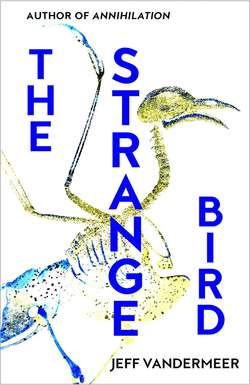

Читать книгу The Strange Bird - Jeff VanderMeer - Страница 5

ОглавлениеFor Ann

The Escape

The Strange Bird’s first thought was of a sky over an ocean she had never seen, in a place far from the fire-washed laboratory from which she emerged, cage smashed open but her wings, miraculous, unbroken. For a long time the Strange Bird did not know what sky really was as she flew down underground corridors in the dark, evading figures that shot at one another, did not even know that she sought a way out. There was just a door in a ceiling that opened and a scrabbling and scrambling with something ratlike after her, and in the end, she escaped, rose from the smoking remnants below. And even then she did not know that the sky was blue or what the sun was, because she had flown out into the cool night air and all her wonder resided in the points of light that blazed through the darkness above. But then the joy of flying overtook her and she went higher and higher and higher, and she did not care who saw or what awaited her in the bliss of the free fall and the glide and the limitless expanse.

Oh, for if this was life, then she had not yet been alive!

* * *

The sunrise that blazed out from the horizon across the desert, against a wall of searing blue, blinded her and in her surprise made the Strange Bird drop from her perch on an old dead tree to the sands below.

For a time, the Strange Bird kept low to the ground, wings spread out, frightened of the sun. She could feel the heat of the sand, the itch of it, and sensed the lizards and snakes and worms and mice that lived down below. She made her way in fits and starts across the desert floor that had once been the bed of a vast sea, uncertain if she should rise for fear of being turned into an ember.

Was it near or far? Was it a search light from the laboratory, trying to find her? And still the sun rose and still she was wary and the air rippled and scorpions rustled out and a lunging thing upon a distant dune caught a little creature that hopped not far enough away and the air smelled like cinders and salt.

Am I in a dream? What would happen if I leapt up into the sky now? Should I?

Even as under the burning of the sun her wings seemed to grow stronger, not weaker, and her trailing passage grew bold, less like a broken wing and more like a willful choice. The pattern of her wing against the sand like a message she was writing to herself. So she would remember. But remember what?

The sound of the patter of paws kicking up sand threw the Strange Bird into a panic and she forgot her fear of the burning orb and flew off into the air, almost straight up, up, and up, and no injury came to her and the blue enveloped her and held her close. Circling back over her passage, against the wind, taxing the strength of her wings, she spotted the two foxes that had been sniffing her trail.

They looked up at her and yipped and wagged their tails. But the Strange Bird wasn’t fooled. She dive-bombed them once, twice, for the fun of it, and watched them yelp and look up at her with an injured look in their eyes, even though behind it lay a cold gleam and ravenous smiles.

Then she wheeled high again and, taking care not to look directly into the sun, headed southeast. To the west lay the laboratory where they had done such beautiful, such terrible things.

Where was she headed, then?

Always to the east, always veering south, for there was a compass in her head, an insistent compass, pushing her forward.

What did she hope for?

To find a purpose, and for kindness, which had not yet been shown to her.

Where did she wish to come to rest?

A place she could call home, a place that was safe. A place where there might be others of her kind.

The Dark Wings

The next day a vision of a city quavered and quivered on the horizon alongside the sun. The heat was so intense that the city would not stop moving through waves of light. It resembled hundreds of laboratories stacked atop and alongside each other, about to fall over and break open.

With a shudder, the Strange Bird veered to the southwest, then east again, and in a little while the mighty city melted into bands and circles of darkness against the sand, and then it vanished. Had the sun destroyed it? Had it been a kind of ghost? The word ghost felt gritty in her head, something unfamiliar, but she knew it meant an end to things.

Was the laboratory a ghost now? Not to her.

On the seventh day after the intruders had dug their way up into the laboratory … on that day, the scientists, cut off from supplies, and under siege in the room that held the artificial island meant only for their creations, had begun to slaughter the animals they had created, for food.

The Strange Bird had perched for safety on a hook near the ceiling and watched, knowing she might be next. The badger that stared up, wishing for wings. The goat. The monkey. She stared back at them and did not look away, because to look away was to be a coward and she was not cowardly. Because she must offer them some comfort, no matter how useless.

Everything added to her and everything taken away had led to that moment and from her perch she had radiated love for every animal she could not help, with nothing left over for any human being.

Not even in the parts of her that were human.

* * *

She encountered her first birds in the wild soon after she left the ghost city behind, before turning southeast again. Three large and dark that rode the slipstream far above her and, closer, a flock of tiny birds. She sang out her song to them, meant as friendly greeting, that recognized them as kin, that said although she did not know them, she loved them. But the little birds, with their dart-dots for eyes and the way they swarmed like a single living creature, rising up and falling down wavelike, or like a phantom shadow tumbling through the air, did not recognize her as kin. There was too much else inside her.

They treated the Strange Bird as foe, with a great raspy chirping, the beat of wings mighty as one, and raked at her with their beaks. She dropped and rolled, bewildered, to get below them, but they followed, pecking and making of their dislike a vast orchestral sound, and she wore a coat of them, felt their oily mottled feathers scraping against hers.

It was an unbearable sensation, and with a shriek the Strange Bird halted her dive and instead rose fast, tunneling up through a well of cold air, against the weight of her kin, until the little birds peeled off, could not follow that high and they became a cloud below, furious and gnatlike. While the cold wind brought her a metallic smell and the world opened up, so the Strange Bird could see on the curving edges that the desert did end, and on one corner at least turned green and wooded. A faint but sharp scent of sea salt tantalized, faded into nothing, but spoke to the compass within her, which came alive once again.

But now the three dark-winged monsters that had been above her drifted to either side, the feathers at the ends of wide wings like long fingers and their heads gray and bereft of feathers and their eyes tinged red.

They rode the wind in silence for several minutes, and the Strange Bird was content to recover in the dark wings’ company. But a prickling of her senses soon became an alert that the dark wings were probing the edges of her mind, the defenses the scientists had placed there. Walls the Strange Bird hadn’t known existed slid into place and, following certain protocols, a conduit opened while all else became a shield wall, sacrosanct.

Origin?

Purpose?

Destination?

Words that appeared in her head, placed there by the dark wings. She had no answer, but in approaching her, they had opened themselves up and because they were older, they had no sense yet of the danger, of how their own security had been breached by the complex mechanisms living inside the Strange Bird. Much of what was new in them, of their own making, had arisen solely to talk to each other with more autonomy, to become more like birds.

For the Strange Bird realized that, just like her, they were not strictly avian, and that unlike her, parts of them were not made of flesh at all. With a shock, she came to understand that, like living satellites, they had been circling the world for a vast amount of time, so many years she could barely hold them in her head. She saw that they were tasked with watching from above and transmitting information to a country that no longer existed, the receiving station destroyed long ago, for a war that had been over for even longer.

In their defenselessness, performing their old tasks, keeping data until full to bursting, erasing some of it, to begin again, the Strange Bird gleaned a view of the world that had been, saw cities cave in on themselves or explode outward like passionflower blooms opening, a tumbling and an expansion that was, at its heart, the same thing. Until there was just what observed from above, in the light and the dark, sentinel-silent and impartial, not inclined to judgment … for what would the judgment be? And how would a sentence be carried out now that all those responsible were dead and buried? But in these images, the Strange Bird knew that, perversely, the laboratory had functioned as sanctuary … just not for the animals kept there.

The dark wings needed no food. They needed no water. Ceaselessly they flew and ceaselessly they scanned the land beneath them, and never had their talons felt the firmness of a perch or their beaks food. The thought brought an almost human nausea to the Strange Bird.

Shall I set you free? she queried. And in a way, she meant to set the world within them free, too.

For she could see that this was possible, that with the right command, the dark wings would drop out of their orbits and think for themselves, in their way, and rejoin the landscape beneath them. What they would do then, she didn’t know, but surely this would be a comfort to them?

But the query alarmed the dark wings, tripped some internal security, lurching back online. All three gave out a mighty cry, and right there, beside her, they burst into specks of blackness that she could see were miniature versions of their larger selves and the specks dispersed into the thin air. The dark wings vanished as if never there and the Strange Bird’s heartbeat quickened and she flew higher still as if she could escape what she had seen.

Whether in a day or a week, the specks would find each other and bind together again, slipping into the old, familiar pattern, and once more three dark wings would glide across the invisible skin of the world on their preordained routes, performing functions for masters long dead. They might fly on for another century or two, dead-alive, until whatever powered them grew old or distant or the part of them that was flesh wore out.

Yet even as specks roiled by the buffeting wind, the dark wings communicated with one another. The Strange Bird could hear them, mote speaking to mote, sharing intel about her. Telling what must be lies.

Analysis

>>Composition: Avian, overlaid with Homo sapiens, other terrestrial life-forms. Unstable mélange.

>>Mission critical uncertain; synapse control override inconsistent with blueprint of original design. Interference 100 percent certain.

>>Conclusion: Sleeper cells exist. Unknown origin and intent.

>>Action: Avoid a void a void a void!

At dusk, she found a perch atop the rusted hull of a ship that had foundered there in the desert half a hundred years before. She was tired. A sadness had come over her as she had let herself drift across the skin of the sky, watched the desert transform into mountains of rusted electronics, of ancient caravans calcified and fossilized into the dunes.

With the sadness had come the knowledge that the Strange Bird could be mighty—and that she was almost as large as the dark wings. That her feet ended in talons meant to rend, to slice, to tear. That her beak was sharp and curved. That she did not need food like other birds, or did not need it often, could go without. In that, she was more like the dark wings.

As the hidden nocturnal life crept out at the margins and the wind slowed and deepened, the scent of animal musk welled up strong, and with it a metallic aftertaste, by-product of centuries of pollution. Constantly, the Strange Bird’s system purified itself of ghosts, of particles that could kill, all much smaller than a speck of dark wing.

The Strange Bird could see as she alighted there, in her newfound strength, the history of the place in her mind, it rising up as naturally as breathing. Below the ship were buried many others, in the sea of sand that had once been filled with salt water. Even that place, the depth of it, the detail, was almost too much to take in, the world overwhelming.

New things were rising in her, capabilities she didn’t know she had. They flickered on and then sometimes flickered off, as if the laboratory had not quite been finished with her. If she tried, the Strange Bird could reach out across the rim of the world, could feel life pulsing in all directions, even if hidden, even if sometimes in distress or marginal.

She tried to sleep, in the half-awake way that the Strange Bird slept. For always there was an eye inside of her that was awake.

The First Dream

In the dream, the Strange Bird sees a woman with black hair and brown skin peeling a piece of fruit, an apple, from the garden room, and cutting the pieces into pieces and putting them in a bowl. This woman she knows from the laboratory; her name is Sanji. The woman hands the bowl to another woman very much like Sanji but taller and with a rounder face, sitting on the couch next to her. She knows somehow that Sanji’s friend used to work at the lab, but left long before the Strange Bird’s own escape.

In front of them floats a moving image of other human beings talking and walking around. The women watch, joking and laughing. The Strange Bird can see the lab spreading out beyond them, still clean and new and fresh. The lights still work. There is still plentiful food.

Sanji feeds a piece of apple to her companion and says, “I save you from the bad apples. That’s my job. All these years, I’m the only reason you have not died from eating bad fruit. I am all that lies between you and that fate.”

The other woman laughs and squeezes her hand and a second name drops into the Strange Bird’s head, but when she wakes she cannot remember the name.

Only a sense of peace. Only the crisp taste of the apple.

The Storm

Headed ever southeast across the vast desert, the Strange Bird thought the world below looked so very old and so very worn, and only when she climbed to the right altitude could she pretend that it was beautiful.

The Strange Bird tried not to think of her dreams as she flew, for she could make no sense of them, hardly knew what a dream was, for it did not fit her internal lexicon and she had trouble holding in her head the idea of real and not-real.

Any more than did the prowling holograms that swirled up across the dead desert surface from time to time, performing subroutines from times so remote that nothing about them could be said to contain sense. Human figures welled up to walk, yet were composed of nothing but light. Sometimes they wore special contamination suits or astronaut suits. They trudged or they ran across the sands as if real, and then dissipated, and then came back into existence in the position where they had started, to again trudge or run, over and over.

Yet in watching this, the Strange Bird was reminded of the dream, and also of how detritus fell from her to the desert floor. Tiny bits of herself she did not need, and that she did not understand, for the way in which this material left her was too regular to be an accident, and she knew the compass inside her guided its distribution. Each time she regenerated the microscopic part that was lost so she could lose it once more.

In the laboratory, the scientists had taken samples from her weekly. She had lost something of herself every day. It was worse when they added something on, and then the Strange Bird had felt awkward, as if adjusting to an extra weight, and lurched off-balance on her perch, flapped her wings for hours until she felt settled again.

* * *

On the fifth day, just as the Strange Bird had become comfortable with this process—and the sun, the holograms, the cities, the higher elevations where the wind was so cold—a cloud blotted out the edge of the world, coming fast at her. She had not encountered a storm yet, but knew of storms, something inside of her programmed for evasion. But the cloud came at her too swift, too all-encompassing, and only at the last second did she see why: for it wasn’t a cloud at all but a swarm of emerald beetles, and the chittering sound they made as they flew scared her.

She tried to dive for ground cover but misjudged the distance, and the swarm overtook her like a wall, and she slammed into it, lost control of her wings, fell through a thick squall of beetles, progress slowed by their carapaces, righted herself in time to—head down like a battering ram and eyes shut—push through them even as they tore at her feathers and ripped along her belly.

Breaking free of them on the other side meant a lightness that surprised, and she rose more quickly than expected, caught in a tidal pool of air created by their passage. Thought herself free—only to spy just ahead the reason for the beetles’ panic: a real storm, spanning the horizon, and closing fast.

Emergency systems not triggered by the beetles switched on. A transparent sheath slid over her eyes and echolocation switched off so that she might rely on tracers and infrared in the midst of maelstrom.

Then the storm hit and she had nowhere to hide, no plan, no defenses, just the compass pulsing inside of her, and a body pummeled by winds gusting in all directions, trying only not to crash or be ripped to pieces.

The Strange Bird’s strength failed her, and she tumbled, rose and fell only because the wind willed it. Perhaps she called out before something dark with weight spun toward her out of the maelstrom. Perhaps she made a sound that was a person’s name as it struck her broadside, smashed her into a well of turbulence, knocked the consciousness from her. The Strange Bird could not remember later.

But whom could she have called for help? There was no one to help her, was there?

The Prison

When the Strange Bird regained consciousness, head ringing, she found herself in a converted prison cell in a building buried in the sand. Only the narrowest foot-long slit of window at the top near the ceiling revealed the presence of the sun. All was dark and all was hard—the bench set into the wall like a long, wide treasure chest was hard. The walls were hard. The black bars, reinforced with wire and planks of wood, so she could not slip out, were hard. No soft surface for relief. No hint of green or of any life to reassure her.

The smell that came to the Strange Bird was of death and decay and untold years of suffering, and the dim-lit view that spread out before her beyond the bars was of a long, low room filled with odd furniture. At the far end an arched doorway led into still more darkness.

The Strange Bird panicked, felt a formless dread. She was back in the laboratory. She could not find her way out. She would never truly see the sky again. Thrashed her wings and screeched and fell off the bench and onto the bare dirt floor and lay there beak open, wings spread out, trying to appear large and fearsome.

Then a light turned on and the gloom lifted and the Strange Bird saw her captor. The one she would come to think of as the Old Man.

He sat atop an overturned bucket next to a rotting desk and watched her, the rest of the long room still murky behind him.

“Beautiful,” the Old Man said. “It is nice to have something beautiful here, in this place.”

The Strange Bird remained silent, for she did not want her captor to know that she understood, nor that she could, when she wished, form human words, even if she did not understand all of those words. Instead, she squawked like a bird and flapped her wings like a bird, while the Old Man admired her. In all ways, she decided to be a bird in front of him. But always, too, she watched him.

The Old Man had become folded in on himself over time. He had brown skin but pink-white splotches on his arms and face, as if something had burned him long ago, tried to strip him away from himself. He had but one eye and this was why when he stared it was with such purpose and intensity. His beard had turned white and so he looked always as if drowning, a froth of sea foam roiling across his chin, and with flecks of white across his burned nose and gaunt cheekbones. He wore thin robes or rags—who could tell which—and a belt to cinch from which hung tools and a long, flat rusted knife.

“I rescued you from the sands. You were buried there—just your head above. The storm had smashed you out of the sky. You are lucky I found you. The foxes and the weasels would have gotten to you. You would be in something’s belly by now. A special meal.”

The Old Man did not resemble a lab scientist to the Strange Bird and did not talk like a scientist, and his home was no laboratory the more she saw of it. She settled down, relaxed enough to search for injury, discovered soreness and strain but no broken bones. Feathers that had been lost but would grow back. She preened, checked for parasites, split two against the edge of her beak, while the man talked.

“My name is Abidugun. I was a carpenter like my father before me and his father. But now I have been many things. Now I am also a writer.” He gestured to a typewriter, ancient, atop the rickety desk. To the Strange Bird it resembled a metal tortoise with its insides on the outside. “Now I am trying to get it all down. Everything must be put down on the paper. Everything. No exceptions.”

The Old Man stared at the Strange Bird as if expecting a response but she had no response.

“I sleep in the cell when I don’t have guests,” the Old Man said. “The prison is all around us and below us—many levels. I was once a prisoner here, long ago, so I know. But that is ancient history. You don’t want to know about that. No one does.”

Although the prison was vast and the wind echoed through its many chambers during sandstorms, the Strange Bird would learn that all the Old Man’s possessions existed in this long room, for it was where he chose to live and the rest was nothing but hauntings to him.

“I am the only one here,” the Old Man said, “and I like it that way. But sometimes having guests is a good idea. You are my guest. Someday I will show you around the grounds here, if you are good. There are rules to being good that I will share.”

Yet he never shared the rules, and the Strange Bird had already seen the three crosses that stood in the sand outside, which she thought were perches for other birds now long dead. She had seen the tiny garden and well next to the crosses, for she turned echolocation back on and cast out her senses like a dark net across a glittering sea to capture whatever lay outside her cell. The well and garden were both a risk, even disguised as abandoned, derelict, overgrown.

“I am Abidugun,” he said again. “You I will call Isadora, for you are the most dazzling bird I have ever seen and you need a dazzling name.”

* * *

So, for a time, the Strange Bird became Isadora and responded to the name as best she could—when the Old Man fed her scraps, when he decided to read her stories from books, tales incomprehensible to her. She decided that even as she plotted to escape, she would pretend to be a good pet.

But in the lab, the scientists had kept her in a special sort of light that mimicked sunlight and fed her in its way, and now that she had only the barest hint of any light, she felt the lack.

“You should eat more,” the Old Man said, but the kind of food he brought often disgusted her.

“Life is difficult,” the Old Man said. “Everyone says it is. But death is worse.”

And he would laugh, for this was a common refrain, and the Strange Bird believed someone had said it to him and now he was under the spell of those words. Death is worse. Except she did not know anything of death but what she had seen in the laboratory. So she did not know if death was worse. She wished only that she might be that remote from the Earth and the humans who lived upon it. To glide above, to go where she wished without fear because she was too high up. To reduce humans again to the size she preferred: distant ghosts trudging and winking out to reappear again, looped and unimportant.

* * *

Beyond the dune that hid the Old Man lay a ruined city, vast and confusing and dangerous. Within that city moved the ghostly outlines of monstrous figures the Strange Bird could not interpret from afar, some that lived below the surface and some that strode across the broken places and still others that flew above.

Closer by, etched in the crosshairs of her extra perception … a fox, atop the dune, curious and compact and almost like a sentry watching the Old Man’s position. Soon, others joined the fox and she glimpsed the edges of their intent and, intrigued, she would follow them using echolocation whenever she sensed them near, when there was nothing else to do, and for the first time she experienced the sensation of boredom, a word that had meant nothing in the laboratory for there had been nothing to test boredom against. But now she had the blue limitless sky to test it against, and she was already restless.

Her senses also quested down the many tunnels and levels of the prison when the Old Man went hunting, so she might test the bars, the planks of the wood, the wire in his absence. The Old Man often disappeared into the maze down below, with his machete, and hunted long, black weasel-like creatures that lived there. She listened to the distant squeals as he found them and murdered them, and she saw in her mind the bubbles and burrows that were their lives become smaller and smaller until they were not there at all.

How in their evasion and their chittering one to another did the Old Man not realize their intelligence? On the mornings when the Strange Bird woke to find the thin, limp bodies of the black weasels lying half-in, half-out of a massive pot on a table halfway across the room, she felt a sense of loss the Old Man could not share.

The Strange Bird knew, too, that the Old Man might find her beautiful, but should he ever be starving, he would murder her and pluck her dazzling feathers and cook her and eat her, like he would any animal.

She would lie half-in, half-out of the pot, limp and thoughtless, and she would no longer be Isadora but just a strange dead bird.

The Foxes at Night

The foxes came out at dusk and peered in through the slit of the Strange Bird’s cell at an angle where the Old Man could not see them. Their eyes glittered and they meant mischief, but not to her. They sang to the Strange Bird a song of the night, in subsonic growls and yips and barks. They were not afraid of the prison or of the Old Man, for they were not like most foxes, but more like the other animals she had known in the laboratory—alert in a specific way.

So she sang back silently to them, as a comfort, there in the cell, and when the moonlight lay thick and bright against the gritty cheek of the sand dune, the foxes would gambol and prance for the sheer delight of it and beckon her to join them, would let her into their minds that she might know what it was to gambol and to prance on those four legs, then these four legs, to see the world from a fox’s level. It was almost like flying. Almost.

The Strange Bird knew that in those moments, the foxes could see into her mind, too. That the pulsing compass allowed this, attracted them. Yet as time passed, this fact did not concern her, for the freedom was too exhilarating and her prison too dank and terrible. In time, she wanted them to know her mind, for fear she might never be free, that they might take with them across the sands some small part of her.

Soon, she understood the foxes better than the human beings of the laboratory, or her captor the Old Man, and could call to them from across the sands and they would gather at the top of the dune and talk to her. Querulous, they would ask her questions about where she had come from and what it felt like to drift so far above the Earth. Is that place better, where you came from? Would we like it? Worse than your prison? How did you escape?

At night, too, parts of her still drifted off as they had before, through the slit of window in her cell, microscopic tufts that would leave her to become something else somewhere else. She could not know what it meant, what agreement her body had reached with the biologists in the lab that she had never said yes to.

But the foxes celebrated this leaving, for they would jump up in ecstasy at those moments, and snap in play with faux ferociousness at the microscopic things that left her, as if to herd them on their way, up into the sky, to drift and drift, and to never rest.

The Old Man’s Story

The Old Man never opened the cell door but only slid the horrible food in through an opening that he closed with a nailed plank of wood. He seemed to know that the Strange Bird might be able to escape through such a space and into the room without hurting herself.

As he shoved the food in, the Old Man always said, “You’re good, Isadora. You’re good, I can tell. You are beautiful and good.”

But what was good and what was beautiful and why were these things important to the Old Man?

Nothing in the laboratory had seemed good to her, and beautiful was form without function. Anything that might be beautiful about her had a purpose. Anything that was good about her had a purpose, too. And still the compass pulsed within her and at times drove her frantic with the need to escape and thoughts of the dark wings, how they had disbanded and pulled apart and yet come back together.

The foxes had put the idea in her head—that she might escape by becoming a ghost. If she became a ghost, the Old Man could not see her and would think she had escaped and open the cell door so she could truly escape. The Strange Bird knew that the idea of ghost and ghosting meant something different to the foxes, but still she meant to try.

So she lay in the darkness at the foot of the metal bench, where the glimmer of sunlight could not reach, and she would grow very still and those neurons of her brain that lived natural in her feathers would alter her camouflage, dull the iridescence, practice matching the exact hues and tones of the prison cell. Her natural camouflage was meant to show dark from above and light from below while flying, so it took conscious effort to do otherwise.

All while the Old Man talked to her about his memories of people and places she did not know and did not care about, and eventually mention the gloom and put on more lights, which meant taking slow-writhing white grubs that glowed and shoving them into divots taken out of the ceiling. By how he still complained of the gloom the Strange Bird would count her progress in becoming less and less visible.

“My eyes must be going bad,” the Old Man grumbled, but he could not afford to use more light, for the grubs would be food if the weasels grew more cunning, if his garden began to fail.

Then he would continue his sermon, as if a broken-down version of the chaplain in the laboratory, who would spend so much time in senseless talking to the animals.

“I am not the man I was. This place was different once. There are more people out there. All sorts of things out there. But I would not last without shelter. It takes someone younger, stronger. Someone who isn’t worn-out—and I know people will come here soon enough and wrest even this from me. And in the other direction there’s just desert and wasteland and nothing good. You should know—you came from there. And this was the town I grew up in, although none of it is left. They’re all dead now. Now it’s just me and the lizards and the weasels and a toad or two. And sometimes an intruder. And now you.”

The Old Man could mumble like this for hours, sometimes rant and rave and become other than what Isadora thought he was. But even this the Strange Bird welcomed, for she understood him better and better through this repetition and she began to know not just his speech but his moods, to recognize the self-inflicted wound at the heart of him.

A favorite subject was of the city that lurked so near beyond the dune. Whenever the Old Man spoke of the city, his tone would grow hushed and his aspect fearful and the Strange Bird would remember the shadow of the monsters she had sensed.