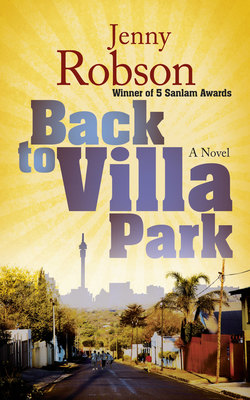

Читать книгу Back to Villa Park - Jenny Robson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеNick the Greek

After Ma came back from the clinic, around when I was eleven-and-a-few-months, I used to go to Nick the Greek’s butchery often. Ma couldn’t do the shopping. Well, most of the time she couldn’t get out of bed. So I went to buy the food instead. Just about every second day, soon as I’d changed out of my school clothes.

Nick the Greek was a nice man. I don’t think he really was Greek. I don’t even think his name was Nick. That’s just what Ma called him.

Let me tell you, it was a bad day, that day Ma ended up getting taken to the clinic. I was just home from school, taking off my blazer in my bedroom. Then I heard her screaming and the sound of glass smashing.

She was there at her dressing table. It was a very old dressing table that came from Ouma’s farm. Ma always polished it with special oil and I wasn’t allowed to fiddle with the fancy brass drawer handles.

“It’s antique, Dirkie. Real red Rhodesian teak. Your ouma got it for a wedding gift. It’s worth a lot of money, see? We must take special care of it.”

But now there she was, in her yellow dressing gown, smashing at the mirror with her hairbrush. There was already a huge crack down the one side.

“Don’t you come near me,” she screamed. “Voetsek, voetsek! Don’t you dare touch me!” Like she was seeing someone in the mirror. She screamed the K word too. Over and over. That was quite a shock for me. She never used that word, even when she was checking the burglar bars at midnight. Nor my dad. They were always making sure I knew not to say it.

“It’s not a nice word, Dirkie. It makes black people very upset if you say it,” Dad told me. “It’s a kind of swear word. You know, like the F word or the C word. You’ll get into trouble if you use it.”

I knew about the F word, of course. Some grade seven guys said it a lot in the playground. I didn’t know about any C word, but I thought it was better if I didn’t ask. But here was my ma, yelling the K word, and I was so worried she would get into trouble. But I didn’t know how to stop her.

I suppose it was neighbours that called my dad home from work. And then maybe my dad phoned for the ambulance. I don’t remember too well. Except for the two big black men in their white jackets.

They half carried her down the driveway of 5 Groenewald Street, and she was screaming the K word at them, telling them to voetsek. But they just laughed. One of them said, “It’s alright, Mrs Strydom. We’ll take care of you. Don’t worry about a thing.”

Then she started yelling, “A-N-C! A-N-C!” over and over. But in an Afrikaans accent so it sounded like: “Aah. En. See-ya!”

And of course there were neighbours standing on their stoeps and out in their front gardens or even in the road to watch. All the way up and down Groenewald Street.

I mostly remember Jimmy Big-Deal Cameron from number 12. He was two years ahead of me at Villa Park Primary. Rugby captain. Deputy head boy. And there he stood staring, next to his mother, who was dressed up like she was on her way to church or something. Around them were all the fancy flowers she grew, even outside their fence.

I wanted to shout the F word at them. But then maybe the two black men would lift me into the ambulance too. So I just stood quiet beside my dad there at our front gate. Dad had his arm around my shoulder. I could feel how it was shaking. I suppose because even buying Ma a bright-yellow dressing gown hadn’t made her feel better.

*

When Ma came back from the clinic months later, she mostly lay in her bedroom with the curtains closed. And she had to take lots of pills.

That’s why Dad found Dorcas to come and work for us.

Dorcas September.

“You must be polite to her, okay, Dirkie?” my dad said. “We really need her now. She can cook.”

But I hated Dorcas right from the start. Just the way she looked at us and walked around our house like she was laughing at us. I caught her out too. I got back from school and the vacuum cleaner was going in the lounge, making that horrible sound vacuum cleaners make. But when I looked into the room, Dorcas wasn’t cleaning. Hell no!

She was just sitting there on our sofa with the cushions all round her, watching SABC 2 on the TV, knowing Ma wouldn’t get out of bed to come check. And the brush end of the machine was just lying there, howling and sucking in fresh air. Wasting our electricity for nothing!

I told my dad, but he didn’t do anything.

He said, “Don’t upset the maid, Dirkie. Ma needs lots of help right now and I can’t take more time off work to find another maid. So just leave things be, okay, Dirkie?”

Like I was the one causing the problem!

But at least Dad wouldn’t let her move into our maid’s quarters outside the back.

She begged and begged.

“Ag, asseblief, masser, what else must I do? My daughter is alone in my house every day with the school holidays. There are bad men there, masser, all around the streets. I must worry all the time. How can I work properly when I am worrying about my child? Those bad men, they will rape her, murder her, leave her body in the bushes … And your back room is empty. Just some old boxes and newspapers. Ag, asseblief!”

In the end my dad said Dorcas could bring her daughter with her to work every day in the school holidays. I think he even gave her extra taxi money.

So this girl used to sit there, this Janie September. There on the steps of the maid’s quarters, beside her mother’s huge brown bag while her mother worked in our house.

Or pretended to work.

Sometimes I looked out of my bedroom window to see what Janie was up to. Mostly nothing, just sitting there, twirling a lock of her long, curly hair round and round her finger. Staring round our backyard with her eyebrows high on her forehead. Or else reading torn pages from old newspapers and magazines she found in the maid’s room around the pile of boxes. My sister, Fat Sonya, left the boxes when she and her husband, Fatter Koos, moved down to that pineapple farm near Port Alfred. Sonya kept promising that Fatter Koos’s brother would come pick them up. But he never did.

*

This morning at Kagiso Holdings I didn’t recognise Janie September at first. Well, she looked familiar, but I didn’t remember where I’d seen her before. Not for a long time.

Well, I was in such shock, I wouldn’t have recognised anyone. I opened that door expecting to find the manager of Kagiso Holdings sitting behind a big desk. Expecting that he would tell me to sit down in a nice soft chair so he could ask me questions. But what did I find instead? A whole room filled with other guys, all wanting to earn while they learned.

For a moment it felt like I was back in the classroom at Port Alfred Secondary.

I just stood there in my clean shirt that Mrs Mogwera had ironed for me, with my new blue tie round my neck.

Some guy in the front said, “There’s empty desks at the back, bra.”

But there was only one empty desk, right in the back corner. And I had to walk past all these guys who were staring at me. At last I slid into the desk. And there was this girl right beside me, a Single A. She looked at me once and then turned away, like I was nothing very interesting. But I knew I’d seen her before. Was she maybe from Villa Park Primary?

I looked sideways at her a few times. She had these eyebrows, thin and curved high on her forehead as if she was surprised. But I didn’t have time to think. Mr Nkum-whatever came swaggering into the room with his fancy suit and his loud, arrogant voice, talking about test papers and joking with all the other Double As in the room.

*

Dorcas mainly cooked frikkadels and mashed potatoes. Ma sent me out after school every second day to buy mince. She said she didn’t want the maid handling her money.

“You go to Nick the Greek, Dirkie. I want fresh-cut mince. Not that packaged stuff from the supermarket. And it must be topside mince, you hear me?”

In the half-dark bedroom with the curtains pulled shut, it was hard to see Ma properly. She had her handbag lying there next to her always. By the time she had found the money, she was exhausted again. And before I was out of the room she was lying back against the pillows with her eyes closed.

But I was happy to go. I walked down Groenewald Road, then along Pine Street almost to Northfields Play Park. Then left towards the robots and the Pick n Pay mall.

Nick the Greek was always nice to me. Like I was an important customer.

“Aah, yes. And Mrs Strydom, your mother, she wants I must cut from the topside? She knows what is the good mince. Always she says to me: you must cut from the topside. Only from the topside. I hope she is getting better now. You tell her I send good wishes!”

Nick the Greek spoke on and on while he weighed the meat and then put it through his machine. And wrapped it up in soft white paper. And then the best part came. He took out his special polony and machined off a thin slice for me. So thin you had to hold it carefully so it wouldn’t tear.

“Your bonsela, yes? You come to me again, yes?”

It was the best polony I ever tasted. A soft pink colour, not that ugly bright pink you get at other shops.

I carried the polony in the palm of my hand. I ate it slowly, only one small bite every twenty steps. That way it lasted all the way back to number 5 Groenewald Road.

But even if the mince was cut from the topside, Dorcas’s frikkadels always tasted horrible. Even Dad thought so.

We sat together at the kitchen table in the middle of this lake of green lino. It was the new lino Dad got for the floor while Ma was in the clinic: curling green ferns. He said green was a calming colour.

Sometimes he spoke to me.

“I’m worried, Dirkie. I can’t deny it. They’re talking about redundancies at work. I mean, I’ve been with the firm twenty years now. How can they think about chucking me out? Like I’m a dog! Is that fair? Hell no!”

The frikkadels tasted more like bread than meat. They clogged up on the roof of my mouth like paste.

“But don’t say anything to your ma, okay, Dirkie? We mustn’t upset her, not when she’s doing so well. I’ll have to start looking for another job. It won’t be a problem. I’m only forty-one. Definitely not over the hill yet. Right, son?”

I went to the sink for a glass of water to try wash down Dorcas’s frikkadels. Dad didn’t finish the three on his plate, even though he put on so much chutney. Even though Nick the Greek had cut the mince from the topside.

“Cut from the topside!” Dad said. “Hah! That’s a joke! It’s not just the mince that got cut from the topside, my boy. It’s us as well.”

*

So. Okay. I slipped my bloody tie into my pocket and got into the taxi for a ride to Villa Park Mall so I could sit with Aggies for a while.

It was a good taxi ride, at least. Under Pressure: that was the taxi’s name. But I didn’t feel under pressure. In fact the ride helped me recover a bit from the stuff that happened at Kagiso Holdings.

Sometimes being in a taxi is horrible. The other passengers stare at me like I don’t belong there. Like, what is this lekgoa, this white boy, doing in our transport? They hold themselves stiff so they don’t have to touch me. As if I have a disease or something.

I get angry. This is public transport, right? And I am public just as much as they are. What do they expect? That I must walk everywhere just because I am a Zed? Hell no!

But Under Pressure wasn’t like that. The driver even called me “brother”. That made me feel good. Calmer.

The lady next to me gave me a tissue for my knuckles. I told her it was my birthday. She smiled and made her earrings swing and said, “Happy birthday, then. How old?”

“Eighteen.”

“Only eighteen? You look much older. Like maybe even twenty-two.”

Bethany also thought I was older when I first met her.

“Only seventeen?” she said back in March. We were in her bathroom and she was giving me a clean towel so I could get dry after my hot shower. “Okay, but listen. You tell the other guys that you are, like, twenty-one. I don’t want them thinking I am, like, some cradle snatcher!”

But she still wanted me in her bedroom after the shower. She still expected me to act like a 21-year-old. And when I didn’t, she got quite mean and sarcastic. And asked me if I was gay.

So. Okay. I got out of the taxi at the mall robots. The woman with the earrings called after me. Said I must have a special day.

And there was my friend Aggies. Where he always sits, leaning his back against the third concrete pillar. Exactly opposite the shop that used to be Nick the Greek’s butchery. Exactly where he was the first time I met him back in January.

Aggies smiled up at me so his four teeth showed: two at the bottom right, two at the top left. Those are the only teeth he has. They always make me think of Afrikaans quotation marks, you know for direct speech? We had a teacher in grade six who was always going on about that, like it was the most important fact of the year. It’s the only thing I still remember from grade six. And grade seven for that matter. I wasn’t very good at school. Not like James Big-Deal Cameron, who ended up getting prizes for everything at prize-giving.

But even if Aggies has quotation marks in his mouth, he doesn’t speak very often. Mostly he listens. Well, except for the time when he told me about his three children and the terrible thing that happened to them. But that took him nearly a whole night. And Rosie had to keep explaining the stuff he left out.

I slid down the pillar to sit next to him with the morning sun shining right in my eyes. There were just a few coins in his safari-guide hat.

I said, “I didn’t get a job with Kagiso Holdings. How’s that? It’s my birthday and they still didn’t give me a place.”

Aggies made soft sympathetic noises while I told the whole story.

A passing Pick n Pay customer with her trolley overflowing dropped two five-rand coins into his hat. That’s when Aggies spoke.

“God bless you, missus. God shine his face on you and be gracious unto you.”

I said, “Maybe later I’ll go see Bethany.”

“It is good,” he said. “A man must have a woman.” He always says that. Even though Rosie is drunk most of the time. Even though she calls him the C word and the P word. And the K word.

“Yes, a man needs a woman. That is the way the world is,” he said, and he gave me the two five-rand coins for my taxi fare.