Читать книгу Warbird - Jennifer Maruno - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

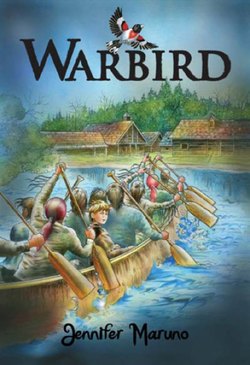

FIVE Arrival

ОглавлениеThe setting sun gave the weathered stakes of the palisade wall a glow of burnished silver. As the canoe moved along the river, bark shingle roofs came into view. A soldier watching from the parapet waved in their direction.

Médard and Pierre paddled down the small waterway into the very heart of the mission. The big canoes would never have fit, Etienne thought.

Two men and a priest hoisted the wooden bridge that lay across the canal. Etienne looked around at the squat square buildings of hand-hewn logs. Heavy wooden shutters framed windows curtained with oiled deerskins. Big chimneys of mud and stone spewed smoke. A man and boy at a saw trestle slowed their work and tipped their caps. The boy who had a wind-whipped face and tight curly hair grinned and waved. The smell of sweetgrass filled the air as they stepped onto the platform of logs.

“Welcome. I will take the chickens for you,” a man in threadbare garb of black offered. “I am Father Bressani.”

Etienne blinked at the ragged scar across the man’s face. “They are for Father Rageuneau,” he said, moving the chickens closer to his side.

“Father Rageuneau will not expect to see anyone until you have given thanks for a safe journey,” the Jesuit said. He turned to the man approaching. “Brother Douart will show you the way to the chapel.”

The lay brother’s long, dark hair hung in strings about dark, hollow eyes. His thick, greasy moustache needed a trim. With a toss of his muddy cape, Douart led the group of travellers towards the cluster of log buildings.

The two sides of the fort facing the forest were masonry, flanked by bastions. “Miller, blacksmith and carpenter,” Douart said, naming each building they passed. He pointed to the narrow two-storey barn across the way. “Your bed,” he said to Etienne, “is above the stables.”

Douart led them to the threshold of a small square building which served as a chapel. “When you are finished,” he told them, with a backward glance, “you will be fed.”

Etienne put the chickens down next to the chapel door and followed Médard and Pierre into an earthy interior with white clay walls that smelled of warm wax. A single candle flickered at the altar, where they bowed their heads and gave thanks. Etienne turned to go, but on second thought bowed his head again. His mother deserved a special prayer. She would be the one to bear the brunt of his father’s anger at his disappearance. Etienne also prayed that the orphan would stay to help his father.

His two companions led Etienne into the great hall. Eating and drinking men filled the log benches around the rough pine tables. Some looked up when Etienne paused in the doorway. Holding the chicken cage in the air, he yelled out, “I have a gift for the Father Superior.”

Murmurs and laughter came from the crowd.

A full-bearded priest rose from his meal. His long-sleeved black garment covered his body from neck to feet. Around his collar of plain white he wore a chain of blue porcelain beads, ending in an iron cross. “I am the Father Superior,” he said. Beckoning, the priest called, “Show me what you have brought.”

Etienne carried the cage through the amused crowd. He placed it on the table in front of Father Rageuneau. “This is Francine and her husband Samuel,” he said. “They have travelled far, just like Champlain himself.”

The Jesuit leaned down. “Like Champlain, you say,” he said, looking at the two scruffy black hens. “Thank you, we will be happy to have their eggs.”

“I will take them,” Douart, the scruffy lay brother said, placing his hand on the battered cage.

“You can’t just throw them in the coop,” Etienne protested. “They have to be put on a roost at night. Then when they wake, they’ll think they’ve always lived there.”

“Monsieur Le Coq,” one of the men at the next table asked in a loud voice, “is it true?”

“It didn’t happen to me,” a voice replied, and a roar of laughter followed.

“What is it that you have come to do, my son,” the Father Superior asked kindly.

“Explore and hunt,” Etienne answered enthusiastically.

“You probably will,” the Father Superior said, “but how will you serve God?”

Etienne thought of the chores he’d left behind. “I know how to raise chickens and tend a garden,” he said. Then he remembered a phrase he’d heard his father say often and repeated it. “I come from a long line of farmers.”

“And what long line might that be?” Father Rageuneau asked.

Etienne stared at the priest blankly. He could not remember the boy’s last name.

“Your family name,” the man seated beside Father Rageuneau prompted. “We want to know your father’s family name.”

Etienne stared at the ruddy-skinned man with black hair and brown eyes. “Hébert,” he blurted suddenly, taking the name of the family at the next farm. “All the men of the Hébert family are farmers.”

“Surely you are not a descendant of the great Louis Hébert,” the black-haired man said, putting down his spoon. “Why, he was much more than a farmer. He was a famous apothecary.”

Etienne had not heard of this particular Hébert, but he guessed by the glint in this man’s eyes, it would be a good heritage to have.

“You must mean my Uncle Louis,” he said, nodding. “My mother speaks of him often.”

“But,” Father Bressani said, “Father Lejeune wrote you were an orphan.”

Etienne lowered his head, studying the black leather boots before him. “I meant my father and mother used to speak of him often,” he said in a whisper.

“He will work with me,” the man beside Father Rageuneau stated. He reached across the table and shook Etienne’s shoulder. “You can help out in the apothecary.”

“Good,” said Father Ragueuneau. He leaned into Etienne and whispered, “But I must warn you, Master Gendron is very particular about work done around the hospital.”

“What about the chickens?” Etienne asked, giving Francine and Samuel a tender look.

The Father Superior smiled. “You can tend to your chickens as well,” he said.

“You can sleep with them if you like,” Douart added, returning to his meal.

Etienne sat down to eat. The meal, nothing more than rabbit stew, tasted delicious.

After dinner, he carried his chickens with pride to the long, low building beside the palisade. “Tonight we sleep apart,” he told them as he put them on a roost. “There will be no more canoes, no more rapids and no more fires.”