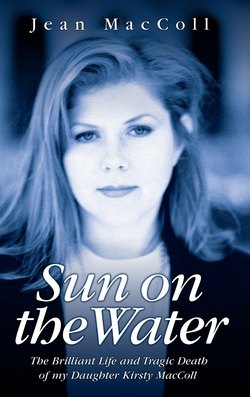

Читать книгу Sun On The Water - The Brilliant Life And Tragic Death Of My Daughter Kirsty Maccoll - Jean MacColl - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Christmas 2000

ОглавлениеThere was the Christmas tree, propped against the back door. I let myself into the silent house, Kirsty’s house, picking up her Christmas cards as I stepped onto the doormat. I could feel the desolation, the abandonment. Presents left on the office floor were waiting for her to wrap and put them with cards. The gifts she had already decorated had been put to one side. An atmosphere of loss filled every room. The hands that had been busy with so many preparations in the run-up to Christmas would never return to complete these celebratory tasks. It was a horribly vivid demonstration of a life suddenly cut short.

I put the kettle on and switched on the hall light so that the house might seem a little more welcoming, and waited for the taxi to arrive.

The doorbell rang, and through the glass I saw four figures peering in. I opened the door wide and hugged Louis first, and then Jamie, who winced – he was still recovering from abrasions and bruising to his side. Nobody seemed to want anything and the boys quickly disappeared into the lounge and started to play a game on the computer. James disappeared upstairs and Steve told me a little of what he knew. He said that Louis had cried on the flight home. I hoped this would help him – anything was better than this terrible numb sense of shock that had left us all like automatons.

Hamish came later, and James’s mother also arrived from the north. Steve’s new partner Patti and their young son arrived a day or so later. Then the boys’ friends from Bedales School started coming. I bless the school and the parents for letting their children come and stay over until Christmas Eve and return again later. I am sure their presence was vital to the boys in those early days of their grief. They slept in their bedrooms, which gave them the opportunity to talk if they wished.

The horror was still present in all our thinking and emotions were raw. Endless cups of tea and coffee were made, but many went untouched. I remember making shortbread with Louis and his friend Cosmo – anything to keep us busy. When the biscuits came out of the oven, one of them said, ‘Look, I’ve made a sun! Look at his smiling face,’ and sure enough there was a gingerbread man with a grin from ear to ear. I felt like hugging them.

Mutual friends started to arrive. James’s brother and the two Johns came over, and we ordered pizza for everyone, squashed around the dining table. It seemed right to me that all these people should be here. I am sure Kirsty would have wanted it.

Their love for her and the boys will be something I shall always be grateful for. But the time eventually came, on Christmas Eve, when everyone rejoined their own families and we were left alone.

The boys put up the tree and decorations without any help from the rest of us, following their mother’s example from previous years. Presents were put underneath the tree. Now what? We were all battling individually with tremendous grief and no-one seemed able to decide what we should do next. I took my strength from Kirsty, trying to imagine what she would want.

‘Why don’t we all sit around in a circle,’ I suggested, ‘put the tree lights on, and turn off the main lights? Let’s light a candle to Kirsty – she’s here with us. And, maybe, each of us in turn, can choose one of her songs.’

Hamish thought he wouldn’t be able to do that, but he joined in when the others agreed. Steve was the DJ. We each chose a favourite song as we went round the circle. After we’d finished, I commented on the quality of the sound. My own CD player, ancient and noisy, had recently packed up and we’d been using Kirsty’s equipment. I was surprised when some of them laughed.

‘It’s beginning to feel a little bit like Christmas now,’ said Jamie, quietly.

As the family members moved about, I think there was a slight easing of tension. Hearing Kirsty sing had been very therapeutic.

Louis was sitting next to me on the sofa. He asked me if I knew what had happened. I said I didn’t, but that I would be grateful to hear – but only if he wanted to tell me.

‘It will make you sad, Granny,’ he said.

‘I’m sad already, Louis,’ I replied.

It was then that he told me for the first time what had actually happened.

‘It was wonderful.’ Louis’s eyes lit up briefly at the memory of his first scuba dive. ‘Mummy loved the moray eels and the shells. I saw a lobster the size of my arm,’ and he measured it in imagination against his arm. ‘Then it was time to come up.’ They had all been given instructions by Ivan, the dive-master, and Kirsty had warned them to follow his rules precisely.

‘I was the first to come up,’ continued Louis, ‘then Mummy, and then Jamie. I looked at Mummy and she smiled and said, “Wow!” And I said, “Great!”’

Jamie had surfaced just as a warning shout alerted all four divers. Kirsty, with her back to the danger, turned her head to see the powerboat almost upon them. Louis said it was travelling at high speed and high enough out of the water for its propellers to be visible. Kirsty managed to push Jamie and Louis out of the way before the boat struck her. She saved their lives. Louis turned around and followed in the wake of the boat.

‘I was swimming in Mummy’s blood. I heard Jamie calling out, “Where’s Mummy? Where’s Mummy?” I told him not to look. “Don’t look, Jamie! Get back to our boat, look the other way!”’

That was all I could take in at the time. I was to find out later that Guillermo Gonzalez Nova, one of Mexico’s wealthiest businessmen, was the owner of the powerboat, and had been on board with his two grown-up sons. Witnesses later told me that my grandsons’ cries of distress were clearly heard as they were left bobbing in the water with their mother’s body. It was others who called for assistance: the first to do so was the captain of a fishing boat who had tried without success to divert the course of the powerboat. I thanked Louis for telling me, and we sat together for a while. It was to be several years into our investigation before I heard how the boys had been left alone, ignorant of what was going on.

Kirsty’s partner James had stayed behind to do some reading at their rented accommodation and, having been under the impression there had been a minor accident, he took the car to the harbour. When he arrived he was not allowed to go too close to the water’s edge. No one would answer his questions as to what had happened, and in desperation he had got out of the car and screamed, ‘What the hell is going on? Why doesn’t anyone tell me something?’ Hearing his voice, the boys suddenly ran into his arms, telling him that Kirsty had been killed, and Jamie cried, ‘What will become of us now?’

James took them home – but still no one came to tell them anything at all. (Presumably, it was at this point that Guillermo Gonzalez Nova was busy sending for his lawyers from Mexico City to fly in and give evidence on his behalf. Ivan, Kirsty’s diving master – not being a wealthy ‘Don’ – had to wait over 24 hours before being allowed to give his evidence.)

It was now almost midnight on Christmas Eve, 2000. Soon it would be Christmas Day, and I dreaded it. I looked for the large turkey we always had, thinking to prepare it for the oven and was surprised to find a box containing a smaller bird than I’d expected. It turned out that the butcher had changed the order after hearing the news. I went to bed. This turkey would only need a couple of hours at most.

The presents under the tree were handed out, as usual, at around ten o’clock on Christmas morning. I had two presents from Kirsty. The first was a large box which turned out to be a new portable hi-fi system. So that was why everyone had laughed the previous night: she had decided to replace my defunct machine and the boys had known about it. Her other present was a pair of non-slip socks for my tiled kitchen floor.

The television channels played ‘Days’, over and over again, in Kirsty’s memory and I felt comforted to know that other people cared. Somehow we got through the day, pulled our crackers, briefly wore the silly paper hats and raised a glass to Kirsty. Afterwards everyone disappeared, perhaps to try to catch up on their sleep.

On Boxing Day morning my old friend Joan Littlewood, godmother to both Kirsty and Hamish, came to see us. We had first met when I visited the Theatre Workshop company, which she and Ewan MacColl had founded – as its director and playwright respectively – in 1946. Both were fascinated by Rudolf Laban’s ideas on movement, and had written to Laban himself, asking if he might spare someone to train their actors. As his assistant, Laban asked me to visit the company. Joan and Ewan had been briefly married before the war, but when I met them, Joan had begun an enduring relationship with Theatre Workshop’s business manager, Gerry Raffles, and Ewan was unattached. He and I fell in love, and were married in April 1949.

Joan talked in typical fashion about everything except the accident – that was too hard for her to confront. She brought me a beautifully bound book on French dance. I knew that the book represented everything she felt unable to say in words. She had always, whenever possible, been there for Kirsty during her childhood, and had later chosen to spend a period of convalescence with Kirsty and Steve. Now 85 years old, she looked frail. I encouraged her to have a snack and a glass of wine, and then Steve offered to drive her home. By the time he returned, the boys’ friends were back for an overnight stay – I think they had organised a visiting rota among themselves.

Musician friends came and went over the next few days, during which the phone seemed to ring constantly – Sarah, from the music company, Ronnie, Kirsty’s friend and executor from South Africa, the funeral directors and crematorium, friends, many from overseas and an engagement in Chicago that had had to be cancelled. There were many loving letters and cards that had to be answered and many more, I’m afraid, that weren’t. The postman handed me his own bouquet of flowers.