Читать книгу The News - Jeffrey Brown - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

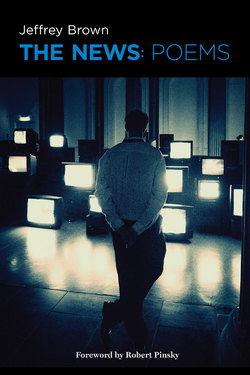

ОглавлениеForeword

Jeffrey Brown in this book apprehends some specific realities: the news as a medium and the news that is the medium’s object. Brown’s poetry examines that material in a new way, giving it a fresh, urgent form. I mean form as the term applies to sports or dance: an effective, useful organizing of energy. The News is more than a venture into art by someone prominent in another field. In these poems, an unconventional subject for poetry is dealt with from within, by a real poet.

“To see beyond the camera,” says Brown about his purpose. The phrase works in two directions. Looking outward, these poems strive to see beyond the camera’s instrumental vision of what is before it, the stuff of the daily news: disasters and elections, celebrations and wars, famous artists and notorious criminals. Looking inward, Brown offers a vision from the other side of the camera: the feelings, understandings, and bewilderments of the makers who work behind the instrument, directing and controlling its gaze.

Jeffrey Brown respects his profession. His belief in the value of news reporting, along with his ways of questioning the processes, gives a spine of purpose to The News. Jaded skepticism would be trivial, and preening would be even worse. Pride in the work, along with candid fatigue and misgivings, animates the poet’s quest to get what the news medium and its devices can see externally and what it can know internally.

Ultimately, this subject matter is as mysterious as culture itself. More immediately, it has immeasurable importance in the political realm, the world of power. Brown treats that world, its eminences and accomplishments, its thugs and abominations, with the passionate, lyrical understatement of a onetime classics major.

For example, in the first, dedicatory poem, within the span of eleven lines there is a credible, human-scale exchange of words between two people—traveler and hotel porter—along with a sense of the planet itself, in its astronomical scale. That concentrated vision of the local and the global is achieved partly by how the poem’s final words, “a wider world. // And you in it, you carried in it,” echo an earlier stanza:

Uniformed, night-shifted

a man crossing borders

in the satellite’s beam—

The satellite’s beam, transmitting news of the world, possibly illuminating as well, prepares the scale of the “wider world” one can enter, and be helplessly carried by: the human, social world and the planet, both irresistibly, necessarily in motion, reflected by rhythms of stanza and line.

Another example of art, from “Haiti”:

La Saline—the giant slum

on a sun-soaked shit-soaked morning

as the children filled their buckets

from a makeshift well. The pigs

scavenged while a rat watched

all. Why bother to hide?

The approximately three-beat lines begin with a rational juncture after “giant slum” and the same, a little more rapid, after “shitsoaked morning,” then more rapid again as the sentence strides across the line break, noun to verb, on “The pigs / scavenged,” and ending at the most violent enjambment: “while a rat watched / all.” The tension between line and sentence, reflecting the tension between poetry and fact, increases steadily. In the space between the observer and these plague-menaced children, the emotion builds.

More than once, the poems deal with extreme situations by letting someone in the place and of the place have the last word. “Haiti” ends not with the poet’s voice but with the words of a man whose son was among the many who died: “I am a bird left without / a branch to land on.” Another poem, “Taha Muhammad Ali,” cites the Arab poet, who has said, “No ‘Palestine,’ no ‘Israel’ in my poetry /… but ‘suffering, longing, pain, fear.’” Taha Muhammad Ali, in the poem’s last words, presents a question: “Do you know the meaning of a meal?” This artful resolution by quoting, or attribution, is partly the resource of an expert interviewer. It is also a way of resisting resolution, a gesture away from various frames—the newsman’s viewfinder or screen, the poet’s page or stanza—toward the actual, bewildered, or bewildering texture of one person’s experience.

That focus on particular lives also governs the sequence “Honor Roll,” which attends to particular soldiers and marines. Their deaths are against the backgrounds of Afghanistan and Iraq, along with the reported and imagined texture of each individual. The poems of the sequence are as direct and plain as snapshots.

The News also includes poems based on the poet’s own life. Others are based on professional conversations with artists, including Mark Morris and Philip Roth. At the center of all, implicitly or explicitly, is the main concern: trying to see past the surface, past what the camera can show or mean. The recurring action is one of deferral rather than arrival—an acknowledgment that the very act of observing, every necessary effort to report, creates its own distortions. The last poem in the book, again set in Haiti, again ends with the words of someone other than the poet:

In Kacite they passed out purification tablets

displayed with pride their new latrine.

A woman sweeping her dusty steps—

asked to act naturally for the camera

to act as though we’re not here—

more honest and aware than us, replied:

How can I pretend that you are not here?

Was that not you who spoke just now?

By honoring the human voice, Jeffrey Brown has brought a remarkable, fresh kind of attention to these questions of identity and presence, delusion and awareness—in the specific realm of television news and in life itself.

Robert Pinsky