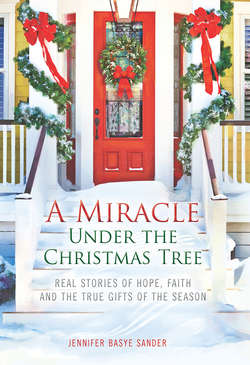

Читать книгу A Miracle Under the Christmas Tree - Jennifer Sander Basye - Страница 10

FINDING JOY IN THE WORLD ELAINE AMBROSE

ОглавлениеDecember 1980 arrived in a gray cloud of disappointment as I became the involuntary star in my own soap opera, a hapless heroine who faced the camera at the end of each day and asked, “Why?” as the scene faded to black. Short of being tied to a rail-road track in the path of an oncoming train, I found myself in an equally dire situation, wondering how my life turned into such a calamity of sorry events. I was unemployed and had a two-year-old daughter, a six-week-old son, an unemployed husband who left the state looking for work and a broken furnace with no money to fix it. To compound the issues, I lived in the same small Idaho town as my wealthy parents, and they refused to help. This scenario was more like The Grapes of Wrath than The Sound of Music.

After getting the children to bed, I would sit alone in my rocking chair and wonder what went wrong. I thought I had followed the correct path by getting a college degree before marriage and then working four years before having children. My plan was to stay home with two children for five years and then return to a satisfying, lucrative career. But, no, suddenly I was poor and didn’t have money to feed the kids or buy them Christmas presents. I didn’t even have enough money for a cheap bottle of wine. At least I was breast-feeding the baby, so that cut down on grocery bills. And my daughter thought macaroni and cheese was what everyone had every night for dinner. Sometimes I would add a wiggly gelatin concoction, and she would squeal with delight. Toddlers don’t know or care if Mommy earned Phi Beta Kappa scholastic honors in college. They just want to squish Jell-O through their teeth.

The course of events that led to that December unfolded like a fateful temptation. I was twenty-six years old in 1978 and energetically working as an assistant director for the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. My husband had a professional job in an advertising agency, and we owned a modest but new home. After our daughter was born, we decided to move to my hometown of Wendell, Idaho, population 1,200, to help my father with his businesses. He owned about thirty thousand acres of land, one thousand head of cattle and more than fifty 18-wheel diesel trucks. He had earned his vast fortune on his own, and his philosophy of life was to work hard and die, a goal he achieved at the young age of sixty.

In hindsight, by moving back home, I was probably trying to establish the warm relationship with my father that I had always wanted. I should have known better. My father was not into relationships, and even though he was incredibly successful in business, life at home was painfully cold. His home, inspired by the designs of Frank Lloyd Wright, was his castle. The semi-circular structure was built of rock and cement and perched on a hill overlooking rolling acres of crops. My father controlled the furnishings and artwork. Just inside the front door hung a huge metal shield adorned with sharp swords. An Indian buckskin shield and arrows were on another wall. In the corner, a fierce wooden warrior held a long spear, ever ready to strike. A metal breastplate hung over the fireplace, and four wooden, naked aborigine busts perched on the stereo cabinet. The floors were polished cement, and the bathrooms had purple toilets. I grew up thinking this decor was normal.

I remember the first time I entered my friend’s home and gasped out loud at the sight of matching furniture, floral wallpaper, delicate vases full of fresh flowers and walls plastered with family photographs, pastoral scenes and framed Norman Rockwell prints. On the rare occasions that I was allowed to sleep over at a friend’s house, I couldn’t believe that the family woke up calmly and gathered together to have a pleasant breakfast. At my childhood home, my father would put on John Philip Sousa march records at 6:00 a.m., turn up the volume and go up and down the hallway knocking on our bedroom doors calling, “Hustle. Hustle. Get up! Time is money!” Then my brothers and I would hurry out of bed, pull on work clothes and get outside to do our assigned farm chores. As I moved sprinkler pipe or hoed beets or pulled weeds in the potato fields, I often reflected on my friends who were gathered at their breakfast tables, smiling over plates of pancakes and bacon. I knew at a young age that my home life was not normal.

After moving back to the village of Wendell, life went from an adventure to tolerable and then tumbled into a scene out of On the Waterfront. As I watched my career hopes fade away under the stressful burden of survival, I often thought of my single, childless friends who were blazing trails and breaking glass ceilings as women earned better professional jobs. Adopting my favorite Marlon Brando accent, I would raise my fists and declare, “I coulda been a contender! I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am.”

There were momentary lapses in sanity when I wondered if I should have been more like my mother. I grew up watching her dutifully scurry around as she desperately tried to serve and obey. My father demanded a hot dinner on the table every night, even though the time he would come home could vary by as much as three hours. My mother would add milk to the gravy, cover the meat with tin foil (which she later washed and reused) and admonish her children to be patient. “Your father works so hard,” she would say. “We will wait for him.” I opted not to emulate most of her habits. She fit the role of her time, and I still admire her goodness.

My husband worked for my father, and we lived out in the country in one of my father’s houses. One afternoon in August of 1980, they got into a verbal fight, and my dad fired my husband. I was pregnant with our second child. We were instructed to move, so we found a tiny house in town, and then my husband left to look for work because jobs weren’t all that plentiful in Wendell. Our son was born in October, weighing in at a healthy eleven pounds. The next month, we scraped together enough money to buy a turkey breast for Thanksgiving. By December, our meager savings were gone, and we had no income.

I was determined to celebrate Christmas. We found a scraggly tree and decorated it with handmade ornaments. My daughter and I made cookies and sang songs. I copied photographs of the kids in their pajamas and made calendars as gifts. This was before personal computers, so I drew the calendar pages, stapled them to cardboard covered with fabric and glued red rickrack around the edges. It was all I had to give to those on my short gift list.

Just as my personal soap opera was about to be renewed for another season, my life started to change. One afternoon, about a week before Christmas, I received a call from one of my father’s employees. He was “in the neighborhood” and heard that my furnace was broken. He fixed it for free and wished me a merry Christmas. I handed him a calendar, and he pretended to be overjoyed. The next day, the mother of a childhood friend arrived at my door with two of her chickens, plucked and packaged. She said they had extras to give away. Again, I humbly handed her a calendar. More little miracles occurred. A friend brought a box of baby clothes that her boy had outgrown and teased me about my infant son wearing his sister’s hand-me-down, pink pajamas. Then, another friend of my mother’s arrived with wrapped toys to put under the tree. The doorbell continued to ring, and I received casseroles, offers to babysit, more presents and a bouquet of fresh flowers. I ran out of calendars to give in return.