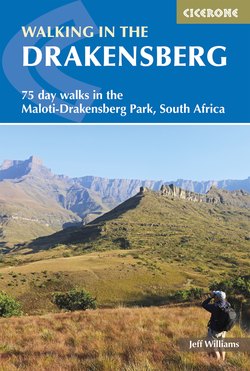

Читать книгу Walking in the Drakensberg - Jeff Williams - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

‘The Boer and his son gazed up at the massive, seemingly vertical, rock wall of the peak above them, the top shrouded in cloud as all the peaks were that day. High above they saw clearly a giant lizard with a long tail and wings flying easily across the sky. They called the mountains in their Afrikaaner language the Drakensberg – the Dragon’s mountains.’

So goes the story, however implausible. In reality the precise origin of the name is unknown but it dates from the early 19th century. In the Zulu language it is called, equally graphically, uKhahlamba – the Barrier of Spears.

It is a land of spectacular natural beauty; an extraordinary mountain range of huge peaks, towering basalt cliffs, massive sandstone outcrops, deep gorges and crystal-clear mountain streams. There is a good chance of seeing a variety of antelope and the area has a regular bird list of well over 200 species.

Add to this the fascinating history exemplified by the Bushman rock paintings spread widely across the whole area, together with its unique geological structure, and you can understand why it has been designated a World Heritage Site.

The Amphitheatre in the Royal Natal National Park seen from Thendele camp with the Sentinel on the right.

The remote, high valley at Engagement Cave (Walk 69)

Geography

The Drakensberg mountains, which stretch from Cape Province up to Eastern Mpumalanga province, are the massive outer rim of the escarpment of the great interior plateau which is a major and climatically important feature of South Africa’s topography. The Maloti-Drakensberg Park forms a crescent-shaped area 200km long, perched on the eastern border of Lesotho and stretching from the Royal Natal National Park (RNNP) in the north to the Sehlathebe NP of Lesotho in the south.

The escarpment itself and the plateau beyond are generally known as the High Berg, perhaps most famous for the 4km-wide sheer basalt wall of the Amphitheatre in the RNNP. The plateau has an average height of approximately 2900m, but numerous peaks reach much loftier altitudes. The highest point is the peak called Thaba Ntlenyama, lying inside Lesotho and at 3482m the highest point in Africa south of Kilimanjaro. There are many sheer rock walls of 500m or more. Below the High Berg is an area of numerous, lower, grass-covered mountains and smaller hills, known as the Little Berg, with its steep-sided spurs and valleys. The line of sandstone cliffs and outcrops that runs the entire length of the Drakensberg is a conspicuous feature and divides the Little Berg from the lower valleys.

Geology

Experts claim that the geology of the Drakensberg is ‘simple’. Although that might well be the case for some people, less geologically aware souls such as the author struggle with the complexities of the subject. Fortunately even a basic understanding of the local geological history does a great deal to make the stunning scenery fall into historical perspective and adds to the pleasure of the walks.

From 250 to 300 million years ago the whole area was a vast expanse of shallow lakes, alluvial flats and swamps sitting on a large land-mass known as the super-continent of Gondwana: essentially today’s Africa, South America, Antarctica, Australia and India. Flowing water separates particulate material according to size, so when gravel, sand, silt and mud were carried into the lake they were deposited in different places and layers upon underlying granite. This process, called sedimentation, continued over millions of years, and the weight of continuing deposits served to compact each underlying layer. This compaction formed what are known, unsurprisingly, as ‘sedimentary rocks’. For example, sand accumulations are converted into a sedimentary rock called sandstone, mud into mudstone (also called shale) and so on, although the names are not usually quite so obvious.

The lowest and therefore oldest layers that can be seen readily in the Drakensberg are those of the Molteno Formation, successive beds of sandstone alternating with layers of blue and grey mudstones. They often present a sparkling appearance because of the minute quartz crystals that bind together with sand particles. The most easily seen example is at Mermaid Pool in the Garden Castle area (see Walk 73).

The Elliot Formation, originally called ‘Red Beds’ because of the iron oxide content, has alternating layers of red mudstone and fine-grained sandstone. These are extensively exposed on the hillsides of the Drakensberg foothills and, when non-weathered, exhibit their characteristic dark red colouration.

An outcrop of Clarens sandstone above the red-coloured Elliot Formation in Sleeping Beauty valley (Walk 69)

Towards the end of this phase of sedimentation there was an increase in warming and aridity to produce desert conditions. The whole of today’s South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia became a vast sea of sand. The deposition that occurred at this time was wind rather than water-driven and these deposits formed the Clarens Formation. These huge sandstone cliffs cap many of the Drakensberg foothills, or Little Berg. They are often seen weathered into extraordinary shapes, a good example being Mushroom Rock in the Cathedral Peak area. In simple terms, winds have swirled across the rock face and picked up sand and other particles which, in turn, have worn the cliff or rock away by an abrasive effect, forming caves.

This process is accentuated by surface water seeping down into cracks and subsequently freezing, thereby widening the cracks. The more this occurs, the more the likelihood of chunks of rock falling off as part of the erosion process, thus creating the beautiful and sometimes weird shapes seen in sandstone all over the area. Most of the caves in the area are found in this formation. The use of the word ‘cave’ is interesting: they are almost never true caves, more large overhangs.

For unknown reasons this period of sedimentation came to an abrupt end about 150 million years ago and subsequently the tectonic plates of Gondwana started to drift apart. As well as breaking up Gondwana into the constituent continents that we recognise today, this stretched the plates and caused molten rock (magma) to burst through to the surface through a complex series of fissures or fractures in the earth’s crust. The result was a succession of dramatic floods of basalt lava covering almost the whole of southern Africa. This gave rise to the layered appearance seen today, with individual lava flows of up to 20m in thickness.

In the area of the Drakensberg this solidified to a depth of at least 1000m especially over what is now Lesotho. The height of the cliffs and exposed steep slopes allowed subsequent weathering and erosion to bite into the margin of the lava plateau so that the broken material accumulated as an apron of rubble at the foot of the escarpment. In fact, of the extensive lava sheet that originally covered South Africa there are few such volcanic rock areas remaining in the region. The Drakensberg is probably the best place to see them and it is important to remember that the spectacular shapes of the peaks and rock formations are more the result of the later erosion by wind and water than by the original volcanic uplift. Generally, basalt cliffs are friable and make a poor playground for rock-climbers.

Basalt wall in the Sani Pass

Mammals

There are 48 mammals recorded as living in the Drakensberg. Realistically you will see very few of them and if your aim is to see lots of mammals then you should plan on visiting a game reserve. But there is a good chance of seeing baboons, some antelope and dassies.

The Chacma sub-species of the Savanna Baboon

After man the baboon is the largest primate in southern Africa. Although very tolerant of different habitats they require cliffs or tall trees as a night-time refuge and must be near water. They are very gregarious and live in troops of anything from a dozen or so to a hundred or more. They are extremely vocal and it is baboons that are responsible for the angry barking that you will hear when walking in almost any area of the Drakensberg. You may find places where small rocks have been moved or overturned. This is a sign of baboons searching for invertebrates. You will also find shallow scrapings where they have looked for roots. Never feed them, never chase them and never corner them: they can be vicious. If they become habituated to feeding the Park Rangers will shoot them.

Antelope

Eland, Mountain Reedbuck, Grey Rhebok, Common Reedbuck, Oribi, Bushbuck, Blesbok, and Common Duiker are amongst the antelope that you may encounter in the Drakensberg. Of these, the first three are the most commonly seen.

Eland are the largest African antelope and occur naturally in the Drakensberg, the only place in southern South Africa where this is the case. Males may weigh up to 900kg, and although they are huge they can jump remarkable heights, easily clearing a 2m fence from a standing start. The herds are often large, 25 or more, but solitary animals and pairs are seen frequently.

The smaller your party and the less noise it makes, the better your chance of a good sighting. Very early in the morning is always the best time. As an aid to identification there are a number of books available with good photographs and clear descriptions.

Rock Dassie (Rock Hyrax)

Dassies look like rodents but are not. They are yellow-fawn in colour with paler underparts. Dassies are quite sociable and live in groups of up to about 40, they are rock dwellers and usually active after sunrise when they graze or browse. Their main predators are eagles. A giveaway sign of their dwellings is a white and brown streaked rock wall below the residence which is caused by the tidy disposal of ‘waste’ outside the hole.

Black-backed Jackal

The jackal is a canid (dog), widely seen across southern Africa and has a well demarcated black back flecked with white. The tail is black and bushy. They can be seen by day in reserves or other protected areas but are much more wary and nocturnal when threatened by the presence of man. They are usually seen as one of a pair or solitary. Their diet is very flexible and ranges from small or baby antelope, birds and rodents right down to berries and fruit. Jackals will kill goats, sheep or calves when the opportunity arises. Understandably this antagonises the farming community who, with good reason, regard them as pests.

Blesbok

Eland at Stromness Hill (Walk 65)

Feeding the baboons can have adverse consequences

A watchful baboon

Eland at Jacob’s Ladder (Walk 53)

Rock dassies also climb trees

Leopard

This magnificent animal is uncommon but widely distributed in the Drakensberg. It is rarely seen: not for nothing is it described as ‘the Prince of Stealth’. Powerfully built and amazingly catholic in its dietary habits, it lives in woodland and rocky outcrops and is included here because it is the only large predator in the Park. It poses no risk to walkers.

Although not in the cat family, it is of interest that both spotted and brown hyaena have been captured recently on camera traps but sightings are very rare.

Snakes

There are a lot of snakes in Africa, some 170 species in southern Africa alone. However, tourists rarely see one and, if they do, it is unlikely to be venomous. More people in South Africa are killed by lightning than by snakes. The Berg does have its share of snakes and it is prudent to know something about them, in particular, what to do in the highly unlikely event of an ‘incident’. Visitors in the high summer months of December, January and February are the most likely to see a snake. By April they are preparing to hibernate and so may still be moving around looking for that last precious calorie for storage. It is more unusual to see one in May but by September they’re back.

The three snakes described here are the only significantly venomous ones you might encounter.

Puff Adder (Bitis arietans)

Most snakes detect your approach by their highly-developed vibratory sense and make their escape before you see them. One exception is the Puff Adder, a slow-moving and bad-tempered piece of work who likes to bask in the sun and freezes rather than moving away, anticipating that excellent camouflage will save the day. It is a stout snake, yellow-brown in colour with black chevrons and a triangular head quite distinct from the body, some 90cm in length on average but sometimes much longer. Its venom is very potent and cytotoxic (cell destroying), and envenomation is serious. Death is rare but the bite, from the snake’s very large fangs, is hugely painful and tissue damage may occur, often severe enough to require grafting or even the loss of part of a limb. This snake is responsible for about 60 per cent of all serious snake bites in South Africa. It is rarely found above 2000m altitude.

Puff Adder

Berg Adder (Bitis atropos)

As the name suggests this is predominantly found on high-altitude rocky slopes and mountain grassland and is the most common Drakensberg snake. It is similar in appearance to the Puff Adder but less brightly coloured, without the chevrons, and much smaller, averaging 30cm and sometimes just 10–20cm. As bad-tempered as the Puff Adder, possibly even more so, it hisses loudly and strikes readily but tends to seek refuge much more quickly. Unusually for an adder it has a mildly neurotoxic venom (that is, affecting the nervous system) and specifically has an effect on the nerves controlling the muscles of the face and tongue. This manifests itself as drooping eyelids, double vision, dizziness and sometimes difficulty in swallowing. This is all very alarming but no deaths have been reported.

Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus)

This is a bigger snake than the previous three, averaging more than 1m in length and similar to a cobra in appearance (but it isn’t one), spreading a ‘hood’ when threatened. In the Drakensberg it is often banded black and yellow or black and deep orange, with two or three distinct white bars on its chest only seen when it raises itself vertically from the ground which it does as a defensive posture. This is a scary moment. However, generally it tries to escape when disturbed. Like most cobras it has neurotoxic venom and its bite must be considered serious.

It is unusual in two respects. Firstly it is a ‘spitting’ snake and can project venom for up to 3m very accurately towards the eyes. This is only harmful if it actually gets into the eyes (see ‘Immediate Action’ box, below). Secondly, it has a defensive tactic of playing dead (thanatosis), mouth often open with tongue hanging out. Don’t be fooled: it can be very convincing. Move away and never pick up apparently deceased serpents.

Rinkhals – a spitting snake

Birds

The Drakensberg has an extensive bird list, often quoted as over 300 species. However, this includes vagrants and some birds that are only very rarely seen. Realistically, if any visitor ticks more than 200 species in the Drakensberg then she or he is doing well. For committed birders there are a number of ‘Drakensberg specials’, that is, species that are more easily seen here than elsewhere. At lower altitudes you will see a lot of birds wherever you walk, but fewer in autumn and winter than in spring and summer.

Apart from the ubiquitous Cape Sparrows and Southern Grey-headed Sparrows you will see particularly Greater Double-collared Sunbirds, Red-winged Starlings, Cape White-eyes, White-necked Ravens, Hadeda Ibis and various doves almost everywhere. Many will find a bird identification book indispensable.

Bearded Vulture

Originally known as the Lammergeier, this is the most famous bird of the Drakensberg. There may only be 60 breeding pairs remaining. Here and neighbouring Lesotho are the only sites in South Africa where it can be seen.

If you’re close the identification is straightforward. The black wings, orange-brown neck, underparts and legs, yellow eyes and red eye-ring are characteristic. The ‘beard’ is more of a black, drooping feathered moustache. In flight from underneath note the rich orange-brown underparts, black pointed wings and long, black, wedge-shaped tail. The birds feed on carrion which they drop repeatedly from a height onto rocks to break up the bones with their constituent marrow.

This is a great and rare bird to see. A major conservation effort sponsored by KZN Wildlife is in place, which encourages observers to report sightings. (A copy of their promotional poster is reproduced with their permission on page 24.)

The frequently seen Greater Double-collared Sunbird

The endangered Bearded Vulture

Jackal Buzzard on the Sani Pass

The South African endemic Ground Woodpecker living up to its name

The habitats

Glossy Berg Bottlebrush (Greyia sutherlandii) – a small tree with beautiful flowers on high rocky slopes

Fortunately, most of the original Drakensberg habitat hasn’t changed significantly over the years, except in respect of the composition of some of the grassland. What you see today is to a large extent what was there a long time ago.

Grassland, rich in flowering plants, accounts for more than half of the area. This is important in the maintenance of a stable population of antelope, and for the birds, large and small, who favour this habitat. Their specific distribution is dictated by the height of the grass, so diversity is crucial.

Patches of woodland, including scrub, are scattered throughout, especially, but not invariably, close to watercourses. There is little grass within woodland, which reduces the risk of fire damage. This is also a bird-rich environment. The wooded areas as well as the cliffs are the domain of the troops of Savanna Baboons which every walker will see or at least hear.

Gurney’s Sugarbird

The Drakensberg is studded with streams, but there are no true wetlands because of the excellent drainage of the steep ground. Streams are usually fast-flowing because of the gradient, with pools, waterfalls and steep rock walls. Some specialised flora cling precariously to these walls and flourish there. This is the home of the Cape Clawless Otter, the Drakensberg being its best-known territory. You may notice its scat, studded with white crustacean shell fragments, but to see the animal itself a dawn start and some luck are required.

Wild Dagga (Leonotis leonurus), much-favoured by Malachite sunbirds

Everywhere you look you see rocky outcrops. Where they occur on grassland slopes they make for a small ecosystem of their own. They act as a safe haven for a number of specialist plants. The widespread Rock Dassie lives here and it is the haunt of some specialised birds, including the Ground Woodpecker. At higher altitudes you may see the colourful and endemic Drakensberg Crag Lizard sunning itself on warm boulders.

Some visitors are disappointed in the Drakensberg when they visit in spring and do not see it alive with colourful flowers. This is particularly true if they compare it with the magnificent floral wealth of, say, the Western Cape. But the Drakensberg is almost unique in its geology, site and particularly altitude, which makes for difficult comparisons. Also, the area is dominated by extensive grassland and flowers are often difficult to see. Nevertheless, the altitude rises from 1280m to almost 3500m so there is an opportunity to see a rich variety of plant life. With well over 2000 species of plants recorded, over 300 of which are endemic to the area, it is not exactly a desert.

The hallmark genus of the Drakensberg for many tourists is the Protea with its six local species. There can be no finer sight than a mountain hillside covered with flowering Protea. The Common Tree Fern (Cyathea dregei) is relatively easy to see in many areas, but in others it has become extinct after being extensively pillaged for planting in gardens. It is now protected by law. Up to 5m in height with a crown of arching fronds, it tends to be found in full sun, especially in gullies with a stream close by.

Fire as an ecological tool

When walking in the Drakensberg you will frequently come across areas of burnt grassland. It can look awful. There are three principal causes of fire: lightning, arson and planned burns.

The use of fire in grassland management is long-established and, when used appropriately, of proven scientific value. It removes dead organic material in the winter (the dry season) and prevents or removes encroachment by undesirable plants. In the Drakensberg the main aim is to maintain or develop grass cover for soil and water conservation. Firebreak creation is an important concomitant strategy for limiting the spread of natural or deliberate fires. The creation of firebreaks is a skilled business needing much care and a lot of tough work. Indeed, originally it was done with a hoe!

A firebreak seen from the summit of Sterkhorn (Walk 32)

Major planned grass burn at Cobham

GETTING CLEAR OF A FIRE

In the unlikely event of encountering such a fire at close quarters (a very alarming experience) remember that you cannot outrun it. There may be a stream or other watery haven close at hand. But if a fire comes towards you and escape looks difficult, light the grass around you and follow the line of flames downwind so that you are in a ‘grass-free zone’. If you can control the fire so much the better but it may be impossible. Always carry a box of matches or a lighter in the dry season.

These burns are usually carried out on a two or three-year cyclical basis. When walking in April to June or early July it is important to check where planned burns are taking place and stay clear of these areas. The information should be available at the KZNW local office.

What are the risks to plants and animals? Fire rarely kills trees, grass growth is enhanced and some plants, for example Protea caffra, require the smoke to stimulate dormant seeds. Bigger animals can make good their escape and most smaller ones survive in burrows. Some insects succumb but then act as a food supply for birds.

Bushman paintings

The first evidence of human occupation of the Drakensberg Park area dates back to the Middle Stone Age, some 20,000 years ago. The Bushmen (or San people) were classical hunter-gatherers and decorated caves or rock overhangs with paintings now sometimes known as rock art. They did not necessarily use these places as habitation. The practice started at least 2000 years ago and finished when the last of them had disappeared in the 20th century, mostly by deliberate pursuit and murder. It is said that there are about 20,000 individual rock paintings and engravings spread over more than 500 sites of caves and overhangs.

Important examples have been declared as national monuments including Giant’s Castle Main Caves, Game Pass shelter in the Kamberg Nature Reserve and Battle Cave in the Injisuthi valley. These centres offer guided walks to paintings. The Kamberg Reserve also has a good Interpretation Centre as does Didima camp at Cathedral Peak. There are many other sites of fine quality that have not been so honoured and some, notably those in the Didima valley, are currently closed to the public.

Some paintings are monochromatic but others use two colours or more and are very realistic. The colours used tend to be limited to red, brown, yellow, black and white because of the available materials. Paintings in black and white are more likely to have deteriorated or disappeared, so most of those remaining are of the yellow–red–brown spectrum. Binding substances were required to blend the colours and the whole process was exceedingly complex. Bones, sticks or fingers were used to apply the paints.

The hugely significant Rosetta Panel at Game Pass Shelter, showing a dying Eland with a therianthrope (half human/half animal) holding its tail

The ideas behind this art are more complex than hitherto imagined. Originally it was assumed that the paintings were a simple representation of lifestyle and life events. More recently it has been proposed that much of the art had a spiritual implication, particularly as many depict half-man, half-animal figures. The artists might be both paying homage to animals on which their life depended (such as Eland, the most commonly depicted) and attempting, through art, to harness their power. Nevertheless, it is clear that historical narration also played a part, with some of the paintings, showing wagons drawn by oxen and men on horseback, clearly relating to the arrival of white settlers in the area.

During a trance shamans had an altered state of consciousness and experienced sensations such as an extended scalp or spiritual energy leaving their heads

This could be interpreted literally as people running away from a leopard, or as imagery – the leopard is often associated with shamans, intermediaries between the human and the spirit world

The work was accomplished by certain key individuals, the ‘Shamans’, rather than all members of a social group. These individuals bridged the chasm between the spiritual and the real world. Trance, possibly induced by hallucinogenics on occasion, was important prior to completion.

There are several threats to the rock art of the Drakensberg. The principal ones are natural weathering of the paint (and of the rock) and, sadly, vandalism. The rock shelters were originally created by the process of weathering and it is just a continuation of this process that is causing the damage. How this might be reduced is the subject of much research. Fires lit by people camping in the shelters have created smoke damage and some visitors have even wet the paintings to improve the colours – if they used carbonated drinks to do this the damage is even more significant. A number of initiatives have been taken including forbidding camping in painted caves, fencing some areas off and eliminating the marking of caves on maps.

Access to Bushman painting sites is permitted only if accompanied by one of the widely available qualified and registered guides. I have been advised that it would be imprudent to define exactly the location of where paintings can be seen on routes in this book except where it is clearly a walk to a formally guided site. Nevertheless, when walking in any of the areas, especially in the southern Drakensberg, be alert for that moment when your route takes you slap bang into some paintings. Look particularly at the walls of large overhangs. If you chance upon some paintings be sure to treat them reverently and touch them not.

The Development of the Park

The history of the Drakensberg Park goes back a long way. In October 1903 the Natal Colony government took the first step towards its establishment with a Government Notice which stated its intention to create a ‘game reserve on the Crown land in the vicinity of Giant’s Castle’. Next came the establishment of the Natal National Park in 1916, the prefix ‘Royal’ being added after a visit by the British Royal family in 1947. Gradually more and more areas were designated as protected by the purchase of farmland and by the late 1960s the park was more or less what it is today. Altogether it comprises 242,813 hectares (almost 2500km2) and is the largest mountain wilderness area in Africa. The official title ‘the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Park’ was introduced in 2000, but for brevity the terms ‘the Drakensberg’, ‘the Park’, and ‘the Berg’ will be used interchangeably throughout this book.

More recently, the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Park has been subsumed within the Maloti-Drakensberg Transboundary World Heritage Site, amalgamating with the Sehlathabe NP of Lesotho. Accordingly, the Drakensberg Parks are now labelled with the name ‘Maloti-Drakensberg Park’ and this is used thoughout the book.

Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife (EZKZNW, commonly referred to as KZN Wildlife or KZNW) is the conservation management agency in the province of KwaZulu-Natal and is responsible for the South African part of the enlarged Park.

Subsistence farming community outside Lotheni

Apart from its headline roles of assuring sustainable use of the Park’s biodiversity and wildlife conservation, KZN Wildlife has a pivotal role in the development of ecotourism. The Drakensberg Park is almost entirely surrounded by farmland. There are large cattle farms but local community subsistence farming predominates. Amongst these local communities there is significant unemployment. Ecotourism carries with it the responsibility of involving these communities.

KZNW has created many jobs, particularly through its participation in the ‘Work for Water’ scheme introduced in 1995. It is well known that trees deplete the water supply, and when these trees are alien plants (Black Wattle – Acacia mearnsii, and species of Eucalyptus, especially E saligna, are a particular problem) the pressure to remove them becomes intense. The Work for Water initiative has vigorously addressed this problem and at the same time helped to alleviate some of the poverty. Tourism plays its part in increasing employment by the opening of camps and hotels, and also provides opportunities for Community Guides. These are local people trained to guide walks and, most importantly, conduct visitors to sites of Bushman paintings.

Finally, it is important to mention KZNW involvement, in co-operation with the South African Police Service, in anti-smuggling operations to interrupt the marijuana (locally known as ‘dagga’) trade from Lesotho.

While tourism has always been encouraged and is now an important part of the economic development of communities bordering the Park, it would be wrong to underestimate the problems that ensue. These include resort development and its knock-on effects and, sadly, physical damage to cave paintings. Examples of future development might include cable cars, hotels on the plateau and skiing as well as the ever-present threat of private housing schemes. Walkers will not see this as advantageous and there is certainly a lobby that feels that this will put unreasonable pressure on an already vulnerable ecosystem. Personally, my recommendation is to visit the Park before further significant development takes place, however eco-friendly that might be.

An armed KZNW Ranger on patrol

About the walks

It should be said at the outset that no walks in the Drakensberg Park should be underestimated. The unpredictability of the weather is legendary and the terrain often difficult. Local advice is available and should be sought if there is any doubt about the feasibility of a particular route for your party.

The walks described here are grouped by geographical area from north to south. Each geographical section of the Drakensberg seems to have its own character, a certain ‘feel’ as you arrive, but it is a difficult concept to describe. So, although the Park is often and reasonably heralded as a single entity based on the obvious topographical features of the escarpment and the Little Berg, each part is in reality quite different from the next, with its own unique flavour and attraction.

The Contour Path is an important concept to grasp. It is, more or less, what it sounds like; a path following the contour as best it can across the whole of the area under discussion. Presently it runs almost completely from the Cathedral Peak area right down to Bushman’s Nek at the extreme south of the Drakensberg Park. But, and it is a big but, anyone who thinks that this infers a nice level path which is invariably easy to follow should think again. It is often extremely undulating, can be very rough underfoot and, on occasion, tricky to follow. Nevertheless, it does have a useful, sometimes pivotal, link role when creating round-trip daylong walks and is also a handy tool in route description.

Sleeping Beauty Valley – Magnificent Valley leads off to the right (Walk 69)

By virtue of their inclusion in this book all the walks are recommended. What makes one route better than another? Inevitably it is in the eye of the beholder and involves a number of parameters including scenery, botanical interest, bird life, rivers to play in and many other factors; often it is not even precisely definable. So, personal preferences notwithstanding, there’s no star system or similar here.

Route selection

All guidebooks have limitations of space. This means that route selection is inevitable and some areas with good potential for walking may need to be excluded completely. Mnweni is an inhabited grazing and farming area which is not within the Park proper, lying immediately south of the RNNP. Although some aspects of the area are certainly improving, there is a lack of accommodation and facilities generally and tourism is currently limited. Mkhomazi KZN Wildlife Office entrance to the Park has reasonable access from the Nottingham Road area but no facilities or campsite and, although it has superb, remote walking country available, has little to offer the confirmed day walker. Similarly Vergelegen, which has its own access distance issue, has no facilities and many of the paths are overgrown. Certainly it is a great start point for longer forays into the High Berg but day visitors rarely go there.

Local Zulu craft worker

The Drakensberg is an area with massive potential for walking and is South Africa’s most popular walking area. Backpacking with appropriate gear including food, a stove, sleeping bag, and a tent or a cave for overhead cover extends horizons considerably. However, of the visitors to the Park, the majority plan on returning to their base accommodation before nightfall. This applies particularly to foreign visitors who are unable to bring equipment on the scale required within the constraints of airline baggage allowances, and who may not wish to locate, hire and then collect equipment after arrival, or do not wish to hire a guide with equipment.

This book is aimed specifically at those who wish to do walks that can be completed in a day. There is something here for families with small children, as well as intermediate walks and some much tougher challenges.

Getting there

Access to South Africa by air is currently almost entirely through Johannesburg. Most European long-haul carriers fly there directly (including British Airways and Virgin Atlantic from London Heathrow) as does South African Airways. There is an Emirates flight from Dubai directly to Durban and Turkish Airlines fly there from Istanbul. The routes have become quite competitive and it is well worth using an agent or the Internet to seek out the best fare, even if it means a change of flight in a European city. From the United States there are non-stop flights to Johannesburg with Delta (Atlanta) and South African Airways (JFK, New York) plus a direct flight with South African (IAD, Washington) with a refuelling stop in Accra.

Visitors from the EU and Switzerland do not require a visa to enter South Africa. Residents of other countries should check at www.home-affairs.gov.za.

There is no public transport to carry you into the Drakensberg so self-drive is the only reasonable possibility. There are many car hire companies located in the airports.

Almost everyone gets to the area from or via Johannesburg or Durban. From other locations the main axis of the N3 toll road still applies unless you design your own cross-country route. Although ‘N’ roads may have central barriers and slip-road exits there are important differences from European motorways. Pedestrians are frequently seen, there is some hitchhiking, livestock may wander onto the road and petrol stations can be relatively long distances apart. There is a series of small towns, some a little way off the N3, which are recognised ‘feeders’ for the Drakensberg and where you can refuel and pick up supplies, especially important if you are self-catering.

A good route-planning road map is important for identifying the shortest or the most interesting way of getting to your destination in the Drakensberg once you leave the N3. Many by-roads are unsurfaced, can be very rough and in wet weather may make for challenging driving conditions. Even surfaced roads may have huge potholes.

Even surfaced roads need vigilance

From Johannesburg

Leaving OR Tambo International Airport you exit on R24 which joins the N12 briefly before you take the slip road L onto the N3. This road and its southern destination of Durban are well signposted. It may be busy and slow at rush-hour times but is navigationally simple. The first key town is Harrismith, about 3hrs steady driving from the airport. From then on the relevant exits and some associated notes are shown under the headings of the individual Park sections. Generally the signposting from the N3 is satisfactory.

From Durban

King Shaka International is the airport for Durban and is sited at La Mercy, some 30km north of the centre of the city. There is a connection from the airport to the N2, the north–south main coastal road. Drive south and after about 30km join the N3 at a large interchange, following signs for Pietermaritzburg which is about 80km distant.

Soon after Pietermaritzburg opportunities arise to leave the N3 axis to make your way into the Drakensberg area of your choice. These are detailed in the information box at the beginning of each geographical section. Wherever you are heading, Durban is closer than Johannesburg, sometimes substantially.

Fuel, cash and permits

Some hotels and some of the camps in the Park have petrol supplies but this can be unreliable. So it is wise to fill up before you leave the N3 or in one of the feeder towns.

Some B&Bs, park entrances and local guides only take cash payments. This means carrying a significant sum with you as driving back to an ATM will be time-consuming and expensive.

You will need R40 per person per day (2016 price) for your mandatory park permit though rates may vary from area to area. They are available from the park entrance gates during normal working hours (usually 8am to 4pm, often closed for lunch).

Accommodation

Many parts of the Drakensberg are comparatively remote. Given that some areas have little choice of accommodation it is very important to secure this in advance to obviate a wasted, long and possibly awkward drive. This is particularly relevant in the case of the KZN-Wildlife rest camps, often fully booked many months in advance.

The South African peak holiday times are Easter, most of December and the first half of January. Bookings can be made by telephone, especially from South Africa, although it is also increasingly possible to book over the internet.

In the sections of the book which cover the individual geographical areas of the Drakensberg some indication is given as to whether accommodation is plentiful or sparse together with some recommendations from the author’s personal experience (although standards may change from year to year).

Some of these accommodation details, including general websites which contain information on hotels, bed-and-breakfast establishments, rest camps and so on, are listed in Appendix C, together with telephone numbers where available. Nevertheless, there is no real substitute for doing your own research because it is more fun and brings to your attention all sorts of other interesting stuff.

A spring day at Cobham – snow can occur at any time of year

The climate – when to visit

The Drakensberg has summers with hot days and refreshingly cool evenings but accompanied by high rainfall, often with thunderstorms which can be frighteningly dramatic. The maximum temperature in the valleys is around 35°C. In summer cloud cover is very common on the summits.

Winters can be very cold, especially at high altitude. At night on the summit plateau the temperature may be as low as -20°C. Although, frost occurs frequently and heavy snow is possible,the overall precipitation in winter accounts for less than ten per cent of the annual total.

It is difficult to recommend a ‘best time’ for visitors who want to walk in the Drakensberg. April and May are usually excellent with reasonable daytime temperatures but cool nights and, importantly, blue skies with low average rainfall, but this is not absolutely reliable. The downside of May and June is that there may be some haze related to the burning programmes (see ‘The Habitats’ above) but this really only interferes with photography. September is often a good month with all the signs of emerging spring, and daytime temperatures rising nicely. The higher rainfall season is just beginning at that stage. From mid-October to March rainfall is quite high, and manifest especially as heavy thunderstorms in the afternoon. So to a certain extent it depends why you are visiting the Drakensberg. For long hikes, the end of April, May and possibly June or September are excellent. In summer they are still possible but a very early start is required. For flowers and birds November and December have much to offer.

Royal Natal National Park – visibility on the plateau can be limited for days at a time

The important underlying message is that temperature, rainfall and wind are, notwithstanding charts showing averages, unpredictable. Sudden changes in the weather are notorious. The bottom line is that whenever you visit you should be prepared for almost any conditions at any time.

Health matters

Malaria

There is no risk of malaria in the Drakensberg.

Gastrointestinal infections

All travellers recognise that there is a risk of gut infection when travelling abroad. When there is any question of contaminated supplies, simple precautions such as avoiding fruit that you can’t peel and drinking bottled water or other drinks will minimise problems.

In the Drakensberg the question of whether or not to drink from mountain streams is an important one. If there is human habitation upstream it should be absolutely ruled out. If there is Baboon habitation upstream the risk is uncertain but probably remote. Some infections can, however, be passed from animals to humans through water supplies so the risk, however small, does exist.

Medical authorities often advise against drinking from streams. However, generations of South African hikers (and the author) have partaken of delicious, cold and sometimes very necessary refreshment from this source without harm. You must decide.

Most walkers drink safely from streams

Dealing with snake bites

Some common-sense practical steps considerably lessen the risk of significant snakebite. Wearing proper walking boots and thick socks in the Berg provides some defence against an inadvertent step onto a basking snake, and gaiters add a little more protection. Don’t put your hands under logs or masonry and never into holes in the ground, especially in old termite mounds. And never, ever, pick up snakes even if you think you recognise their harmlessness, unless you are a real expert.

Most venomous snakes can control whether or not they inject venom in a bite and if so in what volume. Therefore, to be bitten by a venomous snake may not be associated with envenomation and symptoms. The circumstance where no venom is injected is known as a ‘dry bite’. If the snake delivering the bite has been recognised all well and good but do not try and follow it with intent to kill on the basis of information gathering or revenge. This tactic may lead to a doubling of casualty numbers.

Symptoms

Generally the earliest symptoms after snakebite are those of anxiety related to fear of the consequences. These may include dryness of the mouth, sweating and tachycardia (fast heart rate) with nausea. With cytotoxic venom there is immediate and severe burning pain at the site of the bite and then local swelling which may continue for two to three days.

After neurotoxic envenomation there may be local pain but little or no swelling, with drowsiness, vomiting and increased sweating within five to 30 minutes. Later, from 30 minutes to three hours, more obvious nervous system effects emerge which may lead ultimately to difficulty with swallowing or breathing.

First aid management

The victim needs to get to an appropriately-equipped medical unit as soon as possible. This may be difficult. Fortunately, you usually have three to four hours at least to accomplish this and it has been reckoned that even without any first-aid or formal medical treatment at least 98 per cent of snakebite victims survive.

However, all walkers in the Drakensberg should have a sound knowledge of basic First Aid including CPR. Some areas are very remote and accidents happen.

So what steps can you take and should you not take in preparation for evacuation?

Immediate action

Keep calm

Get help whenever possible. There may be a mobile phone signal. It may be necessary to send someone for help.

Things you SHOULD do

Keep the victim still and calm. Reassurance is an important management tool and it is always worth reminding those bitten that most recover completely without any treatment. (They won’t believe you if you are panicking yourself.) Unnecessary movement may hasten the spread of venom.

Expose the wound and wipe away excess venom

Remove tight clothing, jewellery and shoes

Immobilise the affected limb

Be prepared to give CPR if any sign of difficulty in breathing

If the snake has successfully projected venom into the eyes, rinse the eyes out with, ideally, running water. Alternatives are milk, beer, other cold drinks or urine.

Things you should NOT do

Do not cut, squeeze or suck the bite

Do not give an electric shock to the bite – there is no evidence of efficacy

Do not give alcohol

Do not administer antivenom – indeed don’t carry any!

Download onto your cellphone the free app ‘Snakebite First Aid’, devised by the African Snakebite Institute. Then read it.

Dehydration

Even at some of the modest temperatures experienced in the Berg, slogging up hills with a rucksack induces considerable water loss. Most people don’t replenish this sufficiently and feel at least uncomfortable and, at worst, increasingly tired and weak before they realise their plight. Carrying enough water for your needs is tough because of the weight penalty but is absolutely essential. At least two litres a day is a minimum for all but the shortest outings.

Altitude problems

Although the altitudes are never extreme many people will find the going tougher if they are unaccustomed to walking above, say, 2000m. In particular, driving up the Sani Pass to then climb Hodgson’s Peaks will be sufficient to give most people a sharp reminder that they will need to reduce their normal speed of march. Dehydration is more of an issue too if you’re working harder.

Immunisation

Well before departure consult your family doctor, from whom current national advice will be available. It should go without saying that unprotected sex might have extremely serious consequences.

Health insurance

This is absolutely mandatory when you go anywhere outside your own country, unless you have unlimited capital and are unconcerned about parting with a large amount of it. It is worthwhile reading the small print most assiduously. Pay particular attention to anything related to restrictions on the terrain that is covered by the policy and anything involving mountain rescue.

Health care in South Africa

Standards of health care in South Africa can be as high as anywhere in the world and this applies particularly in the larger cities. In very rural communities the facilities and specialist expertise available are less predictable. Generally, the concept of transfering problem cases to a larger and better-equipped unit is well accepted, but distances are long and some minor roads are poorly surfaced, rendering transfer times longer than anticipated if air transport is unavailable.

Safety

Mountain rescue

Entry permits for the Maloti-Drakensberg Park are mandatory. This includes a component to cover you in the event of rescue being required.

Optimum group size

Most authorities recommend three or four as the minimum number, especially for travel up on the escarpment: at least one to stay with a casualty, at least one to run for help if necessary. For the purposes of walks in this book the same number applies, but in practice, up to and including the Contour Path, many pairs of walkers are encountered. In good weather most people find that acceptable. The difficult question is whether one should walk alone? There is no simple answer to this as there are so many variable factors involved, but if a lone walk is your preference and decision, it is absolutely essential that route and estimated return time are recorded at a place where it will checked later.

It is interesting to note that, although it is a bounden duty for all walkers to act responsibly and reduce to a minimum the chance of needing to call out a rescue party, the Drakensberg Park authorities continue to stress that you, the walker, have a ‘Right to Risk’. Many will find this a refreshing attitude.

Security

Sadly, at the time of writing South Africa carries a reputation for increasing lawlessness. Car-jacking is relatively common and mugging, as in the UK, frequently reported in urban areas. However, most tourists never experience any security problems and preventative measures are broadly similar to those that many take in their own country.

Within the Drakensberg Park it is highly unusual for significant incidents to occur which involve tourists. Lone walkers are not uncommon and pairs more common than any other group in our experience. There are prominent warnings about avoiding contact wherever possible with Basutho traders and smugglers (often of marijuana, locally called ‘dagga’) who may also do some stock rustling on the side. If you encounter them on the path move aside. It is reasonable to acknowledge their presence with a polite wave or a ‘hello’ but don’t engage with them and never take photographs or ask to see what’s in their sacks. It is sensible to ask for local advice about this aspect of safety wherever you are.

THINGS TO CONSIDER FOR MAXIMUM SECURITY

Do not leave very valuable or important items in an unattended car even if they are well concealed. Never leave passport, credit cards or money.

If you have the misfortune to have a puncture try keep an eye on your luggage. Offers of assistance are common and usually friendly and supportive but a gratuity is welcomed so have some coins at hand.

It is generally agreed that it is inadvisable to travel by road in the countryside, even on major roads, at night.

In hotels use the room safe if there is one or hotel security if there is not. Don’t leave precious items in plain view. It may offer temptation to low-paid people and is unfair on them if you mislay an item and presume it stolen.

In the street don’t flash wads of banknotes, expensive jewellery or electronics that might attract would-be-muggers.

Completing the mountain register is vital

Useful telephone numbers

Consider putting key telephone numbers (see Appendix C) in the contact list of your mobile telephone (cellphone). Add the number of your accommodation as well and, possibly, your insurer’s number and airline office contact. Always make clear which number is the Emergency Contact number for your next of kin.

Communications

Apart from hotels, generally in South Africa the mobile phone (cellphone) is king and has quite good coverage, although in the mountains this is much less predictable.

Some KZNW camps have a good signal but once out in the Berg the most reliable reception areas are on ridges or summits. In respect of safety you should assume lack of signal. For visitors from abroad, to reduce costs consider taking an old phone with you and purchasing both SIM and airtime on arrival.

In case of serious issues arising on your walk, ensure you have the numbers of your accommodation, the police and the KZN Wildlife emergency service (ask at the local office) nestling in your contact list.

Wifi availability is poor away from hotels and some cafés. In my experience only a few B&Bs and KZN Wildlife lodges offer internet connectivity. Visitors usually have to rely on 3G for Internet access.

Maps

For walking maps of the Drakensberg there is a series at 1:50,000 scale published by KZN Wildlife and last revised in 2003. In this book they are referred to as KZNW maps. The geographical areas covered by the six available maps are as follows (with some overlap):

Hiking Map 1 – Royal Natal National Park

Hiking Map 2 – Cathedral Peak and Monk’s Cowl

Hiking Map 3 – Giant’s Castle and Injisuthi

Hiking Map 4 – Highmoor and Kamberg

Hiking Map 5 – Cobham and Lotheni

Hiking Map 6 – Garden Castle and Bushman’s Nek

THE GIANT’S CUP TRAIL

The Giant’s Cup Trail is a long-distance hiking route which, although in some places a little distant from the high ’Berg, makes a fine walk either in its entirety or in stages. Conventionally hikers take five days to make the 60km journey from the start in the Sani Pass to the finish at Bushman’s Nek and make overnight stops at the strategically sited KZNW huts, Pholela, Mzimkhulwana, Winterhoek and Swiman, finishing at Bushman’s Nek. You may start this hiking tour only at an official starting point and may stay only in overnight facilities provided for this purpose. Tents are not permitted. The cost of the overnight hut stays is subject to change and places must be reserved beforehand. Enquiries and bookings can be made by telephone or letter to: Reservations Officer, KwaZulu-Natal Nature Conservation Service, PO Box 13069, Cascades, 3202, tel (033) 845 1000, email: bookings@kznwildlife.com.

The 1:50,000 scale is acceptable for walking trips in this area. Unfortunately this Drakensberg series has limitations in that some paths and other features are incorrectly plotted, sometimes significantly so in navigational terms. Later editions of the maps may correct inaccuracies. Note that in the current edition all references to caves with Bushman paintings have been excluded to reduce the possibility of vandalism.

The routes in this guide are accompanied by sketch maps. Red dashed lines are used to illustrate routes that have been walked and validated. Red dotted lines are either alternatives that have been explored (indicated on the sketch) or just other paths you may encounter.

Maps are drawn to scale and based on GPS-derived information but they are just sketches and should be used in conjunction with the appropriate map. A map and compass should be regarded as essential equipment.

Using this guide

Route gradings