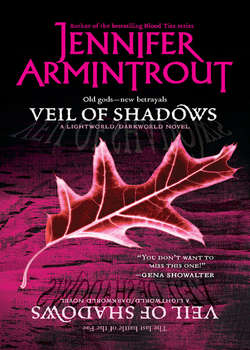

Читать книгу Veil Of Shadows - Jennifer Armintrout, Jennifer Armintrout - Страница 8

One

Оглавление“You were lucky beneath Boston,” the old ferry captain, Edward, said. “You know what happened to them down in New York? Flooded ’em out. Drowned ’em. Them creatures that didn’t drown, them were hunted by the Enforcers and killed.”

Cerridwen opened her eyes, reluctant to leave the sleep that had been her refuge from the terrible sickness she’d felt while awake. The vessel they had departed on that morning, a ramshackle boat the man had kept calling a ferry—not, Cedric had assured her, in mean-spirited jest toward their kind—still churned and tossed. How the Human could stand, so straight and balanced, as the craft pitched from the crest of one wave to another, Cerridwen did not know. But the motion made her stomach seize, her head go dizzy.

Cedric and the rest of the Fae they traveled with seemed unaffected by the motion, as well. Cedric, particularly, seemed to revel in their time on the sea, standing at the prow, listening to the bearded old man call out stories against the wind and the spray. Though the blinding sun had set, Cedric still stood in the place he’d inhabited when she’d fallen asleep. Face turned toward the horizon, an expression of serene pleasure—or as much of one as Cerridwen had ever seen on the ancient Court Advisor. Calmness gilding his features the way the morning sun had, it seemed as though he had completely forgotten the precarious position of their future, and the violence they had left behind.

Cedric had been alive long before the rending of the Veil had spilled all the creatures of the Astral onto Earth. To him, the sun, the wind, the water were all old friends. They greeted him with familiarity and Cerridwen realized how much he must have longed to escape the cramped and dank Underworld. To her, born after the Fall and in the cavernous Underground, the elements showed only hostility.

Cedric nodded, but did not face the old man. “I did not know there were other cities…I thought that most had died in the battles, and that whoever remained of us were underground in the same area. That it was just too large—”

“If you’d kept going, you’d hit the end.” Edward spoke with such authority, it was as though he’d been there.

It was not impossible to believe. Cerridwen had always wondered that the boundary between the Lightworld and the Darkworld was so well defined, and yet no one seemed to know if there were other boundaries, and if there were, where they lay.

“Everyplace where they didn’t just get rid of you. New York, that was one of them. Boston, well…you saw what that’s become. No one wanted to stay, once your kind were underground. Up and left. Most of the cities went that way. Decided it was easier to give up and leave than try to live with knowing what existed just beneath them.” The old captain seemed to be amused by this.

It was not amusing. The Humans had forced them underground, then abandoned the very spaces they’d coveted for themselves. Cerridwen wondered if she’d ever understand these strange beings.

She sat up, her stomach lurching. But before she could speak, Cedric turned, the serenity bleeding from his expression. “You are awake.”

She wished he would not look at her with such concern. Concern she did not merit. “As you can see.”

“You should rest. The mortal healing has only restored your body. The sickness you have felt—”

“Seasickness, the Human says.” She closed her eyes. It only made the sensation worse. “Is this because I am part Human? The element does not affect you.”

“It is not because of your Humanity. It is because you have never been outside the Underground.” He held out his hand for her, and when she did not move to take it, he stooped and lifted her, blanket and all.

“Put me down!” She had enough strength, despite her sickness, despite the wound in her ankle, to be outraged.

He did not listen, and she had not expected him to. He set her down gently in the place where he’d been standing before, let her lean on him for support. “Look out there, at the horizon. The place where the sky meets the water.”

“I know what a horizon is,” she snapped, pushing down the finger he used to point the way.

“That won’t help,” Edward called to them cheerfully. “Not a fixed object.”

“It will help,” Cedric reassured her. “We see things differently than they do.”

She squinted against the sun. Its light did not assault her the way it had when they’d first emerged from the Underground, but she had to blink against it to make out the difference between the dark of the water and the blinding curtain of sky.

“You are resisting the elements, because you are unfamiliar with them. You fight against them,” Cedric told her, and again he pointed out to the horizon. “They do not fight against each other. See how when the waves rise, the sky relents? You must learn to do the same.”

It did make her feel a bit better. Though the craft still rocked against the waves, she did not struggle against the movement in an attempt to keep herself upright. Instead, she let the motion rock her, and she did not stumble or fall.

“Getting your sea legs,” the old Human said. “You’ll need ’em—you got a long way to go still.”

“I thought we would meet up with Bauchan by nightfall.” Cerridwen did not look away from the waves, or lean away from the comforting presence of Cedric standing behind her.

“We will,” Cedric began. “But we will meet up with the ship that the rest of the Court is already on, and then we will sail across the sea. The False Queene’s Court is on an island, what you might think of as the Land of the Gods, if your mother taught you about it.” His tone suggested that he did not believe Ayla had instructed her daughter correctly in this matter, and he continued. “It was less difficult for us to travel when we lived on the Astral Plane. We merely spoke the words, or imagined the scene, and we could be anywhere.”

“Not so much anymore, huh?” Edward called down. “Don’t you worry, though. The captain of the Holyrood will get you where you’re going, if not as quick as you’re used to.”

Cerridwen grew annoyed at the weathered Human’s constant interruptions, and limped back to her pallet in the shade. She crouched and flared her wings for balance, resting her weight on the front of her feet. Something about this posture made Cedric look away, but she did not know what could bother him so. Probably, he still hated her for her stupidity. It was his right. She had foolishly betrayed her mother, her entire race, and gotten so many killed in the process. Both her parents, though she had not known it at the time, and countless guards and Guild members. If Cedric wished to hate her for all time, well, she would not argue with him.

But he had saved her, had he not? Not just from the Elves, but from the Waterhorses in the Darkworld, and again in Sanctuary. When she’d been willing to stay and die beside her mother, he’d dragged her into the Upworld. When she’d been too weak to continue, still he’d carried her, despite his own fatigue. Perhaps he did not hate her. He was angry with her, that much was certain. He had made a promise to protect her, but if he truly hated her, would he keep that promise?

She was too weary to think of this now. There would be a confrontation with Bauchan when they reached the ship called the Holyrood, that was certain. At the very least, he’d question her right to kill her mother’s treacherous Councilmember, Flidais, who had been working with him. In the end, no matter her reasoning, he would be upset over Flidais’s death and would not accept her as Queene, being eager to steal away her inherited Court for his own False Queene.

A thought struck her, one she did not like. “Cedric, if there are others…other Undergrounds, like ours, could there not be other Queenes and Kings? Who believed that they deserve to rule over all the Fae?”

“I had thought of that.” Cedric sat down, his legs folded beneath him. His wings, papery thin and colored like those of a moth, shivered on his back, sending motes of blue powder through the beams of sunlight that reached beneath the ferry’s upper deck. “It is heartening to think that there are more of us. That might prove useful, especially if we can garner their sympathy in our plight. But there is no guarantee that we will be able to contact them, or that they will look kindly on rejoining Mabb’s Court.”

Cerridwen eased her weight onto her uninjured foot. “Mabb was the Queene. The true and rightful Queene of the Fae from before our fall to Earth. All other Fae fought behind her in the war against the Humans, did they not?”

“She was. They did.” There was sadness in his eyes as he talked about her. Cerridwen, born after Mabb’s death, had never seen the Faery Queene who’d preceded her mother. The rumors of Cedric’s involvement with Mabb had persisted, though, and Cerridwen wondered if lost love was what made him seem so very troubled now.

“Mabb was not a popular ruler. Not once the Veil was torn asunder. Some blamed her, for allowing Humans to glimpse us as we were trooping, or for not punishing those in her Court who intentionally sought out the company of Humans.” He fell silent, looked out toward the water. “Ah, well. It is not the past that will help us now. You will meet Lord Bauchan tonight. Are you ready?”

She snorted. “You make it sound as though I am going to war.”

“You are, in a way.” Though he shrugged, his expression held a seriousness that Cerridwen did not like. “You are fighting for control of your Kingdom.”

Another derisive sound crawled up her throat, and she swallowed it. “Some Kingdom. My inherited subjects ran and left my mother when she needed them most. If they cared so little for her, why should they care about me?”

“By your same thinking, why should they care about Queene Danae enough to bend their knees to her?” He was right, and infuriatingly reasonable. Cerridwen said nothing. “Your mother would not have wanted you to give up. She did not wish to see her Kingdom in the hands of this False Queene. Perhaps…” he continued, then stopped himself.

She had seen him do this very same thing with her mother. Though he might have an idea, he would withhold it until invited, and would not speak out above his station to the Queene. Whether he did it out of habit or he held Cerridwen in the same respect that he’d had toward Ayla, she did not know. But it pleased her, nonetheless, to be treated as though she were worthy of deference. “Perhaps what?”

“Perhaps, when we see Lord Bauchan, I should speak on your behalf.”

That destroyed the illusion. He thought she was incapable of speaking for herself without some disastrous outcome. A part of her agreed with him, was thankful, even, that she would not have to pretend at courtly manners and political thinking. She had no head for either of them, and even if she had, her hatred of Ambassador Bauchan, the fiend who had come to the Lightworld with the intent of causing civil war, would have broken her concentration.

“Yes, fine.” She nodded, a bit too enthusiastically. “It would help keep up the pretense that you are the Royal Consort.”

He nodded. “Yes, that is something that needs to be established early with Bauchan. I would not think that seducing the Royal Heir would be below him, if it would give him what he needed to succeed at his own Court.”

“No longer the Heir—the Queene,” she corrected, though even in her insistence the title was too new to be comfortable for her. “Perhaps we should do with Bauchan as we did with Flidais. After all, is he not guilty of the same offenses she is?”

“He is not,” Cedric stated firmly. “Bauchan came to your mother’s Court with no deception that we could not see, and in spite of the fact that your inheritance comes from Mabb’s succession, he was not considered your subject when he arrived, and this Queene Danae is unlikely to accept your killing him. Flidais hid her plans, and turned traitor to her own Queene, in contrast. Besides, we need Bauchan. He is our only guide to finding Danae’s Court and some measure of safety.”

Silence fell between them again, the only sound the mechanical chug of the ferry’s engine and the soft slap of the waves against the tiny craft. The sound had lulled her to sleep that morning, and, in hearing it again, woke the vestiges of those things she’d seen in her fitful slumber. Without knowing why she did so, she suddenly blurted, “I had a dream, earlier. While I slept from my sickness.”

Cedric made a noise of uncommitted interest. “Do you believe it means something?”

Did she? It was such a simple dream, and she had never truly believed in such nocturnal signs. “I do not know,” she answered honestly. “If it does mean anything at all, I would not know how to interpret it. And I have never given much credit to dreams.”

“If you tell me what it was about, I might be able to help you.” He looked out to the water again. “Or, if you prefer to keep it secret, I will understand.”

“There is no secret to keep. It was not disturbing, or terribly important.” That was not entirely true. When she thought of the images, a feeling of grave urgency taunted her. “I saw a forest, as though I were standing in it, and I was alone. I came upon a clearing to see a white bull.” She closed her eyes, and in her mind saw the shaggy, matted coat of the animal as it stood, almost ghostly white, in the darkness. “In the sky above the treetops, the stars made out the form of three triangles, locked together in such a way as to make one large copy of themselves.” She stopped herself. “Can they do that? Stars, I mean? Do they show pictures?”

“They show forms that Humans can navigate by, forms that tell a story. But they cannot twist themselves into something they have not shown before.” He seemed troubled, but in a flash that troubled expression was gone. “Ah, well. It was probably just a dream. Nothing worth worrying over.”

And though she might have agreed with him before, the vision had crept back into her mind, insisting upon a place there. It would not have done that, if it did not have something to tell them. She did not know how she was so certain of this, but she was, and his studied disinterest irritated her.

“I am going to go watch the sea,” Cedric announced, as though it were not a dismissal. “You could come, if you wished. The ferryman is good company.”

“Human company,” she said, waving a hand. “If that is your idea of good company, then you may indulge all you please.”

His smile was tight, pasted on. “Yes, it will do you good to rest before we meet with Bauchan.”

Only after he strode from beneath the deck, his tread heavier on the floor than any immortal creature’s should be, did she realize how very much she’d sounded like her old self, the immature child who’d hastened her parents’ deaths through impatience and petulance.

The ferry arrived at the place where Bauchan’s ship was harbored just after nightfall, almost to the exact minute, that the ferryman had promised. At least, that was what he told them, and Cedric had no reason to doubt the Human.

Though Cedric had been sad to see the sun set—having no idea when he would get another opportunity to view its radiance and after all the years spent underground having become greedy for it—he recognized that it was for the best that they make this meeting under cover of darkness.

The ship was not moored at the docks but anchored at the mouth of the harbor—the farther away from Humans, the better, in Cedric’s opinion—and the ferryman blew his horn as they approached. Lights appeared at the rail of the ship’s deck, high, impossibly high above them, and as the little boat drifted sideways to meet the wall of red-painted steel, the ferryman silenced the engines and called out a friendly “Halloo!” to figures that Cedric could not see from his vantage point.

“What if they will not let us board?” Cerridwen fretted beside him. She stood, a blanket clutched tight around her shoulders as if ready to run, though there was no place to go.

The six guards who had accompanied them from the Palace, and who had been the last witnesses to the carnage wrought in the Underground, stood in their regal finery, toting the bundles that held all the wealth they were able to recover from the sacked Faery Palace. Cedric looked them over with some dismay. Though their clothes were that of courtiers, they held themselves in the stiff manner of soldiers still. Cedric only hoped that Bauchan would be dazzled by the velvet and silk, and not give a thought to the way the men seemed ready to throw themselves over the Royal Heir at the slightest sign of, well, anything, soldiers being more loyal than courtiers.

Cedric looked at Cerridwen now. She was, for all intents, the Queene. But she was hardly fit for the post, and hardly looked it. No matter how she’d carefully bathed and dressed, she could not hide the hollow look that sorrow had imprinted on her, nor the fatigue from her injury. He should say something to her now, to reassure her, but he could not. He did not know what would happen to them, should Bauchan refuse to bring them to Queene Danae’s Court. He did not expect such a refusal, but for the past two days its possibility had been much on his mind.

Instead of comforting her, he concentrated harder on making out the conversation between the ferryman and the Humans on the ship. For their part, he could hear very little, but every word that Edward spoke was exactly as Cedric had coached, but cushioned in the gentle, rolling tones the Human preferred, as though no word should be hurried from his lips, and nothing of import should pass that way, either.

“Just another load of special cargo,” he called out to the Humans high above their heads. “You’ll be wanting to drop the gangplank, so I can unload it.”

There was a pause, mumbling that was not clear.

“Oh, he’s expecting this delivery, all right,” Edward said easily. “Brought special by his importer, you know.”

More of a pause, more mumbling. Cedric’s antennae buzzed against his forehead, and he smoothed them back against his hair, willed himself to be calm.

Whatever they had asked him, Edward managed to sound very put off by it. “Well, go on and check with him, if you gotta. But I know what I gotta do, and that’s get back to the missus before sunup, or she’ll have my hide and I don’t want to think what else…. Get goin’, then, and give me a rope to tie up by.”

The Human’s words were met with a loud slap against the deck, the rope falling, if Cedric guessed correctly. Then, nothing. Silence, broken by the sound of the water trapped between the two vessels as it knocked from one hull to the next. Edward did not come down from his little wheelhouse, nor did he call out any encouragement to them.

“What is happening?” Cerridwen hissed, as if afraid to interrupt the gentle sounds of the night sea.

Cedric did not raise his voice much above a whisper, either. “He will not call down to us now. Sounds carry across open water, and if any Enforcers patrol the harbor, you would not want them to overhear exactly what cargo is being traded, would you?”

She shivered, sank farther into her blanket.

Something screeched, and Edward appeared below the deck, waved to them to come to the back of the boat. He doused the lights on the craft, all but the small green and red ones that shone over their heads to indicate their presence.

“He wants to ‘inspect the cargo,’” Edward said, rubbing a hand across his grizzled jaw. “I thought you said you knew these ones?”

“We do.” Cedric looked to the source of the screeching noise, saw through the darkness to where a door had opened at the side of the ship. “I did not say that we were on the best terms.”

“Best terms,” the old Human spat. “I don’t like the sounds of that, and I won’t lie and be telling you otherwise. We run a respectable operation, my wife and I, and I hope you’re not preying on our good nature.”

“Sir, I assure you, if we are not welcome here, we will not trouble you further.” Cedric did not know how he would make good on that promise, but he did not wish to think on it now. Right now, the most important matter was to convince Bauchan.

Humans called out orders as quietly as they could from the large boat, and Edward answered them in hushed tones, as well. The result of their combined efforts was the placement of a long walkway between the two vessels, which, under cover of darkness, a few Fae shapes made their way across the expanse.

“Why do they not just fly between?” Cerridwen grumbled. Cedric did not reiterate the danger of their situation; if she did not realize by now how very close to Human discovery they were, she would never realize it.

Bauchan was the head of the three Faeries that joined them on the little boat. He looked them over with a bland expression. The two that followed him flanked the walkway, as if guarding it. Perhaps they were meant to stop them from rushing onto the ship without permission. Cedric smiled at that. Only someone like Bauchan would feel the need to make such a display of strength, someone who had so little to begin with.

“I was expecting Flidais,” Bauchan said finally, with a little shrug, as though he was not as put out as he had expected to be and was a bit relieved at that. “Where has she gone?”

“Dead.” Cedric answered, and prayed the ferryman would not know enough to correct him. “Along with Queene Ayla.”

“I am sorry to learn of her passing.” Bauchan bent his head in reverence. “She must have been prepared for the consequences, though. Anyone who chose to stay in the Underground must have realized it was suicide.”

From the corner of his eye, Cedric saw Cerridwen stiffen. He reached for her arm, took her hand at the wrist, hoped it would be enough to signal how crucial calm was at this moment. “Queene Ayla understood the danger, but thought it cowardly to abandon her subjects. It was her last wish for your good Queene to take the Royal Heir into her protection.”

“The Royal Heir?” Bauchan’s eyes, instantly alight with greed, fell on the unlikely shape huddled in the blanket. “We have met before, at your mother’s audience,” he said smoothly, bowing before her. “It is an honor to be in the presence of so great a beauty again.”

Cedric cleared his throat. “She is wounded, and will need healing. There is only so much that mortal medicine can accomplish, and I fear that limit has been reached. Also, she comes with this small entourage of advisors. I trust that this will not be an imposition, either.”

“Advisors? What need has the Royal Heir of advisors, if she is entrusted to my kind and attentive care?” Bauchan looked over the guards with a critical eye. He was looking for the trick, for some crack in the lie, but he was not intelligent enough to see it beyond the wealth on the Faeries’ backs.

“She will need help managing the meager fortune she brings to sustain her, of course. And one cannot expect the Royal Heir to personally handle the duties of setting up a new—if somewhat diminished—household in Queene Danae’s Colony.”

“Yes,” Bauchan agreed, smiling what must have been the single most insincere smile in the history of all the Fae. “I do think it will be quite a change for her, but a positive one, for all involved. Queene Danae will not see this as an imposition, but a blessing for her Court. And you, were you not one of Queene Ayla’s advisors? Do you wish to maintain that position within the Royal Heir’s household?”

Cedric remained stone-faced in contrast to the Ambassador’s oily graciousness. “Your kindness is appreciated. I travel with the Royal Heir not as an advisor, but as her betrothed. It was decided not long before your arrival at Queene Ayla’s Court that Cerridwen and I should be mates, and the Queene thought it would be in the interest of all involved if such an agreement was not thrown over just because of present dangers.”

Bauchan’s smile faded a little at that, and it pleased Cedric. No doubt that upon setting eyes on the Royal Heir, Bauchan’s mind had spun with all the possibilities for advancement that such a prize could bring him. He’d likely already imagined the reward he would get from Danae for delivering the direct Heir to Mabb’s throne. From there, it was a simple seduction and a carefully constructed revolt to overthrow Danae and make Cerridwen Queene, and him to rule as King beside her. It did not surprise Cedric that Bauchan would be among the many who would seek to gain from the tragedy of Queene Ayla’s death.

Perhaps that ambition would cool a bit in the face of competition, though Cedric doubted it was so.

“I congratulate you both on your good fortune. Rarely have I ever seen so splendid a match.” Bauchan bowed again, and Cedric was certain that the Faery vowed it would be the last time. There was such an air of finality in the gesture that the Ambassador might as well have stamped his feet out of disappointment.

“Then, we are welcome at Queene Danae’s Court?” Cedric motioned to their meager group as a whole.

Bauchan waved a hand. “Of course, you are welcome to join our trooping party. We have very little space, so accommodations will be quite…cramped. And we will be long at sea. Five days, perhaps more, they tell me. But you are lucky, to come to us so close to our departure. The rest of us have been languishing here in the harbor, ready to fly into the hands of the Enforcers by choice.”

Bauchan nodded to the ferryman and pressed something into his hand, but Cedric did not see if it was adequate payment. Guiltily, he did not pursue the issue. They had so little, themselves, that paying the Human seemed a burden. At least he’d gotten something of value for his troubles. Cedric nodded to him as they filed up the walkway.

Bauchan walked ahead of them, and Cerridwen behind him. Cedric noted the way her shoulders hitched as she breathed, the way her feet shuffled, uncertain, on the narrow plank. Two rails fell easily at waist level, and she clung to these as though they alone kept her from plunging into the waters below.

“Easy, now,” Cedric murmured close to her ear. “Stay steady, and you will soon be back on surer footing.”

She blew out a shaking breath and nodded, increasing her pace incrementally.

“You have already had a run-in with Enforcers, then?” Cedric asked Bauchan, tightening his grip on the railings himself as the plank shook from the weight of the guards behind him.

Ahead, Bauchan had nearly reached the opening in the other ship. It was as if the unstable Human contraption did not worry him in the slightest—he had lighted across it as though it were a fallen log on the forest floor.

“No run-ins yet, thank the Gods,” he answered, waiting for them in the muted light from the doorway. “They have been aboard the ship, but we are well concealed, should they raid. A few of the earlier refugees from your Court have not made it, or so we hear, because Enforcers were out on patrol.”

Cerridwen made it to the end of the walkway, and eagerly accepted the arm that Bauchan offered her. Too eagerly, Cedric judged. It was out of fear, he knew, but he wished she would not provide any further fuel for whatever twisted schemes the Ambassador no doubt entertained in his fevered brain.

Once Cedric joined them on the ship, Bauchan relinquished his hold on Cerridwen’s elbow, and smiled at her warmly. “There, no need to fear. Our hosts aboard this vessel care very much about their cargo. They do not undertake a mission from my Queene lightly.”

Cerridwen did not answer him.

“The Royal Heir is very tired,” Cedric said, pulling her close to his side. “Are you not, my…flower?”

She looked up sharply, confusion and anger on her features. Then, as if in defeat, she nodded. “I am. Very tired. Ambassador Bauchan, if you would please show us to our quarters for sleeping—”

“Quarters.” He laughed. “Oh, I wish I could offer you such luxury. We are all bunked in the lowest hold. Though I am certain some arrangement can be made for your privacy and comfort, given your station. I do hope you do not come to us with high expectations for this voyage. It is a meager freight ship, after all.”

“I am sure that she wishes for nothing more than a flat place to lie and a blanket to keep warm.” Cedric chuckled as heartily as he could manage and plucked at the coarse material that covered her shoulders. “And we have half of that already.”

She jerked away and pulled her blanket tighter, as if it were armor. He’d made her angry, that much was obvious, but he did not have the energy, nor the inclination, to soothe her now. Nor was this the proper place, as soothing her would only bring to light a weakness of character in her.

Bauchan led them through a round door a Human would have to stoop to pass, and bade them watch their steps. “These Human vessels are built so strangely. The stairs are steep, and there are constantly barriers underfoot.”

“Give me an old wooden craft any day,” Cedric agreed as they followed him down the narrow ladder, just glad that he wasn’t returning to the depressing concrete surroundings of the Underground.

The lower hold was vast and open, brightly lit, and cluttered here and there with huge steel containers anchored to the ship with heavy straps that bolted to the floor. It was by no means crowded with cargo, but it was crowded with Faeries. Many of them, Cedric recognized from Court, but by their faces only. They no longer looked as fine and self-important as they had when Queene Mabb or Ayla ruled. They wore rugged traveling clothes and crouched protectively over bundles, saying little to anyone but the three or four Faeries who might share the small spaces they had staked out as their own.

He had not seen Faeries behaving so distressingly since he’d stayed on with the Winter Court, long before the Veil had torn. The summertime had always been a time of celebration and plenty, and he’d continued to travel with Mabb’s trooping parade long after the fires of Samhain had extinguished. But with the turning of the year had come a stark, depressing change over most of that Court. They’d become greedy, distrustful hoarders.

As if sensing his thoughts, Bauchan nodded, but he did not comment on the scene. “I know exactly where you will be comfortable,” he declared, striding across the metal floor, his footsteps ringing out as he went. “Back here, this little corner is perfect.”

The space was small, barely long enough to lie down in, but it was protected from prying eyes—and prying ears, hopefully—by two of the large cargo containers and the side of the ship. The guards would have to find another place to rest, ideally not too far from them, but at least it would offer some hope of keeping the Royal Heir safe and away from the betrayers of the Court.

“Here?” Cerridwen sniffed the air and made a face. “It is so dark back here. And close. I do not like close spaces.”

“You skulked about sewage tunnels with your Elf,” Cedric said quietly, near her ear so that only she would hear. “You can deign to sleep here.”

“I will bring you some extra blankets,” Bauchan went on, as though she had never argued. “The crew has been exceedingly generous with their things. They are…sympathetic to our plight.”

“Our plight.” Cedric could not help but scoff at the words. Then, he waved an apologetic hand. “Forgive me, I am tired.”

“Of course.” Bauchan bowed, like a Human fop. “If that will be all, then, I can have your companions settled, as well.”

He would not give them a moment alone to confer. Already, he suspected some plot, saw that the guards were not truly the nobility he had dressed them up as.

One of the guards puffed up his chest and clutched the satchel he’d carried tighter. “I do not wish to seem ungrateful,” he began, in tones that sounded comically similar to Bauchan’s, “but it does not appear as though our—we courtiers—our possessions will be safe among the rabble.”

Cedric spared a glance toward Cerridwen. She stared, mouth agape, at the guard, broken out of her sullen reverie for a moment. It was almost enough to make Cedric laugh.

“You could leave your things with us, then,” he offered, quickly stifling the amusement that he was certain had shown on his face. “We seem to have a most isolated spot, and of course you can trust the Royal Heir.”

The guard played it hesitant; time at Court had afforded him an uncanny ability to imitate the behavior of his “betters.” Finally, with a heavy sigh, he handed over the satchel. “From the looks of things, I would advise you all to do the same,” he said with a courtly flourish as he stepped aside. The others entrusted “their” belongings to Cedric a bit too easily, but Bauchan would not argue. It would not have been Court manners.

“What a generous offer,” the Ambassador said with a smile as sickeningly sweet as spun sugar. “You are truly fit for your role as Royal Consort.”

“Let us hope it should never come to that,” Cedric said with a humble bow.

Bauchan, the rage practically radiating from him, returned the gesture and quickly ushered the guards away.

When Cedric turned to Cerridwen, she had already lain down, the blanket pulled sullenly over her face.