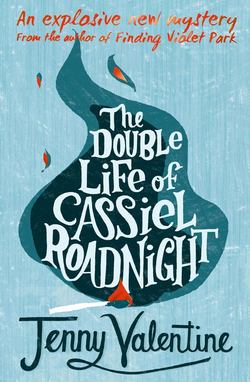

Читать книгу The Double Life of Cassiel Roadnight - Jenny Valentine - Страница 10

FIVE

ОглавлениеNow and again I persuaded Grandad that we needed to go out – to the city farm maybe, or the market, or along the canal. He never saw the point. I think after years of hiding in the dust-yellow insides of his books, real life was like roping lead weights to his feet and jumping into cold water; just not something he felt like doing.

He didn’t mind me going out on my own. He said it was a good idea.

He said, “The namby-pamby children of today have no knowledge of danger and no sense of direction.”

He said, “When I was your age I was out for days at a time with nothing but a compass and a piece of string.”

He said he very much doubted I’d get lost or stolen, or fall down a manhole.

He was right. I didn’t.

Still, sometimes I persuaded him to get dressed and come with me, just because I liked him being there, just because he needed the fresh air. His skin was lightless, and thin like paper. His hair was like a burnt cloud. I told him if he didn’t get out in the sunshine once in a while he might turn into a page from one of his mildewed books, and the slightest gust of wind would blow him to nothing. I sort of believed it.

Out on my own I was quick and agile. I could walk on walls and weave through crowds and duck under bridges and squeeze into tiny spaces and jump over gates. Grandad wasn’t so good at walking. He tripped over a lot and staggered sometimes, and forgot where he was going. Once he fell into the canal. Not fell exactly – he was too close to the edge and he walked right into it, like it was what he’d been meaning to do all along. He was wearing a big sheepskin coat and it got all heavy with water and he couldn’t get up again. It wasn’t deep, it wasn’t dangerous. It was funny. He stood there with the filthy water up to his chest, soaking into his coat, changing the colour of it from sand to black.

“Come on in,” he said to me. “The water’s lovely.”

“No thanks, Grandad,” I said.

He winked at me. “This reminds me,” he said, trying to heave himself up off the bottom, “of my childhood holidays on the French Riviera.”

I think the coat weighed more than he did. He took it off in the end and waded out in his thin suit, like a wet dog. The coat lay there on the water, like a man face down with his arms stretched out on either side, looking for something on the canal floor, quietly drowning. We had to rescue it with a stick.

“I never liked this coat,” Grandad said as we walked back the way we’d come, carrying it between us like a body, straight back to the house. His teeth banged together when he talked, like an old skeleton. Water ran off him like a wet tent. His shoes were ruined. There were leaves in his hair, leaves and rat shit.

We laughed and laughed.

I didn’t know Grandad was drunk then. It never occurred to me. I don’t think I knew what drunk was. When you’re a kid you fall over and bang into things all the time. I didn’t realise you were supposed to grow out of it.

I wouldn’t have minded anyway. If you ask me, Grandad drunk wasn’t any worse than Grandad sober. Not when you love a person that much. Not when a person is all you’ve got.

I only saw Grandad cry one time and he hadn’t been drinking. He hadn’t been allowed to. It was after the accident, when I went to see him, just that once.

He was so pale, so almost lifeless I thought he was disappearing.

He tried to talk to me. He tried to tell me the truth, and his tears kept getting in the way of the words. Great racking sobs tore through his voice.

I didn’t hold him like I held Edie. I was too shocked.

I should have held him like I held her. I should have done it, but I didn’t.