Читать книгу Like a Tree - Jean Shinoda Bolen - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Tropical Rain Forests and Boreal Rain Forests

ОглавлениеBoth tropical rain forests and boreal forests are being destroyed at an alarming rate by humans for economic reasons. In an article in National Geographic (Wallace, “Last of the Amazon,” January 2007), Scott Wallace began with the sentence: “In the time it takes to read this article, an area of Brazil's rain forest larger than 200 football fields will have been destroyed.” Industrial-scale soybean producers are joining loggers and cattle ranchers in the land grab. Roads are cut through the forest to make valuable hardwood trees more accessible and transportable. In the Amazon, there are more than 105,000 miles of these roads, almost all made illegally, which then are used by squatters, farmers, and ranchers who clear the land by burning off the underbrush and trees that remain.

As indigenous people intuitively grasp, the benefits the Amazon provides are of incalculable worth: water cycling (the forest produces not only half its own rainfall, but also much of the rain south of the Amazon and east of the Andes), carbon sequestering (by holding and absorbing carbon dioxide, the forest mitigates global warming and cleanses the atmosphere), and maintenance of an unmatched panoply of life. But there haven't been profits in keeping the forest. Money is made by logging and by cutting it down for grazing and farming, not by leaving it standing.

Twenty percent or more of the Amazon rain forest has been cut down so far. When another 20 percent is destroyed, scientific expectations are that the forest's ecology will unravel. This would reduce the amount of rainfall that the forest produces through the moisture the trees release into the atmosphere. To this, add global warming: remaining trees then dry out, leading to droughts and susceptibility to fire. Amazon forest fires burned unchecked for months during the record drought of 2005–2006, followed in 2007 by the worst rain-forest fire in history. Smoke releases tons of carbon dioxide and other pollutants into the air, directly raising the ambient temperature, and further contributing to global warming by the production of more greenhouse gases. The deforestation story is the same in Indonesia, the country with the largest tropical forest in Southeast Asia, which replenishes fresh water and has a key role in weather and climate.

Whether my concern is about one tree or forests, one person or humanity, I learn what I need in order to grasp a situation that affects a species or a class of people (children, women, race, or religion) by paying attention to an individual that is representative. I want to see the forest and the trees, a metaphor that became literal. I learned from my Monterey pine that pine needles condense fog into lots of dripping water. Next I learned from others that trees also send water upward from groundwater; they transpire it from roots through leaves. Colin Tudge wrote that a big tree can transpire 500 liters (528 quarts) in a day.

In Tree: A Life Story, David Suzuki and Wayne Grady explained how one tree adds to the big picture: “A single tree in the Amazon rain forest lifts hundreds of liters of water every day. The rain forest behaves like a green ocean, transpiring water that rains upward, as though gravity were reversed. These transpired mists then flow across the continent in great rivers of vapor. The water condenses, falls as rain, and is pulled back up again through the trees. It rises and falls on its westward migration an average of six times before finally hitting the physical barrier of the Andes mountains and flowing back across the continent as the mightiest river of Earth” (2004, p. 68). This particular description captured my imagination and thereby my understanding.

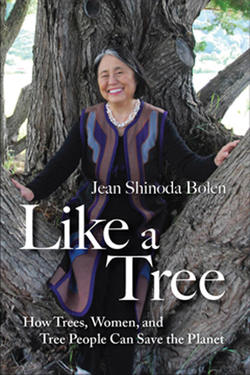

The North American continent has its own vast, endangered boreal forests of conifers. In the waiting room of my optometrist, I picked up a six-month-old copy of Audubon just after I decided to write Like a Tree. In it, journalist T. Edward Pickens described Canada's boreal forest as “an emerald halo of woodlands, wetlands, and rivers that mantles North America. This is the greatest wilderness on the continent, a 1.3 billion-acre forest stretching from Newfoundland all the way to the Yukon. The Canadian boreal holds a quarter of the world's forests and most of its unfrozen freshwater, and sequesters 1.3 trillion metric tons of carbon” (“Paper Chase,” January–February 2009). More than three hundred species of birds breed there, and as many as five billion individual birds fly south from the boreal each autumn. These trees are being clear-cut to make paper, for books, catalogs, paper towels, and toilet paper. There are clear-cut areas measured in square miles. In an issue of National Geographic (June 2002), I learned that boreal forests have more wetlands than anywhere else in the world. Those in Russia and Canada each contain an estimated one million to two million lakes and ponds.