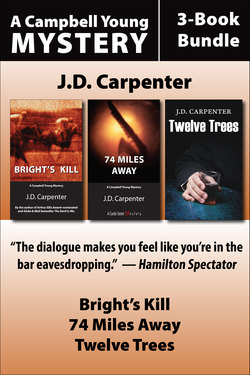

Читать книгу Campbell Young Mysteries 3-Book Bundle - J.D. Carpenter - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Monday, June 5

ОглавлениеYoung had just sat down in his cubicle and was peeling the lid off his coffee cup when Wheeler arrived.

“Morning,” he said.

“Morning.”

He followed her down the hall. “How was your weekend?”

“Not bad, how was yours?” She opened the door to the half-fridge that stood beside the coffee maker and placed her lunchbox on the top shelf. “Is this your banana in here?” she asked. “It’s all black.”

“No, it’s not mine. Me and Trick—”

“How about this bagel? The one with the mould.”

“Nope, not guilty. Me and Trick lost about two bills each at the track.” He wasn’t looking at her. He blew into his coffee. “Listen, sorry about Saturday night. That phone call. Did I say anything stupid?”

She took off her HOYAS ballcap and shook out her short blonde hair. “I wish people would be a bit more responsible. It’s like living with animals.”

“Wheeler—”

“Yes, you said plenty.”

“Like what?”

“That’s for me to know and you to find out.”

“Oh, come on, that’s not fair.” But he knew he wasn’t going to make any headway. “How about you? What did you do this weekend?”

“I visited my mother Saturday. We went to a craft show.” She looked tired, and she was using her brown eye on Young.

“Yeah, and what about yesterday?”

“I worked.”

“You worked? You had both days off.”

“Staff Inspector Bateman okayed me to do some overtime, so I worked four hours in the afternoon.” She sat down at her desk.

“You should let me know when you decide to do something like that. I could have—”

“I wanted you to enjoy yourself. Staff Inspector Bateman told me you worked Saturday.”

“Yeah, so?”

“So you worked Saturday, I worked Sunday. You saw Trick, right?”

“Yeah, I told you, we lost two bills each.”

“And Debi?”

“Yeah, she was there. What the fuck—”

“That’s good. Do you want to know what I’ve got on the Shorty Rogers case?”

Young arched his eyebrows. “Yeah, of course.” He sat down in the chair opposite Wheeler’s desk.

“It’s getting pretty interesting.”

“What do you mean?”

“Among other things, you wanted me to find out what I could about Shorty Rogers’ uncle, right?”

“Right.”

“Well, once I found out that Morley Rogers was Shorty’s only living relative, I drove up there—”

“Up where?”

“Up to his farm. In the Caledon Hills. It’s not really a farm anymore, he’s sold most of the land. It’s really just a farmhouse, and a falling-down one at that.”

“So what happened?”

“I interviewed the housekeeper.”

Young shifted in his chair. “Did you talk to the old man?”

“I tried. I told the housekeeper I was part of the murder investigation and that I needed to talk to Shorty’s uncle, but she wouldn’t let me. She said that even though Mr. Rogers had little use for his nephew, he was too upset about what had happened to see anyone. She said he was in seclusion, praying.”

“So you talked to her instead.”

Wheeler nodded. “She told me all sorts of stuff. But the really interesting thing she told me was what happened a month ago. It seems Mr. Rogers held a special sort of top secret meeting at his farmhouse to discuss the possible sale of his property, and the list of people who attended—by invitation only, I should point out—is pretty interesting.”

“Interesting how?”

“Well, the lottery winner, Doug Buckley, was there, and Mahmoud Khan, the Internet King, he was there, too.” Wheeler took her notebook from her jacket pocket and flipped several pages into it. “And a man named Richard Ludlow, who’s like a huge land developer and president of the King County Golf and Country Club. And Summer Caldwell, who’s some sort of important socialite. I wrote down here that she’s a horticulturalist.”

“That’s flowers, right?”

“Right. Also, a man named Stirling Smith-Gower was there. He sounds like a bit of a nut. He fights for animal rights, that kind of thing. By profession, he’s an ornithologist.”

“Birds,” Young said.

“And the housekeeper herself was there. Her name’s Myrtle Sweet. And Mr. Rogers’ bodyguards.”

“Bodyguards?”

“Yeah, apparently he’s got two bodyguards.”

Young nodded. “Okay. Anybody else there?”

“Yeah, Shorty himself was there.”

“No shit. When was this meeting?”

Wheeler referred to her notes again. “May 17. Two weeks before he was murdered.”

“So tell me about the meeting.”

“I can do better than that.” Wheeler lifted her briefcase onto her desk and opened it. She held up a VHS cassette. “When I was about to leave, Miss Sweet asked me to wait. I stood by the door while she went upstairs. When she came back, she was carrying this. She said Mr. Rogers wants us to have a look at it. It’s a videotape of the meeting.”

After the blue screen was replaced first by snow and then by diagonal black bars that rose and fell for several seconds, the face, in close-up, of an old man appeared. “Are we ready, Kevin?” the old man asked in a reedy voice. Another voice, off-camera, said, “Ready, sir.” The old man was wearing a charcoal gray suit coat, a white shirt frayed at the collar tips and yellow at the neck, and a thin black tie dusty at the knot. He was hunched at the shoulders and had difficulty keeping his head up. The camera backed off shakily to reveal that he was leaning heavily on the handlebars of a walker. “All right then, I think we’ll begin,” he said. “Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Bright’s Kill. Glad all of you could make it. I hope you’re comfortable. Some of those card table chairs you’re sitting on are a bit wonky, but I’m afraid we’re a bit challenged—as the bureaucrats like to say these days—in the furniture department. And I apologize for the humidity, but I thought the solarium would provide a picturesque setting for this little shindig of mine. As you can see, we’re surrounded by a paradise of lilies and orchids and various ferns and other tropical plants. This room is my pride and joy, ladies and gentlemen, my only extravagance, and the rock garden to your left with its statue of a little boy tinkling, and the tiled pool below him, and the Chinese carp which are resident there, are but a sampling of the added touches I have allowed myself.”

A scraping of chairs was audible as members of the audience moved in their seats to better see the solarium’s features. The camera, however, remained on the old man as he said, “My name is Morley Rogers, which should come as no surprise to any of you, being as you’re all here for one reason and one reason only: to separate me from my property. Some of you, I dare say, think I’m nothing more than a feeble old hermit taking his own sweet time to die, that I’m nothing more than a Bible-beating Baptist and an old miser, that something perverse in my nature makes me hang on to these twelve acres you crave so desperately.” He raised a hand to his mouth and suppressed a cough. “But I forget my manners. While some of you may know me, I doubt that any among you has made the acquaintance of this delightful creature.” He fluttered a trembling liver-spotted hand in the direction of a woman standing a few feet behind him. The camera swivelled and zoomed in slightly on a handsome black-haired woman dressed in a navy jacket, white blouse, and red necktie. “My assistant, ladies and gentlemen, Miss Myrtle Sweet.” The old man coughed into his fist. “Miss Sweet is more than just my assistant. She is my nurse, my secretary, my cook, my housekeeper, my helpmeet, my friend, my companion. If I weren’t a God-fearing man, I’d add rod and staff, because in her gentle ministrations she comforts me. But now to the business at hand.” More scraping of chairs could be heard.

“My farm, or what’s left of it, is named after a Dutchman, Jacob Bright, who settled here in the 1830s. It’s been in my family a hundred twenty years. According to the deeds, all of which I have in my possession, Bright used to be spelled B-r-i-e-t or B-r-e-e-t, and may have been pronounced Breet. Nobody knows for sure because the signature on the deed of 1834 is smudged, and the township records for that period carry both spellings. Kill, in case you are unaware, is Dutch for creek or stream, and the creek or stream that bears Jacob Bright’s name, and that I once swam in and watered the Clydesdales in and caught perch and sunfish out of, is now part of that accursed golf course next door. All I have left is the house and twelve acres and the grove of black walnut trees you drove past on your way in. My grandfather Anson Red Rogers planted those trees. They’re ninety-seven years old, almost as old as I am!” As his audience laughed politely, he stopped, turned his head to the side, and coughed again. “But getting down to business,” he said, “I’ve been hearing that a number of different parties are covetous of my property. Well, I say beware the tenth commandment: ‘Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbour’s.’ Being as how I don’t have a wife or an ox or an ass, and being as how my employees are more like family than servants, it’s the part about the house that troubles me—the house and the field-land that goes with it. And lest you take me too lightly, ladies and gentlemen, be advised that I am on my guard against schemers and blasphemers, fornicators and flim-flam-mers.” He stopped again, wracked by a fit of coughing. Myrtle Sweet stepped forward with a glass of water, but even as he sipped at it, his eyes surveyed his audience.

When he had recovered sufficiently to continue, he said, “Eric, would you fetch me a tissue, please.” He cleared his throat. “You might be curious, ladies and gentlemen, about the presence in your midst of two dusky strangers. Their names are Kevin and Eric Favors, though which is which is a puzzle to anyone unfamiliar with them. They are identical in appearance, but in every other way they are as different as night and day. Kevin, who is manning the camera, is a devout Christian, like myself, who reads his Bible every night and who believes in turning the other cheek. He is a diplomat and a negotiator. He is a gentleman, God bless, but he is loyal to me and would, if necessary, use his considerable strength to protect me. Eric, on the other hand, couldn’t give two hoots about the Bible. He would just as soon smite you as smile at you. He has the instincts of a beast of the fields, but he knows who feeds him and shelters him, and so he is loyal to me just as his brother is. The distinction between them is plain: where Kevin would take no pleasure in hurting you, Eric would. I do not speak of Eric this way because he’s off finding me something to wipe my nose with; even if he were here, he wouldn’t object. He’s devoted to me, as is Kevin. Together, they are my muscle. They may exhibit a calm and quiet demeanor, but don’t be fooled: they’re as deadly as vipers. If murderous thoughts lurk at the back of your mind, if any among you would steal my purse, be forewarned: I am prepared; I am protected. Ah, here we are.”

A black hand proffered a yellow Kleenex box. “Thank you, Eric.” The old man blew his nose vigorously.

“But beg pardon, I’ve been yammering away like an old woman up here. If no one objects, I’ll hear each of you out as you present your arguments. I am curious as to the various purposes to which my small empire might be put. I know that among you we have a real estate developer, an ornithologist, a horticulturalist, and a businessman who works with the Internet. I know what the first three do, but I’m not so sure about the Internet; is it some new-fangled kind of fishing tackle?”

More laughter could be heard.

“Mr. Richard Ludlow,” the old man said, “if you’re with us this evening, please approach the podium.” As his eyes followed a progress in front of him, he said, “I hope you will not be discomfited by the presence of the camera, ladies and gentlemen, but for my own peace of mind I am recording the events of the evening. Consider it a form of insurance. If I appear not to trust you, it is because, quite frankly, I don’t. You would rob me in my sleep if you could. Should anything untoward befall me in the future, this film will at least provide the police with something to go on.”

The camera zoomed out to accommodate the arrival of a middle-aged man—tall, ruddy-cheeked, silver-haired, immaculately dressed.

“According to my information, sir,” Morley Rogers said, “you are a real estate developer and a man of vast commercial experience. I hope you don’t think me presumptuous if I ask you to go first, to set an example, so to speak, with respect to briefs and how they are presented. Please sir, say your piece.”

Ludlow’s face was tanned and handsome, his manner assured. “Mr. Rogers, ladies and gentlemen,” he began, “my proposal is simple: I want to convert these twelve acres into a condominium complex adjacent to the fourteenth tee of the golf course. At present, the land is unused, indeed unusable. It is marshy and buggy; it contains nothing but bulrushes and blackbirds. If my plan is accepted, hundreds of truckloads of clean fill will convert this area into a thriving micro-community of upwards of two hundred people. Think, Mr. Rogers, of the economic boost such a project would provide. Not to mention the humanitarian angle. There are a great many people living in congested, polluted areas of Toronto who would give their eye teeth to live out here in the fresh air and the countryside—”

“Point of clarification!” a voice from the audience shouted. The camera rotated to reveal a row of people seated in front of a jungle scene. A pale, balding man was standing up in front of his chair. He was dressed in paint-stained jeans and an old cardigan and clutched a fuming pipe in one hand. “Mr. Rogers, your twelve acres are neither unused nor unusable,” he said in an unmistakably British accent. “They are the natural habitat of a variety of endangered birds. It is our duty to protect our avian population, a threatened population—”

“Oh please,” Ludlow could be heard to say, “spare us the sermon.”

“—that includes the King Rail, the Least Bittern, the Loggerhead Shrike, Kirtland’s Warbler, the Hooded Warbler, and the Prothonotary Warbler. Corporate greed has already eliminated most of the wetlands in our vicinity, and—”

A banging sound was heard, and the focus of the camera returned to the front of the solarium where Morley Rogers was banging a garden trowel against one of the handlebars of his walker. “Sit down, both of you!” he shouted hoarsely. “You’re both out of order. Mr. Ludlow, you use the word sermon as if it were an obscenity, and you—Mr. Smith-Gower, I presume—you call yourself a naturalist, an environmentalist, an ornithologist, yet you smoke that filthy pipe in a room full of orchids! Sit down, both of you!”

Ludlow opened his mouth to speak, then shook his head, smiled ruefully at the camera, and disappeared from view.

“Next!” Morley Rogers demanded.

A chair could be heard scraping, then the clip-clop-ping of high-heeled shoes.

The carefully coiffed woman who appeared on screen placed a pair of decorator bifocals on her nose, cleared her throat, and said, “My reason for being here is just as simple as Mr. Ludlow’s and just as environmental as Mr. Smith-Gower’s: Mr. Rogers, I think your land should be converted into a park. But not just any park: a flower park!” The woman’s voice quivered with conviction. “The public could come and stroll along the crushed granite footpaths and observe the flower competitions.” She spread her arms: bracelets jingled and rings sparkled. “Can’t you just see it? Banks and banks of tulips and geraniums, and that’s not all: duck ponds and gazebos and a little mill with a waterwheel and footbridges and—”

“Idle rich!” Smith-Gower’s voice declared.

Morley Rogers beat the trowel against his walker. “Mrs. Caldwell,” he said in his thin voice, the camera once again on him, his small head wobbling back and forth, “some of these people may not know that you are the perennial runner-up in Caledon Township’s Beautiful Garden Competition, and the fact is you’re just plumb jealous of the perennial winner, which happens to be me, God bless! Ladies and gentlemen, Mrs. Caldwell figures if she can dispossess me of my land and plunk me down to rot in some old folks home, then she might win! You know what I say to that? I say horse apples! Next!”

Summer Caldwell huffed her way out of view and was replaced moments later by a tall, thin East Indian man, who stood quietly until the clip-clopping stopped. Dressed in a light gray suit and royal blue tie, the man cast his piercing black eyes across his listeners and said in a richly accented voice, “Thank you, Mr. Rogers. My name is Mahmoud Khan, and like everyone else here, I have my own agenda. I have my own reasons for wanting your land. As you may know, I am the owner of Dot Com Acres, the farm next door, formerly known as Cedar Creek Stud Farm. That’s right, I am the businessman of the Internet. The Internet, Mr. Rogers,” and he inclined his head to his host, “in case you are truly unaware and were not just making a joke with us, is a form of global communication and information access. People use it on their computers. My success as a businessman did not come without struggle; nevertheless, it is, as you like to say in this fine country, a dream come true. However, my friend, I have another dream as well. I am embarking on an ambitious program that involves the breeding of thor-oughbred racehorses. Foolishly, perhaps, I sold much of Cedar Creek soon after purchasing it, and now find myself in need of additional land to accommodate the broodmare band I am putting together. Your twelve acres would give me room for a larger barn and several pasture fields. It may interest you to know as well, sir, that two of my horses are currently in training with your nephew.”

“Nephew?” Morley could be heard to bluster. “What nephew? I have no nephew!”

Khan was taken aback. “I beg your pardon, sir. I must be mistaken. You have the same last name, and I was led to understand that you were related. In any case, I want you to know that I am prepared to match and exceed any offer you receive from these other worthy candidates. I thank you for your time.”

After Mahmoud Khan bowed and returned to his chair and Morley Rogers was once again on camera, he said, “This accursed housing project going up across the road here, it used to be part of Cedar Creek, am I right?”

Khan’s voice could be heard to say, “Yes, sir, but at the time of the sale I had no idea what was to be done with the land.”

Morley Rogers shifted his gaze. His eyes were like two arrows. “You the developer, Mr. Ludlow?”

Ludlow cleared his throat. “Well, in a manner of speaking—”

“I thought so. Next!”

After a few moments of shuffling, Doug Buckley appeared before the camera. He was wearing a salmon leisure suit over a lemon-coloured shirt whose collar wings extended four inches.

“Happy to introduce myself, Mr. Rogers,” Doug said, nodding to his host. “Buckley’s the name. I’m new to these parts, as John Wayne might say, but I hope to stay put. I’d be pleased and honoured to buy your land, just to put down roots in this fine community”—he gave a chuckle—“but I’ll be darned if I know what to do with it. But I’ll tell you one thing—I can afford it! Money is the least of my problems.” He laughed again. “Happen to own a racehorse myself, Mr. Rogers. Shorty trains it—I know you’re just pulling our leg about not having a nephew, he’s sitting right over there! Well, pleased to make your acquaintance.” He laughed again and disappeared.

The camera moved to Morley Rogers, who was glowering. “‘For ye suffer fools gladly, seeing ye yourselves are wise.’ Second Corinthians, eleven, nineteen. Next!”

More shuffling until the top of a feed cap appeared on screen. The camera lowered to reveal a sweating red face, in profile. “Uncle Morley,” the man, who was wearing a Toronto Maple Leafs hockey sweater, began, “I know we ain’t seen each other in a long time—”

Morley Rogers, off-camera, said, “I don’t know you.”

“It’s Delbert, Uncle Morley. Your nephew. Shorty, as some call me. I was hoping you might ... well, maybe this ain’t the right place for me to be asking you this ...”

“Ask me what?”

Shorty Rogers removed his feed cap to reveal a bald and glistening dome. “I’m a little down on my luck, Uncle Morley, and I was hoping you might—”

“Might what, you ingrate?” Morley Rogers’ face appeared, also in profile, inches from his nephew’s. “Might advance you a boatload of money? Might finance your next failure? You’ve got some nerve. I haven’t seen you in years, not since your sainted father passed away, God bless, and here you are, you show up out of the blue looking for handouts. Well, forget it. Take a seat. Or better yet, crawl back to whatever liquor house you crawled out of.”

Squeezing his feed cap, Shorty said, “But all I need is a few thousand—”

“Out of my sight, damn you! Back to your saloons and back alleys, your brothels, your Jezebels!”

“But Uncle—”

“May God have mercy!” Morley Rogers shouted, raising the trowel in a shaking fist. Shorty disappeared from view.

“Next!” Morley Rogers demanded, and when, after ten seconds of leaden silence passed, no takers appeared, he said, “Very well, that’s it then. I’ll take your proposals under consideration. Remember, ladies and gentlemen, that while I may look old and feeble, I am also rich and well-protected. When I sold off the rest of the farm I made a small fortune, certainly enough to live on for whatever God-given time I have left. In other words, don’t hold your breath, don’t sit by the phone. I have no need of your money, no purpose for it, and I am happy living where I do. But, as I say, I will consider your proposals. I bid you farewell. Don’t knock anything over on your way out, don’t trip on the creepers, and don’t steal anything.”

The images disappeared, and the screen went blue.

Wheeler pushed “stop” on the remote.

Young leaned back in his chair and put his hands behind his head. “So what was the outcome of the meeting? After Uncle Morley got everybody’s balls in an uproar, did he sell the land?”

“No,” said Wheeler, “he kept it. Miss Sweet told me that once Mr. Rogers saw how much everybody wanted his land, he decided—out of spite, she said—to hang onto it. I guess he’s kind of eccentric. Considering how wealthy he is, he lives like a hillbilly.”

“What about Miss Sweet? What else do you know about her?”

“Well, she’s young—thirty-five or so—and she’s beautiful, as you saw in the video, and although she claims to be nothing more than his nurse and cook, I’d like to be a fly on the wall.”

“How long’s she been working for the old guy?”

“A little more than a year.”

“Myrtle,” he said. “I used to think that was an old woman’s name. Old-fashioned. Now it sounds kind of sexy. I wouldn’t mind meeting the woman.”

Wheeler smiled. “Drive up, why don’t you. She’s there twenty-four seven.”

“Maybe she’s after his land.”

Wheeler’s smile vanished. “That’s a thought.”

“Or maybe she’s in his will.” Young nodded to himself. “I wouldn’t mind having a look at it, just to know for sure.” He placed his hands on the arms of his chair. “All the rest of this information you got from Myrtle herself?”

“That’s right. She seemed to know everything about everybody.”

“She sure wasn’t shy about talking to you.”

Wheeler shrugged. “No. She sang like a bird. Which on the one hand makes me a little suspicious, like maybe she’s trying to deflect our attention, but on the other hand makes me think she doesn’t have anything to hide.”

“She wouldn’t let you talk to the old man.”

“True, but maybe he really wasn’t well enough to talk. She did pass along the video at his request.”

“Maybe it was her idea to show us the video.”

Wheeler sighed. “I don’t know what to think, but it wouldn’t surprise me one bit if she turns out to be exactly what she claims to be.”

“His housekeeper.”

“Right.”

“Right, and I’m Tom Cruise.” Young stood up. “Tomorrow morning, I’m going for a little drive in the country.”