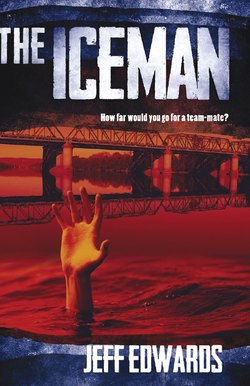

Читать книгу The Iceman - Jeff Edwards - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеI

t lurked below the surface like a malicious spider tending its web.

Ever present since time out of mind, ever alert, it never rested.

The Iceman lay in wait for its next victim and the passing of time meant nothing. If time is what it took, the killer was prepared to wait for decades and it had done so on many occasions.

Sometimes there might be as many as three or four victims in the space of a year, but those were rare. Usually they came after a space of many months or years, long enough for the memory of the previous victim to fade from minds of those who now dared approach the Iceman’s territory.

In recent years, and long after our story begins, the Iceman’s true nature was identified by those who sought to solve such mysteries and who loved to debunk the ancient legends. Even this mattered little to the Iceman. It remained where it had always been and continued to do what it had always done while ignoring the passing of time and the futile attempts of those who had sought to reveal the Iceman’s true nature.

Signs might be posted to warn the public of its presence, but these merely slowed the numbers of victims but never stopped them completely. There were still enough of the drunk, the fool-hardy or the stupid to ensure that the Iceman would continue to hold sway over its territory and to ensure that the legend continued.

Above the Iceman life went on as if nothing of note lurked below. There the summer sun shone and the river flowed gently while waterfowl dived for their dinner amongst the reeds and rushes that lined both banks.

An untrained observer looking across the expanse of water would find it hard to reconcile the warnings with the placid scene before him and this had led many a victim to his doom.

On the bank opposite the village of Henswytch was a short stretch of level ground interspersed with willows which suddenly gave way to a low but very steep cliff where the river had dug its way through a previously flat area to its present lower level. At the top of this cliff and running along its rim, a stand of ancient oaks stood sentinel before surrendering to the expanses of open country beyond. Here the rest of the ancient forest had been cleared centuries before and numerous farms now made full use of the rich alluvial soil.

Downstream from the village on a rise above the river and out of reach of its occasional flood waters stood an ancient fieldstone farmhouse that had been for generations the ancestral home of the Stevens family. In the prosperous years before World War I the family had moved to larger, more palatial premises which were closer to the township and left the cottage vacant. On the death of Samuel Stevens it had been bequeathed, along with the field surrounding it, to the people of the village for its explicit use as a clubhouse for the yet-to-be-formed Henswytch Rowing Club.

Samuel had been an avid sculler from his days at boarding school and later at Eton. His sons had eagerly followed in his footsteps. The less wealthy men of the village of Henswytch had been induced to follow the example of the town’s principal land-owner by the sums of money that could be won by betting on the outcome of the events. Henswytch in its early years had never been large enough to be able to assemble enough able-bodied men in the one place and at the one time to form either a football or cricket team, while a boat crew of strong-backed farm workers could usually be found to man a quad scull, or at the very least, a coxed pair.

The other and far more logical reason for their interest in rowing was that the village was located in an ideal place for this particular sport, on the banks of the Henning River. Winding as it did through the Ladscombe Valley, the Henning River had for some reason known only to nature managed to stop its mean-derings for a short time and forge an arrow straight path from Henswytch to a point just over a mile downstream to where the old fieldstone cottage of Samuel Stevens stood. This straight stretch of navigatable river had gained the village its reputation as a centre for the rowing fraternity and when Samuel and his sons paid for a weir to be built across the river below this point it ensured that the rowing course would always be available, even when the river level dropped.

When plans had been made for the construction of a railway line, Stevens had used all his influence and much of his money to ensure that the line crossed the Henning River at Henswytch and that a station was built in the village. This meant that the rowers and the cheering crowds that followed the sport could be transported easily and quickly to the regattas at Henswytch.

As Henswytch lay upstream, the races began in the village itself. Here, the spire of the local church was used as a reference point for the starting position and the course then ran downstream to end at a point right outside the rowers’ clubhouse. Here, excited onlookers gathered on the banks of the river to cheer the crews to victory while the successful punters collected their winnings.

When the Henswytch Rowing Club was formed with Samuel’s son David elected as its first president, the old farmhouse was transformed from a dark and brooding farmer’s cottage to a more pleasant and airy meeting place. Internal walls were removed to form a large meeting hall with a bar at one end. The kitchen was retained and meals now sold to hungry rowing enthusiasts, but the most significant change was the almost total demolition of the stone wall facing the river. Here, in even the most inclement weather, the club’s patrons could sit in the warmth of the clubhouse with a whiskey in hand and cheer the racers on through the windows that had now replaced the wall.

David Stevens had smiled with delight at the changes and knew that this was exactly what his father had envisioned when he had made his endowment.

The only thing that cast a shadow over his musings was the fact that their wonderful new clubhouse overlooked the very part of the river where the Iceman lurked.