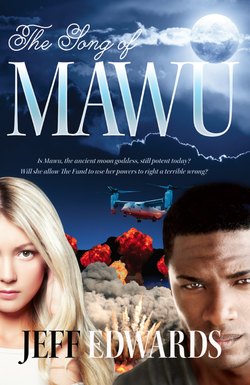

Читать книгу The Song of Mawu - Jeff Edwards - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Rushing down the runway at ever increasing speed the small private jet lifted off from the dusty Namolan airfield and headed into the clear blue sky.

The jet had been chartered by The Fund, a British charity, and it carried three passengers. As it banked to port the sole passenger, on that side of the plane looked down at the sprawling encampment below.

Blue smoke from innumerable cooking fires gave the hastily erected houses a ghostly aspect, and the occupants of those small huts appeared as black specks, moving slowly up and down along the streets which separated the rows of prefabricated dwellings.

A great sadness gripped at Eliza Strang’s chest as she watched the camp and its occupants disappear from view as their plane crossed the coast and headed north.

Seeking moral support, she glanced over the aisle to where her companions sat holding hands. Nori and Ali Akuba were originally from Nigeria and had narrowly managed to escape persecution in their homeland by migrating to England. There they had been able to raise a family and start their own business until Fate in the form of the enigmatic Jade Green, had conspired to raise the couple from obscurity to the position they now held as Directors in The Fund, one of the newest and most heavily financed charities on the world stage.

Nori Akuba, who also had a tear in her eye, smiled sadly and acknowledged Eliza’s look. She too, felt sad at their leaving but knew that it was for the best.

All three of them were tired beyond normal exhaustion and it was a tiredness of the spirit as much as their physical being.

There was always so much to do in the camp, and so very much that they could simply not achieve, no matter how hard they tried.

On more than one night, Nori had dropped exhausted into bed and sobbed uncontrollably. Endless hours of hard work had seemed to prove fruitless, and the refugees she had attempted to care for continued to die. Taking her into his arms, Ali had held her. He had not tried to tell her to stop and allowed her tears to flow while wishing that he could do the same.

Slowly, the three of them had come to the same unpalatable truth. You can’t save everyone, no matter how hard you try. It simply couldn’t be done. Money wasn’t the answer. Some of the poor souls were beyond help when they arrived. There was nothing that the three of them could do even with all the resources they had at their command.

The only answer was tirage. Help for those who could be helped, and as much as it went against everything they held dear, they had to force themselves to ignore those who couldn’t be helped. In that way they had been able to claim some small victories. Lives had been saved and a future, even if it were a precarious one, had been obtained for the lucky few.

***

When the jet reached its cruising height and the seatbelt light had been extinguished, Eliza made her way to the toilet located off the small galley at the rear of the plane.

After relieving herself in the first toilet in months that was not swarming with flies, she washed her face and hands and she took a paper towel to dry herself. As she did so she caught sight of herself in the mirror. It was the first time that she had seen herself in a full sized mirror since arriving in the refugee camp and the sight before her came as a complete shock.

Where had she gone, the young, white faced Goth with her host of body piercings that would have looked back at her a short time ago?

It had begun in Paris of course. The members on the board of The Fund had carefully explained to her that she would never be accepted in Africa in her Gothic dress and makeup so she had reluctantly agreed to the makeover.

Fellow board members, Suzie Ryan and Lana Reynolds had taken Eliza and her friend Justine under their wings and overseen their transformation. Out had gone the Goth, and in her place had arrived a young, middle class professional woman.

Now, standing before the mirror, even that incarnation of Eliza Strang had disappeared to be replaced by her current persona.

Her hair, which had been styled by one of the best hairdressers in Paris, was a complete mess. A perfunctory brush through had done little to give it any shape and it sprung from her head at various angles. Its colour was no longer a dyed black, but more chestnut with lighter streaks where the long days in the sun had bleached the tresses a lighter hue.

Her face, like her hair, had undergone a dramatic alteration. Eating sparingly, working hard and experiencing the soul destroying setbacks of camp life had sucked the youthful fat from her body, and had been replaced by hard, sinewy muscle. The clothes that she had brought with her from England now hung loosely on her spare frame and her once palid skin was now deeply tanned. The eyes in the mirror were now those of a far older, more world-wise person.

With a grimace she recalled how much trouble she had experienced with Customs when she had relinquished her Gothic looks and re-entered Britain bearing a passport photo that looked nothing like her present self and wondered if she would have the same problem yet again. Yet, she realised with a grin, with all the problems she had been forced to overcome in the past months, a doubting Customs official would be of little consequence.

***

Nori watched as Eliza returned to her seat and compared the efficient young woman that she now knew with the wilful young girl that had left England.

The differences in Eliza were obvious and Nori could see that her husband had changed as well. There were now small touches of grey at his temples and his forehead was constantly creased in thought. If he had been reticent about his part in their venture before they had left, he had certainly come into his own when the pressure had been on. Her husband’s personal strength had been the reason that she had been able to carry on despite being forced to watch countless innocent women and children dying around them. It had enabled her to wake up each morning and return to the impossible task of trying to keep a starving, disease ridden population alive for one more day.

She took his large hand in hers, lifted it to her lips and kissed it.

***

Ali looked down at his wife as she took his hand and smiled.

‘It will be wonderful to spend some time with our children,’ he said quietly.

‘Yes. I’ve missed them terribly.’

‘Will we wait for our house to be finished and for the school term to end, or will we collect them from their school’s tomorrow?’

Nori smiled, ‘I’m sure the schools will forgive us if we take them now. We can explain where we’ve come from and I’m positive the children won’t mind if we haven’t moved into our new home yet.’

‘Then we’ll collect them tomorrow.’

Nori kissed her husband’s cheek before resting her head on his shoulder and drifted off to sleep.

***

Eliza watched her friends and was eternally grateful for the assistance that they had been.

When the images of the bloodied refugees flooding across the border from their own war-torn country of Sonateria, and into the relative safety of Namola had been shown on televisions across the globe, the world had seen for the first time how truly savage the intertribal war had become. Thousands had not survived the journey. They had been cut down by machete swinging rivals or blasted to death by Kalashnikov assault rifles. Their bodies lay unburied along the roads that should have led them to safety. Buzzards gorged themselves and were eventually too full to fly away.

Those that did survive the journey had arrived bloodied and wounded in Namola with little or nothing in the way of possessions. Food and water were scarce and the situation became even worse each day as more and more of their fellow countrymen arrived seeking refuge from the slaughter.

As they crossed the border the refugees had been greeted by armed troops from the Grand Army of Namola who refused them free access to the countryside and nourishment. Instead, President for Life, Joseph Lattua had decreed that the unfortunate people be relocated to a dry, rock strewn valley named Ashloko which was completely denuded of flora or fauna. The President had no desire to have unfed refugees wandering the countryside, denuding his lush pastures and stopping his farmers from growing their crops, thereby denying him of much needed tax revenue.

Eliza had spoken to the local Namolan people and learned of the legend of the moon goddess Mawu, particularly the part Loko had played in that drama. Now, having lived in Ashloko, she could well imagine that this was where the sun god Lisa had taken his revenge on the hapless Loko for the murder of Rang the hunter.

The valley of Ashloko was five kilometres wide at its mouth and tapered back in a rough triangle as it rose to meet the mountains that surrounded it. ‘Moonscape’ was the word that sprung to Eliza’s mind when she had first seen photos of it and on arrival the word seemed totally appropriate. With its desert dry atmosphere and rock-strewn floor, the only sign of life was a small trickle of water that was provided by a natural spring near the valley’s mouth and the refugees formed their makeshift camp at this one habitable oasis.

However, the soaring numbers in the camp quickly polluted the meagre stream, and the starving people had denuded the surrounding country of whatever greenery had managed to grow in that desolate place. The stream had become an open sewer and disease quickly spread throughout the camp.

Eliza had witnesed this unfolding on her television screen in England and knew immediately that this would be where she was needed and where she wanted to work.

The rest of the world was not blind to the refugees’ needs either and international aid organisations had immediately swung into action to help. Water and food was the first order of business, while medicine was shipped in to help the wounded, the starving and the diseased.

***

As Eliza began her work in London she learned that there was much help already underway but was also aware that the amount of assistance that could be provided to any one disaster was finite. If another catastrauphic event were to occur, resources would have to be cut back to Namola in order to help with the new problem.

This was why Eliza had decided to undertake this project. The Fund, as a charitable organisation, had decided that it would not interfere with those aid efforts that provided immediate relief but would set out to provide a more permanent solution to the existing problems. They intended to do this by setting in place permanent works projects that would enable the refugees to survive long after the other charities had moved on.

She had begun by hiring an engineering company in South Africa and issuing orders for them to travel to Namola to locate a permanent potable water supply in the vicinity of the refugee camp.

It had taken them several months and Eliza was forced to spend her time in England trying to fill in the days by planning and purchasing the equipment which would be necessary for the second phase of the project.

Finally, the wonderful news had come through. By drilling at the far end of the valley the engineers had struck an artesian basin at a depth of approximately two hundred metres. The water itself was slightly alkaline but still potable and they had immediately capped the well, taking great care to disguise its presence as she had instructed.

Ali Akuba had done most of the face to face negotiations with the very difficult and extremely corrupt, Namolan public service. The Fund had, for a relatively small amount of money, had been able to lease the land around the new well on a long-term basis.

The Namolans had considered Ali a rather stupid person for wanting to rent such an uninspiring piece of real estate and Ali had ‘forgotten’ to tell the Namolans that there was now a source of water to be found in the arid valley. He knew that they would never bother to visit the site themselves because it was too close to the refugee camp and the crowds of sick people forced to live there.

With the land and the precious water supply in their possession, Eliza quickly moved to the next stage of her plan.

***

Using The Fund’s very tenuous relationship with the British Government, the Directors lodged a list of very unusual requests with Prime Minister David Foster.

These ‘requests’ resulted in Diplomatic talks taking place between the British PM and President Joseph Lattua of Namola, whereby the Namolan President eventually agreed to allow their British friends to conduct a short military exercise in the hard desert of the Ashloko Valley.

The exercise was designed for British sappers to test the delivery, use, and retrieval of their heavy earthmoving equipment under wartime conditions in co-ordination with the forces of the Grand Army of Namola.

***

So it was on a clear evening a week later, that the Grand Army of Namola moved in battle formation to set up a secured perimeter and protect a specified area from a mythical invading force.

Once the area was ‘secured’, a message was radioed to nearby British Forces and a short time later the Namolian troops heard the distant roar of several approaching aircraft.

Three military transports, their loading ramps lowered, flew in low and disgorged their cargos, which floated down beneath large parachutes to a prearranged drop zone. These were followed by a second wave of aircraft who came in higher, from which a company of sappers parachuted to join their equipment that had already reached the drop zone below them.

Once the sappers had landed and stowed their parachutes, they formed up and were issued further instructions from their sergeants. Quickly and efficiently the men moved off to their allotted tasks.

Once the sappers had landed and stowed their chutes, they quickly moved into position to undertake their assigned tasks. The large steel containers were flung open and the machinery inside driven out. Meanwhile, other sappers used GPS positioning equipment to mark out the position and dimensions of the runway that they were about to construct.

As the sun rose over the lip of the valley, the British engineers were already hard at work clearing a long stretch of valley floor. They were aided by the willing hands of the Grand Army of Namola, who were all excited about showing off their prowess to their more illustrious friends.

After a day of hard work, a sufficient distance had been cleared for the first plane to land, which it did at first light the following day.

From then on a steady stream of aircraft arrived, deposited their loads, and took off, leaving additional troops and heavier equipment which was now used to extend the length of the runway and to erect prefabricated sheds and housing.

A week later a small township of prefabricated buildings had been created, complete with latrines, shower blocks and mess halls.

The members of the Namolan army watched the birth of the town with expressions of wry amusement. Why do all this work in a place like Ashloko? What was the point of it all?

The British officers patiently explained to their Namolan companions that it was a practice exercise in case they needed to do the same in the future and under actual battle conditions.

The Namolans shrugged their shoulders, accepted the fine food served in the mess hall and laughed at the silly British soldiers when their backs were turned.

Finally, the construction was declared to be complete and the British began to pack their equipment into the planes that were once again landing at regular intervals. Less than two days later, the last of the British soldiers were gone and the Namolans returned to their barracks outside Lobacra, much amused by the antics of the silly foreigners.

***

In the baking heat of Ashloko stood a now silent township left behind by the departing troops. They had shown no interest in dismantling and removing the buildings and not far from the village stood the dirt runway stretching into the distance.

From the rim of the valley an observer would have noted a strange new feature on the landscape. A defensive ditch had been dug from the top of the valley to a place close by the refugee camp. Along the length of this ditch were wide and deep holes, giving the whole work the look of a giant’s necklace.

What the departing troops had not been told was that the facilities left behind had been paid for by The Fund and stood on the land which they had leased from the Namolan government.

All was now in place for stage three of Eliza’s plan.