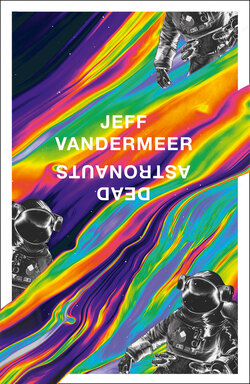

Читать книгу Dead Astronauts - Jeff VanderMeer - Страница 10

ii.

Оглавлениеthey needed no fire

for the fire burned

within all of them

Chen could see bits and pieces of the future, “but only in equations.” A frequent lament. Numbers could attack the flesh, the will, but rarely built it up. Morale for them never lay in the numbers. He made poetry out of his premonitions, his equations, because they’d proven useless to him as fact, because he was never sure whether he was actually seeing the past. A past.

Chen liked to play the piano and to down a hearty meal with a beer. Meals because he spent prodigious energy keeping his form. The piano because it made him remember to be careful—how watchful he must be of his own thick fingers. Or this is what he said, “It makes me limber-er,” when mostly it was a link to his history. Or what had been implanted in him as history.

There had been little enough of either lately. Pianos and hearty meals. He must take his sustenance from the molecules of the air with which he often felt interchangeable, and he compared notes with Moss, because their moves through fluid states were similar, even if his was a kind of fight against evaporation or ejection and hers an overabundance of accretion, a building up.

Flesh was quantum. Flesh was contaminated, body and mind.

Chen dealt in probabilities on one side of his brain and impossibilities on the other. Because the probability was always that he would disintegrate into his constituent parts sooner rather than later. He had come to think of himself as a complex equation and a symphony both, and, really, what was the difference?

The equation of the Company eluded Chen, perhaps because he had been lost within it once upon a time. Or as he said sometimes, the system abhors source, makes its mapping into a maze, a mockery, and the more you think you understand it, the more you are colonized by it. And lost.

As they walked, suspicious of the shadows within every husked building:

“It was never real.”

“It was real.” Chen or Moss, it didn’t matter.

“Not real in the sense of lasting.”

“Nothing is real, then.”

“Real enough.”

Real enough was the anchor that kept them from falling apart. Through all the versions.

The glowing star of Chen’s hand had begun to burn before the drift, so that it did not plummet but, light, hollowed out, it caressed the air as ash in hand-form, disintegrated before it could reach the ground. Almost as if the hand could not believe in its own engineering. He would grow another by morning.

Yet still he felt the hand as it floated, as it drifted, as it became nothing. Loved the weight and certainty of that dissolution.

The hand laid bare the one who had created it, along with Moss: Charlie X, whom Chen thought of as the missing fourth member of their party. Vain hope. Nothing across the versions to support it. Nothing that could have registered on Grayson’s radar, just in the form of a bullet she would like delivered to Charlie X’s brain. Even though it was too late.

Charlie X was on some part of the blackboard that had been smudged and no one could solve the equation now. Just knew the original answer had been incorrect.

“What’s my point?”

“Are you losing your point?”

“Your point is your defense.”

“I still have three points to use.”

Were they all losing the point along the way?

If so, Moss least of all because she didn’t have the luxury. She was the map, the way in and the way out, the leader of the heist and its blueprint.

Chen’s equation was a wall of circles with plus signs between them, and then some basic geometry that proved he was more than the sum of his parts. Held together by math.

But Moss? Messier. Moss liked, well, moss—and lichen and limpets and sea salt and the beach and guessing the geological scale of things. And strawberries—she loved strawberries now that there were none anywhere they went. Also, Moss liked to rescue whatever animal or plant needed it. She believed they had earned it.

Moss lived based on a kind of crime that Chen had witnessed part of but neither had shared with Grayson, as if it were a wound that would bleed out if offered up. Moss kept that wall high and inviolate; for someone who shared herself so utterly, how could Grayson begrudge this one withhold?

Yet sometimes, Grayson’s bad/good eye gleaned hints, the eye so exposed to the alien that it had shut down and opened up, both. Grayson’s eye saw: Moss through a swirl of snowflakes, emerging from a tunnel, emerging from a burning shed, as if she leaked memories without her knowledge. Or was this something she projected onto her? How to make sense of that?

For Chen, Moss was a wall of circles or zeros tumbling over one another, and from each a different Moss peered out. That kept being divided by themselves until there was no room for the rest of the equation and the parentheses grew into vines and cracked the blackboard and made math into something that could never be solved. While Moss escaped through one of the circles. For Moss could bud another Moss off her big toe if she liked—as she was fond of saying.

Chen had been beholden to Moss’s kindness, in ways Grayson would never understand. You had to be there. You couldn’t conceive. Empathy wasn’t enough. Imagination wasn’t enough.

By contrast, Grayson was a single circle from which radiated calculations like the sun’s rays and a latticework of numbers between each ray. She liked to be as direct as a fist to the face. She had survived that way out in space for so many years that there was no other solution for her. She knew the stakes of their mission because she’d had so few choices before Chen, before Moss. Chen tried not to diagram her or turn her into poetry, even though it was in his nature. Did not want to solve her, for fear she’d tumble like Moss’s zeros, but, not used to it, shudder apart, disintegrate. No matter the grim set of her jaw.

Chen, Moss, Grayson. They each only used one name now. Had been winnowed down, become too familiar, had not the need nor the want for the territory of two names. When encamped, they lay heedless and seamless huddled all three together. Hard to pry apart for the comfort of it, the touch of another. They needed no fire, for the fire burned within, warmed them even in the deepest cold. And the source was Moss.

“Good night, Moss.”

“Good night, Chen, Grayson.”

Just a mutter from Grayson, but they knew she loved them.

Each had had the experience of self-annihilation. Chen had killed Chen. Moss had absorbed Moss. Grayson had killed them both. Moss had killed Chen, Chen Moss. Thus their intimacy had become exponential, along with their sadness and their regret. And it was cocooned within that, that they lay together, so close, to treasure the Chen, the Moss, the Grayson, that still lived.

While all three could feel the duck with the broken wing watching over them from afar. For better or worse.

The dark bird.