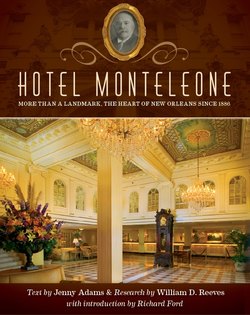

Читать книгу Hotel Monteleone: More Than a Landmark, The Heart of New Orleans Since 1886 - Jenny Ph.D. Adams - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION by Richard Ford

ОглавлениеMy most enduring memory of the Monteleone— and my most endearing—must’ve originated about 1950. I was six. It was a typical shoe-leather-melting summer day in New Orleans. My mother, to while away the steamy hours and divert her only son, had been taking us back and forth across on the Algiers Ferry for most of an afternoon, letting me stand up in the bow, breathing in the hot, complex, brackishness of the river, watching the city’s modest skyline move away, then draw close again, move away, come near, move away. Pralines are a central feature of this memory. They were on sale at the ferry dock, packaged in small, waxy sleeves, and sold for a dime.

At five sharp, however, we quit our journeying and walked hand in hand up Canal Street, the short stroll to Royal and down the shadowy block and a half to the Monteleone, which was my father’s “headquarters” when he worked his south Louisiana accounts—Schwegmann’s and Delchamps in town, and all the small wholesale grocer concerns down through Houma and over to Lake Charles, up to Villeplatte and Alec, and back again. He sold laundry starch. Faultless. It was a name that meant something then. He’d be waiting for us in the hotel.

When we arrived, we found him seated on a stool in the Carousel Bar, just to the right, inside the hotel entrance where it still is today, its windows facing onto Royal to let the patrons watch the world go by outside from within, where it’s cool. My mother and I sat down beside my father at the circular bar. They were happy to see each other after a long hot day apart. Our family was only the three of us. But my father had a look of consternation on his long Irish lip, and his brow was furrowed, a familiar expression that meant things weren’t going well. “Carrol, what’s the matter?” my mother said. “You look worried.”

“I don’t know.” My father shook his head as if to exhibit confusion. “I’ve just had one drink. But I guess it made me drunk. Because when I came in here twenty minutes ago, I sat down at this bar and I could’ve sworn I was facing the door—so I’d see you. But now I’m facing the window. I don’t know what’s happening to me.”

My mother told this story with relish all her life. I suppose I’ll tell it all of mine. To her it proved what a sweetly guileless man my father was, a country boy, unsophisticated in the ways of big cities, trusting to how things should be, not so sure about a world where the elegant bar in a swell hotel could imperceptibly make a complete revolution every fifteen minutes, taking its unsuspecting tipplers along for the ride; a ride they might not—if they were my father—even notice they were taking. Carousel. The name might’ve suggested something, but didn’t. That guilelessness was partly why she loved him all her life. I always have a drink there when I’m around, think sweetly of the two of them all those years ago in the Monteleone.

I guess one has to say—in view of memories like mine—that the best thing today about the stately old Monteleone (now 125 years young) is that it’s still here, its latch-string still on the outside, its brassy doors still swinging open to drummers like my father, to vacationers down from Des Moines, newlyweds overnighting for a slice of heaven, legislators cutting midnight deals, executives with their secretaries in tow, Arab sheiks, movie types, goateed jazz-men, gigolos and gigolettes, the odd writer needing refuge to polish his story in a room that sees the river. If you would read closely, at the conclusion of Eudora Welty’s magnificent New Orleans story “No Place for You, My Love,” you’d see (at least I see) the heroine of this sumptuous, passion-streaked story, alighting from her lover’s convertible and disappearing through the revolving doors of a hotel. It’s this hotel. It could scarcely be any other.

So, yes—or no. The Monteleone’s still here after 125 years, cradling my memories and a million others’. It hasn’t fallen to the greed and stingy imagination of the entrepreneurial spirit and its dumb wrecking ball, which only seems to clear a way for hotels of ersatz grandeur and unnuanced chrome and glass predictability that calls itself hospitality. Me— the inveterate stayer in a thousand hotel rooms in my life—I’m on the run from those spiritless places. And where I run to is here.

Oh, there used to be hotels like this one—or at least close: old, family-owned, family-run accommodations all across the south, all across America. The Muehlebach in K.C. The Peabody in Memphis. The Marion in Little Rock. The Edwards in Jackson. The Bentley in Alexandria. The Drake in Chicago. A few persist today, it’s true: genuine hotels—not “venues,” not “properties” with corporate ice in their veins and precisely planned obsolescence; but honest-to-God establishments, where arriving and checking in was a ceremonious event all its own, with public-private formalities and rituals and assumptions and a cast of memorable employee-characters that all joined in declaring to the weary traveler or the grinning, winking old pol or the young bride and groom: “You’re not at home now. This is special. You’re our guest, not just a customer. We offer comfort and privacy for whatever you require comfort and privacy for. But we’d also like you to feel you belong here, at least for a while.”

Obviously I’m a romantic when it comes to these splendiferous old piles and their gilded trappings—chandeliers and chimes, goldfish ponds and red damask wall coverings, liveried this’s and that’s. I hope I won’t live long enough to see them go extinct. Later in my boyhood I actually resided in one, and in my time I saw parade before me a thousand florid stories, characters, spectacles—a great Scheherazade of a place, featuring (it seemed) the world’s moral miscellany passing every day: pathos, transgression, charity, humblings large and small, unsavoriness and kindness of every stamp. Much of it extremely funny. Not a bad beginning for a boy on his way to be a writer. And I’ve lived long enough to see even that old place of my boyhood torn down, imploded, and a gleaming new ziggurat rise from its rubble. The Excelsior, they called the new place. Quite glittering. And now it’s gone, too, after only thirty years, replaced by something different— all my faithful memories left with no firm locus on which to fix themselves, just afloat, surviving in my dreams.

Which brings me quick to the end here—and you to the beginning.

Best of all worlds? Near the other end of life now, I’d like to live here (again, as it were), maybe just down the hall from where you are today; make permanent and caressing what’s so fleeting and rare—the ceremony, the observance and protocol, the sense of affirmation that a place like the Monteleone confers. A certain kind of estimating, untrusting man wants to live out his winter years discreetly in a good hotel—where Al the bellman knows your name, where the bartender pours your drink before you even get there, where the sheets are crisp each night and the towels plentiful and fresh, your breakfast eggs are poached perfect each morning; and where, when you step out onto Royal Street to calculate the day, the doorman steps up with a grin and says, “Another beauty, Mr. Ford” (whether it is or it isn’t). I could let time ease by that way, you bet I could—which is to say timelessly, barely noticed—the way it passes in a good story that you read again and again and again, always wanting more.

Richard Ford

1215 Burgundy Street

New Orleans, 2010

Antonio Monteleone (1855–1913).