Читать книгу A Notable Woman - Jean Lucey Pratt - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

23 January 1941

I want, I need a husband. Thousands of other lonely frustrated females must be feeling the same way – why should I think that I am to be luckier? Because I intend to try to find one. One must tackle the problem positively, gather together one’s assets, accept one’s debits and go forth booted and spurred.

Assets: A fair share of good looks, physical attraction, generous nature and more poise than I once had. Subjects about which I know something and can use in work and conversation: architecture, literature, drama, people and certain places.

Debits: an agonising, thwarting knowledge of my deficiencies and general unworthiness; a confused, badly trained, porous mind, a tendency to bolt into silence at the first advance of difficulty.

I must take them, my debits and assets, out into the world, into the battlefield … and there must I learn to fight. I may lose, but at least I shall know I have tried while there is still a chance of winning.

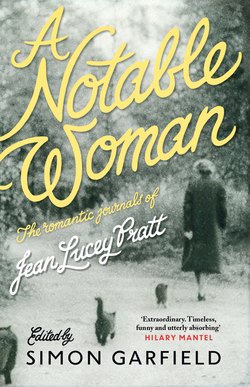

In April 1925, at the age of fifteen, Jean Lucey Pratt began writing a journal, and she didn’t put down her pen for sixty years. She produced well over a million words, and no one in her family or large circle of friends had an inkling until the end. She wrote – legibly, in fountain pen, usually in Woolworth’s exercise books – about anything that amused, inspired or troubled her, and the journal became her only lasting companion. She wrote with aching honesty, laying bare a single woman’s strident life as she battled with men, work and self-doubt. She increasingly hoped for posthumous publication, and her wish is hereby granted; the pleasure, inevitably, is all ours.

I first fell under Jean Pratt’s spell in the autumn of 2002, but she had another name then. I was visiting the University of Sussex, immersed in Mass Observation, the organisation founded in London in the late 1930s to gain a deeper understanding of the thoughts and daily activities of ‘ordinary people’. As the project evolved and the war began, hundreds of people agreed to submit their personal diaries, and Jean Pratt was among them. Most of the diaries (and diarists) were, of course, anything but ordinary: they were diverse, proud, intriguing, trivial, insightful, objectionable and candid. Most entries were handwritten, some were illegible. Some were composed on office paper, some on tissue. Mass Observation soon became a unique rendition of history without hindsight.

I had called at the archive with the intention of collating the material into an accessible book. Many of the diarists wrote from 1939 to the end of the war, but I was more interested in what came afterwards. For the book to work, I knew I would need to tell the story of recovery not only from a political and social perspective, but also from a personal one: the quirks and preferences of the diarists would have to be compelling in themselves, each voice overlapping in the timeline.

Over the next few visits I selected five writers who were different from each other in age, geographical location, employment and temperament. There was a socialist housewife from Sheffield, forever at odds with her husband and hairdresser; there was a pensioner from London, endlessly creosoting his garden fence and writing abominable poetry; there was a gay antiques dealer in Edinburgh; there was a curmudgeonly accountant, also from Sheffield, who got cross when fireworks woke him on VE Day.

And then there was Jean Lucey Pratt, whom I renamed Maggie Joy Blunt. (I changed all the names: this was in keeping with the broad understanding of Mass Observation’s founders and contributors – their words would be used as MO saw fit, but their identities would be protected, a liberating agreement, enabling frank contributions and freedom from prying eyes.)

Jean lived in a small cottage in the middle of Burnham Beeches in Buckinghamshire. During the war she had taken a job in the publicity department of a metals company, where the tedium almost swallowed her. She had been a trainee architect, but what she really wanted to do was write and garden and care for her cats. She took in paying guests; she read copiously; she hunted down food and cigarettes; and entertained her city friends. She researched a biography of an obscure Irish actress at the British Museum. And she kept track of her life in the most lyrical of ways.

My book was called Our Hidden Lives. It received generous reviews, and the success of the hardback helped the paperback become an unlikely bestseller. BBC Four made it into a film starring Richard Briers, Ian McDiarmid and Lesley Sharp, with Sarah Parish perfectly cast as Jean. Two further books followed – We Are At War and Private Battles, both prequels covering the war years – and Jean/Maggie was the only writer to appear in all three. Many readers claimed her as their favourite, and wrote asking whether there was any more. Fortunately there was more. Although Jean Pratt had died in 1986, she had a niece who was still alive. And the niece had treasures in the attic.

I had tea with Babs Everett and her husband at their house near Taunton in the spring of 2005. Babs, in her early seventies, was a familiar name to me: as a young girl she had appeared sporadically in her aunt’s diaries, once or twice living with her during the war; her aunt had once complained how untidily she had kept her bedroom; she once referred to her affectionately as the Pratt’s Brat. But now she was serving Earl Grey and lemon cake in her living room and wondering whether I’d like to see the rest of Jean’s writing. There were several boxes’ worth; she had kept diaries not just for Mass Observation, but during her entire life. Two fat folders contained about 400 loose pages, and then there were the exercise books, forty-five in all.

I sat with the journals at Babs Everett’s house for a few hours, and made notes. The sentences I recorded included this terse summation of her life to date, composed in 1926 when she was almost sixteen:

Bare legs and the wonderful silver fountain of the hose. Daddy in a white sweater. School. Very small, very shy. The afternoon in May – taken by mother to Penrhyn. Learning how to write the letters of the alphabet. A beautiful clean exercise book and a new pencil. Miss Wade at the head of the dining room table and me at her right. Choking tears because of youth’s cruelty …

Very small, very shy. I thought the journals were wonderful – not only their contents, but their physicality; not only the observations but the persistence. I thought immediately about the possibility of a book, but there were snags. Babs was keen on publication, but not quite yet; perhaps the British Library should have the diaries first. Three or four years went by while Babs attempted to find the best home for them. After several further conversations we reached an impasse, and I moved on to other work. I spoke to Babs again a few years later. She still had the journals, but again the timing wasn’t right.

In 2013, nine years after our initial meeting, I contacted Babs again. We had another good tea, this time at a friend’s house in another part of Somerset. We again talked of how best to bring Jean’s writing to a wider readership, but again there was hesitancy. I sensed that the journals were becoming a burden. And then a solution was found. Babs would bequeath the journals to an institution of which Jean would have approved – Cats Protection – and I would be allowed to edit them for publication.

In December 2013 three heavy boxes arrived at my home in London. The journals smelled faintly of tobacco; they were redolent of pressed flowers and meat paste. I felt privileged, daunted, and responsible. Most of the journals had remained unopened and unread since the day their writer had laid them aside.

How do they hold up, as much as ninety years on? Occasionally they are rambling, anti-climactic, inconsistent, repetitive and opaque, but for the most part they are a revelation and a joy. Not only fascinating to read and startling in their candour, but also funny, unpredictable and so engagingly and gracefully written that I couldn’t wait to turn the next page for further adventures. The questing displays of loving and longing (for romance, for life’s meaning) are brave and meltingly disarming; her devotion to her cats is heartbreaking; her comic timing owes something to the music hall. At times I felt like an intruder; at others a confidant; I wanted both to scold her and hug her. I found myself rooting for her on every page, willing her to win that tennis game or persuade a man to stay. The life that I had first encountered in her wartime Mass Observation entries now stretched back to her childhood in Wembley and forward to her old age, a snapshot transformed by a greater depth of field. I knew of no other account that so effectively captured a single woman’s journey through two-thirds of the twentieth century, nor one written with such self-effacing toughness. When friends asked me for a summary, I could think of nothing better than ‘Virginia Woolf meets Caitlin Moran.’

For the modern reader the journals provide many satisfactions. The writer’s emotions are universal and enduring: we empathise with her ambitions, disappointments and yearnings. Cumulatively, the journals envelop like a novel: the more one reads, the more one cares what happens next. I frequently thought of Jean’s latest challenge or calamity upon waking, and stayed up late to read the latest instalment. I recalled the crowd at the New York docks eager for the latest dispatch from Dickens: would Little Nell survive?

Jean Pratt was not Dickens, of course. She knew how to tell a tale – witness the way she ratchets up the tension over her schoolgirl crushes and her father’s new love. And she could draw the sharpest of portraits with a few deprecating lines (‘His good qualities seem to indicate a rather “might have been” goodness … a plant in decay,’ she writes of the man to whom she lost her virginity. ‘Not a flattering start.’) But there is no plot to speak of here (beyond the biographical one we all enact, the plot of existence and survival), and strands and characters sometimes disappear from sight as swiftly as they appear, without satisfying explanation. She writes that she would have it no other way: in January 1931 she quotes a writer she admired named John Connell.

It can be no tale of carefully rounded edges, of neatly massed effects, a thing of plot or climax. Somehow life is not like that – it is not symmetrical, measured and finished. The weaver of the pattern doesn’t seem to care for neatly tasselled ends and pretty bows – it is all very rough and ragged. Yet through it all there seems to run a purpose and an idea, a kind of guiding line.

Besides, life’s like that. And her journals are, after all, only writing; for all her searing honesty, she only records what she can bear to, and what she envisaged would be of value to her as she grew older (and perhaps of value to us after that). Value will date, of course. Not everything she wrote can be of interest to us today, but I was delighted to find that so much of it is.

Jean Pratt was made by the war. Like most who lived through it, the tumult transformed her far beyond the surface terrors and deprivations. Her writing matured, becoming not only more observant, but more worldly-wise. The drama of her war days, which assume a disproportionate weight in my edit, demonstrate the pure thrill of reading something so fresh that it appears still blottable. Completely lacking the hindsight of more familiar accounts, the pages brim with almost overwhelming poignancy: we know how the war turned out, she did not, and such is the power of her writing that we are flung back to doubt our own certainty. Will Hitler invade? Will Jean’s home be bombed? Will she aid the war effort? Is Churchill really the man for the job? Is this the night she finally gets laid?

There is far less writing after 1960. Her daily work becomes too time-consuming, her health worsens, and her introspection wanes. The more she knows about herself, and the more her world and ambitions shrink, the less she imagines a life beyond them. Between 1926 and 1959 her writing fills thirty-eight journals; between 1959 and 1986 there are only seven. But she kept at it. In the final years I do feel she was writing less for herself and more for her family and us, the unknowable reader.

At school she may have preferred botany to English, but words were unquestionably Jean Pratt’s craft and trade. Her drift into journalism and published biography seems at every stage a natural one (she made several aborted attempts at novels too). She read widely and wrote criticism, and then in later years she successfully ran a bookshop. Anyone who shares this passion for books cannot fail to recognise both a kindred spirit and a talented practitioner, nor marvel at the opportunity to witness a writer develop in style and intellect (let alone track a mindset from teenage naïveté to twenty-something disillusion to something approaching adult contentment). On a daily basis, the overriding value of her writing lies in the piecemeal narration and the telling details, the minutiae too often submerged in the bigger histories or airbrushed by heirs and estates. It’s a poetic list: the schoolgirl crushes, the depth of a grave as it appears to a child, the loss of a tennis match, bad car driving, classmates Yeld and Grissell, the dress-sense of Christians, the ‘Three Ginx in harmony’, the shock of Jacob Epstein, the disappointments of Jack Honour, the prominence of hunchbacks, the thoughts of war in 1931, the tears at a train station, girls playing cricket, the sodden film crew on a Cornish beach – the unfettered, absurd humanity of it all, and all this before she turned twenty-one.

How to sum up a life’s work? Certainly we may regard it as forward-thinking. She was clearly not the first notable woman to engage with the apparently mutually exclusive possibilities of spousal duty and career, but her modernity singled her out from her parents and the herd. She is not always the most humorous of companions, and her mood swings are often extreme (she doesn’t write when she is feeling really low). But her self-effacement more than compensates (and she is often funny without signalling the fact; she was aware of the Grossmiths’ The Diary of a Nobody, and occasionally I wonder if she is not extending the parody). At times her yearning for spiritual guidance leads her up some woody paths, but on other occasions she champions the principles of mindfulness long before it found a name. I admired her willingness to offend, although her wicked intentions never materialise beyond the page. But most of all I admired her candidacy, the raising of her hand. This is an exposing memoir, an open-heart operation. One reads it, I think, with a deep appreciation of her belief in us.

The dual responsibility (to Jean and her new readers) to deliver a volume that was both manageable in length and true to her daily experience – that is, something both piecemeal and cohesive – has resulted in a book incorporating only about one-sixth of her written material. Shaping her writing was a unique pleasure, but losing so much of it was not, not least because even the most inconsequential passages were refined with ardent beauty. In February 1954, for example, she looks from the window of her cottage. ‘Our world is frost-bound. Hard, hard, everything tight and solid with frost. I keep fires going in sitting room and kitchen, all doors closed. I fear there will be terrible mortality in the garden.’ Unremarkable in content, the words carry a heady poetic potency, the fine-tuned wonder of ephemeral thought. You will find a thousand similarly weighted reflections in the following pages, the work of a soul singing through time.

Looking for love all her life (from friends, from men, from pets, from teachers, from customers), Jean Pratt may have found her fondest devotees only now, among us, her fortunate readers. A quiet life remembered, a life’s work rewarded; Jean would have blushed at the attention. And then she would have crept away to write about it.