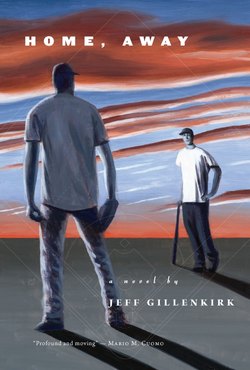

Читать книгу Home, Away - Jeff Gillenkirk - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSTRIKE TWO

Top o’ the 10th ...

Tobias Barlow USA TODAY

In the male bastion of baseball, fatherhood is a large, yet largely unspoken subject. I’m sure it’s hard to focus on your littlest fans when thousands of others are praising you night after night on fields of play. But all that changes when those littlest fans don’t have the opportunity to see their daddy, or vice versa. Absence makes the heart go ponder.

Kids, ironically, were the subject when I caught up with Cincinnati Reds’ lefthander Jason Thibodeaux at the Margaret Adams Strohmeyer Senior Center in downtown River City. On home stands Thibodeaux serves lunches and assists the physical therapy staff with the rehab of elderly patients who have had their hips, knees and other worn parts replaced. He’s here, he says, because he can’t stand the sight of kids.

After losing a child custody battle, Thibodeaux sees his 8-year-old son, Raphael, only during the off-season — and on the single road trip the Reds make to San Francisco, where Raphael lives. Under a court-enforced formula, Thibodeaux and his son spend an average of six weeks out of fifty-two — every other weekend and every other Wednesday for four months, and that one precious road trip to the Golden Gate.

A lot of ball players work with youth, but Thibodeaux went the other way. “Every time I see a group of kids I think of Rafe and how much I miss him. Plus I get a lot of satisfaction working here. I never had the chance to take care of my own parents, so this is a way of paying them back.”

Not that some of his current charges don’t act like kids. After lunch, a man rolls up in a wheelchair and thrusts a copy of Sports Illustrated into Thibodeaux’s hands, who pens ‘Best Wishes, Ted’ and hands it back. “He says it’s for his nephews, but he’s got dozens of these in his room,” Thibodeaux laughs.

Thibodeaux has struggled on the mound this year — he’s 8-11, with a 4.37 ERA. But to the residents of the Margaret Adams Strohmeyer Senior Center, he throws a perfect game every time he shows. The fan he cares most about, however, isn’t here to see it.

THE REMOTE-CONTROLLED BIG WHEELS “HOT ROD” lay overturned on the carpet. There was a tabletop Air Hockey game from Ryan Habbegger and his mom, Sam Trainor’s silly “Booger Sculpture” kit, a 10-pound bag of multicolored marbles, a biography of Beethoven, and a dozen or more classical and jazz piano CDs scattered amidst torn wrapping paper and ribbons on the living room floor of Vicki’s townhouse on Diamond Heights in San Francisco. There had been pizza and crudités, cake and ice cream and candles, and on cue Rafe’s buddies Laslow Samuels and Angel Villanueva from the Aurora Craverro School of the Arts had broken into a version of “Happy Birthday” on a piccolo and kazoo as the two delivery men from Sherman Clay wheeled the shiny new Yamaha upright into the room with a fancy candelabra blazing on top.

The party was over, the guests gone, the methodical plunkings of Rafe’s shortened version of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Sonata #2 a fastfading memory. Rafe sat at the kitchen table overlooking Glen Canyon, his fingers speeding along the Acer keyboard playing “Major League Baseball 9.0”. The laptop and software from his Dad arrived by DHL just that morning in a big yellow box addressed to Master Raphael Thibodeaux. His friends thought it was cool that his father was a Major League baseball player, though that wasn’t such an easy thing. His mother said that baseball was for morons, which didn’t make much sense as his dad wasn’t a moron, but still, it would have been easier if his dad was a musician because that was what his mom loved most. Baseball took his dad all around the country and Rafe hardly ever saw him during the season. He had only seen him play once in person, and never on TV — though that was about to change. The Craverro School didn’t allow students to watch television or use computers until they were eight. Today he was eight.

“Rafe!” his mother called from the living room. “Time for bed.”

He glanced at the kitchen clock. “It’s only nine o’clock.”

“Which is your bed time. C’mon.”

He wasn’t sure who hit it but a single flared through the Orioles’ infield and Rafe, pulling the fielders in, threw the runner out at second trying to stretch the hit. It was a great game, the players responded to his slightest touch, flinging fastballs, flying vertically along the grass to spear line drives, reaching above the wall to steal home runs from bigshouldered sluggers like David Ortiz and Ryan Howard.

“Rafe.” Vicki stared at him from the living room doorway.

“Mom, it’s my birthday!” He was a slim, lanky boy, just half a head shorter than his mother. He had a long trunk and long legs and strong arms like his father’s, and his mother’s slim graceful face, dark brown eyes and olive complexion. He glanced quickly at the screen. The players waited silently for his commands.

“And you’ve had a wonderful day,” she said gently. “Now turn that off.”

He pressed “off” and the world of Major League Baseball vaporized. Vicki put her arm around him and they walked together toward the living room. “Did you have a good time?” Rafe nodded. They stopped beside the piano, its bulkiness a formidable new presence in the townhouse. “How do you like your new piano?”

“Good,” he responded. Then, “Thanks for the party, Mom. The pizza was really good.” She squeezed his shoulder just as the phone rang.

“It’s probably your father,” Vicki said, reaching for the phone. “I need to talk with him first.”

“You guys’ll just fight,” Rafe said glumly.

“Just for a second … Hello?”

“Hi.” It was Jason. “Is the birthday boy there?”

“He’s here. He’s a little tuckered out from his party.” She smiled towards Rafe, who shook his head vigorously. “He got a piano for his birthday!”

“I wonder who got him that?” Jason replied. “Let me talk with him.”

“Did you ever find that red sweater my father gave Rafe for Christmas?”

“I told you, I have no idea where it is. I’ve never seen it.”

“Could you look for it? He says he left it there.”

“It’s not here, Vicki. Put him on, will you please?”

“I know I packed it, the last time he went to Cincinnati — ”

“You mean the one time you let him come here and visit?”

“ — and now we can’t find it. It was a special gift from my father.”

“Mom, it’s not important,” Rafe called out. “We can get another one.”

“I don’t have the faintest idea where it is,” Jason said. “Would you put Rafe on? I didn’t call to talk to you!”

“Just take a minute and look, will you please? That’s not too much to ask.”

There was a pause, then Jason’s voice, low and tight. “I’m paying you four thousand dollars a month and you’re bitching about a fucking sweater? PUT RAFE ON THE PHONE!”

Rafe was already on the way to his bedroom when Vicki hung up. “He’ll call back later,” she said. “He just needs to calm down.”

CHARLIE GIORDANO flashed four gnarled fingers, then 2-2-4-2-2 and set up for a slider, low and inside. Jason gripped the ball along the inside of the seams, stretched his arms slightly away then back to his body, and turned his head to check the runner at first. Ray Burriss leaned towards him, glove open, and over Ray’s shoulder he saw the kid. Eight or nine years old, wearing a Giants cap and a white t-shirt and a look of rapturous concentration on his face, his right hand tucked inside his baseball glove, watching, waiting with the man beside him, his dad no doubt, a father and son out on a warm summer evening in Cincinnati for the timeless American past-time of baseball. Maybe the kid was living with his father, or it was visitation day. That was it — tonight was Wednesday! The night that every divorced Dad who couldn’t be a Dad got to play at being one with their “visitation rights.”

Jason stepped off the rubber and scuffed the dirt, thinking of the last time he had seen Rafe, in San Francisco. He had gotten him a seat in the owner’s box with some friends from school, and he would never forget the look on Rafey’s face when the public address announcer broadcast “A Giants’ welcome to the students of Aurora Craverro School and to Raphael Thibodeaux, son of Reds’ pitcher, Jason Thibodeaux. Welcome to the Big Leagues, Rafe!”

That was two months ago.

He rubbed the ball and looked toward the kid. Maybe the guy wasn’t the kid’s father. Maybe it was his stepfather, or a neighbor, or his mother’s boyfriend — some guy he doesn’t really care about and his real father was gone, pissed off, hopeless. Jason’s eyes swept the stands. He’d been playing baseball since he was four; it had always been his refuge. The bellowing of his father’s drunkenness or the silence of his indifference evaporated in a crowd roaring at a called third strike or a bang-bang double play. His mother’s sobbing in the ice-bound bungalow in Port Barrow melted in the chatter of infielders calling his name. But now all he could think of was Rafe. What was he doing? What would he think if he were here watching the game? How did he end up two thousands miles away from his son?

“JT.”

He was surrounded — Giordano and Burriss and Vucovich, who’d come to the Reds the same time as he, and the shortstop, Carlos Guardell. The umpire hovered impatiently behind Vuco, his mask off. Voices in the crowd shouted for Jason to pitch.

“What’s going on?” Vucovich asked. Jason shrugged.

“Is it your arm?”

Jason shook his head. Guardell whacked him on the rear end with his glove and trotted back to shortstop. Vuco leaned in close. “I’m comin’ over for breakfast tomorrow,” he growled. “And I want pancakes. Now get this guy out.”

Giordano signaled again for the slider, low and inside, but Jason shook him off. He wanted to throw heat. He wanted to throw a pitch so fast that even the batter would be giddy with awe as it screamed into the catcher’s mitt. Finally Giordano gave in — fastball, outside part of the plate. One more out and he had a complete game. Not a pretty one, 5-4, eight hits, two of them home runs. But the guys had come through and all he needed was one more out and they could go out for some beers and follow the score from LA.

He went into his stretch and checked the runner — and there was the kid again. He kicked and unleashed the fastest ball he could throw, and he knew instantly that he would never see it again. It streamed down the center of the strike zone and just as quickly reversed, taking the most direct trajectory deep into the left field bleachers. He heard the collective groan of the fans and watched his teammates trot towards the dugout.

VUCO SHOOED a yellow jacket off the syrup-soaked pancake, cut off three pie-shaped pieces and speared them with his fork. He chewed for a moment, then pushed the plate away. “I can’t believe your kid likes these things. They taste like shit!”

They sat on the broad brick patio behind Jason’s four-bedroom house in Park Hills, Kentucky, across the river from Cincinnati’s River Front Stadium. An unlandscaped half-acre sloped down to a stream between his house and his neighbor’s two hundred yards away. A single tree broke the expanse of weeds and grass. A golf club and a pile of balls sat nearby on an Astroturf mat.

“You’re going into therapy,” Vucovich said.

“Fine,” Jason replied. “But I still want a trade.”

“Let me guess — San Francisco?”

Jason pointed at Vuco’s plate. “You want some more?”

“Not on your life.” Vuco gazed over the enormous expanse of lawn. “Why don’t you get some cattle or something?”

“Nobody to take care of ‘em.”

“Get one of those au pair girls. You can get ‘em on the Internet now.”

“That’ll look great in the papers. ‘Thibodeaux Hires Online Concubine.’”

“I’ve seen worse.” Vuco picked up the nine-iron and hooked a ball sharply towards the stream. He tossed the club aside and turned on Jason. “You’re gonna kick yourself in the ass big-time for not taking your shot seriously.”

“C’mon, Vuco. If anything, I’m taking it too seriously.”

“Horseshit. You’re stuck in some endless re-enactment of the Alamo, losing the same battle over and over again and loving every second of it.”

“I don’t love it. Do I look like I love it?”

“Then why do you keep doing it?”

“I’ve had this same bullshit custody schedule for five years now.”

“Then you should be used to it.”

“Seeing him two times during the season? Fuck that.” Jason gazed with a far-away look over the half-finished suburban neighborhood. “I miss him, man. I can’t be his father if I’m not playing in the same town.”

Vuco shook his head in exasperation. JT was his creation. He was the one who scouted him in Galveston and recommended him for scholarship; who’d brought him to Billings after they passed him in the draft; who’d worked with him hour after hour in the far flung stadiums of the Pioneer league, teaching him a changeup, a splitter, a new pick-off move — and the one who brought him up to the Reds. Again and again he’d put his reputation on the line for Jason Thibodeaux; and now he wanted a trade.

“They can’t move you the way you’re pitching.”

“Then I’ll pitch better.”

“That’s what I mean about taking it seriously.”

“I’m sorry, Vuco. I’m just doing what I have to do.”

“What you have to do is win baseball games.”

“Fair enough.”

Vuco’s expression grew visibly softer. “We go back a long ways,” he said, clearly uncomfortable with what he was about to say. “I respect what you’re doing — on the homefront,” he added quickly.

“Thanks, Vuco.” Jason rose and stepped towards his tightly-wound coach. Vuco raised his hands as if he were holding a runner at third.

“No hugs, man.”

Jason hugged him anyway. Vuco didn’t hug back but neither did Rafe half the time. That didn’t mean he didn’t appreciate it.

“I still want you to go into therapy,” Vuco said.

“And I still want a trade.”

SYLVIA HLUCHAN was a sports psychologist who had once been involved in a highly publicized case in which she was hired to hypnotize the entire University of West Virginia football team before its seasonopener. The fact that the team eventually went 2-8 that year did not diminish the fury of the public ridicule around the opening game loss to Ohio State by a score of 55-3. Dr. Hluchan did not take the criticism lying down. “To be subconsciously convinced you are an excellent football team when you are not, no more guarantees positive results than if you are hypnotized into believing you can fly, only to plunge to your death off a cliff,” she said in an article for the Pittsburgh Press posted on the wall of her waiting room. “The next time I’m recruited for a job like this, I’ll be sure to consult a scouting report as well as Las Vegas odds makers.”

Her waiting room wasn’t much bigger than a closet, with two straight-back chairs, a small table with back issues of various magazines, that morning’s Cincinnati Inquirer, and a single potted plant that looked just hours from death. Jason picked up the sports section and glanced at the box score from last night’s game: Houston 9, Reds 0. Teddy Driscoll, their ace righthander going for his sixteenth win, gave up six runs in the third inning and they never recovered. They were four games out with three weeks to go and had no more games with the front-running Cardinals.

His thoughts were interrupted by the appearance of a small elderly woman with stiff white hair and thick glasses. “Come in, Mr. Thibodeaux,” she said in a no-nonsense voice. She led him into a small, windowless room and motioned to a chair beside a messy desk. She leaned forward from her worn blue easy chair and offered her hand. It was surprisingly dry and delicate, as soothing as talc. “I’m Dr. Hluchan,” she said. “Why don’t you tell me why you’re here.”

“Why?” He’d never been to a shrink before and didn’t know what he was supposed to say. “I pitch for the Reds — the Cincinnati Reds. Bill Vucovich recommended you … ” She stared at him, her blue eyes magnified to startlingly huge orbs by the lenses of her glasses. He tried to adjust himself upward in the chair, as somehow he was sitting lower than the tiny therapist. But no matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t get himself up to her level.

“I’m here because I’m a lousy pitcher, I guess,” he finally said.

She shook her head. “You’re here because you’re a fine pitcher but you’re not pitching like one. Tell me what’s going on in your life.”

He took her back to the day Vicki left with Rafe, then told her about their divorce, the custody battle, the rigid visitation schedule — his ex-wife’s refusal to exchange the two weeks allotted during summer vacation with Rafe for time at Christmas or Thanksgiving. “On top of that, she’s late all the time — an hour, two hours, sometimes more. Or she’ll call and say she’s got special plans, or that Rafe’s sick and needs to stay in bed.”

“Is he sick?”

“It doesn’t matter, I’m perfectly capable of taking care of him,” he said defiantly. “I like taking care of him when he’s sick.”

Dr. Hluchan leaned forward in her chair. “You gave a very compelling story about why your ex-wife should see a therapist, Mr. Thibodeaux. But what about you?”

“What about me?”

“How do you respond to her behavior?”

Jason squirmed. “Like an asshole.”

“Examples please.”

“She brings him two hours late on a Friday, I’ll bring him back two hours late on Sunday. He’s sick on a Wednesday and can’t make it, I’ll claim that he’s sick on Sunday and can’t make it back to her house. She won’t answer her phone when I call for Rafe; I won’t answer when she calls for him at my house.”

“You really do sound like an asshole,” she smiled. Jason looked up in surprise. She was a tough old bird, he liked her. “Do you fight in front of your son?”

He nodded. “I can’t help myself. I just hear her voice and it’s like the bell in a boxing match.”

“A match you absolutely have to win.”

“Exactly. That’s the way I am — I want to win.”

“Win what?”

Jason stared at her, half-smiling in embarrassment. “The battle.”

“The battle for what?”

“The battle with my ex-wife! The battle … ” his voice trailed off.

“You won that battle, Mr. Thibodeaux. You were convinced your ex-wife thought you’d disappear and you didn’t. You stayed to fight another day, except this isn’t a fight. You were given the extraordinary opportunity of raising a child and you went about it the best way that you could. You say you read books, you interviewed child development experts, you talked to mothers, fathers, kids about the best way to raise your child. So why did you stop?”

“I didn’t stop. When the courts took him away I couldn’t — ”

“Courts shmourts. You took yourself away. You chose to play baseball and that’s OK — you’re a baseball player. Like I’m a therapist and your wife is a lawyer and your kid is a kid. Your ex-wife could be a lot more cooperative in this venture, but then she wouldn’t be your ex-wife, would she?” There was the smile again — or at least, the shape of one. Jason stared. “Now you have the extraordinary challenge of loving and caring for that child despite all this. And what are you doing about it?”

“I’m doing the best I can.”

“Are you?”

“Of course I am! What the hell else would I do?”

“Come on, Mr. Thibodeaux, you graduated from Stanford.”

“Yeah, well, all the books say cooperate. But when I see her — ”

“Him, Mr. Thibodeaux. We’re talking about him.” Jason looked at her questioningly. “Do you ever make videotapes or audio tapes of you reading stories or talking to him?” she asked.

“No.”

“Do you ever have a pizza delivered to his school for lunch, just to surprise him?”

“No.”

“Do you ever send him postcards from cities where you’re playing, explaining interesting things you’ve discovered and asking him what he’s doing?”

“I asked for a trade to be near him,” he offered.

She waved his words away. “You’re a National League pitcher. I prefer the National League because pitchers challenge hitters — strength against strength, fast ball pitcher to fast ball hitter — am I right?” Jason nodded. “But every once in a while you’ve got to throw a curve,” she continued. “You’ve got to drop one off the edge of the table and leave them standing there with the bat in their hands, wondering what the hell just happened.”

Jason arched an eyebrow. He couldn’t figure out where she was going, whether they had just switched to baseball or she was weaving some kind of complicated spell that would leave him in the same straits as the University of West Virginia football team.

“Your ex-wife is hitting your fastball,” she said. “She’s a lawyer, and you’re pitching right out over the plate — fast ball fast ball fast ball. You’ve got something huge that you haven’t used yet, a secret weapon that every man has to discover before he can conquer the world.” Sylvia Hluchan tapped her chest beside a small pearl brooch in the shape of a chrysanthemum. “Your heart.”

The small clock on her desk ticked softly. Jason realized with surprise that the hour had passed. Herds of questions stampeded through his mind. What if Vicki won’t let Rafe play the tapes? What if she throws away the postcards? What if Rafe’s friends think his Dad is crazy for sending a pizza to school — or worse, what if Rafe does?

They rose together. Sylvia Hluchan’s head didn’t even reach his chest. “I think the Reds thought we’d talk about baseball more,” Jason said.

“We did.”

“About my pitching, I mean.”

She hooked him by his left arm and led him into the waiting room. “We determined at the beginning that you’re a wonderful pitcher. That hasn’t changed in the last hour.” She stopped and looked up at him. “I want you to come in next homestand and tell me how you’re doing.”

“Do I have to?”

“Yes.” She gave his arm a squeeze before letting him go. “Keep throwing strikes, Mr. Thibodeaux.” She smiled her strange smile, her eyes expanding behind the thick glasses. “Just change speeds once in awhile.”

IT WAS, as Yogi Berra said, déjà vu all over again. A man on first, the Reds up by a run, eighth inning, the count 2-2 and Giordano calling for a slider low and outside. Jason took a deep breath and went into the stretch and there was the kid again with the Giants hat, sitting in the front row beside the same heavy-set guy eating popcorn.

Jason’s eyes locked on the kid, then he stepped off the rubber and smiled to himself. Maybe Vuco was right — maybe he was crazy. Maybe at some point next year — next week — they’ll be pulling him off the backstop like Jimmy Piersall in Fear Strikes Out. Stranger things had happened.

“Andale, Ya-sone,” Guardell whistled from shortstop. “C’mon, JT!” Digger Wells called from third. He glanced into the dugout and saw Vuco staring, posed like Baptiste used to be, his hands in his back pocket, his back curved, pelvis thrust forward.

Jason checked the runner, kicked and the pitch was off — a missile headed straight for the heart of the plate. The batter strode forward, his bat seeking the tiny orb but it broke down and away into Giordano’s mitt.

Strike three!

He strode to the dugout and accepted a fusillade of high fives. “JT! JT! JT!” player after another barked affectionately. It was a cold Monday night in mid-September and the Reds were still four-and-a-half games out and nobody believed they were going to make it except them. Everyone was playing well — and no one was playing better than Jason Thibodeaux. With two more wins his record would be 12-12. Two wins put at least another zero on his contract, and his agent could move him to San Francisco.

He stopped at the cooler and tossed down a cup of cold water. Vuco came up behind him. “I’m bringin’ in Jervey to finish,” he said. Jervey was their closer. Jason’s face fell with disappointment but Vuco clapped him hard on the shoulder. “You keep pitching like you did tonight, you can go anywhere you want.”

JASON SAW the light on his phone blinking as he entered his hotel room after the game. He looked at his watch — Wednesday. He quickly dialed the message box. “You have two messages. To listen to your new messages, press one — ”

He punched one. “JT, it’s Digger. I met a dish and can’t make dinner tonight.” Goddamn Wells, he’d stand up the Pope if some babe got to him first. He erased the message, then waited for the other. “Hi Daddy, it’s me, Rafe. Are you there? I’m wondering if you’re still working or at a party or where you are.” There was a long pause, Jason was afraid he’d hung up. Then, “Hello? Are you there Daddy? Um, anyway, I just called to say hello. Mommy and me had pizza tonight and I hope you’re having a good time wherever you are. Bye-bye!”

It was like hearing music after a lifetime of being deaf. He had sent Rafe a bunch of stuff over the past two weeks — tapes of him reading stories from the Brothers Grimm — Rapunzel, Hansel & Gretel, The Fisherman and His Wife; a boxed set of musical sound tracks; a photo of himself from the Cincinnati sports pages; a postcard from the Pittsburgh zoo that showed a Kodiak Bear tossing a ball with his nose at some spectators. He had also sent a telephone debit card, a copy of the Red’s remaining schedule with his custody days circled, and the phone numbers where he could be reached. This was the first opportunity Rafe had to use the new system, and he’d pulled it off like a pro.

He pressed 1 and listened again. “Hi Daddy, it’s me, Rafe … ” His voice felt as close and reassuring as a hug. Jason played the message a third and fourth time, then saved it to listen to later.

“I hope you’re having a good time wherever you are. Bye-bye!”

VICKI YANKED down the front of Rafe’s white vest until the wrinkles vanished, then swiped the cracker crumbs from the corners of his mouth with her plum-colored fingernail. “You look wonderful,” she smiled. She ran her hand down the soft sheen of his cheek. “You look like Mozart.”

Rafe gripped his jaw but he could no longer fight it. His eyes filled with tears, his mouth opened in a silent howl. “Baby, what’s wrong?” Vicki asked with alarm, squatting beside him. It was a cool October night, with a faint stitching of stars above the city. A steady stream of kids, parents and teachers poured through the front doors of Aurora Craverro School of the Arts.

“I don’t want to go,” Rafe cried.

“But baby, your whole class is in there.” She wiped the tears from his cheeks and held his shoulder firmly with her other hand. “You can do this,” she encouraged him. “You know the words.” He shook his head. “Sure you do, we practiced them over and over again.” She flattened his collar, and jerked his red bow tie back and forth. “Let’s just straighten this bow-tie — ”

“It’s a butterfly tie!” he shouted, his eyes sharp with anger now.

“Of course,” she said, softening in the face of what could become a full-blown tantrum. “It is like a butterfly, isn’t it?” She tucked in his shirt and centered his belt buckle. “We should go in now. It sounds like everyone’s getting ready.”

“Daddy said he was going to come.”

“Daddy says a lot of things.” She wiped his cheeks again. “C’mon, this is a happy night. We’ll go to Mitchell’s for ice cream afterwards and celebrate.”

He let her lead him into the crowded auditorium, where the Fifth Grade Orchestra was warming up. The other members of Rafe’s third grade class — or for the purposes of this special evening, Le Troisieme Chorale — had already assembled on the stage, the boys in their white tails and red ties fidgeting and weaving like a field of poppies in the wind, the girls lined up single file in their magenta gowns and matching hair ribbons. He was part of the chorus, singing the original fifth grade composition, “Magic at Hogwarts: The Harry Potter Symphony.” Next year, as a fourth grader, he would be in the orchestra as either a pianist or cellist.

Vicki squeezed his hand and released him up the steps. “Good luck, my sweet.” Rafe took his place in the back line of the chorus, a lost look on his face. He watched his mom linger at the bottom of the steps, then take out her digital camera and turn it towards him.

“Mom!” he whined, trying to wave her away. Suddenly the students began to stir. Rafe’s eyes grew big and a smile lit his face. Vicki turned and there was Jason striding down the side aisle, followed by a young man and young woman pushing hand carts loaded with long cardboard boxes.

Rafe rushed to the edge of the stage. “You came!” he shouted. He had left messages for his father in Chicago and Cincinnati but wasn’t sure he got them. Jason laughed. “Of course I came!” He grabbed Rafe and swung him off the stage. He could see that he’d been crying. “What’s the matter, Buddy?”

Rafe squeezed his father as hard as he could. Jason squeezed back. “That’s OK, Buddy, I’m here,” he whispered.

The familiar discord of an orchestra tuning up signaled the imminence of the program. Jason set Rafe back down on the stage. “Knock ‘em dead, Tiger,” he said, before backing away. There was a buzz in the crowd that Rafe’s father had brought baseball bats signed by Giants’ players. His helpers unpacked the boxes and leaned the bats near the stairway where the performers would be leaving the stage.

Slowly, the house began to quiet. Jason ended up standing along the wall of the packed auditorium directly behind Vicki. “What are you doing here?” she asked, turning to address him but without looking at him.

“What do you think I’m doing here?”

She exhaled loudly, clearly unnerved by his presence literally breathing down her neck. “You’re disrupting everything!”

“Disrupting what? I’m his father!”

“That hasn’t done him a whole lot of good up to now.”

“It’s not for lack of trying.”

The opening strains sounded and the chorus stiffened as if they had been struck by lightning. Rafe watched his parents, his two favorite people in the world, talking together and his smile grew. Maybe they’d have pizza together and watch a movie; maybe his father would come on the school hayride in Sonoma.

“It’s going to be different now,” Jason said into the back of Vicki’s head. Rafe was swaying now in unison with his white-suited classmates, who were gathered like pleats in a semi-circle at the back of the stage. His mouth opened wide as the chorus sang out the opening refrains of the Brahms-inspired overture. “I’ve been traded.”

Vicki turned and looked him in the eyes. A set of violins and goofy flute music erupted from the orchestra, then the boom of a kettle drum and the tinkling of a chime.

“What do you mean?” she asked.

He smiled down at her, clearly gloating. “I’m playing for San Francisco now.”

JASON RENTED a two-bedroom condo along the waterfront near PacBell Park, in a bayside development called South Beach Harbor. There was a big picture window with a view across San Francisco Bay to Oakland, and a swimming pool out the back door shared by the other condos in the complex.

Jason’s first day there with Rafe was one of the happiest in his life. They rode bicycles along the waterfront almost to the Golden Gate Bridge, and when they returned they set to work preparing Rafe’s favorite dinner, spaghetti and meatballs. Side-by-side they stood at the marble-top counter, rolling ground turkey into meatballs on a wooden cutting board. Jason sautéed the meatballs in a large iron skillet while Rafe cut up lettuce, tomatoes and carrots for a salad, his face knotted with concentration.

“You’re quite the chef!” Jason exclaimed.

Rafe smiled up at him. “This is fun!”

When everything was done they sat on opposite sides of the table in the small dining room. “How you doin’, Bud?” Jason asked.

“Good.” Rafe smiled, shoveling a forkful of spaghetti into his mouth. Jason wasn’t sure what else to say. He hadn’t spent time with his son since July, when the Reds played in San Francisco. Rafe was taller, his cheekbones broader, his eyes set deeper in his face. It happened like this every off-season, returning like some general and having to introduce himself anew to his family. This time, however, there was one huge difference: the general had come to stay.

“You got homework tonight?”

“It’s Saturday!” Rafe replied.

“They don’t give homework on weekends?”

“Uh-uh. Weekends are for playing!”

Jason smiled and looked out at the ships lined up in San Francisco Bay. As a boy in Port Sulphur he used to watch oil tankers disappearing over the curve of the sea and dream of sailing away. But no more. He had a contract to play baseball in the town where his son lived. There was no better dream he could have.

After dinner they brushed their teeth in the large, mirrored bathroom, then Jason led Rafe up to his bedroom. He had bought a full-sized double bed for his growing son and covered it with Rafe’s Stanford quilt and a half dozen of his favorite stuffed animals. A small ship’s lamp glowed beside the bed.

Rafe leaped on the quilt and hugged his furry friends. Then he gazed out the window at the blaze of lights in the center of the bay.

“You know what that is?” Jason asked. Rafe shook his head. “That’s Treasure Island.” Rafe’s eyes danced as Jason pulled the covers back for him to slide under the flannel sheets. When he was settled, Jason held up an oversized book.

“Treasure Island!” Rafe shouted. The cover illustration was a giltedged painting of a pirate and his parrot, with a triple-masted schooner looming behind them. Jason balanced himself in the miniature rocking chair beside Rafe’s bed. “Chapter One,” he intoned. “The Old Sea-Dog at the Admiral Benbow.”

He looked down at Rafe. “You ready for this? There’s pirates and stolen treasure and sword fights — it’s pretty rough stuff.”

“They have sword fights in Star Wars,” Rafe said dismissively. “With light savers.”

“Light sabers,” Jason corrected him.

“Light savers,” Rafe insisted. He looked sincerely into his father’s eyes. “It’s all make-believe anyway, Daddy.”

Jason smiled and set the book across his knees so Rafe could see the illustrations as he read. “Squire Trelawney, Dr. Livesy, and the rest of these gentlemen, having asked me to write down the whole particulars about Treasure Island, from the beginning to end, keeping nothing back but the bearings of the island …”

He paused and looked at Rafe, who smiled back at him with warm, sleepy contentment. Jason took his hand and squeezed it. “I’m glad you’re here, Buddy.”

“Read, Daddy!”

Outside, the lights of Treasure Island twinkled in the center of the bay. Jason returned to the book, reading in a firm, animated voice: “ … and go back to the time when my father kept the Admiral Benbow Inn, and the brown old seaman, with the saber cut, first took up his lodging under our roof … ”

IN SAN FRANCISCO, nobody argues with a Giant. Despite Vicki’s objections, the court granted Jason’s request for joint custody on alternating weeks, even during baseball season. Vicki didn’t tell Rafe about it until the end of the week, when he was scheduled to begin his first full week with his father. She picked him up early from aftercare and took him to his favorite restaurant, the Sushi Boat, where food sailed by on little wooden barges along a flume filled with flowing water.

“What’s that? What’s that? What’s that?” Rafe cried excitedly as the sushi floated by. Vicki leaned over and swiped a smear of wasabi from the sleeve of his sweatshirt — Aurora Craverro School: Life Imitating Art. “You know,” she began, her eyes fixed on his face. “Things are going to be different now. The courts have ruled that you have to spend every other week with your father. I won’t see you until next Friday — a whole week away.”

Rafe squeezed a California roll between his chopsticks and brought it carefully to his mouth. “Did you hear what I said, Rafe? Do you know what this means?”

“I spend a week with Daddy and a week with you,” he replied simply.

“You don’t have to do it if you don’t want to. We can ask the court to keep things the way they were.”

“That’s OK,” Rafe said. “I spent a week in Hawaii with Gramma and Grampa.” He watched more sushi boats sailing by with their cargo. He had no idea what most of them were and let them go. Either way, he didn’t want to think of the other stuff. As long as he sat here he could choose whatever he wanted; his mom ate the ones he picked that were too strange to eat. The ones he really liked were the California rolls, cylinders of rice stuffed with cucumbers and avocado and crab, but there hadn’t been any of those for a while.

“That was vacation,” Vicki said. “This will be on school days and music practice days and weekends too.”

Rafe’s attention was focused on a procession of freshly loaded boats listing with gleaming slivers of fish, rice cones overflowing with roe, and octopus arms trailing in the water. Then a boat loaded with a fresh California roll appeared around the bend. He watched anxiously as it sailed past the other diners, then he reached out and grabbed it.

“Don’t you want to try something else?” Vicki asked.

“I like these,” Rafe replied.

JASON WAS pacing the sidewalk when Vicki and Rafe returned to school. He loomed over Vicki’s Acura as soon as she stopped. “It’s my turn to pick him up — I’ve been waiting since quarter-to-six!”

Vicki glanced at her watch. “We went out for dinner,” she said. “What difference does fifteen minutes make?”

Jason yanked open the door of Vicki’s car. “C’mon,” he said to Rafe. “We’re going to be late.” Rafe reached for the little overnight bag he had packed — his Sylvester the Cat travel toothbrush, cable car slippers, a black plastic spider ring, his purple platypus Pillow Buddy. “This arrangement stinks and you know it,” Vicki said as Rafe got into Jason’s jeep. “This is his life, Jason. He’s got off from school on Thursday — do you have plans for him? He’s got music lessons Wednesdays, soccer practice Tuesdays and Thursdays, and play dates worked out for the weekend. You can’t handle that yourself.”

Jason looked at his watch. He had hoped to get to the Oakland Arena by seven and introduce Rafe to some of the Warriors. He had expected Rafe to be here, ready to go, and be well on their way by now. “Compared to having to deal with you, that’s nothing.”

“This isn’t about you and me, Jason. It’s about what’s best for Rafe.”

“That’s right.” Jason pressed forward, seeming to swell with self-righteousness. “Do you know the number one reason for teen pregnancy? Drug use? Depression? It’s not having a father in their lives.”

Vicki stared at him with unmistakable contempt. “He’s not a teenager.”

“You know what I’m talking about.”

“This is too abrupt,” she insisted. “We should do this more gradually … two days on, two off, something like that.”

He’d planned to be magnanimous in victory, but his lips curled with a contemptuous smile. “To quote the immortal words of Vicki Repetto — ‘Tell it to the judge.’”

NEW GIANT A FORCE OFF THE FIELD, TOO

B.A. Najarian, SAN FRANCISCO DAILY

Last fall when the Cincinnati Reds challenged the Cardinals for the divisional playoffs, their MVP in the stretch was former Stanford lefthander JT Thibodeaux. Pitching with the power and precision scouts always predicted, Thibodeaux finished the season with four straight victories and helped bring the overachieving Reds within one game of the postseason. Most players would spend the winter plotting a return to even loftier heights, but Jason Thibodeaux is more than a baseball player.

Thibodeaux is the guy who forewent his senior year at Stanford to raise his son. Actually, he almost forewent his baseball career, overlooked in the draft as a head case rather than a heart case. But Thibodeaux eventually found a home in the Reds’ farm system, where he earned his way to the Show and compiled a 24-27 record in 2+ years for the Reds. The only problem, the kid he had raised was two thousand miles away — in San Francisco. So Thibodeaux did something that no one has asked to do since their pennantwinning team three years ago — he asked to be traded to, not from, San Francisco.

The rebuilding Giants are counting on Thibodeaux’s strong left arm and senior-circuit experience to help put them in contention. Thibodeaux, for his part, is counting on proximity to his eight-year-old son, Raphael, to revive his starring role as a father. “I’m really happy to be with this team,” he said. “But I have to be honest and say that the main reason I’m here is my son.” Thibodeaux’s boy is a third grader at the Aurora Craverro School, a private arts school in the city’s Noe Valley (“Home of baritones and ballerinas,” JT says).

Besides a 98 MPH fastball, JT brings a scholar’s knowledge of NL hitters. As a student of Stanford’s Walt Baptiste, Thibodeaux kept notebooks on every hitter he faced. He applies the same kind of discipline to child-rearing. In a profession where men drop their seeds with the vigor of a full-grown Valley Oak and nurture them with the diligence of werewolves, this Giant is an oddball.

Thibodeaux challenges those in the league who say they spend quality time with their kids. “How many know what their kids’ favorite foods are? Their shoe size? The name of their favorite stuffed animals? That’s the kind of knowledge you only get by putting in the time.”

Maybe the Giants will win more games this season, maybe not. A twelve-game winner with the Reds last year, Thibodeaux most likely will replace twelve-game winner Rick Lambert in the starting rotation. But whatever happens on the field, the number of Giants pulling full-time duty on the homefront just went from zero to one.

THE GIANTS’ facilities were state-of-the art compared to the moldy basement the Reds skulked around in. The selection of new treadmills and Cybex machines, stationery bicycles, Stairmasters and Beaman weights inspired Jason to work out almost as much as his desire to make good in the city that housed his son. Living near PacBell Park, he became a regular at the Giants’ training facilities.

The Monday before Thanksgiving he came in for his workout as usual after dropping Rafe at school. His locker was two spaces away from the famous corner belonging to Isaac Sands, the premier slugger in the National League. Voted Most Valuable Player three times by the sportswriters he publicly disdained, Sands had negotiated an entire corner of the dressing room for himself, comprised of four lockers. The regulation lockers were already luxurious affairs, cherry wood cabinets with two polished shelves, a lock box for valuables, a compartment for street clothes on one side and baseball gear on the other, and a handcarved wooden shoe rack. The dividers in Sands’s lockers had been removed to make room for a CD and DVD tower, a 47-inch television, and a water cooler holding a ten-gallon jug of PowerAde.

Jason was surprised to find Sands himself sitting on his black leather couch, watching what looked like a highlight film of his own exploits, mostly a parade of images of his powerful left-handed stroke pounding balls over walls in various ballparks in rapid strobe-like succession. He was a tall, broad-shouldered man with a full handsome face, and the charisma of someone one hundred percent certain that the millions of people who thought he was the greatest ball player of all time were absolutely correct. He wore black slacks, a black turtleneck sweater, black shoes, a small diamond earring in his left ear, a thick gold-banded watch on his right wrist, and a heavy gold necklace with a crucifix.

Jason changed into Giants sweats, tied on his cross trainers and locked away his wallet and watch. He wasn’t sure what to do. Sands was notoriously uncommunicative, known for his loud home runs and one word answers to the press. But seeing that Sands’s highlight reel was finished, he stopped in front of the couch.

“I’m Jason Thibodeaux,” he announced, sticking out his hand. Whatever he had expected from the slugger, it wasn’t what he got.

“String cheese, Pop-Tarts and artichoke hearts,” Sands said, without looking up.

“Pardon me?”

“Godzilla, Superfly and Lambchop.”

Maybe it was some kind of hazing, gibberish for newcomers particular to the Giants’ clubhouse. “I’m with the team now — I came over from the Reds,” Jason offered.

“I know who you are,” Sands said. “You’re the guy who says I don’t know my kids’ favorite food. Or the names of my kids’ animals.”

Jason stared, mouth open. “The morning paper,” Sands said. “Read it and weep.”

It wasn’t difficult to find Najarian’s column. Someone had posted it on the bulletin board outside the manager’s office. He had let B.A. Najarian spend a morning watching him work out, talking about the trade, his pitching philosophy, his custody struggles. But he was mortified when he read the article. It was hard enough being traded to a new team. Loyalties and affection that get built up only through combat have not yet been formed. And most guys are traded to fill some need of the team — replace an injured player, help the team meet the salary cap, rebuild for the future, back up a valuable veteran — rather than the needs of the player. He was a less-than-.500 pitcher with a reputation for flakiness — and now this.

Jason pushed through the double doors and up the ramp to the field. It was a soft sunny day, a Northern California autumn classic. He did a series of warmup stretches and ran two perimeters of the field, then more stretches and windsprints across the outfield before heading back to the weight room. Sands was there, jerking and pressing unimaginable amounts of weights. Jason went through his own regimen, self-consciously adding plates to his normal amounts but acutely aware that he was lifting nothing close to Sands’s limit. There were a couple of other guys there as well — Darryl Brooks, a backup second basemen, and Felipe Colon, a centerfielder trying to make his way back from shoulder surgery. No one said a word to him.

After an hour, he made his move. He found Sands between reps, hunched forward on a bench, rolling his shoulders like locomotive wheels.

“As lame as it sounds,” Jason said, “I was misquoted.”

Sands didn’t look at him. “If you don’t talk, they can’t misquote you.”

Jason chuckled. “I’ll remember that.” He paused. “I admire what you’re trying to do — what you’re doing with your kids.” Jason, along with the rest of the world, knew that Sands was going through a bitter divorce and custody battle involving his two daughters, eight and five, and his three-and-a-half-year-old son, as well as the most judicious way to divide up his six-year, $160 million contract. In an argument over money, Sands had pushed his estranged wife and called her a whore in front of their children. It cost him more than six months away from his kids, mandatory enrollment in an anger-management class and the opprobrium of millions. He had completed the twenty-six week anger-management class and now was awaiting the court to assign a custody plan.

Sands rose from the bench. He was an inch shorter than Jason, but by his bulk and sheer power of presence seemed a foot taller. He grasped Jason’s hand in an old-fashioned soul grip, pulling him closer. “I admire what you’re doing, man. You are the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria.”

Jason was shocked. Sands continued to hold his hand, staring into his eyes. “You got a kid whose favorite food is artichoke hearts?” Jason finally asked.

“My boy eats them like potato chips,” Sands grinned, dropping Jason’s hand. “He calls them okes. ‘Okes, okes, okes,’” Sands said in a baby voice as he strutted back to a set of weights that Jason estimated at 340 pounds. “He eats any kind of vegetable.” Sands lay on his back and grasped the bar. “If it’s green,” he said, pushing the massive weights above his head, “it’s good.”

Jason smiled knowingly. “My kid loves salad.”

“Salad is cool,” Sands grunted, lowering the weights. He gathered himself, then pushed the weights up again. “But mostly my kids love baseball.”

After Sands broke the ice, the other guys started talking. It was baseball now, and nutrition, who was playing winter ball, who was hurt, who was a comer. Sands held court in the weight room for nearly two hours, quietly sharing insights about pitchers in their division, what they threw, how to beat them. At two o’clock, Jason lowered his last weight. “I’ve got to pick up my kid at school,” he announced.

“You do that,” Sands said. “Tell him Isaac Sands says hello.”

Jason grabbed a falafel from Tunisia at 20th and Valencia and double-parked his Jeep behind the row of SUVs and foreign luxury cars outside Rafe’s school. He sat at the wheel wolfing down the sandwich, wondering what to fix Rafe for dinner. He had wanted to take him to the library but there were so many other things to do. Rafe needed new shoes and underwear, and his hair was out of control. Vicki was leaving more and more of these things for his weeks with Rafe. Fathering wasn’t just Saturdays at Waterworld or a weekend in Disneyland anymore. It was a week-long job, showing up every day at the schoolhouse door, fixing dinner and cleaning up, helping Rafe with homework, drawing a bath, herding him to bed, reading a story, tucking his tired body beneath the blankets, giving that last hug, the last back scratch, the last reassuring word. But all that was fine, really. It took Jason back to the year he cared for Rafe when he was a toddler. What he was having trouble with was Rafe’s total indifference, even hostility, towards baseball.