he had to assume that the whole lot was at risk.

And what a risk. He let his mind explore that possibility. Two thousand million dollars’ worth of gold from three countries for a start. If he were instructed, as it were by the Emperor himself, to sell every last ounce, it would be a severe blow to the liquidity of his own bank and those of his partners in Zurich and New York. With capital withdrawn, loans would have to be curtailed, profits lost. When and if it became known who was selling, reputations would suffer and rumours spread. Confidence would be lost. Even if there weren’t panic withdrawals, future deposits would be withheld. The effects would echo down the years and along the corridors of financial power, spreading chaos. With that much gold unloaded all at once, the price would tumble. And not only would he fail to realize the true market value, but he would become a pariah within Rothschild’s and in the international banking community. Cromer’s, renowned for its discretion, would be front-page news.

And that was just the gold. There would be the winding-up of a score of companies, the withdrawal of the cash balances, in sterling, Swiss francs and dollars.

Good God, he would be a liability. Eased out.

He poured himself a whisky and returned to his desk, forcing himself to consider the worst. In what circumstances might such a disaster occur?

What if Yufru produced documents bearing the Emperor’s signature, ordering his estate to be handed over to Mengistu’s bunch? With any luck they would be forgeries and easily spotted. On the other hand, they might be genuine, dating from before the Emperor’s death. But that was surely beyond the bounds of possibility. It would belie everything he knew about the man – ruthless, uncompromising, implacably opposed to any diminution of his authority.

But what if they had got at him, with drugs, or torture or solitary confinement? Now that was a possibility. Cromer would gamble his life on it that Selassie had signed nothing to prejudice his personal fortune before he was overthrown. But he might have done afterwards, if forced. He had after all been in confinement for about a year.

Now he had faced the implications, however, he saw that he could forestall the very possibility Yufru had mentioned. He checked one of the files before him again. Yes, no documents signed by the Emperor would be acceptable after such a delay. Anyone receiving written orders more than two weeks old had to check back on the current validity of those orders before acting upon them. The device was a sensible precaution in the days when couriers were less reliable than now, and communications less rapid. The action outlined in that particular clause had never been taken, and the clause never revoked. There it still stood, Cromer’s bastion against hypothetical catastrophe.

Cromer relaxed. But before long he began to feel resentful that he had wasted an evening on such a remote eventuality. He downed his whisky, turned off his lights, strolled over to the lift and descended to the basement, where the Daimler awaited him, his chauffeur dozing gently at the wheel. He was at his London home by midnight.

Friday 19 March

‘So you see, Mr Yufru, how my colleagues and I feel.’

Cromer had summoned Yufru for a further meeting earlier that morning.

‘After such a lapse of time and given the uncertainty of the political situation, we could not be certain that the documents would represent the Emperor’s lasting and final wishes. We would be required to seek additional confirmation, at source, before taking action. And the source, of course, is no longer with us.’

‘I see, Sir Charles. You would not, however, doubt the validity of the Emperor’s signature and seal?’

‘No, indeed. That we can authenticate.’

‘You would merely doubt the validity of his wishes, given the age of the documents?’

‘That is correct.’

‘I see. In that case, I am sure such a problem will never arise.’

Cromer nodded. The whole ridiculous, explosive scheme – if it had ever existed outside his own racing imagination – had been scotched. And apparently with no complications.

To hear Yufru talk, one would think the whole thing was indeed a mere hypothesis. Yufru remained affable, passed some complimentary comments about Cromer’s taste, and left, in relaxed mood.

The banker remained at his desk, deep in thought. He had no immediate appointments before lunch with a broker at 12.30, and he had the nagging feeling that he had missed something. There were surely only two possibilities. Mengistu’s bunch might have forged, or considered forging, documents. Or they might have the genuine article, however obtained. In either case, the date would precede Selassie’s death and they would now know that the date alone would automatically make the orders unacceptable. The fortune would remain for ever out of their reach.

Yufru had failed. Or had he? He didn’t seem like a man who had failed – not angry, or depressed, or fearful at reporting what might be a serious setback to the hopes of his masters. No: it was more as if he had merely ruled out just one course of action.

What other course remained open? What had he, Cromer, said that allowed the Ethiopians any freedom of action? The only positive statement he had made was that the orders, if they followed procedure, would be accepted as genuine documents, even if outdated.

Under what circumstances would the orders be accepted both as genuine and binding? If the date was recent, of course, but then…If the date was recent…in that case the Emperor would have to be…Dear God!

Cromer sat bolt upright, staring, unseeing, across the room. He had experienced what has been called the Eureka effect: a revelation based on the most tenuous evidence, but of such power that the conclusion is undeniable.

The Emperor must still be alive.

Cromer sat horrified at his own realization. He had no real doubts about his conclusion. It was the only theory that made sense out of Yufru’s approach. But he had to be certain that there was nothing to contradict it.

From the cabinet, against the wall, he slid out a file marked ‘Clippings – Death’. There, neatly tabbed into a loose-leaf folder, were a number of reports of Selassie’s death, announced on 28 August 1975 as having occurred the previous day, in his sleep, aged eighty-three.

According to the official government hand-out: ‘The Emperor complained of feeling unwell the previous night (26 August) but a doctor could not be obtained and a servant found him dead the next morning.’

Although he had been kept under close arrest in the compound in the Menelik Palace, there was no suggestion that he had been ailing. True, he had had a prostate operation two months before, but he had recovered well. One English doctor who treated him at that time, a professor from Queen Mary’s Hospital, London, was quoted as saying he had ‘never seen a patient of that age take the operation better’.

There had never been any further details. No family member was allowed to see the body. There was no post-mortem. The burial, supposedly on 29 August, was secret. There was no funeral service. The Emperor had, to all intents and purposes, simply vanished.

Not unnaturally, a number of people, in particular Selassie’s family, found the official account totally unacceptable. It reeked of duplicity. However disruptive the revolution, there were scores of doctors in Addis Ababa. Rumours began to circulate that Selassie had been smothered, murdered to ease the task of the revolution, for all the while he was known to be alive, large sections of the population would continue to regard him, even worship him, as the true ruler of the country. As The Times said when reporting the family’s opinion in June 1976: ‘The Emperor’s sudden death has always caused suspicion, if only because of the complete absence of medical or legal authority for the way he died.’

And so the matter rested. Until now. No wonder there had been no medical or legal authority for the way he died, mused Cromer. But the family had jumped to the wrong conclusion.

‘Sir Charles,’ it was Miss Yates’s voice on the intercom. ‘Will you be lunching with Sir Geoffrey after all?’

‘Ah, Miss Yates, thank you. Yes. Tell him I’m on my way. Be there in ten minutes.’

He stopped at the desk on his way out.

‘What appointments are there this afternoon?’ he asked.

‘You have a meeting with Mr Squires at two o’clock about the Shah’s most recent deposits. And of course the usual gold committee meeting at five.’

The Shah could wait. ‘Cancel Jeremy. I need the early afternoon clear.’

He glanced out of the window. It looked like rain. He took one of the two silk umbrellas from beside Valerie’s desk and left for lunch.