Читать книгу Nevernight - Jay Kristoff, Jay Kristoff - Страница 12

CHAPTER 2 MUSIC

ОглавлениеThe sky was crying.

Or so it had seemed to her. The little girl knew the water tumbling from the charcoal-coloured smudge above was called rain – she’d been barely ten years old, but she was old enough to know that. Yet she’d still fancied tears falling from that grey sugar-floss face. So cold compared to her own. No salt or sting inside them. But yes, the sky was certainly crying.

What else could it have done at a moment like this?

She’d stood on the Spine above the forum, gleaming gravebone at her feet, cold wind in her hair. People were gathered in the piazza below, all open mouths and closed fists. They’d seethed against the scaffold in the forum’s heart, and the girl wondered if they pushed it over, would the prisoners standing atop it be allowed to go home again?

O, wouldn’t that be wonderful?

She’d never seen so many people. Men and women of different shapes and sizes, children not much older than she. They wore ugly clothes and their howls had made her frightened, and she’d reached up and took her mother’s hand, squeezing tight.

Her mother didn’t seem to notice. Her eyes had been fixed on the scaffold, just like the rest. But Mother didn’t spit at the men standing before the nooses, didn’t throw rotten food or hiss ‘traitor’ through clenched teeth. The Dona Corvere had simply stood, black gown sodden with the sky’s tears, like a statue above a tomb not yet filled.

Not yet. But soon.

The girl had wanted to ask why her mother didn’t weep. She didn’t know what ‘traitor’ meant, and wanted to ask that, too. And yet, somehow she knew this was a place where words had no place. And so she’d stood in silence.

Watching instead.

Six men stood on the scaffold below. One in a hangman’s hood, black as truedark. Another in a priest’s gown, white as a dove’s feathers. The four others wore ropes at their wrists and rebellion in their eyes. But as the hooded man had slipped a noose around each neck, the girl saw the defiance draining from their cheeks along with the blood. In years to follow, she’d be told time and again how brave her father was. But looking down on him then, at the end of the row of four, she knew he was afraid.

Only a child of ten, and already she knew the colour of fear.

The priest had stepped forward, beating his staff on the boards. He had a beard like a hedgerow and shoulders like an ox, looking more like a brigand who’d murdered a holy man and stolen his clothes than a holy man himself. The three suns hanging on a chain about his throat tried to gleam, but the clouds in the crying sky told them no.

His voice was thick as toffee, sweet and dark. But it spoke of crimes against the Itreyan Republic. Of treachery and treason. The holy brigand called upon the Light to bear witness (she wondered if It had a choice), naming each man in time.

‘Senator Claudius Valente.’

‘Senator Marconius Albari.’

‘General Gaius Maxinius Antonius.’

‘Justicus Darius Corvere.’

Her father’s name, like the last note in the saddest song she’d ever heard. Tears welled in her eyes, blurring the world shapeless. How small and pale he’d looked down there in that howling sea. How alone. She remembered him as he’d been, not so long ago; tall and proud and O, so very strong. His gravebone armour white as wintersdeep, his cloak spilling like crimson rivers over his shoulders. His eyes, blue and bright, creased at the corners when he smiled.

Armour and cloak were gone now, replaced by rags of dirty hessian and bruises like fat, purpling berries all over his face. His right eye was swollen shut, his other fixed at his feet. She’d wanted him to look at her so badly. She wanted him to come home.

‘Traitor!’ the mob called. ‘Make him dance!’

The girl didn’t know what they’d meant. She could hear no music. fn1

The holy brigand had looked to the battlements, to the marrowborn and politicos gathered above. The entire Senate seemed to have turned out for the show, near a hundred men gathered in their purple-trimmed robes, staring down at the scaffold with pitiless eyes.

To the Senate’s right stood a cluster of men in white armour. Blood-red cloaks. Swords wreathed in rippling flame unsheathed in their hands. Luminatii, they were called, the girl knew that well. They’d been her father’s brothers-in-arms before the traitoring – such was, she’d presumed, what traitors did.

It’d all been so noisy.

In the midst of the senators stood a beautiful dark-haired man, with eyes of piercing black. He wore fine robes dyed with deepest purple – consul’s garb. And the girl who knew O, so little knew at least here was a man of station. Far above priests or soldiers or the mob bellowing for dancing when there was no tune. If he were to speak it, the crowd would let her father go. If he were to speak it, the Spine would shatter and the Ribs shiver into dust, and Aa, the God of Light himself, would close his three eyes and bring blessed dark to this awful parade.

The consul had stepped forward. The mob below fell silent. And as the beautiful man spoke, the girl squeezed her mother’s hand with the kind of hope only children know.

‘Here in the city of Godsgrave, in the Light of Aa the Everseeing and by unanimous word of the Itreyan Senate, I, Consul Julius Scaeva, proclaim these accused guilty of insurrection against our glorious Republic. There can be but one sentence for those who betray the citizenry of Itreya. One sentence for those who would once more shackle this great nation beneath the yoke of kings.’

Her breath had stilled.

Heart fluttered.

‘… Death.’

A roar. Washing over the girl like the rain. And she’d looked wide-eyed from the beautiful consul to the holy brigand to her mother – dearest Mother, make them stop – but Mother’s eyes were affixed on the man below. Only the tremor in her bottom lip betraying her agony. And the little girl could stand no more, and the scream roared up inside her and spilled over her lips

nonono

and the shadows all across the forum shivered at her fury. The black at every man’s feet, every maid and every child, the darkness cast by the light of the hidden suns, pale and thin though it was – make no mistake, O, gentlefriend. Those shadows trembled.

But not one person noticed. Not one person cared. fn2

The Dona Corvere’s eyes didn’t leave her husband as she took hold of the little girl, hugged her close. One arm across her breast. One hand at her neck. So tight the girl couldn’t move. Couldn’t turn. Couldn’t breathe.

You picture her now; a mother with her daughter’s face pressed to her skirts. The she-wolf with hackles raised, shielding her cub from the murder unfolding below. You’d be forgiven for imagining it so. Forgiven and mistaken. Because the dona held her daughter pinned looking outwards. Outwards so she could taste it all. Every morsel of this bitter meal. Every crumb.

The girl had watched as the hangman tested each noose, one by one by one. He’d limped to a lever at the scaffold’s edge and lifted his hood to spit. The girl glimpsed his face – yellow teeth grey stubble harelip gone. Something inside her screamed Don’t look, don’t look, and she’d closed her eyes. And her mother’s grip had tightened, her whisper sharp as razors.

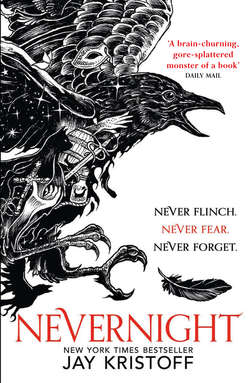

‘Never flinch,’ she breathed. ‘Never fear.’

The girl felt the words in her chest. In the deepest, darkest place, where the hope children breathe and adults mourn withered and fell away, floating like ashes on the wind.

And she’d opened her eyes.

He’d looked up then. Her father. Just a glance through the rain. She’d often wonder what he was thinking at that moment, in nevernights to come. But there were no words to cross that hissing veil. Only tears. Only the crying sky. And the hangman pulled his lever, and the floor fell away. And to her horror, she finally understood. Finally heard it.

Music.

The dirge of the jeering crowd. The whip-crack of taut rope. The guh-guh-guh of throttled men cut through with the applause of the holy brigand and the beautiful consul and the world gone wrong and rotten. And to the swell of that horrid tune, legs kicking, face purpling, her father had begun dancing.

Daddy …

‘Never flinch.’ A cold whisper in her ear. ‘Never fear. And never, ever forget.’

The girl nodded slowly.

Exhaled the hope inside.

And she’d watched her father die.

She stood on the deck of Trelene’s Beau, watching the city of Godsgrave growing smaller and smaller still. The capital’s bridges and cathedrals faded until only the Ribs remained; sixteen bone arches jutting hundreds of feet into the air. But as she watched, minutes melting into hours, even those titanic spires sank below the horizon’s lip and vanished in the haze.fn3

Her hands were pressed to salt-bleached railing, dry blood crusted under her nails. A gravebone stiletto at her belt, a hangman’s teeth in her purse. Dark eyes reflecting the moody red sun overhead, the echo of its smaller, bluer sibling still rippling in western skies.

The cat who was shadows was there with her. Puddled in the dark at her feet while it wasn’t needed. Cooler there, you see. A clever fellow might’ve noticed the girl’s shadow was a touch darker than others. A clever fellow might’ve noticed it was dark enough for two.

Fortunately, clever fellows were in short supply aboard the Beau.

She wasn’t a pretty thing. O, the tales you’ve heard about the assassin who destroyed the Itreyan Republic no doubt described her beauty as otherworldly; all milk-white skin and slender curves and bow-shaped lips. And she was possessed of these qualities, true, but the composition seemed … a little off. ‘Milk-white’ is just pretty talk for ‘pasty,’ after all. ‘Slender’ is a poet’s way of saying ‘starved.’

Her skin was pale and her cheeks hollow, lending her a hungry, wasted look. Crow-black hair reached to her ribs, save for a self-inflicted and crooked fringe. Her lips and the flesh beneath her eyes seemed perpetually bruised, and her nose had been broken at least once.

If her face were a puzzle, most would put it back in the box, unfinished.

Moreover, she was short. Stick-thin. Barely enough arse for her britches to cling to. Not a beauty that lovers would die for, armies would march for, heroes might slay a god or daemon for. All in contrast to what you’ve been told by your poets, I’m sure. But she wasn’t without her charm, gentlefriends. And all your poets are full of shit.

Trelene’s Beau was a two-mast brigantine crewed by mariners from the isles of Dweym, their throats adorned with draketooth necklaces in homage to their goddess, Trelene.fn4 Conquered by the Itreyan Republic a century previous, the Dweymeri were dark of skin, most standing head and shoulders above the average Itreyan. Legend had it they were descended from the daughters of giants who lay with silver-tongued men, but the logistics of this legend fail under any real scrutiny.fn5 Simply said, as a people, they were big as bulls and hard as coffin nails, and tendencies to adorn their faces with leviathan ink tattoos didn’t help with first impressions.

Fearsome appearances aside, Dweymeri treat their passengers less as guests and more as sacred charges. And so, despite the presence of a sixteen-year-old girl aboard – travelling alone and armed with only a sliver of sharpened gravebone – making trouble for her couldn’t have been further from most of the sailors’ minds. Sadly, there were several recruits aboard the Beau not born of Dweym. And to one among them, this lonely girl seemed worthy of sport.

It’s truth to say in all save solitude – and in some sad cases, even then – you can always count on the company of fools.

He was a rakish sort. A smooth-chested Itreyan buck with a smile handsome enough to earn a few bedpost notches, his felt cap adorned with a peacock’s quill. It’d be seven weeks before the Beau set ashore in Ashkah, and for some, seven weeks is a long wait with only a hand for company. And so he leaned against the railing beside her and offered a feather-down smile.

‘You’re a pretty thing,’ he said.fn6

She glanced long enough to measure, then turned those coal-black eyes back to the sea.

‘I’ve no business with you, sir.’

‘O, come now, don’t be like that, pretty. I’m only being friendly.’

‘I’ve friends enough, thank you, sir. Please leave me be.’

‘You look friendless enough to me, lass.’

He reached out one too-gentle hand, brushed a hair from her cheek. She turned, stepped closer with the smile that, in truth, was her prettiest part. And as she spoke, she drew her stiletto and pressed it against the source of most men’s woes, her smile widening along with his eyes.

‘Lay hand upon me again, sir, and I’ll feed your jewels to the fucking drakes.’

The peacock squeaked as she pressed harder at the heart of his problems – no doubt a smaller problem than it’d been a moment before. Paling, he stepped back before any of his fellows witnessed his indiscretion. And giving his very best bow, he slunk off to convince himself his hand might be better company after all.

The girl turned back to the sea. Slipped the dagger back into her belt.

Not without her charms, as I said.

Seeking no more attention, she kept herself mostly to herself, emerging only at mealtimes or to take some air in the still of nevernight. Hammock-bound in her cabin, studying the tomes Old Mercurio had given her, she was content enough. Her eyes strained with the Ashkahi script, but the cat who was shadows helped her with the most difficult passages – curled within the folds of her hair and watching over her shoulder as she studied Hypaciah’s Arkemical Truths and a dust-dry copy of Plienes’s Theories of the Maw.fn7

She was bent over Theories now, smooth brow marred by a scowl.

‘… try again …’ the cat whispered.

The girl rubbed her temples, wincing. ‘It’s giving me a headache.’

‘… o, poor girl, shall i kiss it better …’

‘This is children’s lore. Any knee-high tadpole gets taught this.’

‘… it was not written with itreyan audiences in mind …’

The girl turned back to the spidery script. Clearing her throat, she read aloud:

‘The skies above the Itreyan Republic are illuminated by three suns – commonly believed to be the eyes of Aa, the God of Light. It is no coincidence Aa is often referred to as the Everseeing by the unwashed.’

She raised an eyebrow, glanced at the shadowcat. ‘I wash plenty.’

‘… plienes was an elitist …’

‘You mean a tosser.’

‘… continue …’

A sigh. ‘The largest of the three suns is a furious red globe called Saan. The Seer. Shuffling across the heavens like a brigand with nothing better to do, Saan hangs in the skies for near one hundred weeks at a time. The second sun is named Saai. The Knower. A smallish blue-faced fellow, rising and setting quicker than its brother—’

‘… sibling …’ the cat corrected. ‘… old ashkahi does not gender nouns …’

‘… quicker than its sibling, it visits for perhaps fourteen weeks at a stretch, near twice that spent beyond the horizon. The third sun is Shiih. The Watcher. A dim yellow giant, Shiih takes almost as long as Saan in its wanderings across the sky.’

‘… very good …’

‘Between the three suns’ plodding travells, Itreyan citizens know actual nighttime – which they call truedark – for only a brief spell every two and a half years. For all other eves – all the eves Itreyan citizens long for a moment of darkness in which to drink with their comrades, make love to their sweethearts …’

The girl paused.

‘What does oshk mean? Mercurio never taught me that word.’

‘… unsurprising …’

‘It’s something to do with sex, then.’

The cat shifted across to her other shoulder without disturbing a single lock of hair.

‘… it means “to make love where there is no love” …’

‘Right.’ The girl nodded. ‘… make love to their sweethearts, fuck their whores, or any other combination thereof – they must endure the constant light of so-called nevernight, lit by one or more of Aa’s eyes in the heavens.

‘Almost three years at a stretch, sometimes, without a drop of real darkness.’

The girl closed the book with a thump.

‘… excellent …’

‘My head is splitting.’

‘… ashkahi script was not meant for weaker minds …’

‘Well, thank you very much.’

‘… that is not what i meant …’

‘No doubt.’ She stood and stretched, rubbed her eyes. ‘Let’s take some air.’

‘… you know i do not breathe …’

‘I’ll breathe. You watch.’

‘… as it please you …’

The pair stole up onto the deck. Her footsteps were less than whispers, and the cat’s, nothing at all. The roaring winds that marked the turn to nevernight waited above – Saai’s blue memory fading slowly on the horizon, leaving only Saan to cast its sullen red glow.

The Beau’s deck was almost empty. A huge, crook-faced helmsman stood at the wheel, two lookouts in the crow’s nests, a cabin boy (still almost a foot taller than she) snoozing on his mop handle and dreaming of his maid’s arms. The ship was fifteen turnings into the Sea of Swords, the snaggletooth coastline of Liis to the south. The girl could see another ship in the distance, blurred in Saan’s light. A heavy dreadnought, flying the triple suns of the Itreyan navy, cutting the waves like a gravebone dagger through an old nooseman’s throat.

The bloody ending she’d gifted the hangman hung heavy in her chest. Heavier than the memory of the sweetboy’s smooth hardness, the sweat he’d left drying on her skin. Though this sapling would bloom into a killer whom other killers rightly feared, right now she was a maid fresh-plucked, and memories of the hangman’s expression as she cut his throat left her … conflicted. It’s quite a thing, to watch a person slip from the potential of life into the finality of death. It’s another thing entirely to be the one who pushed. And for all Mercurio’s teachings, she was still a sixteen-year-old girl who’d just committed her first act of murder.

Her first premeditated act, at any rate.

‘Hello, pretty.’

The voice pulled her from her reverie, and she cursed herself for a novice. What had Mercurio taught her? Never leave your back to the room. And though she might’ve protested her recent bloodlettings constituted worthy distraction, or that a ship’s deck wasn’t even a room, she could almost hear the willow switch the old assassin would have raised in answer.

‘Twice up the stairs!’ he’d have barked. ‘There and back again!’

She turned and saw the young sailor with his peacock-feather cap and his bed-notch smile. Beside him stood another man, broad as bridges, muscles stretching his shirtsleeves like walnuts stuffed into poorly tailored bags. An Itreyan also by the look, tanned and blue-eyed, the dull gleam of Godsgrave streets etched in his gaze.

‘I was hoping I’d see you again,’ Peacock said.

‘The ship isn’t large enough for me to hope otherwise, sir.’

‘Sir, is it? Last we spoke, you voiced threat of removing parts most treasured and feeding them to the fish.’

She was looking at the boy. Watching the stuffed walnut bag from beneath her lashes.

‘No threat, sir.’

‘Just boasting, then? Thin talk for which apology is owed, I’d wager.’

‘And you’d accept apology, sir?’

‘Belowdecks, doubtless.’

Her shadow rippled, like millpond water as rain kissed the surface. But the peacock was intent on his indignity, and the walnut thug on the lovely hurtings he might bestow if given a few minutes with her in a cabin without windows.

‘I only need to scream, you realise,’ she said.

‘And how much scream could you give voice,’ Peacock smiled, ‘before we tossed your scrawny arse over the side?’

She glanced to the pilot’s deck. To the crow’s nests. A tumble into the ocean would be a death sentence – even if the Beau came about, she could swim only a trifle better than its anchor, and the Sea of Swords teemed with drakes like a dockside sweetboy crawled with crabs.

‘Not much of a scream at all,’ she agreed.

‘… pardon me, gentlefriends …’

The thugs started at the voice – they’d heard nobody approach. Both turned, Peacock puffing up and scowling to hide his sudden fright. And there on the deck behind them, they saw the cat made of shadows, licking at its paw.

It was thin as old vellum. A shape cut from a ribbon of darkness, not quite solid enough that they couldn’t see the deck behind it. Its voice was the murmur of satin sheets on cold skin.

‘… i fear you picked the wrong girl to dance with …’ it said.

A chill stole over them, whisper-light and shivering. Movement drew Peacock’s eyes to the deck, and he realised with growing horror that the girl’s shadow was much larger than it should, or indeed could have been. And worse, it was moving.

Peacock’s mouth opened as she introduced her boot to his partner’s groin, kicking him hard enough to cripple his unborn children. She seized the walnut thug’s arm as he doubled up, flipping him over the railing and into the sea. Peacock cursed as she moved behind him, but he found he couldn’t shift footing to match her – as if his boots were glued in the girl’s shadow on the deck. She kicked him hard in his backside and he toppled face-first into the rails, spreading his nose across his cheeks like bloodberry jam. The girl spun him, knife to throat, pushing him against the railing with his spine cruelly bent.

‘I beg pardon, miss,’ he gasped. ‘Aa’s truth, I meant no offence.’

‘What is your name, sir?’

‘Maxinius,’ he whispered. ‘Maxinius, if it please you.’

‘Do you know what I am, Maxinius-If-It-Please-You?’

‘… D-da …’

His voice trembled. His gaze flickering to shadows shifting at her feet.

‘Darkin.’

In his next breath, Peacock saw his little life stacked before his eyes. All the wrongs and the rights. All the failures and triumphs and in-betweens. The girl felt a familiar shape at her shoulder – a flicker of sadness. The cat who was not a cat, perched now on her clavicle, just as it had perched on the hangman’s bedhead as she delivered him to the Maw. And though it had no eyes, she could tell it watched the lifetime in Peacock’s pupils, enraptured like a child before a puppet show.

Now understand; she could have spared this boy. And your narrator could just as easily lie to you at this juncture – some charlatan’s ruse to cast our girl in a sympathetic light.fn8 But the truth is, gentlefriends, she didn’t spare him. Yet, perhaps you’ll take solace in the fact that at least she paused. Not to gloat. Not to savour.

To pray.

‘Hear me, Niah,’ she whispered. ‘Hear me, Mother. This flesh your feast. This blood your wine. This life, this end, my gift to you. Hold him close.’

A gentle shove, sending him over into the gnashing swell. As the peacock’s feather sank beneath the water, she began shouting over the roaring winds, loud as devils in the Maw. Man overboard! She screamed. Man overboard! And soon the bells were all a-ringing. But by the time the Beau turned about, no sign of Peacock or the walnut bag could be found among the waves.

And as simple as that, our girl’s tally of endings had multiplied threefold.

Pebbles to avalanches.

The Beau’s captain was a Dweymeri named Wolfeater, seven feet tall with dark locks knotted by salt. The good captain was understandably put out by his crewmen’s early disembarkation, and keen on hows and whys. But when questioned in his cabin, the small, pale girl who sounded the alarm only mumbled of a struggle between the Itreyans, ending in a tumble of knuckles and curses sending both overboard to sailor’s graves. The odds that two seadogs – even Itreyan fools – had tussled themselves into the drink were slim. But thinner still were the chances this girlchild had gifted both to Trelene all by her lonesome.

The captain towered over her; this waif in grey and white, wreathed in the scent of burned cloves. He knew neither who she was nor why she journeyed to Ashkah. But as he propped a drakebone pipe on his lips and struck a flintbox to light his tar, he found himself glancing at the deck. At the shadow coiled about this strange girl’s feet.

‘Best be keeping yourself to yourself ’til trip’s end, lass.’ He exhaled into the gloom between them. ‘I’ll have meals sent to your room.’

The girl looked him over, eyes black as the Maw. She glanced down at her shadow, dark enough for two. And she agreed with the Wolfeater’s assessment, her smile sweet as honeydew.

Captains are usually clever fellows, after all.