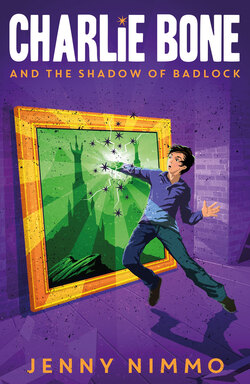

Читать книгу Charlie Bone and the Shadow of Badlock - Jenny Nimmo - Страница 11

The package in the cellar

Оглавление‘Pretty Cats!’

In the hall of number nine, Filbert Street, a small boy stood at the foot of the staircase. He looked sickly and too thin. Scraping a tangle of dull brown hair away from his face, he stuck out his tongue. ‘Flames! That’s what they call you, isn’t it?’

The three cats, sitting on the rail, stared down from the landing above. They had fiery coloured coats: copper, orange and yellow. The orange cat hissed; the yellow cat lifted a paw and flexed his dangerous claws; the copper cat gave a deep, threatening growl.

‘Why don’t you like me? I’m smarter than you. One day,’ the boy raised his fist, ‘you’ll be sorry.’

A door opened behind him and a voice called, ‘Eric, what are you doing?’

‘Come and look.’

Two women stepped into the hall. They would have been identical if there had not been twenty years between them. Both were tall and dark-eyed, with thin, chilly mouths and long, narrow noses. But whereas one had bone-white hair, the other’s was as black as a crow’s wing.

‘Look!’ Eric pointed up at the three cats.

The older woman uttered a throaty snarl. ‘What are they doing here? I’ve forbidden them, expressly.’

The younger woman, Eric’s stepmother, grabbed his hand and dragged him back. ‘I’ve told you never to approach those creatures.’

‘I didn’t,’ said Eric. ‘I’m down here and they’re up there. And anyway, they can’t hurt me.’

‘Of course they can,’ his stepmother retorted. ‘They’re wild creatures.’

‘With leopards’ hearts,’ her sister added. Raising her voice, she called, ‘Charlie! Charlie Bone, come here, this minute.’

A door opened upstairs and a moment later a boy with tousled hair leaned over the railing. The yellow cat walked up to him and rubbed its head against his arm. The other cats jumped down and circled his legs.

‘What is it, Grandma?’ Charlie stroked the yellow cat’s head and yawned.

‘Lazy lump!’ said his grandmother. ‘Have you been asleep?’

‘No,’ Charlie replied indignantly. ‘I’ve been doing my homework.’

‘Did you let those cats in?’

‘They’re not doing any harm,’ said Charlie.

‘Harm?’ Grandma Bone’s dark eyes became angry slits. ‘They’re the most harmful creatures in this city. Get them out.’

‘Sorry, Sagittarius.’ Charlie lifted the yellow cat off the banisters. ‘Sorry, Aries and Leo,’ he said to the cats winding themselves round his legs. ‘Grandma Bone says you’ve got to go.’

Whether it was Charlie’s tone of voice or his actual words was not clear, but the cats appeared to know exactly what he was saying. They followed him into his bedroom and, when he had opened his window, they jumped through it, one by one, on to the branch of a chestnut tree that stretched close to the sill.

‘See you at the Pets’ Café,’ Charlie called as the Flames leapt on to the pavement. They bounded up the street with a chorus of mews that made a dog, on the other side of the street, stop dead in its tracks.

Charlie smiled and closed the window. Returning to the landing, he found his grandmother, his great-aunt Venetia and Eric still staring up at him.

‘Have they gone?’ Grandma Bone demanded.

‘Yes, Grandma,’ Charlie said wearily.

At this point a third woman emerged from the sitting room. With her sharp features and abundant grey hair she was clearly related to the other two women. She was, in fact, Charlie’s great-aunt Eustacia. She was carrying a flat rectangular object covered in brown paper. It was about a metre and a half long and, perhaps, just under a metre wide.

Charlie knew there was no point in asking about the package. He would be told to mind his own business. But he had a fairly good idea what it was. He began to feel unaccountably excited.

‘What are you staring at?’ Great Aunt Eustacia grunted at Charlie.

‘Get back to your homework,’ ordered Grandma Bone.

Eric’s thin little mouth twisted into an unpleasant smirk. ‘Goodbye, Charlie Bone!’

Charlie didn’t bother to reply. He went back to his room and closed the door with a loud click. But then, as quietly as possible, he opened it, just a fraction. He wanted to know what was going to happen to the object Eustacia was carrying. Surely, it had to be a painting.

It was two years since Charlie had discovered his extraordinary endowment. It had begun when he heard voices coming from a photograph. Over the next few months Charlie found himself travelling into photographs and talking to people who had died many years before. When he turned his attention to paintings, the same thing had happened: he could meet the subjects in old paintings, people who had lived centuries before. Charlie often tried to avoid these situations; it was one thing to go into the past, quite another to leave it. Once or twice he’d been lucky to get out alive.

For some reason, the rectangular object with its covering of wrinkled brown paper aroused Charlie’s intense curiosity. He put his ear to the crack in the door and listened.

‘Why you’ve brought it here, I can’t imagine.’ Grandma’s voice crackled with irritation.

‘I told you,’ whined Great Aunt Eustacia, ‘my basement’s damp.’

‘Hang it on your wall, then.’

‘I don’t like it.’

‘Then give it to –’

‘Don’t look at me,’ said Great Aunt Venetia. ‘It gives me the creeps.’

‘She made me take it,’ Eustacia said fretfully. ‘Mrs Tilpin isn’t someone you can argue with.’

Charlie stiffened. He hadn’t heard Mrs Tilpin’s name mentioned for some time. Once, she had been a rather pretty music teacher called Miss Chrystal, but she hadn’t been seen since she had been revealed as a witch.

‘They won’t keep it at the school,’ went on Eustacia. ‘Even Ezekiel is wary of it. He says it steals his thoughts, it draws them away like a magnet – he says.’

‘Joshua Tilpin is a magnet,’ said Eric.

His stepmother uttered a short, dry laugh. ‘Huh! The witch’s son. So he is.’

At this everyone began to talk at once, and Charlie had difficulty in making out what was said, but it seemed that Grandma Bone had finally agreed to allow the painting, or whatever it was, to be stored in her cellar. Strictly speaking, it wasn’t her cellar, because she shared the house with her brother, Paton. Charlie and his other grandmother, Maisie, had been permitted to live there until Charlie’s parents returned from their second honeymoon, and their house, ‘Diamond Corner’, had been restored.

There began a succession of bangs, scrapings and irritated exclamations as the painting was presumably carried down into the cellar. Finally, the cellar door was shut and, after more discussions, bangs and clicks, Grandma Bone, her two sisters and Eric left the house.

Charlie waited in his room until he heard everyone bundle into Great Aunt Eustacia’s car. Then, with much mis-firing and a painful scraping of gears, the old Ford lurched down the street.

After another five minutes had passed, Charlie slipped out of his room and ran downstairs. When he reached the cellar he found that the door had been locked. Luckily, Charlie knew where all the keys were kept. He went into the kitchen and pulled a chair up to the dresser. Standing on tiptoe, he reached for a large blue jug patterned with golden fishes.

‘And what might you be up to?’ said a voice.

Charlie hesitated. The chair wobbled. Charlie uttered a shaky yelp and steadied himself. He hadn’t noticed Grandma Maisie folding the washing in a corner.

‘Maisie, are you spying on me?’ asked Charlie.

Maisie straightened up. ‘I’ve got better things to do, young man.’

Charlie’s other grandmother was the very opposite of Grandma Bone. Maisie wasn’t much taller than Charlie and battled hard to keep her weight down. Being the family cook didn’t make this easy.

‘Now, I wonder why you were trying to get those keys?’ Maisie’s face was too round and cheerful to look stern. Even frowning was an effort. ‘Don’t deny it. There’s nothing else up there that would interest you.’

‘I think Great Aunt Eustacia has put a painting in the cellar.’

‘What if she has?’

‘I . . . well, I just wanted to . . . you know, have a look at it.’ Charlie clutched the fish jug and drew out a large, rusty-looking key.

Maisie shook her head. ‘Not a good idea, Charlie.’

‘Why?’ Charlie replaced the jug and jumped down from the chair.

‘You know them,’ said Maisie with meaning. ‘Those Yewbeam sisters are always trying to trick you. D’you think they didn’t know you’d be just itching to take a look at . . . whatever it is?’

‘They didn’t know I was listening, Maisie.’

‘Huh!’ Maisie grunted. ‘Course they did.’

Charlie twiddled the key between his fingers. ‘I just want to take a look at the outside of it, the shape of it. I won’t take the paper off.’

‘Oh no? Look, Charlie, your parents are watching whales on the other side of the world. If something happens to you, how am I going to . . .?’

‘Nothing will happen to me.’ Before Maisie could say another word, Charlie walked briskly out of the kitchen and along the passage to the cellar. The key turned in the lock with surprising ease. But as soon as the low door opened, Charlie knew that there was really no doubt – something would happen to him. He could feel it already: a light, insistent tug, drawing him closer; down a set of creaking wooden steps, down, down, down, until he stood in the chilly gloom of the cellar.

The package was propped against the wall, between an old mattress and a set of rusty curtain poles. Charlie couldn’t be certain but he thought he could hear a faint sound coming from beneath the crumpled wrapping paper.

‘Impossible!’ Charlie clutched his hair. This had never happened before. He had to see a face before he heard its voice. But this sound was coming from something out of sight. As he stepped towards the package a deep whine whistled past his ears.

‘Wind?’ Charlie reached out a hand.

At his touch the paper rustled and creaked. The whole package seemed suddenly alive and Charlie hesitated. But a second of doubt was immediately overcome by his burning curiosity, and he began to tear at the wrapping. Strips of paper flew into the air, borne by Charlie’s frantic fingers and the unnatural wind that blew from who knew where.

The painting didn’t even wait to be entirely revealed. Long before every corner was free of the paper, a dreadful landscape began to seep into the dim cellar. This was not how it should happen. Charlie was mystified. He waited for the familiar tumbling sensation that usually overwhelmed him when he travelled into paintings. It never came. He watched in astonishment as the brick walls of the cellar were swallowed by a vista of distant mountains. Tall, dark towers appeared in the foreground; one swam so close to Charlie that he could smell the damp moss that patched the walls. Ugly scaled creatures scuttled over the surface, pausing briefly to stare at Charlie with dangerous glinting eyes.

It has to be an illusion, Charlie told himself. He put out his hand – and touched the horny spine of a black toad-like thing. ‘Ugh!’ Leaping away from it, he tripped and fell on to his back. Beneath him he could feel rough stone cobbles, slippery with grey-black weeds. Above him purple clouds rushed through an ash-coloured sky, and all about him the wind roared and rattled, howled and sighed.

‘So I’m there already.’ Charlie got to his feet and rubbed his back. ‘Wherever there is.’

In brief intervals, when the wind died to a low whine, Charlie could hear the tramp of heavy feet and a low muttering of voices. ‘It’s here,’ one said. ‘I can smell it.’

‘It’s mine.’ This voice glooped like a sink full of dishes. ‘I know how to catch it.’

‘Oddthumb knows,’ came a chorus of low, tuneless voices.

Charlie backed round the tower as the marching feet drew closer. There appeared to be no windows in the building and Charlie was just beginning to think that it was without a door, when he was suddenly seized round the waist and lifted high in the air. A huge fist closed over his mouth and a voice, close to his ear, whispered, ‘Boy, your life depends on your silence.’

Shocked and speechless, Charlie was swung backwards through an open door and set down. He found himself on the lowest step of a stone staircase that spiralled upwards before disappearing into the shadows.

‘Climb,’ whispered the voice, ‘as fast as your feet will take you.’

Charlie mounted the stone steps, his heart beating wildly. Up, up and up, never stopping until he had reached a door at the very top. Charlie pushed it open and went into the room beyond. A narrow window high in the wall shed a dismal light on to the sparse furnishings beneath: the longest bed Charlie had ever seen, the highest table and the tallest chair, and . . . could that be a boat, hanging on the wall? He turned quickly as the owner of the room ducked under the lintel and walked in, closing the door and locking it.

Charlie beheld a giant, or the nearest thing to a giant he had ever seen. The man’s white hair was coiled into a knob at the back of his head, and a fine, snowy beard reached a neat point just above his waist. He wore a coarse shirt, a leather waistcoat and brown woollen trousers tied at the ankle with cord.

The giant held a finger to his lips and then, raising his arm, pushed open a small panel set between the rafters of the roof. Without a word, he lifted Charlie up to the dark space revealed. Charlie rolled sideways and the panel was immediately replaced, leaving him in a dark, stuffy hole with his knees drawn up to his chest and his arms wrapped around his legs.

‘They’ll not find you. Trust me,’ whispered the giant, whose head was perhaps only a foot below the rafters.

There was a tiny hole right beside Charlie’s ear and when he turned his head, he could see directly into the room below. He had just positioned himself as comfortably as possible when he heard voices echoing up the stairwell.

‘Otus Yewbeam, are you there?’

‘Have you seen the boy?’

‘Caught him, have you?’

‘He’s ours.’

‘Mine,’ came Oddthumb’s husky snarl. ‘All mine.’

A battery of fists and cudgels began to thump against the door.

‘Patience, soldiers,’ called Otus. ‘I was sleeping.’ One step took him to the door, which he unlocked, with much sighing and rattling.

A crowd of squat, ugly beings rushed in and surrounded the giant. They wore metal breast-plates over their patched leather jerkins, and strapped to their heads were tall helmets like metal top hats. Axes, knives, catapults and cudgels hung from their belts, though some had bows slung over their backs, and quivers bursting with shiny arrows. Most came well below the giant’s waist, but there was one, somewhat larger than the others, who looked familiar to Charlie. Couldn’t be the same carved stone troll that had once sat outside Great Aunt Venetia’s gloomy house?

‘Why did you lock the door against us?’ this larger being demanded.

‘Not against you, Oddthumb,’ said the giant, ‘against durgles.’

‘Durgles!’ spat Oddthumb.

‘Durgles are very destructive,’ said Otus. ‘Many a day they have eaten my bread whilst I slept.’

‘Liar,’ said Oddthumb. ‘A durgle can no more unlock a door than a diddycock. You have got him, I know it.’

‘Who?’ Otus enquired in a mild tone.

‘The boy,’ snarled one of the smaller beings. ‘He’s here. The Watch see’d him a’coming from far off. Caught he was, by the Count’s guile.’

‘Enchanted,’ said the being beside him.

‘Spell-brought,’ chorused the others.

There was a loud creak as Otus lowered himself on to his bed. He was now out of Charlie’s sight, though he could still see a long leather-bound foot.

‘Respected soldiers, I have seen no boy,’ said Otus. ‘Search this room if you must.’

‘We will,’ grunted Oddthumb. ‘Up, giant!’

Otus had barely risen from the bed, when Oddthumb and his crew had pushed it over. They slashed at the blankets, battered the straw mattress, tore off a cupboard door, turned over a thin rush mat, poked up the chimney, pulled charred wood from the fire, and hacked at the floorboards. The frenzied attack lasted no more than ten minutes and, from his hiding place, Charlie saw a growing pile of ash and straw, broken pottery and chunks of bread.

‘Squirras!’ cried one of the soldiers suddenly.

Charlie couldn’t see what he had found. It must have been on the far side of the room.

‘Greedy, greedy,’ said Oddthumb. ‘Six squirras for your brekfass, Otus?’

‘I’m a giant,’ sighed Otus.

‘We’ll leave one – the smallest,’ Oddthumb said spitefully.

‘I thank you,’ said Otus.

A soldier with a warty face came and stood directly under Charlie’s spyhole. ‘No boy here, General,’ he said. ‘In forest maybe?’

‘No boy, eh? No boy.’ Oddthumb paced across the room. He stopped beside Wart-face and looked up.

Charlie found himself staring into a stoney grey eye. He dared not blink. He dared not breathe. His own eye began to ache as he held it wide open and unmoving. Could Oddthumb see him? Did he sense Charlie’s presence, lying above? An urge to sneeze overcame Charlie. He pressed his lips together, brought his fingers slowly up to his face and clamped them over his nose.

‘Dreaded creatures up there,’ whispered Wart-face. ‘Blancavamps maybe. Let us leave here, General.’

‘Blancavamps?’ Oddthumb stroked his chin with a grotesque thumb, as big as his hand. ‘Have you got blancavamps, Otus?’

Charlie had difficulty in stifling a gasp.

‘Sadly,’ said the giant. ‘They steal my sleep.’

Oddthumb threw back his head and gave a hideous burbling chuckle. In a second the room was filled with gurgling laughter, as the soldiers echoed their general. The dreadful sound stopped abruptly the moment Oddthumb closed his mouth. Without another word, the general marched out, followed by his troops.

Charlie listened to the stamp of heavy feet receding down the steps. A door at the foot of the tower clanged shut and the soldiers began to march down the street. Charlie waited breathlessly. He dared not move for fear one of the soldiers remained in the room below. He could hear Otus settling his room to rights after the rough intrusion.

Long after the footsteps had faded, the giant came and grinned up at Charlie. ‘You are safe, boy. Be not afeared, I will get you down.’

‘Thanks,’ Charlie said huskily.

The giant pushed back the panel, saying, ‘Step on to my shoulders.’ He held up his arms and Charlie thrust his legs through the hole. Otus gently lifted him down and set him on the bed.

Charlie wriggled his aching shoulders and rubbed his arms. ‘I’m not sure how I got here,’ he said.

The giant pulled his chair up to the bed and sat down. Putting his head on one side, he regarded Charlie quizzically. ‘Your name?’ he asked.

‘Charlie Bone, sir.’

‘You are a traveller?’

‘I . . . yes, I am sometimes. I can travel into photos and paintings.’ Observing the giant’s puzzled frown, Charlie added quickly, ‘Photos are a bit difficult to explain, but I expect you know what a painting is.’ The giant nodded. ‘Anyhow, this time it was different, my travelling, I mean. This time a painting has . . . kind of . . . captured me.’

‘Mm.’ The giant nodded again. ‘My wife had a mirror that took her a-travelling.’

‘A mirror?’ Charlie said excitedly. ‘My ancestor, Amoret, had a mirror. It caused a bit of trouble. Someone wanted it . . . an enchanter.’

‘Amoret was my wife!’ The giant clutched Charlie’s hand in his huge fist. ‘My name is Otus Yewbeam.’

‘Then . . . you’re my ancestor, too.’ Charlie’s gaze slid over the giant’s long frame, from the crown of his head to the tip of his long foot. ‘Maybe I’ll grow a bit.’

The giant smiled. ‘I was this high when I was a boy.’ He held his hand about six feet from the ground.

‘Oh,’ said Charlie, a little sadly.

‘What is your century?’ asked Otus.

‘Um . . . twenty-first,’ said Charlie, after a bit of thought.

‘There are nine hundred years between us.’

Charlie frowned. ‘I don’t get it. I’ve never, ever come into the past this way. I was just looking at a painting; I saw mountains and towers, but no people, and then, suddenly, it was all around me.’

‘He is powerful,’ Otus said gravely. ‘He wanted you in Badlock.’

‘Who?’

‘Count, enchanter, shadow of Badlock; he has many names. He brought me here as a captive, twenty years ago, when my wife fled to her brother’s castle.’ The giant’s large eyes clouded for a moment, and he looked up at the fading light in the window. ‘He wanted Amoret. He wanted all the Red King’s children. Five he won easily, they already walked the path of wickedness. The others – Amadis, Amoret, Guanhamara, Petrello and Tolemeo – they fled the evil. It was Tolemeo who rescued my son, Roland, and for that the shadow punished me. His soldiers relish torture. Now they let me bide in peace. I am forgotten, almost.’

Charlie reminded the giant that, today, the soldiers had not let him bide in peace. ‘I’ve put you in danger,’ he said. ‘If they catch me . . .?’

‘No,’ the giant leaned forward earnestly. ‘They will not catch you.’ He got up and strode over to a hearth set into a wide chimney breast. ‘Presently, we shall dine on squirra, boy.’

‘Oh, good.’ A note of anxiety crept into Charlie’s voice. What was a squirra, he wondered.

The giant opened a small door in the wall and brought out a black rat-like creature with an extremely long, hairless tail. ‘Only one,’ Otus sighed. ‘But it will suffice.’

Charlie’s stomach lurched. ‘If that’s a squirra, what’s a blancavamp?’

Otus chuckled. ‘They are what we, in our world, know as bats, but blancavamps are white as snow. The people of Badlock believe them to be ghosts. But I am not afeared of them.’

‘Nor me.’ Charlie darted a quick look in the giant’s direction. Otus was already skinning the squirra and, hoping it was something he would never need to do, Charlie looked quickly away. ‘Have you ever tried to get home again?’ he asked the giant.

Otus gave a rueful smile. ‘My wife’s brother, Tolemeo, tried a second time to rescue me, but Oddthumb and his ruffians caught us. Tolemeo was lucky to escape with his life. And, knowing my wife had perished, I cared less and less how and where my life should end.’

Charlie recalled the fleeting image of a beautiful woman smiling out from a mirrored wall, and a near-impossible plan began to take shape in his mind.

‘Badlock is a country no one from our world can find,’ the giant continued. ‘No one but clever Tolemeo. It is an awful place. There is the eternal wind, and then, in winter, there is a deluge. Water fills the land between the mountains, a fathom deep.’

‘It is a boat, then.’ Charlie nodded at the wooden boat-shape hanging on the wall.

‘Indeed, a boat. There is no other place to live but in a tower.’

‘And where does the Enchanter live?’

‘In a dark fortress, a scar on the mountain. I’ll show you.’ Dropping the meat into an iron pot, Otus wiped his hands on a rag tucked into his belt and, before Charlie could protest, lifted him up to the high window.

Night was falling fast, but the mountains were sharply outlined against a ribbon of pale green sky. Close to the top of the tallest mountain, flickering red lights could be seen and, behind them, a black shape capped with steep turrets.

‘He is seldom there,’ said the giant, ‘but the fires burn constantly to remind his subjects that he is watching them.’

Charlie shuddered. It had only just occurred to him that he might be trapped in this hostile world forever. He was about to be lowered to the ground when he shouted, ‘Stop. I see something.’

A few feet away from the base of the giant’s tower stood a large yellow dog. It was staring up at the window. When the dog caught Charlie’s eye, it began to bark.

‘Runner Bean!’ cried Charlie.

How had his best friend’s dog followed him into a painting? It couldn’t happen.

But it had.