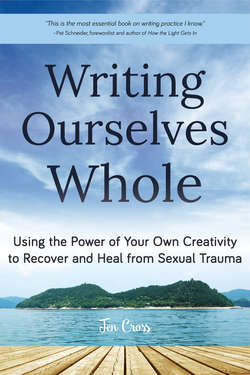

Читать книгу Writing Ourselves Whole - Jen Cross - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеhow to restory

To write is to enter the mess, is to spill out all your syllables, is to devil the precious eggs everyone else treads so carefully upon. Writing opens the wound, lets in oxygen and releases pus, helps me breathe again, I mean, breathe with gills & webbed toes, breathe against the tide that’s coming in, breathe through the mountains of fear I live within. To write is to enter the fuse, electricity on my lips, close the circuits, let sparks fly—to write is to see what I forgot I was thinking, is to be unstable, grammatically incorrect, metaphorically questionable. To write is to pass the words forward, to dance around old truth, to hunger with pen and ink, to kill him over and over, that he who is only saved by the unmentionings, the unsaying, the not speaking. To write is to tell about his mustached grin, the taste of his tongue, his grey belly—when I set these truths to paper, I make his monstrosity visible, familiar: one more regular old child molester. I lift up the rock he turned himself into when he lay upon me and reveal the white grasses, tiny bugs, balled-up roly-polies, ants, beetles with shiny stained wings—all the life still making a way down here.

Down here. To write is to go down, go in, to emerge with handfuls of something I smear on the page. I don’t stop to read, reflect, reinterpret. I just stain what was empty, secrete the silenced, and move on with more handfuls. To write is to mix up the wheat paste and poster the neighborhoods of my frightened inside corridors with noise & mess, to blur all the boundaries, remove and muddy the sharp crease between my good girl surface and the difficult things inside. To write is to lose track of identities, to loose tense muscles around neck, shoulder wings, belly, coccyx, thighs, to set vowels and variables into those muscles, transcribe a new calculus and slope new languagings for ease to ride itself upon into this swollen, unbreakable being.

This is what writing does. It marks up what we work so hard to make smooth, it pulls tight all the lines cast forth from within us, knots together past present future, opens space and time to release the brilliant catastrophe we were meant to be. Our skin, this singular organ, contains every possibility we ever laced with might have been and the writing sets all that possibility free, helps it step ginger or fierce into the world, to discover ourselves again. (2002)

•§•

Why do so many of us who have suffered something unspeakable turn to blank pages, pen in hand or fingers on keyboard, reaching for the words to describe, clarify, or explain what we’ve been through, even if only for ourselves, even when we never expect to share those words with anyone else?

If you have written about or out of a place of shame or loss or trauma, you have your own answers to this question. Since I began offering writing groups for trauma survivors in 2002, I’ve found that when survivors write the true and complicated stories of our lives, our perception of our lives expands, shifts, opens and transforms—and when we share these stories with our communities, we are no longer alone with the many secrets we’ve carried for so long. Other survivors listen to our writing and treat us like creative beings whose words have power and make a difference, rather than responding to us like the terrible people our perpetrators convinced us we were. That reception changes everything.

The writing fingers open the tight fist of power and control and drops us out the writing opens up a chasm the writing throws over a bridge the writing topples buildings, walls and boulders fall steam risesthe room opens. The body opens. The future opens.

•§•

As a writer, workshop facilitator, and survivor of sexual abuse, I’ve witnessed first-hand what happens when survivors create the space (on the page, in our lives) for the whole of our stories, especially the stories that stick in our throats, the stories that hide under our lungs, behind our eyes, between our legs; the stories we aren’t supposed to tell because our families don’t want to hear them and/or our communities can’t hold them with us—or at least we don’t believe they can. All of us who are trauma survivors know: there are the stories we tell and the stories we don’t tell. There’s the trauma story that we have rattled off so many times that it rolls from our lips in one continuous breath, so polished and packaged we can barely feel it anymore, the story that is neat and clean and careful not to make anyone too uncomfortable—and then, underneath that, are the messier stories of our violation and survival, the many stories we never tell anyone, the parts that are still raw and throbbing and sore, wounded and tender and fragmentary. These are the stories that don’t fit into a “good survivor” identity. These are the parts of ourselves that we’re sure will get us turned out of our communities: stories of the things we did to keep ourselves alive, stories we fear make us as bad as our perpetrators. There are stories of what we long for, the desires and hungers we hold under our tongues, afraid of what it says about us that we want anything at all. The carefully-rehearsed trauma stories are only the tip of the iceberg that is our complicated, tangled, gorgeous human self. When I talk about writing ourselves whole, I mean writing out of the undulant enormity under our smooth surfaces, in order to bring forth shards of our as-yet-unarticulated real stories and selves.

First Nations writer Thomas King, in his beautiful book The Truth About Stories, says, “The truth about stories is that’s all we are.” In my twenty-some years recovering from sexual violence, using writing practice as my primary medicine and splint, I’ve found that writing—first freewriting alone, and then writing with other survivors—is a way to give myself the language for the stories I believed couldn’t be told: the trauma stories I hid (or hid from), the desires I was afraid to articulate, the parts of myself and my experiences I trained myself never to speak.

•§•

I started journaling in 1993, when I was twenty-one years old and breaking away from my stepfather after nearly ten years of ongoing sexual, psychological, and physical abuse. As often as I could, I took refuge in local café, where I bought a large, dark roast coffee, and popped a tape into my portable cassette player—Ani DiFranco, Erasure, Zap Mama, The Crystal Method—slid my headset over my ears, folded the notebook open to a new page, uncapped my pen, wrote things I thought I’d never be able to say out loud. I spent years doing this, my butt planted in a wooden chair in some coffee house or other in Northern New England or around San Francisco. This is the way I found my tongue again. I wrote through the numbness that kept me protected—through writing I could feel the sadness, despair, depression, rage. The emotions had a weight and a shape once they found their way into words, whereas, inside me, they had all tangled together into a single inarticulate mass. There were few days I didn’t break through into tears while I bent over my notebook at that corner table in the back of the cafe.

In the earliest months of my writing practice, I was often rigidly and “logically” truthful. I froze often during my writing sessions, straining hard to get every detail right so my stepfather could not accuse me of lying (should he ever come to read what I wrote—and, of course, I assumed he would; up to that point, he’d had access to every single aspect of my being). I wanted to compile a record of his atrocities, and was beginning the work of disentangling my feelings from the so-called psychoanalytical brainwashing that was a core component of his control over me, my sister, and my mother. If he ever made good on his threat to have me killed for leaving his bed, I believed someone would find this notebook and finally know who I really was. In those early years, as much as for any other reason, I wrote to survive my death in the form of a final, true story. I had told so many lies—I wanted someone, in the end, to know What Really Happened.

I wanted friends and former lovers and family to read the story that explained me: this is why I was so sexually experienced so young; this is why I’d be locked in the bathroom of my dorm room on the phone with my stepfather for hours; this is why I had rabid mood swings; this is why I was such an erratic friend; this is why I disappeared. Oh, this was why Jen was so crazy all the time. This is what she was dealing with.

After a year or so of “just” writing, I managed to get into individual therapy. I participated in groups for women who were incest survivors. I spent hours wandering around my small college town, listening to music and crying. I drank too much, watched too much bad television, spent uncountable hours reading books about incest, feminism, sex. But it was when I sat alone at the Dirt Cowboy Cafe in that small town in New Hampshire, one hand affixed to a big mug of French Roast coffee and the other hand moving a pen across the page, that things—life, loss, longing—slowed down and unraveled enough for me to be able to breathe a little better.

In Writing Down the Bones, Natalie Goldberg said we should take two years focused only on writing practice before we tried to write for publication, so that we could learn the contours of our minds, our inner selves. I couldn’t imagine wasting all that time just journaling. Two whole years? Is she kidding?

I look up today and it’s been over twenty.

They weren’t relaxing, those hours with my journal. This was not a hobby or dalliance. I was learning to save my life. Writing came to be a way for me to be safely but intensely present with myself and with the world around me. Through writing, first and foremost, I (re)learned what it meant to be human.

•§•

This is the writing practice that has worked for me: write daily (or as near as possible), create open space for the words, keep the pen moving, don’t let the censor/abuser stop the flow of words (sometimes I write down the censor/abuser’s objections, when I can stomach it, just to get them out of the way), and follow the writing wherever it seems to want to go.

“Following the writing” means listening to the tug that wants me to write about my childhood dog or that moment of feeling triggered when I thought I was going to finally get to write about the sex I had last weekend. It means writing exactly the words that pop into my head—those first, often nonsensical thoughts—and trusting them, even if I can’t see where they’re leading. It means writing, word by word, into the terrifying places, always going slowly, listening to the deep wisdom of psyche that tells me when we are ready to go in and nudges me when we are ready to ease back out. I drop my pen to the page and go, trusting that I won’t be the same on the other side. French feminist Hélène Cixous, in her brilliant essay “The Laugh of the Medusa,” wrote, “When I write, it’s everything that we don’t know we can be that is written out of me, without exclusions, without stipulation, and everything we will be calls us to the unflagging, intoxicating, unappeasable search for love.” That’s what I mean.

When I started journaling in cafes back in the early ‘90s, I wrote fast and messy. Fast, because I wanted to catch those first thoughts as they came to me. There was no time to slow down—I needed to grab the thought and get it on the page right away because the stepfather in my head was sure to contradict, challenge, or change it. I learned to catch those thoughts and write them, too. I wanted all of it on the page, so I could look back at it later, so I could record all the madness in my head, so I didn’t have to be all alone with this overwhelm anymore. The page could help me hold it. I wrote messily so that I could write anywhere—in public, at the coffee shop—without worrying that the people around me could easily read over my shoulder. I was afraid of being found out, yet I couldn’t write at my apartment. Home wasn’t a safe place, no matter that the physical danger lived 1,400 miles away. At the cafe, I couldn’t hear the phone ringing, reminding me that he was (I feared) never going to stop monitoring me, never going to stop harassing me, never going to let me live my life away from him in peace.

I had a whirlwind in my head. I wanted to get it all down before I forgot, or lost the thread, or lost my nerve, before he came to take me back. I was sure he was going to track me down and make me go back.

In order to concentrate on writing, I needed noise outside to counteract all the noise inside, to soothe my hyperarousal and an overdeveloped startle response, to get to what Stephen King calls “the basement place” out of which to imagine and create. I needed a crowded cafe, loud music in my headphones, and my back to a wall, face toward the door. No one was going to sneak up on me while I wrote this history, while I wrote into the contours of my trauma. It took a great deal of effort and energy to be able to focus my attention at all. I wrote stream-of-consciousness (I have whole notebooks that are run-on sentences), fragments, flash images, and filled the page with shout-and-scribble when I was too angry to form words at all.

Over time, by following the thread of my writing right into the now, the now became a place that’s safer for me to inhabit while I’m writing, even without all the distraction. Slowly, over these years of writing practice, I have come to be able to write even with no headphones on, no longer terrified of my startle response, no longer afraid of something bad happening to me when I get lost in the words.

•§•

Creativity is in us. Creativity is us. We who are survivors of intimate violence are always creating, given our ability to adapt to horrifying, unendurable situations. Without a profound creative capacity—our instincts and intuitions, the generative resource of our resilient psyches—we wouldn’t have survived our homes or relationships or any of the other war zones we’ve endured. We couldn’t have navigated the impossible landscapes laid before us. We wouldn’t have been able to read the emotional street signs in our families, develop strategies for disappearing and reappearing inside our own bodies, or negotiate the simple, daily horrors of living with an abuser. Trauma and creativity are inextricably linked, and, I believe, creativity can pull us through the after-effects of what was done to us, and what we did to survive.

Changing our language, shifting our story even slightly, alters how we know ourselves. We are elastic beings ever becoming new. When we name what we have experienced—especially when we were told that no one would listen to or believe us, or when we were not taught the words we’d need in order to tell—we take power back from those who meant to silence us, and we reclaim control over the narrative of our lives. When we question, reword, or invert the stories we learned to tell about our ourselves, we are changed—we begin to be restoryed.

•§•

We are made up of the stories and memories we lift out of our pockets to share with friends over dinner, the remembrances we recite for ourselves in the thick of depression or in the bright morning of recovered joy, the stories we draw from film and TV commercials and pop songs and novels and Saturday morning cartoons, the anecdotes and gossip we heard our mother and aunts telling across the table at holiday suppers, that our fathers and uncles slipped through the sides of their mouths while watching the game, the stories that we saw whispered and pantomimed. We are shaped, too, by the stories we keep hidden. We were shaped by the stories our perpetrators told themselves and us, in order to justify their violence, and by the stories we told ourselves, in order to make sense of the violence we were suffering through. We were shaped by the response when we told what had been done to us: whether we were heard and cared for, or denied and shamed. The stories we grew up within determined what we experienced as possible—and impossible—for our lives.

There are stories that serve us for a lifetime. And there are stories that serve us for a period of time and then begin to harm us. Often, though, we don’t notice that shift until we are in some kind of pain. Questioning our stories is risky and frightening. Who am I if I’m not this person I’ve been telling for years? What do I mean if my foundational stories are malleable?

When I began to lead writing groups with sexual trauma survivors, I finally thought to ask: What happens if we question the mainstream stories that get told about us? What happens when we tell the untellable stories? What if we challenge the stories our families or perpetrators or communities told about us, the normative, normalizing stories that tell us who and how we’re supposed to be? I wanted to find out what happened when we wrote directly into the stories we were most afraid or ashamed of, when we turned our most-told stories upside down and inside out. What happens when we write the backside of the stories we have internalized about ourselves, about our communities, the stories of our healing or our desire?

In writing with groups of survivors (and other folks, as well), I found the strength and curiosity to write into and question some of my most deeply-held stories (that is, beliefs) about myself: that I was broken; that I would never feel safe in my body; that sex would always be difficult for me; that I was a failure; that I didn’t deserve to call myself a woman; that I was culpable for my stepfather’s sexual abuse because I hadn’t been able to stop him for so long; that I didn’t deserve family; that family didn’t want me; that I wasn’t worth caring about or saving. It takes heart and guts to tell the truth on the page, whether we ever share that writing with another soul. We grow, we transform, when we are willing to take that risk.

If we as a culture are immersed in story, then it follows that we come to know, to understand, ourselves through story. Therefore it’s possible to be transformed by others’ stories, by others’ ways of knowing and experiencing the world and their own possibility, though this requires a profound vulnerability and willingness to be open to change. When we are present with other people’s stories, we can learn different ways of looking at the world, looking at ourselves, understanding pain and struggle and desire and longing, than we ourselves have yet considered. I notice this happening quite often in the writing workshops, a note of, “I never heard it described quite that way before—that’s just how I feel, too!” And there’s a shift, a splitting open, a new openness of our perceptions, and thus ourselves.

There is a quality of magic that manifests when we gather with others in community and share our creative selves. The word magic comes from old Greek and Persian words that have to do with art and agency or power. I want that magic—that powerful art—for all sexual trauma survivors, because I believe this work can heal us, break open our isolation, reincorporate us into the human family, while transforming humanity into something more kind, expansive, and real.

•§•

One magic quality of story that I most value is the way stories show up for me when I am most alone and nearly lost. Dr. Rachel Naomi Remen, the author of Kitchen Table Wisdom, was one of the facilitators I worked with when I attended the Writing as a Healing Art conference in 2010. While she was with us she discussed the power of story, describing the ways in which stories are able to accompany people into their darkest places. The story that any of us tells about how we survive our own struggles will accompany those who’ve heard us when they, later, have to walk into their own difficult places. The listener receives these stories as a kind of opening, a faint and terraced map: Look how they resisted, made it through, forgave themselves, told the truth—maybe I could do that, too. I carry workshop writers’ stories with me: they live along the skin of my forearms, they live in the cilia just inside my ears.

When I hear others’ stories of resilience and resistance, I get the chance to revisit my own narrative, reconsider the parts I’ve labeled cowardice, betrayal, isolation, lack of integrity, lack of strength, and cover those old labels with sticky notes on which I’ve scribbled: strategy, resilience, patience, courage, generosity. I try on new naming. I remember, in the early 90s, sitting at an isolated desk in the dusty stacks of my college library. The timer that controlled the light above the study area ticked away while I flipped through an old collection of women’s stories of abuse—maybe it was I Never Told Anyone—horrified that this was happening to so many of us, and, underneath that, so thankful to have discovered I wasn’t alone. I don’t think I ever checked that book out; I was too afraid of the librarian cocking an eyebrow my way, which would lead inevitably, I was sure, to my stepfather raging at me on the phone because I “told.” But there in those stacks, when the timer ran out and the light clicked off, I held the book in my hands for a moment, breathing in the knowledge that there were women who made it out—that there were women who got free, that there were women who told.

We need one another’s’ stories as we learn to navigate the world post-trauma. For anyone struggling with the isolation of trauma aftermath, writing authentically—alone and with peers—can be transformative. Author and essayist Barry Lopez says, “The stories people tell have a way of taking care of them. If the stories come to you, care for them. And learn to give them away where they are needed. Sometimes a person needs a story more than food to stay alive.” While we can never change what was done to us, we can transform how that history lives in us, take control over how it shapes and constrains us. We can come to understand that creativity, or creative genius, or possibility can be our name: broken and raped don’t have to be our names. Victim doesn’t have to be our name (nor does stupid or shithead or selfish or crybaby or coward or whatever other words they used against us to keep us tethered, afraid, and ashamed).

We can allow these experiences to take up a right-sized space in our souls without them having to be the whole of our being. We can story ourselves anew.

•§•

We who are survivors of horror—of sexual violation, of physical abuse, of mental torture, of emotional manipulation or disregard, of captivity; those of us who’ve had ties with our own blood severed, or who have wished to scrape out of our veins the blood that flowed there—who are we, without the roots of a shared (hi)story? We’re not the first generation of survivors, we’re not the first generation whose parents/caregivers/spouses thought we were worthy of abuse: part of our lineage is that truth, borne forward in the mouths of the ones who came before us, in the whispers and models of resilience, in the slow ways we learn to keep little pieces of ourselves safe. No one told us outright how to survive: that knowing is bone-deep ancestral memory, something in these cells that knows about staying alive when everything else says die.

We are of our own blood, true, and we are also of that other, larger family, the family that will never gather for a reunion, that averts its eyes from strangers or looks boldly into your curious face, the family of truth-veined human beings who made it through something horrible, only to have to live the rest of their lives carrying those memories in body and breath.

In this book, I mean to constellate some of what I’ve learned in twenty-some years of ongoing personal writing practice and over thirteen years facilitating sexuality and other writing groups with folks who, like me, survived sexual violence in one form or another. Throughout, I describe why I believe writing alone, and in a community of peers, is so revolutionary for sexual violence survivors.

The process I describe herein, that I’ve been working with for the past many years, has three parts, each of which can crack us open to transformation: story, voice, and witness:

• When we find words for our untold stories, we build new relationships with the fragments of experience, memory, and reaction that have bounced around inside our psyches with no tethering, no root; we allow the stories out of our bodies and into the world.

• When we read aloud our new writing, we give voice to both our story and our creative abilities, and we deepen our embodiment as writers and speakers.

• When we choose to share our work with others, we are witnessed: we hear how our writing, our craft, our story has affected others; our story isn’t ours to carry alone anymore. We get to experience being truly heard and we get to return that kindness by listening to/witnessing others’ stories as well. We come to understand that our attention is important, that our listening and observation matter.

•§•

In those first months and years of this writing practice, it felt like I was running for my life with words, and if I stopped to think too hard about what I was saying, I clotted up in doubt and fear and couldn’t write at all. I needed the right kind of pen (Pilot Precise v7) and the right kind of notebook (8 ½ x 5 Artists Sketchbook, please); I needed the right noisy cafe, a corner table near the window, headphones and a cassette tape of music I knew well. I needed many cups of strong coffee adulterated with a lot of sugar. I was like that little girl, afraid of the dark, who needs a glass of water, and her blankie, and the same two stuffed animals, and the door left open just the right amount before she felt safe enough to fall asleep. Everything had to be just right for me, too; I was absolutely afraid of the darkness I was trying to write.

My stepfather had tried to occupy every fragment, every nook and cranny, every inch of my psyche—he believed, and trained me to believe, that he had a right to every thought in my head, every emotion, every instinct. He taught me to believe he (or someone in his employ) was always watching me, and through this training, taught me to surveil myself. A legacy of that surveillance took the form of brutal and byzantine inner critics who contradicted or challenged most of what I thought or wrote. So I learned to write very fast, in order to outrun these challengers—by the time the voice rose up to take apart an accusation I made on the page, I was already onto the next line.

The chatter of the other cafe patrons, the music pulsing loud and fast through the headphones: these occupied my hyper-vigilant consciousness, so that I could write from the place underneath—from the self that was terrified of exposure, from the well of knowing that had been forced into silence during the years my mother had been married to my stepfather.

At first, I used the pages to try and make sense of myself—quite literally. After finally escaping my stepfather, I first tried to write down—using the direct, clear, logical language my stepfather had demanded—all that I had been through and was feeling. But the words kept getting muddled. I stopped writing in the middle of a sentence, stuck between what I knew was true and the quarrelsome voice of an inner censor, which sounded an awful lot like my stepfather and challenged almost every assertion I tried to make about what he’d done. I stared out the window at my hale and happy-appearing classmates; why didn’t they have this trouble? I’d lived so long inside the silence, and tangled in the Doublethink and Doublespeak, required of those surviving long-term abuse that I no longer knew how to speak straight-forwardly. My stepfather had forced me to dismantle my own language and desire from the inside out, and reconstruct these in the image he preferred. I didn’t know what anything meant anymore. That’s not exactly true; I didn’t know how to convey the layers of meanings inside my words to anyone else.

After I told my stepfather that I could no longer “continue our sexual relationship” (that was the language he required us to use) and broke contact with him and the rest of my family, he promised to harm or kill me and those I cared about if I told what he’d been doing. So I did not go to the police and I did not go to therapy. The trajectory of my life upended. He and my mother terminated their financial support for my education, so I had to withdraw from school after the fall of my senior year. I took a job with the on-campus library, went more than a little crazy, drank almost anything I could get my hands on, watched too much Rikki Lake, and wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote. It took almost a year after that terrifying conversation with my stepfather before I could let myself believe that I would not be physically harmed if I told my story to a therapist, and by the time I was able to so, I’d already developed the writing practice that I would use to suture myself back together.

In working to heal the damage my stepfather did, I haven’t only written, of course. I also, as I mentioned above, went to talk therapy, as well as group therapy, feminist support groups, model mugging and self-defense classes, every modality offering tools I could use to further my healing, my sense of sanity. But my mother and stepfather were both psychotherapists: I understood how the language of talk therapy could be used to undo or contort or ensnare someone’s psyche and sense of self—and though I have worked with kind, smart, wise and generous therapists, I don’t know if I have ever fully trusted that process or relationship, though I do believe in its transformative potential. Writing, however, has been a steady and unwavering companion, able to listen and welcome without transference or countertransference.

The page has been the place where my whole self could emerge—my complicated, confused, petty, sorrowful, funny, jubilant, desiring, hopeful, despairing, pleased, depressed, hurt, enraged, spiritual, philosophical, playful, curious, certain, and uncertain self. The page introduced me to my human self—utterly imperfect and nonetheless acceptable. The page has been a place for beauty, for grief, for attempt, for starting over. And over. And over. And over. Freewriting is my yoga, my daily jog, my meditation, my spiritual practice—when I go without this writing for too many days in a row, I begin to lose touch with myself, become jagged and short-tempered; I can feel, inside, the shards of me banging against each other. I am too many pieces again, all of them demanding attention, demanding to be true. My sense of wholeness begins to disassemble when I fall out of this practice. I’m cranky, less pleasant to be around, less functional in my so-called adulthood.

People dismiss writing practice as “just journaling.” I just did so when telling a neighborhood woman about what I was doing here, sitting in the sun across the block from my city’s beautiful lake. She’s been watching me here. She’s small, slender, brownskinned, her hair cropped close to her scalp, wearing Bermuda shorts, a blue T-shirt, and green glitter flats. Her male companion is across the street, sorting recyclable cans and bottles, preparing the many bags to take to the recycling center. She comes over to me and says, “You must be doing schoolwork or something.” I say, “I’m just journaling.” She says, “You must have a lot on your mind then.” I want to invite her to sit with me and write. I know she also must have a lot on her mind. The man across the street makes a noise in his throat when I comment appreciatively on the woman’s shoes, and I am worried that any more kindness I show her will result in some kind of challenge from him when they’re alone. (I never wanted anyone to say anything nice about me in front of my stepfather for the same reason.)

Just journaling. I don’t say, I’m continuing to teach myself how to breathe into this lifetime. But, for me, that’s what this practice really is.

•§•

Over time, my requirements for my writing time loosened—maybe I could go ahead and write if I only had a cheap ballpoint pen. I shifted from expensive unlined artist’s sketchbooks to the cheap single-subject notebooks that I buy in bulk every August when school supplies go on sale. I began to be able to write at home, and, eventually, my startle response softened enough so that I could write in silence—no longer afraid of being heart-poundingly surprised by any sort of noise when I was deep in a write.

Writing groups helped me learn to write under conditions that weren’t entirely under my control. More importantly, though, is that, throughout, I’ve worked to give my writing what the writing needed. For so many years, I was trained to believe that others’ needs were more important than my own, that my creative or intellectual needs (to say nothing of the need for safety and comfort) weren’t worth respecting. In my stepfather’s house, if he was in the middle of working, he was not ever to be disturbed; woe to any of us who broke his concentration. Yet, of course, no matter what my sister or mother or I were doing, when my stepfather decided he wanted our attention or bodies, we were expected to be available to him.

After leaving his house, I came to be selfish in my work, to take my time back for myself and this practice.

Now, I’m in my apartment, writing this in a twenty-minute window just before a workshop is slated to begin. I put on a little Irish fiddle music, and I drop in to the writing. That’s a miracle, when I stop and think about where I began, and is in part the result of these years of practice and patience, the result of giving myself years of care and structure—all the pieces in place just right as I taught myself it was safe for me to go into the dark, to find those stories still hidden, still isolated, still lost.

•§•

Think about how powerful it is to share a story, a necessary story. There are stories that live in me as a broken kind of breath because they haven’t yet received the reception I need for them, a sense that they have been truly heard, understood, grokked. Former Poet Laureate Kay Ryan, at a Granta reading at Book Passage in San Francisco in the fall of 2012, talked about the work that the reader agrees to when she chooses to engage with a poem. Ryan said that the reader is part creator, part inventor, of the poem—without reception the poem has only done half its work. We need a listener/reader/witness to complete the process of storytelling or poem-making.

Story. Voice. Witness.

This process is so simple, and yet its impact is radical: Using a freewriting practice, we can take our creative transformation—and therefore our healing, our lives—into our own hands. We as communities have the ability to hold, welcome, and help reframe the difficult stories that keep individual community members feeling isolated and outside the fold. We don’t have to relegate one another to the isolation of the therapist’s office, and neither do we have to fix each other: we engage a healing practice when we language our true stories, when we share honestly with others who can hear us, and when we demonstrate that we are willing to listen and be present with one another.

This is a book that has sexual trauma survivors at its heart, but this practice of story, voice, and witness has made a difference in many people’s lives, whether they identify as trauma survivors or not. I can’t think of a group of folks or a community who wouldn’t benefit from engaging together in this kind of generative, generous, shared creative community. Veterans, frontline crisis workers, PhD candidates, couples, sexual violence survivors, folks just coming out as gay or queer or trans*, survivors of genocide, teachers, coworkers, adoptees, refugees, foster kids, gender nonconformists, those folks of color who daily navigate white supremacy, religious communities, nurses, doctors, therapists, single parents … we all have stories we want to tell, stories we feel silent and isolated around. There are none of us who haven’t spent time living at the intersection of trauma and desire, and the stories at that intersection are stories that define us.

Many books have been written about the power and use of writing for individuals who want to heal. This book joins that lineage—another invitation to you to write your story because your words are necessary magic. We need our mainstream narratives about rape, incest, as well as those we tell about the survivors of these violences, to be complicated, messy, and thereby made more real. We need all the stories if we as a society are to learn the truth about intimate violences, and if we are to undermine and transform the conditions necessary to allow those violences to continue to run rampant in homes around the world.

This is not a how-to manual or a guide or a workbook. This is a love letter, a series of stories, an exhortation. Like author and memoirist Lidia Yuknavitch said when she spoke at the Association of Writers & Writing Programs Conference (AWP) in 2015, I am here to recruit you. This book is a revelation and a hope. This is how I did it and how I think about things, one more piece of the conversation about what writing can do for us whose bodies and other parts of ourselves have been fragmented in various ways by intimate and/or sexual violences, offered in fragments, small essays, long rants, curiosities, listicles, and prayers. This is some of what I’ve learned and thought about after writing myself (more) whole these twenty-four years after escaping my stepfather’s violence, and after writing with hundreds of sexual violence survivors (and others) since the first queer women survivors erotic writing group I convened at the San Francisco LGBT Center in the summer of 2002.

•§•

I have structured this book as a collection of short essays: you can read the whole thing straight through if that’s your way, or you can drop in to different sections randomly, open the book and see what has chosen you today. Read to be inspired, read for prompts, read for ideas or possibilities, read for challenge or to argue. This book is meant to be consumed however you prefer. Go front to back, back to front, skip around, or begin in the middle, read to the end, and then go back and finish up with the beginning. There’s no wrong way to do it. Though a collection of writing prompts appears in the Appendix, I consider this whole book a spark for your writer’s imagination, and the beginning of a conversation. If you find yourself responding strongly to what you’re reading, I invite you to put the book down, pick up your notebook and pen, and write whatever is coming up for you, what you’re agreeing with or pissed off about, how you wish I’d said it differently or how you’re surprised by a particular phrasing or consideration. You’ll notice that I sometimes drop into poetry (as at the very beginning of this chapter)—much of this book was generated in freewrites, either in my journal, for the Writing Ourselves Whole blog, or in writing groups, and I include these more poetic pieces as examples of what can emerge when we let the pen go where it wants to go. First and foremost, I want to convey the power of writing for deep inner change, and, more than anything, want to encourage that small, quiet (or clamorous!), persistent part of you who just wants to drop everything else and write.

My invitation is to let yourself write slow. Write your story in chunks, in stages, in fragments. Respond to writing prompts. Do this for a month or six months or three years, every day or most days. You certainly won’t (nor do you need to) write about trauma every time you pick up the pen (and any time I write, “Pick up the pen,” please add, “or place your fingers on the keyboard”). Your story is more than trauma—you are more than trauma. It’s good to give yourself permission to write anything. Turn your writer’s eyes away from the images at the back of your head and toward the flowers just blooming in your neighbor’s window box or the taste of a ripe peach or the daydream you had about the bike messenger you saw flying down Market Street on her fixie while you sat on MUNI waiting for the streetlight to change.

•§•

The essays in the book are gathered into five sections between this introduction and the conclusions: Initial Preparation, Story, Voice, Witness, and Self-Care. These sections aren’t strict confines; more like loose collectives, or affinity groups—you’ll see a lot of overlap in themes and ideas throughout.

In Initial Preparation, we begin to lay the groundwork for our writing practice, what it means to write ourselves whole, and why we would ever want to try it.

The Story essays tangle with the work involved in finding, finally, the language for the unlanguageable: the unspeakable, the unspoken, and the unheard. It has to do with deciding to find the words for the stuff we were told would never be believed. This is the part where hands are on the page or keyboard, the alone work part, the communion with self, finding words for embodied and disembodied experience, and dis-ordering what has been sanitized, made too neat and nice so that others listening will be comfortable.

In Voice, we get into what it means to take our narrative back for ourselves, to say (in writing and out loud) what we were never supposed to say, and to allow our bodies, finally, to “speak” those stories that they have held for so long.

The Witness section contains writing about creating and sustaining a peer-led sexual trauma survivor writing group: what happens when we write together, how to navigate some of the challenges that arise, how to sustain yourself and your group.

In the Self-Care section, we think about both how to use writing as a self-care practice, and how and why to take care of ourselves as we write these beautiful and difficult stories of ourselves.

The Conclusion essays aren’t terribly conclusive—more like launching pads, explicit invitations to begin now, and then begin again and again, to find words for your own stories: as poetry or prose, as fiction or testimony, in any form you wish, and write yourself complicatedly, messily, fragmentedly, gorgeously whole.

•§•

Please take care of yourself while you read, and while you write. There’s explicit language about sexual violence, and about living in the aftermath of trauma, in these pages. Please be easy with yourself as you read, stop when you’re uncomfortable, and write when you feel drawn to write. You have enough time; please don’t feel you need to rush yourself to get it All Done Now. Think about ways you can take care of yourself during or after your writing, and consider how to be kind and gentle with yourself during this time, how best to receive the support you’ll want, and make some mental plans for that.

Some ideas for self-care: call a friend who can listen to you without trying to “fix” anything; talk to a therapist; go for a run; punch a pillow; journal at a café (maybe treat yourself to an almond croissant, too); call someone from your writing group; play with your dog or cat or ferret or another animal in your life; visit the ocean at high tide and yell along with the thunderous waves; make chocolate-chip cookies or a big batch of buttered popcorn; prepare a whole meal that tastes good and feeds you well; rest; put on your favorite music while driving and sing along at the top of your voice; look for four-leaf clovers; go dancing; take a hot bath; write in your journal; snuggle with stuffed animals; spend an hour in the sun with a good book; take a “nature bath”—that is, a walk somewhere that you can be immersed in nature; garden or find another excuse to dig your fingers into some dirt; watch the birds; smell the roses (really!); bake bread; make yourself a cup of strong tea or just exactly the sort of coffee you prefer; go for a bike ride; binge-watch a ridiculous TV show; find an old movie that is sure to make you cry, and then one that makes you laugh…

This is just a beginning, of course. What else is on your self-care list?

•§•

What I hope for every single person reading this is that you write: if not inspired by the words, then by the energy behind them. Writing has saved and changed my life. May it do the same for you. Begin now to write yourself whole. Gather your own circle of writers in which to share your stories. And throughout, please, be easy with you.