Читать книгу Artemis - Jean Shinoda Bolen - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

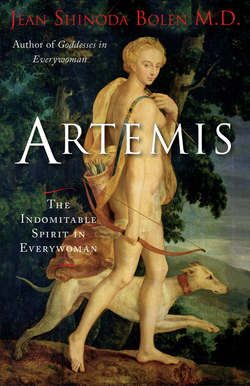

Introduction The Indomitable Spirit in Everywoman

Оглавление(Latin in + domitare: to tame; incapable of being subdued or tamed)

Indomitable spirit is an attribute in women who have Artemis as an active archetype. In mythology, Artemis is the Greek Goddess of the Hunt and Moon, known as Diana to the Romans. She was the first-born twin sister to Apollo the God of the Sun. As goddess of the hunt, she roamed the wilderness, armed with a bow and quiver of arrows, accompanied by her hunting dogs, either alone or with her chosen nymph companions. Artemis came to the rescue of her mother, was the protector of pre-pubescent girls and young animals. Pregnant women prayed to her to relieve them from pain. (Artemisia—the herb that bears her name, is used by midwives for this). She reacted swiftly to help those under her protection and to punish those who would harm them or disrespect her. Artemis is an archetypal predisposition toward egalitarian-brotherly relationships with men, a sense of sisterhood with women, the ability to aim for a distant target or rise to a challenge, and a preference to be in nature rather than cities.

Artemis: The Indomitable Spirit in Everywoman is a coming-full-circle book. I go back to the story of Atalanta that led me to write Goddesses in Everywoman: A New Psychology of Women, a book that initially became an unexpected best-seller, then a classic, celebrated by the publication of its thirtieth anniversary edition in 2014. It began as an entirely different book about two paths of feminine development with the working title Pathways to Wholeness. It was based on Greek myths about Psyche and Atalanta, two mortal women, one identified with Aphrodite, the other with Artemis.

In Jungian literature, the myth of Psyche is the model for the psychological development of the feminine psyche. While it does apply to many women, to say that this was the pattern for all women did not ring true for me. Psyche was the mortal woman who offended Aphrodite. Pregnant and abandoned by her lover, she tries to drown herself and finds she cannot. She then is given four tasks to complete and is initially overwhelmed by each task. Symbolic helpers then come to her rescue (each represents an inner resource that she did not know she has) and as the tasks are done, she grows psychologically. I wanted to find another myth that would apply to women who took on challenges, ventured into new fields, defined themselves, and who entered occupations and professions that had traditionally been male stronghold—women who were at ease with men as friends and equals. I found Atalanta.

My focus expanded after I wondered: What about the other Greek goddesses? And then, as if in response to this question, Hera, Goddess of Marriage, “appeared” in the psyche of a woman who had been taken over by Hera in her jealous aspect. My interest shifted to the major goddesses in Goddesses in Everywoman. As a result, only remnants of the Atalanta story remained, at the end of the Artemis chapter, and Psyche's four tasks were incorporated into the Aphrodite chapter.

My interest in Atalanta was renewed the summer before I began writing this book, when I taught at the C. G. Jung Institute in Kusnacht, Switzerland for the first time. Kusnacht is Jung's hometown on the shore of Lake Zurich and, although I did not train there, I think of it as the “mothership” of Jungian institutes. For the first time in over a decade, I told the myth of Atalanta and amplified its meaning to an international student body. It came alive in me and in the room. I remembered why I had become interested in Atalanta in the first place.