Читать книгу Gabriel and the Phantom Sleepers - Jenny Nimmo - Страница 8

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

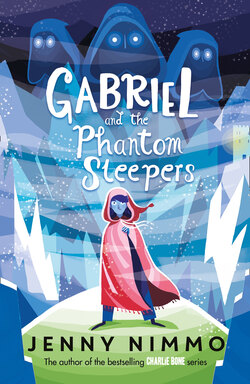

The Hooded Stranger

The invitation sat on a shelf above the kitchen stove. It was edged in red and gold, and printed in an ornate, ancient-looking script. It said:

‘You are honoured to receive this invitation to:

A fantastical convention of the alchemists’ society.’

At the bottom of the card in small print was a date and the name of an obscure town in Belgium.

Mr Silk’s name was handwritten at the top, and he was forever looking at it and smiling to himself. The rest of the family tried to ignore it, especially Mrs Silk, she couldn’t be doing with alchemy or any other fantastical activity. She put up with her son, Gabriel’s, seventh sense only as long as it didn’t affect his three sisters.

Gabriel was secretly pleased about the invitation, but also a little nervous, for it meant that, while his father was away, he would be Keeper of the king’s cloak for a whole week.

Mrs Silk had made a firm promise to take her three daughters to visit their cousins, but Gabriel wanted to stay with his Uncle Jack and cousin Sadie instead. There was simply no room for him at his Aunt’s place.

The cloak couldn’t be left in an empty house, so it was decided that Gabriel was the best person to take charge of it. After all, no one would believe that a mere boy would be in possession of such a garment.

Today there was chaos in the Silk household. The girls were upstairs preparing for their holiday. There were arguments over clothes, bags of toys, shoes (lost and then found), crisps, car-seats and even bananas. Sylvie was eight and Sally a year younger. Bonnie was five and had the loudest voice. Gabriel was twelve.

‘You can still change your mind,’ Mrs Silk told Gabriel.

Gabriel grinned and shook his head.

‘I don’t like to think of you going all that way with the cloak,’ went on Mrs Silk, ‘but I promised my sister I would visit, and the girls are dying to see their cousins.’

Alice and Annie were the same age as Sylvie and Sally.

‘There wouldn’t be room for me,’ said Gabriel, ‘and anyway Dad’s friend Albert will be travelling with me, all the way.’

Mrs Silk sighed. ‘If only Dad didn’t have to go to this wretched convention. He’s not even an alchemist.’

Gabriel rolled his eyes. ‘But it’s an honour, and he’ll get loads of ideas for his books.’

‘So he says,’ muttered his mother, tight-lipped.

Sylvie burst into the kitchen, waving a pink bag. ‘We’re ready,’ she cried.

Gabriel and his mother went out to the car. Arguments over, the girls were waiting happily beside it. After many hugs and wet kisses, Gabriel and his father watched the girls pile into the car. There was a loud toot, much waving and then Mrs Silk’s car was bumping down the muddy lane.

It was time for Gabriel to begin his own journey. But first – the cloak. He followed his father upstairs. Mr Silk had already taken the cloak from its hiding place in the attic. It was lying on Gabriel’s bed. The cloak might have been a thousand years old, but its original bright crimson had hardly faded, and when Gabriel half-closed his eyes he could see tiny stars glittering on the hem. No harm could ever come to the wearer of this garment, but as it was such a priceless treasure the Silks had to keep it as safe and secret as they could.

Mr Silk folded the cloak and rolled it in an old jacket. He placed the jacket on top of a thick sweater in Gabriel’s travelling bag and zipped it up. ‘Albert will keep an eye on things,’ he said cheerily, ‘and when you get to Uncle Jack’s the cloak will be quite safe. Your uncle never leaves the house.’

‘Poor Uncle Jack,’ said Gabriel.

‘Wicked woman,’ muttered Mr Silk, referring to his brother’s ex-wife, ‘leaving him under such a monstrous spell.’

‘D’you think she’ll come back?’ asked Gabriel.

‘Not a chance,’ said his father.

‘Sadie said she was living in a Russian castle, the last time they heard.’

‘There you are then. Come on, Gabriel. Have you got everything you need?’

Gabriel eyed his bag. ‘I hope it won’t be stolen on the train.’

‘There’s no fear of that.’ Mr Silk patted his son’s shoulder. ‘Very few people outside the family know about the cloak. Albert knows, of course, but he’s my oldest friend.’

‘Charlie Bone knows, and Tancred and Emma, and all my friends at Bloor’s Academy.’

‘They are family,’ said Mr Silk. ‘They’re the Red King’s descendants, too.’

‘Are you sure you don’t want to take the cloak to Belgium with you?’ Gabriel asked.

‘To an alchemists’ convention?’ Mr Silk shook his head. ‘It’ll be crowded with sorcerers and their like. They’d sniff it out in no time.’

‘You said that very few people can wear the cloak safely.’

‘Indeed,’ said Mr Silk. ‘But who knows if this applies to sorcerers. Come on, let’s get you to the station. I’ve got a plane to catch when I’ve seen you off.’

Gabriel picked up his bag and followed his father downstairs. In the hall he shrugged himself into his anorak, while Mr Silk put on a grey woollen coat. It made him look far more important than he usually did. He was a small man, with thinning, sandy hair, mild grey eyes and rimless spectacles.

Gabriel didn’t resemble his father in the least. He was tall for his age, lanky and dark. His hair had a habit of flopping over one eye and Gabriel was happy to leave it that way.

When Mr Silk opened the front door the mistletoe over his head swung wildly in a cold breeze. It was only three days after Christmas.

The train station was quiet, their platform deserted. But on the other side of the rails a few passengers stamped up and down, trying to keep warm. All were travelling south.

A blast of freezing air bowled dust and paper down the platform. Wind from the north, where Uncle Jack and Sadie lived. Gabriel turned up his collar. Soon he would be travelling into the mountains and the icy home of the north wind. But Sadie would be there, cooking wonderful things to eat.

Ten minutes passed.

Mr Silk kept staring at his watch. He was beginning to look anxious. ‘Train’s late,’ he muttered. He paced up and down the platform, his hands in his pockets, whistling. There was a note of unease in the whistles. ‘The train can’t have gone through already,’ he said. ‘We were here in good time.’

‘Perhaps it’s been cancelled,’ Gabriel suggested.

His father looked even more worried. ‘No, no, impossible. I’ve got to go soon, Gabe. I must get to the airport in time.’

Another ten minutes passed. Mr Silk took out his mobile and called a number. ‘Ugh. I’m not getting through,’ he said. ‘They’re probably in a tunnel.’

A few minutes later his phone rang. He pulled it out of his pocket and held it to his ear. ‘Albert!’ he said. Scattered sounds came from the mobile and Mr Silk replied, ‘Great! Sorry to miss you, but Gabriel’s here, all ready with the –’ he glanced over his shoulder – ‘you know what.’ After another short burst of sound, Mr Silk said, ‘Good! Good! Catch you in the new year, Albert. Thanks for this.’

‘Is your friend . . .?’

‘He’s on the train, but he got the time wrong. It’ll be another fifteen minutes, and I must dash, Gabe, or I’ll miss my plane.’

‘Aren’t you going to –’ Gabriel began.

‘Sorry, son, I’ve got to go. Albert’s nearly here. You’ll remember him when you see him. Big man, white moustache. He’s going to be wearing a black hat. My oldest friend. You’ll be fine.’

‘I’ll be fine,’ Gabriel repeated. He wished the phrase didn’t have a whiff of bad luck about it. ‘Bye, Dad. Have a good convention.’

‘I will. Bye, Gabe.’ Mr Silk patted his son’s shoulder and walked briskly to the exit. He gave a quick wave and left the station.

Gabriel clutched his bag. He looked over his shoulder, then up and down the platform. A woman in a red coat was now sitting on a bench quite close to him. Gabriel thought she had been staring at him. She quickly glanced away.

The minutes ticked by. Gabriel kept consulting his watch. He had never known fifteen minutes to last so long. On a sudden impulse, he pulled out his phone and rang his friend, Charlie. There was no reply. Gabriel remembered that Charlie was in some far off place with his cousin, Henry. He tried Tancred Thorsson’s number.

‘Hi, Gabe,’ came Tancred’s cheerful voice. ‘How –’ His next words were drowned by an explosive sneeze in the background. ‘Dad’s got a cold,’ Tancred explained. Gabriel could hear things hitting the floor – tins, perhaps, or knives – and then the smash and tinkle of glass. ‘Another window’s gone,’ said Tancred calmly. In the Thorssons’ house it was an almost everyday occurrence.

Tancred and his father were weather-mongers, they could muster up wind, rain, hurricanes, thunder and lightning at will. The trouble was that these powerful elements could also arrive unbidden, especially if the Thorssons were anxious or unwell.

‘Are you OK, Gabe?’ asked Tancred when the noise had died down.

‘I’m OK,’ said Gabriel. ‘Are you?’

‘Yes, yes. I’m fine,’ Tancred replied, and then he sneezed.

‘Bless you,’ said Gabriel. ‘Oh, I think I can see the train.’

‘OK, Gabe. Bye, then. Have a great time in the north.’

Gabriel was reluctant to let his friend go, but the train was drawing closer. Gabriel hardly had time to get his mobile into a pocket, before three carriages squealed past him into the station. A man leaned out of a window several doors down. He wore a black fur hat.

‘Gabriel!’ called the man. ‘Gabriel Silk?’

‘Yes. That’s me.’ Gabriel picked up his bag and raced towards the figure in the black hat.

The door opened and a large man stepped down on to the platform. ‘Hurry, hurry, Gabriel.’ The man had a white moustache and wore a grey tweed coat with a black fur collar. Tufts of white hair stuck out from under his hat.

‘Good to meet you, Gabriel,’ said Albert when Gabriel had reached him. ‘I’m Albert Blackstaff.’ He gripped Gabriel’s free hand, shook it heartily and climbed back into the train. Gabriel leapt up the steps after him.

Albert led the way to a seat with a table. There were only two or three others in the carriage, and then the woman in the red coat came in. She looked at Gabriel who quickly shuffled away from her gaze and towards a window seat. He lifted his bag on to the table and sat behind it. Albert took the seat opposite and winked at him. ‘Precious cargo,’ he whispered.

‘Yes.’ Gabriel nodded. He felt foolish because surely no one had followed him, and who was there to steal the bag? Surely not the woman in the red coat.

It was a long journey. Gabriel had been prepared for that, but he found his companion’s silence a bit disturbing. Gabriel had expected him to be a bit more chatty. Almost as soon as they sat down Albert produced a newspaper, shook it out and held it up before him.

Gabriel read his book, an adventure involving pirates and parrots. When he was tired of that, he pulled a bag of sandwiches out of his pocket. They were slightly squashed but still fresh, and Gabriel thought them worth offering.

‘Have a sandwich,’ he said, holding the bag out to Albert.

The big man shook his paper and peered round the side of it. ‘What?’

‘Sandwich?’ said Gabriel. ‘Cheese and tomato, Mum made them.’

‘Ah.’ Albert eyed the sandwiches and frowned. ‘No thanks, Gabriel. I’ll wait.’ He took off his fur hat, revealing a mop of thick white hair. ‘Getting a bit hot in here.’

‘Are you going to Meldon as well? I forgot to ask Dad.’

‘No, not Meldon.’ Albert obviously thought that was enough information.

Gabriel tried to start another conversation. ‘Dad says we met when I was five, but I can’t really remember.’

‘Oh, I can, Gabriel. You were a very bonny little lad.’

‘I must have changed a lot.’ Gabriel hadn’t meant to sound surprised, but he knew he had been anything but a bonny little lad.

‘We all change,’ Albert said cheerfully. ‘Get on well with your Uncle Jack, do you?’

‘He’s OK.’ Gabriel didn’t like to mention his uncle’s problem. ‘My cousin Sadie’s great. She can cook anything.’

‘Anything?’ Albert raised an eyebrow.

‘Well, almost anything,’ Gabriel amended.

‘Ah.’ Albert disappeared behind his newspaper again.

Gabriel ate a sandwich and went back to his book.

It began to get dark. In the weak light Gabriel could see winter trees swaying in a fierce north wind.

‘Looks cold out there,’ he muttered.

‘Mm?’ Albert lowered his paper and, giving Gabriel a friendly smile, said, ‘Get me some tea, would you, Gabriel? Milk, no sugar. And a cake, anything chocolate. And something for yourself, here.’ He felt in his pocket and produced a ten pound note. ‘Get what you want.’ He winked.

Surprised by a second wink, Gabriel took the note and made his way to the restaurant car. He ordered two chocolate muffins, a tea and an orange juice. While he was waiting, the woman in the red coat came in and stood behind him. ‘Be careful,’ she said.

Gabriel thought she was warning him not to spill the tea. He was making his way back to his seat, and just crossing the gap between coaches, when suddenly a man leapt in front of him. Where he had come from Gabriel couldn’t guess. He recoiled from the man’s awful smell, almost dropping his tray. The stranger wore a long, hooded cloak, his pale eyes bulged out of leathery-looking skin and his wrinkled cheeks hung over his jaws like shrivelled balloons.

‘Fool!’ spat the man. ‘Do thy duty.’

‘Gabriel was too shocked to move. ‘Wha . . .? he mumbled.

‘Dost thou forget thou art Keeper?’ grunted the apparition.

‘No . . . no,’ croaked Gabriel.

‘Aiee!’ cried the hooded man. ‘Stop them, or ‘twill be the worse for thee.’

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ said Gabriel, almost tearfully.

The hooded man growled, showing long cabbage-coloured teeth, but all at once a sharp voice said, ‘Leave the boy alone,’ and the woman in the red coat strode past Gabriel. She prodded the stranger in the chest, saying, ‘Go away. Leave him alone.’

A dreadful sound came from the man. A long, gasping intake of breath, followed by a snarl. ‘I will not harm thee this time, Keeper’s friend,’ he grunted, ‘but beware, I can do worse.’ He waved a hand of gnarled, fleshless fingers before the woman’s face, then his eyes rolled back into his head, and he vanished.

Gabriel’s hands began to shake. The woman in the red coat seemed unable to move. She stared at the space the hooded figure had occupied, her hand still locked on to her cup of tea. Her mouth had dropped open and her eyes were wide and fixed.

‘Was . . .? I mean . . . are you?’ Gabriel stuttered.

The woman remained in a sort of frozen state, unable to respond in any way, almost as though Gabriel wasn’t there.

Gabriel felt he should give her a nudge, or pat her hand, anything to shake her out of her trance, or whatever it was, but he was afraid of spilling Albert’s tea. So he just stood beside the woman, who, after all, had saved him from something definitely nasty. ‘Er . . . are you?’ he said hesitantly. ‘No, that’s silly, you’re definitely not all right, are you?’

‘Oh!’ The woman gave a long sigh and turned to Gabriel. ‘Whatever happened?’

‘There was a horrible-looking thing here,’ said Gabriel. ‘It waved its hand and then it kind of vanished.’

‘Of course. How could I forget? You go back to your seat, Gabriel. I’m quite all right now.’

‘Are you sure?’ Gabriel wondered how she knew his name.

‘Yes, yes. But I’m new to the job, and I’d rather you didn’t mention my little – er – moment of weakness.’ The woman had a warm, friendly smile.

‘Who would I mention it to?’ asked Gabriel.

‘Oh, never mind.’ She was quite young, Gabriel reckoned. He thought he’d seen her before somewhere.

‘Better get back to your seat,’ she said firmly.

Albert appeared to be asleep when Gabriel reached him. Gabriel set the tray in front of the big man, muttering that he was sorry he had taken so long.

Albert opened one eye. ‘Muffins,’ he said. ‘Good choice.’

Gabriel handed over the change and slid into his seat. He thought he should probably mention the hooded stranger, but he waited until Albert had munched his way through his muffin before describing the man who had accosted him.

Albert frowned and placed his cup on the table. ‘You should have alerted me before,’ he said.

‘Sorry. I thought you’d like to finish your tea first,’ said Gabriel. ‘I hope it’s not a bad sign.’

‘Who knows?’ Albert looked at his watch. ‘Ah. Time for my medication,’ he said, and he pulled a small travelling bag from under his seat. ‘I’ll just pop to the toilet, Gabriel. Won’t be a tic.’

Gabriel wondered why Albert had to take his bag to the toilet. Perhaps he needed his towel and toothbrush.

Albert was in the toilet for a long time. The train stopped briefly at a station, then rolled on again. Albert still hadn’t returned.

Gabriel leaned back in his seat and the train continued into the night. It was now quite dark outside. Gabriel yawned and closed his eyes. Perhaps he fell asleep, he couldn’t be sure, but all at once he was aware of the nauseous smell of decay drifting under his nose; the air was thick with it. Gabriel sat up and coughed violently.

There was a faint hoot from the engine and the train began to slow down. Slower and slower. Seconds later it stopped altogether. It was very quiet in the carriage. Gabriel peered through the window. Flurries of snow came floating out of the darkness.

‘Snow,’ he murmured.

‘Fool,’ croaked a voice behind him. ‘Now it begins.’