Читать книгу Up the Hill to Home - Jennifer Bort Yacovissi - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBuilding 741

1893

The plan leaps out of the gate like horses at the track. The owner of the land is willing to hold the note, and recommends an architect, F. H. Kemght. In a happy coincidence, the builder that Charley plans to hire—George Dove, a childhood friend of his older brother Clarence—works with Mr. Kemght on a regular basis. Together, Charley and Emma sketch out the initial drawings, which Mr. Kemght refines into blueprints, and George fills in with the particulars needed to build the house. As the project evolves, Charley and Emma find that they work together well: their tastes are similar, they often see the same issues and possibilities, and each is willing to listen to the other when there is a difference of opinion. Eventually, Charley stops being surprised at how quick a study Emma proves to be concerning the ins and outs of designing and building a house.

This same partnership proves to be true in the matter of finances. Maybe if either of them had any acquaintance with how other people’s relationships work, they would realize that money is not something that couples talk about. Unless she comes from a wealthy family, a girl typically doesn’t have any money to speak of, and her intended doesn’t speak of his at all, either before or after the wedding. Even if Emma and Charley realize any of this, it doesn’t change anything. Neither of them harbor any romantic notions of the life they are undertaking; they need to be practical, and so they are.

Charley lives a frugal existence, and has saved since he began earning pocket change by threshing neighbors’ fields or mucking stables. But Emma more than matches him in parsimony, and has a head start on him when it comes to savings. Because they aren’t yet married, official paperwork demands that only one of their names show up on the deed, and because Emma is the one with the most earnest money to put down, hers is it. The landowner, Mr. Groff, is somewhat taken aback by this—even though plenty of surrounding acreage is held by women—but the check is good, which means the money is green, and that is all that counts. They work with Mr. Groff’s attorney to set up a monthly payment plan that will eventually account for the full four thousand dollars plus interest that the lot costs them. The day they sign the final papers and officially become landowners, they celebrate by having a supper of cold chicken, potato salad, and apple-filled ebelskivers while sitting on a felled tree trunk near the front of the property.

The light of the spring evening is growing softer. Charley, his dinner only partially eaten, cannot stop scanning what is now his small piece of the earth. He paces in the clearing near the stump, and every so often puts together the steps of a little jig when he feels that he might otherwise burst. He is overwhelmed by a sense of pride that even he has not anticipated. “Oh, Emma, think of it! We’ll put the vegetable garden over toward the southeast—good sunlight but not blazing hot in the summer—some fruit trees, flower beds in the empty spots. I know you’ll like that, won’t you? The house goes right here; we’re practically sitting on the front porch! Since it’s close to the street, we’ll need to put in a little fence—something low so that it’s friendly but still lends the necessary separation.” He finally pauses, and lets out the long whistle of a happy man. “Can’t you just see it?”

The truth of the matter is that Emma can’t see it at all. She hears the words, and the excitement in Charley’s voice, but she is unable to cast a vision in her own head. She finds this is true whenever she attempts to picture her future as it now presents itself. She is to be a married woman, the mistress of her own household, with a home and land that belong solely to her and her husband. Husband. None of these ideas resonate with her; after all, half her life has been spent in the certainty that these outcomes are unavailable to her. Picturing them has been pointless, even painful, when her future seemed fixed and unchangeable. Now, almost every day brings experiences she has never imagined, and she remains incapable of anticipating them. Sharing supper with her fiancé at the edge of their newly purchased property is but a small example. So she just smiles at Charley in his overflowing ebullience. “It’s enough that you can.”

cd

Mr. Warner is a reasonable boss, fair and willing to look out for his subordinates, as long as they are punctual, put in a solid day’s work, and remain respectful. He is among the many in the office who wonder aloud at the turn of events that sees Emma with a young man and an obvious intent to get married, quite beyond anyone’s concept of feasibility. Mr. Warner can’t wonder aloud among the office staff, since that would be fraternizing, so instead he shares with his wife the story as it continues to unfold. He can count on her eager attention to each new detail and periodic exclamations of amazement as he recounts the most recent developments.

Mr. Warner’s agreeability makes it much easier for Emma to apply for the permit than it is for Charley, whose own boss Mr. Grimsley would never allow him to take leave during work hours, which is the only time the permits office is open. Mr. Grimsley communicates primarily in growls and barks, and sometimes in a full-fledged howl. The men in the shop presume that he hopes this management style intimidates his subordinates enough to keep them from noticing his thorough incompetence; the strategy is unsuccessful. “Old Grim,” they say when they hear him gearing up again in the distance, “like nails on a blackboard.” Charley chuckles and says, “Like sand in your boots.”

And so it is that Emma asks and Mr. Warner gives his permission for her to leave the building for an extended midday lunch break so that she might apply for a building permit. She arranges in advance to meet George at the service counter of the office of the Inspector of Buildings to make application. A very pleasant older gentleman named Mr. Raymond meets with them to fill out the paperwork. George hands him a copy of the deed and a set of blueprints, and they walk over to a large drafting table that allows Mr. Raymond to unroll the plans; a leather-encased weight holds down each corner as he begins to fill in the permit form. From her vantage point, Emma is reading upside down, but she can still follow along.

APPLICATION FOR PERMIT TO BUILD

Brick and Stone

Washington, D. C. May 15 189 3 .

To the INSPECTOR OF BUILDINGS:

The undersigned hereby applies for a permit to build according to the following specifications:

1. State how many buildings to be erected: one

2. Material: frame .

3. What is the Owner’s name? Emma L. Miller

Mr. Raymond looks up quizzically. “My name is on the deed,” Emma says, and nods toward the paper in front of him.

“So I see.” He looks back to the form, and reads snippets aloud to himself in order to keep his place. “Architect...Builder...Location.” His finger traces down the top sheet of the blueprints until he finds the notation. “Lot 8, Block 22, northeast corner Flint and Eighth Streets, Brightwood Park.” He looks up at Emma and smiles. “Oh, that’s a lovely area.” He continues on. “Purpose? A dwelling...One family...26 feet front...28 feet deep...two stories...brick foundation...shingle roofing.” He pauses for a moment, looking from the form to the plans and back again. “Hmmm. Flat, pitch, or mansard roof?” he asks himself.

“Well, it’s not flat and it’s not mansard, so I guess it’s got to be pitch,” George offers. “It’s pretty steep.”

Mr. Raymond smiles again. “Steep it is then. What means of access?”

“To the attic? We plan to put in a scuttle.”

“Scuttle,” Mr. Raymond says as he writes. His finger traces through the remaining questions, some of which contain words or phrases unfamiliar to Emma: what is an oriel? He draws a wavy line down through all of them, with the exception of, “What is the estimated cost of the proposed improvement?”

He looks up at her as he asks, and she realizes that she does not know the number that George and Charley have settled on. “Two thousand dollars,” George says, and Emma coughs in order to cover up a small gasp. She isn’t sure what number she has been thinking of, but it is not that.

Mr. Raymond scans the form one last time as he straightens up from the drafting table. Apparently everything is in order. He looks at Emma again. “That will be two dollars for the application.”

Emma feels herself flush hot in a wave of panic. She hasn’t thought to ask about a fee—why hasn’t anyone mentioned it before?—and she knows she does not have that much money with her. She is so mortified that she almost doesn’t see that George is already pulling the bills from his money clip to give to Mr. Raymond. “Thank you. Now, Miss Miller, I just need you to sign here on this line.” He dips the pen, taps it against the neck of the inkwell, and hands it to her. Her hand is shaking, but she manages not to smudge the ink as she signs. He takes the pen from her and dips it again. “And Mr. Dove, here,” he indicates. Then he blots the signatures, holds up the application to look at it one last time, and says, “If you wait here, I’ll be back shortly.”

“I don’t have time!” Emma cries out before she can stop herself. On top of her surprise at the cost of the house, and the embarrassment about the application fee, Emma has been watching the wall clock with increasing apprehension. She can’t count on Mr. Warner’s goodwill extending into the afternoon; she needs to get back to work.

“Mr. Raymond, you don’t need Miss Miller to sign any other forms, do you? I can wait for the permit myself.” Mr. Raymond nods, and Emma breathes, “Thank you,” quietly to George. She bids goodbye to Mr. Raymond and slips out the door, forcing herself to slow her steps as she walks back to the office. By the time she reaches the entrance, her composure is restored. She tidies her hair a bit, walks the two flights upstairs, and slips back into her chair.

By that evening, the episode has lost its sting to the point that she is able to make light of it during dinner with Mary and Charley, and again when George comes by the house. “When Mr. Raymond asked for the two dollars, I feared for a moment that I might faint.”

“You did turn a bit pale there, Miss Emma. I’m sorry I forgot to tell you that I pay the application fee. But this might make up for it.” With a flourish, he produces an envelope and hands it directly to Emma. She opens it and shares it with Charley as they take it in together.

No. 2357

PERMIT TO BUILD

---

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR OF BUILDINGS

Washington, May 15 189 3

This is to Certify, That Emma L. Miller

has permission to erect one 2 story brick building on lot 8

Blk 22 Brightwood Park, Cor 8th & Flint in accordance

with application No. 2357 on file in this office, and subject to the provisions of the Building Regulations of the District.

She and Charley continue to admire the document long after they have finished reading it. In his happiness, he reaches over and squeezes her hand, and she responds with a smile. Charley folds the paper back up to look at the outside. The back of the document indicates that this permit had been recorded in the County Building Book, No. 13, Page 209. He flips it over to the front, and both he and Emma notice simultaneously. She gasps and Charley holds the document out to George. “This says the permit was granted on the eleventh. Today’s the fifteenth.”

George looks at it, surprised, and then lets out a good-natured laugh. “Well, whoever said that Government clerks aren’t efficient? Here they approved the permit before they even got the application!”

cd

A hawk circling high overhead—in this region, almost certainly a red-tailed or red-shouldered hawk—wheeling effortlessly in the warm updrafts above the open farmland of Washington County, might notice, among the irregular and haphazard plots of cultivated farmland and uncultivated fields, a tiny grid superimposed on the land, an unnatural series of sharply defined squares stamped into the countryside. If such a hawk were to circle in for a closer look, it would soon resolve that the grid is formed by roads, to the extent that raw graded strips of land can be called such, that start and end abruptly for no reason that its hawk eye can discern, since, after all, man-made boundary lines are visible only on maps, not stitched into the countryside. Its curiosity piqued, it winds closer and closer to earth, until it glides past a sign that clearly states, “Welcome to Brightwood Park.” Accepting the invitation, it selects one of the few trees in the grid to survive both farmers and land developers, settles in, and takes a look around. It considers that the food supply might be good here, since the land inside the streets still houses undergrowth of tangled brush, evidence of farmland that has lain uncultivated for some years. Finally, the hawk notices activity in one tiny section: hacking, chopping, a dragging out of vines and brambles. There’s no need to hear it to know that under it all is the manic skittering of tiny, clawed feet, their owners shocked to be revealed in an instant naked to the world, and now scrambling for cover. Eons of instinct cause those red shoulders to contract automatically in preparation for flight, as an electrical pulse sends the signal: Dinnertime.

cd

Once the land deed is recorded and the building contract signed, Charley wastes no time. He and George have negotiated the price of the house based on the understanding that Charley is to contribute a significant amount of sweat equity to the project. It’s also agreed that, if necessary, the house on Flint Street will take a back seat to George’s other projects. The work will take longer, but the cost savings are worth it.

Evenings after work, when it’s dry, Charley is out at the property. Every weekend, he has teams of helpers with him, at first clearing, then grading. Some of Charley’s brothers come in from here and there, along with Joe and the other fellows from Mrs. G’s boarding house, even Mrs. G herself, armed with tea, lemonade, and lunch. Emma does not hang back, but ties up her hair in a handkerchief, pulls on the leather gloves that Charley has given her, and sets to ripping out the vines that overrun the property. Mary Miller finally consents to come up on the cars once or twice to watch the proceedings—one of the boys produces a camp chair for her—though she grouses that she has no idea why they want to live all the way out here in the country. The shared labor establishes a fine camaraderie, and Charley watches as Emma laughs along with the others at the jokes and hijinks, and even joins in occasionally. When his little brother Billy shows off by balancing at the top of a huge brush pile, but slips and tumbles all the way down until he lands on his feet and cries out, “Ta dah!” as though he planned the whole thing, she laughs until tears roll down her sun-reddened cheeks.

Wagons pulled by massive draft horses trundle up to the lot to haul away the heaps of refuse, but it doesn’t take long to open up the property enough to see it clearly. It is everything that Charley has hoped for: a few mature trees to keep the house and yard from baking in the sun, but good exposure for the garden plots, which he is already designing in his head. Most of the property is flat, but it slopes gently away from the spot where the house is to be sited; that will keep rainwater from seeping into the cellar.

It is that cellar that causes Charley some worry, since it has to be hand-dug; he needs the weather to be dry enough to keep the hole from becoming a mud pit, but not so dry as to become sun-cooked and impervious to shovels. George’s crew is going to help, and Charley moves his week’s vacation to coincide with their availability. If there’s been a parade of vehicles to haul away the brush, then there is an entire battalion needed to remove the dirt that comes out of that cellar—and that’s even after Charley and his pals nearly destroy themselves moving the rich black topsoil from the excavation site to the back of the property ahead of time. Below that is a rocky brown loam, followed by a thick layer of the heavy orange clay common throughout the region. At one point, even Charley despairs of ever being able to complete the excavation. Once they finally break through the clay, though, the digging goes significantly faster.

Finally, on a hot, muggy August day that drapes itself over everything like a wet wool blanket, Charley invites Emma to climb down the ladder into the ten-foot-deep rectangular hole that is now flat, smooth, and hard-packed. She navigates the ladder with some trepidation, but once on solid earth at the bottom, she breathes in the earthy smell and feels the delicious coolness of the space. Being here reminds her of a crisp autumn day amid damp leaves—more like the end of October than the middle of August. Charley tells her, “The cellar will always be the coolest place in the house in the hot weather, but also won’t be freezing in the winter. Being underground moderates the temperature.”

She touches the walls, fascinated by the distinct layers of sediment that make her think of a vast sliced petit four. “And next is...?”

“We’ll pour the floor and then start the brickwork. That will take some time, but after that things should go quickly.”

Quickly, of course, is a relative concept. The floor is poured and has time to cure, but then a long rainy stretch moves in that delays the masonry work into autumn. George and his men are putting up a commercial building downtown that competes with the Flint Street project. Nonetheless, George is determined to get the house under roof before the first snow. That way, his men are able to work inside when they have time over the winter.

cd

Joe and Charley are in McCreary’s after work, and Charley is closely narrating the saga of the roof installation, which is just finishing up. It is a week or so after Thanksgiving, which Charley spends with Emma, Mary, and the boarder, Mrs. Klingelhoffer. Joe, meanwhile, has the rare opportunity to go home to spend some time with his family and boyhood friends, and to sleep in his old bed, which he finds blessedly peaceful. Charley is a fine roommate, but snores to rattle the cotter pins. It is this thought that puts a comical but indelicate image into his head of a Mrs. Emma Beck sitting up in bed next to a gap-mouthed, unconscious Charley, her eyes aghast and her hands clapped over her ears. The image makes Joe snort beer out of his nose, which, while painful, strikes him as even funnier, so he ends up spewing beer out of his mouth also.

“What the hell...?” Charley demands as he mops himself off.

“Charley, you talk about that house all the time. When are you going to talk about a wedding?”

Charley cups his palm behind his ear, “What? What’s that you say? Oh, wait.” He makes a production of cocking his head to one side and hopping on one leg while he knocks on his other ear. “Oh, that’s got it. Yep, I think it’s draining out now.” He sits back on his stool. “Lummox.”

“Priss.”

“So tell me how the thought of a wedding makes you spew beer all over me.”

“I’m just wondering who gets to warn your Emma that she’ll never have another minute’s sleep once she finds she’s stuck with you and your snoring.”

“I don’t snore.”

“You snore like a tornado kicks up wind.”

“That’s not me; that’s the mouse in my pocket.” They both have a good laugh at this, knowing it is Charley’s standing excuse for any socially unacceptable noises he makes. “And at least he doesn’t spit his beer all over me.” It’s Charley’s turn to be tickled by the image in his head and Joe has to wait for him to stop chortling to himself.

“So it’s the mouse in your pocket that’s keeping you from getting married?”

Charley takes a drink and considers the inside of his glass seriously. “It’s a hard thing, Joe. I’m trying to do the calculations in my head of when I think the house will be done. I need to propose a date that overshoots the finishing, but not so much that feelings are hurt.”

Joe nods sagely at him. “I see. And are you factoring in distance and windage to figure how far to lead the target? Good Lord, man, you’re getting married, not hunting geese!” Joe rolls his eyes. “Calculations. What a piece of work.”

Charley fixes him with a look. “Imagine for a minute, against all possible odds, that some girl ever agrees to marry you.”

Joe does imagine for a moment—a girl with long golden curls, fetching blue eyes, a pert nose, and a light, tinkling laugh—and almost sighs out loud.

“Yes, well, you hold onto that picture, for all the good it will do you. Now, consider—you and she, freshly pronounced husband and wife, arm in arm, gazing stupidly at each other—how far you would go to avoid moving in with your in-laws.” Joe’s image of his twinkling angel shatters in front of him at the horror of such an idea. He even turns a little pale. “Right. So now you’re not above running a few calculations of your own, are you? Windage! If only it was that easy!”

Joe’s beautiful vision now wrecked beyond repair, he gestures to the bartender. “I need another beer.”

cd

“We thank you, Lord, for the food upon this table and for the family who is gathered here in your name. Amen.” As Mary Miller finishes saying grace, she, Charley, and Emma make the sign of the cross before they pick up silverware. Mrs. Klingelhoffer is already eating. She is a Lutheran, and the prayer is not hers. She doesn’t typically participate during meals anyway; the others have learned simply to talk over or around her.

When Charley follows Emma into the house this afternoon, Mary looks at him shaking out his coat in the entry and remarks, “Anymore, I don’t need to look outside to know the weather, I just need to see Mr. Beck come through my door.” It is true that Charley has taken to staying for dinner only when the weather makes it impractical to go out and work the new property. But she and Charley have developed an easy camaraderie, and Mary looks forward to the rainy days.

“Well, old Grim stepped in it today,” Charley starts, in between bites of pot roast. Mary makes his favorite dishes when the weather foretells his visits, and the meals grease his storytelling machinery into a high hum. “He was supposed to order two gross of shearing collars, but he ordered twenty gross. The two would have lasted us most of next year as it is, but we figure that since he’s got no idea what a shearing collar is, he just thought he should get a bunch.” Another big bite of potato. “So here comes dolly after dolly of crates, and the delivery boys wanting to know where to put it all. Well, you should have heard old Grim howling. He’s got us all lined up, figuring on how to make one of us the goat.” Charley imitates Mr. Grimsley’s bug-eyed, open-mouthed rage, which makes them all laugh. “Then here comes Mr. Graves into the shop, standing with his fists balled up on his hips just a few feet behind Grim, and more crates just keep getting stacked around them. So here’s his face,” Charley demonstrates, “eyes all squinchy and his mouth in a tight white line, and he’s boring a hole into the back of Grim’s head. And all the while, Grim’s still snarling and snapping at us, just as clueless as a coonhound with a head cold.”

Replaying the scene in his head, Charley can no longer eat, and tears bead at the corner of his eyes, he’s laughing so hard. Emma and Mary lean in, anticipating the story’s climax. Even Mrs. Klingelhoffer blinks into engagement. “So here’s all of us, stuck standing there watching, and trying for all our lives to keep from dropping to the floor in hysterics. Smitty even let out a big old toot just from the back pressure.” Charley pauses to drink in some air and wipe his eyes. “Oh, but then! Here’s Mr. Graves: ‘Mis-ter Grims-ley!’” the four syllables spoken like individual words, and then,”—a sharp snap of Charley’s fingers—“instant silence. We’re standing there staring at each other, us and Grim, and you could almost see him shrivel up. ‘I will see you in my office. Now.’ Icy. To watch him slink after Mr. Graves, why we almost felt sorry for him.” The final carrot and a wink at Mary. “Almost.” He wipes his bread around the plate to get the last of the gravy. “Only took about a minute before those dollies were turned right around in mid-delivery to wheel those crates away.” The story over, Charley continues to chuckle to himself, toweling his fingers off, and pushing back a bit from the table.

Mary shakes her head as she rises to put the kettle on. Emma is up now also, clearing dishes and scraping plates. Mrs. Klingelhoffer drifts away from the table; they won’t see her again this evening. “Nothing that interesting ever happens in my office,” Emma says as she spoons tea into the pot and pours the boiling water in. “It’s all just gossip and speculation.” She sits the pot on a trivet in front of Charley and sees him grinning at her. Her face reddens as she glances down and smiles too. “Yes, I’ll admit that sometimes it’s appealing to listen in. Saturdays are always the most interesting.”

“Juicy,” Charley nods. “Friday nights get everyone in trouble.”

“That reminds me,” Mary says to Emma. “Make sure you have your bag packed on Friday. I’ll bring it with me on Saturday, and we’ll just leave from your office to go down to the station. We should easily make the one o’clock train.” She sees Charley looking at her quizzically. “Emma must have forgotten to mention that we’re going up to New York this weekend to visit Mary. We always try to fit in a visit between Thanksgiving and Christmas.”

It takes Charley just a second to realize she is referring to her other daughter. Emma pours tea for them as she says, “I forgot to tell you that I won’t be here to go to church on Sunday. But that doesn’t give you permission not to go. I just know you’ll use it as an excuse to spend the whole day on the house. Oh, and you said the roof is finished?” It’s not hard to grasp that there’s been a change of subject, so Charley leaves it alone until he’s saying goodnight, when he says to Mary, “What time should I be here Saturday morning?” At her raised eyebrow, he explains, “You need someone to carry your bags to the station.”

On Saturday, he’s at the door on Washington Street at the appointed time to pick up a valise in each hand and tuck a box under his arm. Mary walks beside him carrying a hatbox and another small bag. It’s an easy walk to the Post Office and from there to the B&P rail station on the Mall, but having the extra hands allows Mary to pack just a bit extra.

This is the first time they’ve ever truly been alone together, but there’s no sense of awkwardness.

“Emma explained to you about her sister?”

“Just that she’s in a home. Not why.”

Mary nods. “It’s hard for Emma, I know. She’s always been exceptionally fond of her father, and she was the apple of his eye.” She takes a breath, as though steeling herself for an impact. “When she was very young, Mary started having seizures. Not the falling-on-the-ground kind, just where she would go into a trance. She couldn’t help it of course, and we never knew when it was going to happen or how long it would last. But it enraged Christian. He thought she was malingering. He got it into his head that she was trying to make him look bad, as a doctor. He thought that he could…” She finds that she has trouble saying this out loud, and realizes it is the first time she ever has. “…that he could beat it out of her.” She has to make sure her voice is steady before she goes on, so she doesn’t terrify Charley with a threat of tears. “She had no idea why he beat her. To her, it just came out of nowhere, so she didn’t know what to do to avoid it. Imagine,” she says, almost to herself, “imagine one minute you’re eating supper and the next you’re being lashed with a horse whip.” She exhales in a long sad sigh. “After a time, she just retreated out of herself. She’s in New York because I needed someone who could do better with her than I could, and my cousin up there knew of the home. She’s done better over the years, to where sometimes we have a lovely visit. Other times, well, no. The damage was too much for time to heal.” They walk together in silence for a bit. “Anyway, I wanted you to know, in case.”

“In case of what?”

“In case it makes a difference.” This actually pulls Charley up short, and he can’t even think of words to say. “I didn’t imagine it would, but I just don’t want you to think we’re keeping secrets from you.”

Charley shakes his head as they start walking again. “Ma’am, if you want to get rid of me, you’re going to have to try a lot harder than that.”

They see Emma standing outside the post office at her normal exit, and she raises her hand to them. Charley lifts a valise toward her in return. In their last moment alone, Mary says, “Charles Joseph Beck, I say a prayer of thanks every night that you walked into our lives. I don’t want to imagine what it would be like if you walked back out again.”

cd

It is just after the turn of the year that Charley shares his plight with the one person who might actually be able to help him.

“You can see my dilemma, George. I need to make a firm offer so that her relatives or those busybodies at her office don’t jump to some damn fool conclusion that I’m not actually planning to marry her. I won’t have her held up to ridicule. But I’ve sure got no stomach for moving into her mother’s house, no matter whether it’s just a month or even a week. I’m glad to have her come in with us, once we’re settled, but not the other way. It would be a grim way to start out. Inauspicious.”

A sympathetic man, George can understand Charley’s position. He pulls out his annotated pocket calendar, held together with an elastic band and stuffed to overflowing with calling cards, jotted names and addresses, thumbnail sketches, and more. Not for the first time, he considers what it would mean to him if he ever had to replace this most irreplaceable object. On a scrap of paper, he does his own set of calculations, scribbling down the variables as he consults the calendar. He considers the ongoing jobs he has, the probability of others starting up, the size of his work crews, historical D.C. weather trends for winter and spring, and the list of primary items left to be done. He squints at the reckoning for a moment and makes a few significant noises. “July.”

Charley’s eyebrows shoot up in alarm. “July?”

“Yup. That allows a good buffer for any mishaps that might creep in. You can feel confident in a July date.”

“July,” Charley echoes faintly. May is so often a beautiful month in the area—tulips, azaleas, rhododendrons, tomato starts—though sometimes on the rainy side. June is typically drier and still cool enough, the most dependable of the spring months. But July? July can reliably be counted on to make the hellish descent into the insufferable heat and humidity of a Washington City summer, from which the area does not escape until well into September and sometimes not until October. “Early July?” he offers hopefully.

“Mid-July to be completely certain.”

If the house manages to be done in the spring, he can hardly ask Emma to wait until the fall for a wedding. And if George feels certain that July gets them a finished product, then it will be better for them to suffer through a city summer in their own home rather than in someone else’s. “July it is, then.”

After Mass that Sunday, Charley and Emma join the other parishioners bundled against the January chill and visit for a bit with friends outside the church. While Charley exchanges news with some of the men, Emma chats with Mrs. Schultz, who holds her little Marta, the Clark family with their flock of children, and Lillie Dietz, a friend of Emma’s from childhood. He watches her, noticing how different she seems now than when he first knew her. Her normal expression has softened and become more open, and she engages easily in the conversation. She laughs as two of the youngest Clark boys play hide and seek among the ladies’ skirts. Marta reaches out to her, and Emma takes her from Mrs. Schultz to have a private, happy exchange of the cooing that always passes between an adult and a baby. When he considers for a moment the flush that he suddenly feels, he discovers that he is proud of her.

As they walk together back to Washington Street, Charley says, “George feels certain that the house will be finished no later than July.”

She smiles, mostly to herself. “I suppose a year isn’t really a long time to build a house.”

He laughs. “No, not when you’re at the bottom of the list.” After a moment, he clears his throat. “So I thought, if you’re agreeable, that we might get married in July. Possibly mid-July?”

She looks at him and, after a pause, nods with a soft smile and squeezes his arm where her hand rests. They continue walking, each one smiling out to the sidewalk. As he delivers her to her doorstep, she turns fully to him. “Thank you, Charley. I...thank you.”

“Thank you, Emma. I know I’m a lucky man.” Without thinking whether or not he should, he takes her gloved hand and brings it up to press against his lips. He looks up to see a flush of pink in her cheeks, deeper than from the cold. She lets him hold her hand for another brief moment, then disappears into the house.

Charley stands on the porch for a minute, then hops down the stairs and dances a little jig out to the street. He’ll be heading out to the house just as soon as he changes clothes and grabs a bite, but at this moment his mind is elsewhere. He tips his hat back on his head as he strolls up the alley, hands shoved in his pockets, and whistles a wandering tune, a happy man.

cd

Though the space between January and July may seem expansive, there is much to do. Charley redoubles his efforts to move the project along, both inside and out, laying out the planting beds as early as February. As soon as the exterior walls are up, he basically moves into the shell, tying up his bedroll in the morning, coming back to the property after work, and falling back into his blankets well after dark. He keeps a minimal toilet set with him, going back to Mrs. G’s every couple days for a bath and proper shave, and changes of clothing. One evening after Charley leaves, having stayed only long enough to clean up and wolf down some dinner (“Delicious as always,” he says through a mouthful. “How can you possibly tell, eating like that?” “I just know,” he winks at her), Joe helps Mrs. G wash the supper dishes, since young Gretchen is still distributing the week’s clean linens and towels to the boarders. Joe works the hand pump and adds hot water from the kettle at her direction, and dries as she hands the dishes to him. Mrs. G gazes out into the darkness through the kitchen window. “It’s not going to be the same here when he’s gone for good and all.”

“Don’t I know it. I’m going to have to break in a roommate all over again!” He grins at her, but they each know the other is taking the loss equally hard. Joe consoles himself that he and Charley will still be a team at work, but he clearly sees that their days of sharing virtually everything in their lives is coming to an end. Who will he drink that after-work beer with now? And here’s Mrs. G, trying to smile at his lame joke. “Aww, Mrs. G, Charley said he’d come tend the garden for you still.”

“I know he did, Joe, and I know he means it. But he’ll be a married man. I think he’ll find very quickly that it will take every moment he has to get his own garden in order.”

Joe looks down at the dish he is drying, and says, “Well, he showed me a few things, Mrs. G. I’ll surely do my best with it.”

At the boyishness of it, Mrs. G’s breath catches in her throat and for a moment she fears she might weep. She flashes on an image of her own Heinrich—Henry in their daily lives—gone so long now, and wonders whether he would have turned out as fine as these two boys have. She hopes so. “Which will be perfectly wonderful, Joe, I’m certain of that,” she tells him as she puts a hand on his arm. He reddens but smiles at her. “Now get on with you, and go make up your bed!” She watches him leave the room, knowing that one day she’ll be watching him leave permanently, too.

cd

Initially, Emma plans to wear one of the dresses she already owns for the wedding; she has a navy one that’s nice, but it’s meant for fall and winter. Surprisingly, it is Mary who encourages her to splurge on a new outfit, and together they pick out a dove-gray cotton lawn for the wedding dress. They justify the expense by reasoning that she will wear it to church during the summers. Emma is not a seamstress, but her young cousin Lil does beautiful work, and quickly too. Lil brings the unfinished dress over to Washington Street one Saturday afternoon for the fitting, and helps Emma into it carefully, as much of it is still simply basted together. Lil stands behind and joins Emma in gazing at her reflection in the big mirror. “That’s a lovely color for you, Cousin Emma. I think it fits you well, don’t you?”

Emma continues to consider her mirror image. “I’ve never had as beautiful a dress as this in my life.”

Lil blushes at the compliment. “Are you excited? Are you nervous?”

“It’s all going to be so different. I don’t know that I’ve ever even been in a new house; I can’t imagine living in one.”

“I can’t wait to see it! I hear it’s wonderful.”

“Do you? Well, as it gets closer to being done, Charley wants me to see it less and less,” she laughs. “I think he wants to surprise me with it.”

“I think that’s sweet. What will Aunt Mary do now that you won’t be living here?’

“Oh, she’ll be moving in with us.”

“She will?”

“We planned for it when we laid out the house. It doesn’t make sense to pay rent here when we have so much space now. Plus we don’t want her living here by herself. So Charley will move her in the fall. That way, we’ll have some time to make the new house ready.”

Lil nods, appreciating the sense of it. “And time alone, too,” she suggests, then turns scarlet at having said it.

“But you should have seen Mother the first time we took her out to the property. To start with, it was the first time she’d been on the new electric car that goes out to Brightwood, and she wasn’t sure about that. Then, the longer we rode out, the wider her eyes got. By the time we were standing at the lot, she was sure we were insane.” Emma puts her hands on her hips in an imitation of Mary. “’Mr. Beck, I am a city girl! I never planned to take up farming, and I’m too old to start now!’ But you know Charley: he had her laughing over it in no time, and believing it was just this side of Paradise. I think she’s starting to get used to the idea.”

Lil laughs at Emma’s comical and accurate imitation of Mary expressing a strong opinion. She places the last two pins that temporarily hold the lace against the bodice and steps back. “Oh, Cousin Emma, you’re going to be a lovely bride.”

cd

As time draws closer, it’s obvious that there are sizeable jobs that won’t be finished by the wedding date: walls won’t be plastered in two of the four bedrooms, shutters won’t be hung, and paint will be missing from most of the outside of the house. None of that deters Charley. He presses both Mary and the busy seamstress Lil into procuring linens and making curtains; Mrs. G he doesn’t even have to ask. The women use their combined feminine touch to smooth the rough-hewn edges of the brand new house. In the last few weeks, they bring many of Emma’s things over so that they will be in place when she arrives as a new bride. Charley collects furniture from the house on Washington Street and from a storage barn his family still owns, far out in Bladensburg. The one thing he decides to purchase, his wedding gift to the two of them, is a new bed.

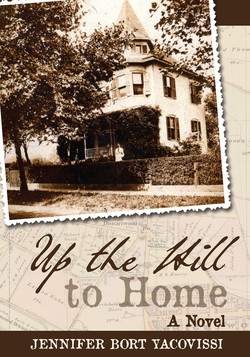

Finally, a bit less than a week before the ceremony, Charley and Emma ride out to the house. From the streetcar stop, they take the short walk to the intersection of Eighth and Flint Streets. Emma realizes that it has been almost two months since she’s been here, and she is stunned at the transformation. No wonder she’s seen so little of him lately. They stand outside the gate in front of the big house; as he promised, the gate is low enough to be welcoming, tall enough to definitively separate the yard from the street.

She can see that Charley is forcibly holding himself still, giving her a moment to take it all in: the wide front steps up to the porch, the offset front door that goes almost to the porch ceiling, the unadorned but still welcoming entrance. Finally she turns to him, which gives him permission to speak. “Do you want to see the inside or the outside first?”

“Let’s look at the outside.” She can feel her own excitement growing, and wants to savor the anticipation of the interior just a bit more.

Barely a breath interrupts Charley’s narration of the yard, which is more about the plans he has for it than about its current state. Most of the property is behind the house, and Charley has grand visions for it. There will be no summer vegetables this year, of course, but he’s still hoping to get some of the cool weather greens in before the season is completely over. Two of the beds are ready for planting. Here’s where the fruit trees will go, over there the nut trees. He has laid out some of the pathways through the yard with stones excavated while digging the cellar and the beds; one goes all the way out to the back alley, and another ends at the water pump above their well. Immediately next to the pump is the windmill. Together, George and Charley engineered this marvel and together explained the concept to Emma with great enthusiasm. She remains lukewarm to the idea, but has deferred to their expertise. This is the first time she’s seen the windmill, more than two stories tall on its spindly stork legs. Charley’s grin is so big as she looks it over that the ends of his mustache fan out over his cheeks.

“Does it work?”

“Wait and see,” is all he will say.

As they walk around the sides and the back, still unpainted, she admires the steps coming down from the kitchen, the storm cellar doors angled up from the ground to keep the water from seeping in and to make the entrance easier to navigate. There are big windows spaced evenly around the house. Having spent so many years in a row house in a back alley where the sun barely waves hello as it sails past, Emma longs for the luxury of sunlight in every room. Those windows are hers.

Finally, they arrive back at the point where they started the tour, and Emma stands to admire her favorite feature, which is primarily her own design: the turret, created by a set of three windows on each floor, angled in what looks like the first three sides of an octagon. On the first floor, the windows bump out onto the front porch from the parlor. Up from there, the bay is part of the main bedroom—theirs, of course—and beyond that is the attic. The turret ends in a tall cone of a roof that makes Emma think of a witch’s hat. She sees that someone has climbed all the way up there to cap the tower with a simple weather vane that points into the breeze.

They stand together at the bottom of the wide steps. For the first time, she notices the house numbers, black forged iron against a white, mitered board that hangs on a diagonal by the entrance: 741. They take their time walking up the steps to the front door, savoring the moment, and he ceremoniously hands her the key—more symbolic than useful it turns out, since it spends virtually all of its remaining existence hanging on a hook in the entry. She unlocks the door, and he opens it onto the hall.

With the exception of the turret, and the pantry and bath bump-out in the back, the house is almost completely square and built around a central chimney. Each of the four rooms on the first floor has a fireplace, though the main source of heat is a coal-fired furnace in the cellar. Starting from the entrance and moving counterclockwise are the hall, the parlor, the dining room, and the kitchen, with its small bump-out for the cooking pantry. Immediately across from the front door is the staircase to the second floor, with its four bedrooms, bath, and access to the attic. The attic itself has big dormers and the turret, a full-height ceiling and the same footprint as the story below—an open, airy, light-filled space. In contrast, the cellar is thoroughly utilitarian and subterranean, squat and unattractive but vital to the operation of the household.

Even with the many trips that Charley and his friends have undertaken to collect, deliver, and arrange furniture, the big house is still sparsely furnished, but she can see the care they have taken to make it welcoming. The effort that her mother and the redoubtable Mrs. G have put into sprucing things up is not lost on her either. A lovely bouquet of gladiolus greets her from a small table in the hall, and there are lace curtains at the front windows. She walks slowly through the rooms, admiring the familiar and unfamiliar items. The parlor is bare, with the exception of a large gilt mirror above the mantle and an older velveteen sofa, still nice, both from the Beck’s storage.

The dining room has but a small table and four unmatched chairs; however, Mary’s Schlegel family’s buffet and china closet are here, having survived every move of the Miller household since before Emma can remember. Mary’s furniture has begun to populate the house in advance of her permanent arrival.

They reach the kitchen, and Emma takes her time walking around the room, letting her fingers trail over each surface. Charley has succeeded in finding an icebox that is secondhand but lightly used and good quality. The woodstove sits in the pantry, which is lined with shelves, cabinets, drawers, and a countertop. Finally, Emma stands at the enamel sink, looking at the handles and faucets for hot and cold water; this is where the windmill comes in. As Charley explains it to her during the design phase, the windmill pulls water up from the well and pushes it all the way up to a tank that sits on the roof; the head pressure that gravity creates guarantees a good flow of water from any faucet. It’s all a new concept for her, having grown up thinking that a hand pump at the sink is the ultimate luxury. When he and George describe it to her, she rubs her forehead. “What if the wind doesn’t blow?”

“I can hand-crank the screw for the windmill to pump it up by hand.”

She shakes her head. “I still don’t understand about the hot water. If it’s not heated on the stove, where does it come from?”

George sketches out a picture for her, as he likes to do whenever he explains a concept. The water heater sits in the cellar and has its own scuttle for coal; the plumbers’ name for it, bucket-a-day, comes from the fact that the heater typically consumes a bucket of coal each day to keep the water hot. A large coil containing the water wraps around the heated core; water from the rooftop tank is piped into the bottom, and hot water pushes out from the top. “So when you turn on the hot side of the faucet, out it comes!” he concludes with a flourish.

To ensure a successful demonstration for Emma, George had stopped by earlier in the day to light the heater. Now she and Charley stand together at the sink, but she hesitates. He takes her hand and puts it gently onto the right porcelain faucet handle. “This is the cold. Just turn it this way to get the flow you want.”

With his hand still on top of hers, she slowly turns the handle. Water streams out, and pours more forcefully as she continues to turn. He holds his hand under the stream for a minute, and she copies his motion. In the heat of the summer, with the tank on the roof, the water will almost never be cold, as it is when it comes straight from the well. She turns the pressure up and down, fascinated by the expanding and constricting flow.

“Now on the hot side you need to be careful because it comes out hot enough to burn you.” He puts the stopper in the sink and lets Emma turn on the second faucet. Both are running into the sink now, and she can see the steam rising from the left side. Her mouth is agape. Charley swirls the water in the sink to test the temperature. “See what you think.”

Again she copies him to try out the temperature of the water. It is decidedly warm to the touch. Then she turns the cold water off and lets the steaming water pour in.

“Just be careful,” Charley cautions, and it is a brief moment before Emma pulls her hand back to keep it from scalding.

She laughs out loud. “Well, isn’t that just something! Everyone will want to try it!” She continues to look at the steam curling up from the water pouring out from the faucet, her faucet. It is not to be believed.

Charley finally turns it off, smiling at her obvious delight. “Let’s just take a peek upstairs, shall we?” They walk back into the hall, completing the circle, then up the stairs to the first landing. There, a tiny table holds another vase, this time with yellow rose blossoms that Charley grows in Mrs. G’s garden. They turn up the second set of stairs and end at the top landing, where the railing opens a view to the floor below. First, Charley shows her the finished bedroom that is to be Mary’s, which faces out onto the side yard to the west. Then the plumbed bath at the end of the hall that holds a sink, a huge claw-footed tub, and a flush toilet; they try each fixture in turn, to Emma’s continued delight. There is not much to see in the two unfinished bedrooms on either side of the main bedroom but, finally, he opens the door to their bedroom. He has arranged her things around the room: photographs, keepsakes, ceramic figurines, items that have been tucked away in her hope chest for many years. New curtains hang in the four windows that will allow the cross ventilation that might make summer nights almost tolerable. Finally, she looks at the bed, his wedding gift to her, knowing that he sees her redden slightly. The pillows and linens are new to her, freshly laundered and ironed, with a coverlet that touches the floor on three sides. The bed itself has a high headboard of dark wood and a central finial. At the foot of the bed, under a quilt, is that same hope chest, which for so long held no hope at all. And to have ever imagined this—all of this, any of this—well, she could never have stuffed it all into that chest and had room to close the lid. She slides her hand under his arm, but can’t look at him. Just as when he proposes, she simply says, “Thank you, Charley.”

cd

As their present to Charley and Emma, and to stave off the sadness of the impending separation, Joe and Mrs. G decide to throw a party for the bride and groom. Three days before the wedding, they, Gretchen, and the rest of the boys scrub the common areas, string lanterns in the back, set up tables, and put the small beer on ice. Mrs. G outdoes herself in the preparation of the food, helped in the endeavor by her new great friend Mary Miller. Emma invites some folks from church, family who are going to be at the wedding, and some old friends. Several of Charley’s siblings and buddies from work join the fellows from Mrs. G’s to round out the party. It’s not long before someone starts a sizeable fire in the fire pit, and a little band forms with an accordion, a Jew’s harp, two harmonicas, and a few sets of spoons. Soon after that the dancing starts. Charley, of course, is the first one out, dancing a bit of a jig and then—after Emma laughs and shakes her head “no” at his wordless invitation, but continues to clap in time with the music—grabbing up Mrs. G to start a reel as the other dancers join in.

Later, within the general gaiety of the party, Charley notices his roommate staring ardently across the yard; Charley follows the direction of his gaze and at the other end of it discovers Cousin Lil, who is blushing prettily and keeping her eyes on the ground, except for when she feels emboldened enough to glance in Joe’s direction. From a distance, Charley catches Emma’s eye and nods first toward Joe and then to Lil. Emma sees what he means immediately, and walks over to Joe while Charley strolls to Lil and stands beside her. “Are you enjoying yourself, my dear?”

Lil is startled from her surreptitious flirtation, and her color goes from pink to deep red as she is caught out. “Oh, very much so, Cousin Charley. It’s a wonderful party.”

“Well, look who we have here,” he says in false surprise as Emma approaches with Joe beside her. Charley makes the introductions between the two, neither of whom is capable of coherent speech or even, with the distance closed, of making eye contact. “Emma and I are going to get a glass of lemonade, if you’ll excuse us.” Over at the refreshments table, Emma sips lemonade as she and Charley watch the unfolding scene with conspiratorial delight. Joe and Lil have found their tongues again, though both still appear to be fascinated by the ground between them. Joe glances over at Charley and Emma long enough to offer a look of pure thanksgiving, and Charley winks at him. She isn’t blonde, and her nose is rather more round than pert, but Lil is lovely nonetheless and, indeed, has a light, tinkling laugh.

Charley takes in the music, the light from the fire and the lanterns, the yard filled with his friends and future relatives, and thinks he might burst. Instead, he slips his arm around Emma’s waist, boldly proprietary, and squeezes. She leans in against his shoulder and he feels rather than hears her sigh. Heaven.

cd

The wedding itself is a small, mid-week affair. It is a rare day in July of low humidity and a fresh breeze. Emma, resplendent in her lovely new dress, carries a nosegay of white rose buds and purple violets. Charley is in his suit, cleaned and pressed for the occasion, his mustache freshly trimmed and his hair damp combed. Joe, of course, stands for Charley, and Lillie Dietz, her childhood friend, for Emma. Among those on the bride’s side are Mary’s sister Katie Schlegel, down from Baltimore, and Katie’s freshly smitten daughter Cousin Lil. On Charley’s side are several of his many siblings: his older sister Margaret and brother Jacob; younger brothers Harry, Louis, and Billy; and Lizzie, the baby of the family.

Father Mendelsohn celebrates the brief ceremony. When he asks, “Who gives this woman in marriage?” it is Mary who answers, since there are no male relatives to stand in for the late Dr. Miller. No one in attendance offers any reason why the two should not be joined in holy matrimony. When Father Mendelsohn at last gives his permission, Mr. Charles Joseph Beck, age twenty-six until September, turns to the newly minted Mrs. Emma Lucretia Miller Beck, thirty-seven the previous February, and, for the first time, kisses her.