Читать книгу Sweet Theft - J.D. McClatchy - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

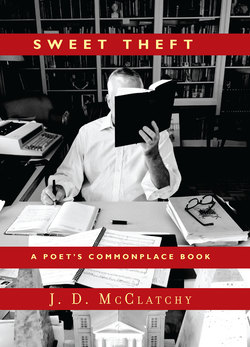

ОглавлениеI have from time to time kept both a notebook and a journal. They are very different things, as different as a recipe and the plat du jour. The one book I have scribbled in consistently over the past four decades, though, is my Commonplace book, a sort of ledger of envies and joys. “By necessity, by proclivity,—and by delight, we all quote,” Emerson observed. I have been drawn to turns of phrase or bits of truth, and the best are combinations of both—as in the work of that sublime revolutionary wit Oscar Wilde. But there is more to it than that. The sentences I hoard are images. And as G. K. Chesterton once wrote: “The original quality in any man of imagination is imagery. It is a thing like the landscape of his dreams; the sort of world he would like to make or in which he would wish to wander; the strange flora and fauna of his own secret planet; the sort of thing he likes to think about.” The bower-bird in me is forever collecting colored threads and mirror-shards to make a sort of world. My secret planet is populated by Diana Vreeland and Dwight Eisenhower and Alexander Pope and John Cage and Edgar Degas and Dizzy Gillespie and hundreds of others: a Mad Hatter’s tea party of brilliant conversationalists talking over and at odds with one another. I don’t use their remarks in my poems; I sometimes quote from them in my prose—and can be seen here gathering possible ways of expressing my scorn or admiration. There is also a recurring character, named X, to whom phrases happen. I have even included some musings of my own, pale by comparison with the wisdom of others but linked by the same impulse. I collect sentences because of the way, in each, something is put that is both precise and surprising. Twice-distilled poems? No. But an abstract model for the poetic. And if a poem is meant to be the light that casts a shadow, many of the entries in this book share the darkness of anyone’s skeptical or ironic sensibility. To minimize the risk of tedium, I have assembled here about half of the material I have copied down over the years. Haste and blurry vision may occasionally have introduced some errors into my copying, but if the odd word is off, the sense is there. The range of this book is narrow but high-minded. It limits itself to the sources of art, the relationship of the page to the world, and to aesthetic prowess. But any meditation on art, of course, is a commentary on the life—fetid or fertile, domestic or abstruse, deliberately provocative and endlessly varied—that inspires and sustains it. Proverb or remark, aphorism or anecdote, each gem contains a chaos and functions as a prism, allowing us to contemplate what we didn’t know we didn’t know.

“Commonplace” means proverbial wisdom. Sages from Cicero to Erasmus kept such books; they were meant to instruct, not to intrigue. Orators and students would study the snippets from moral philosophy and great poems. When books were rare and passed from hand to hand, the keeping of such scrapbooks became a way to preserve favorite passages before having to return the book to its owner. Milton and Leopardi, Emerson and Hardy, E. M. Forster and Alec Guinness kept them. In the eighteenth century, they became more personal and idiosyncratic. What once was considered an educational anthology the dictionary today defines as “a personal journal in which quotable passages, literary excerpts, and comments are written.” Emerson made it less a pastime than a noble cause, and gave it a revolutionary American slant: “Make your own Bible. Select and collect all those words and sentences that in all your reading have been to you like the blast of a trumpet out of Shakespeare, Seneca, Moses, John and Paul.”

One old term for a commonplace book was silva rerum, “a forest of things.” My own favorite is W. H. Auden’s alphabetically-arranged A Certain World, published in 1970, a constant wonder of discovery and annotation. Published near the end of his life, it is an emblem of the voracious appetite for knowledge that distinguishes his poems. He found appealing both the sacred and the camp.

This book is meant to be sipped, not gulped. It is not necessarily meant to be read from beginning to end, but to be dipped into, a page or two savored at a time. I hope you wander at will through my forest of things and take from it a part of the pleasure I had in transcribing what the leaves said and the birds sang.

JDMcC