Читать книгу Taming the Flood: Rivers, Wetlands and the Centuries-Old Battle Against Flooding - Jeremy Purseglove - Страница 19

THE COURTS OF SEWERS

ОглавлениеSuch piecemeal, not to mention conflicting, management of the marshes was no way to organize and control the ever-threatening flood-waters; and from the mid-thirteenth century, the responsibility for land drainage and reclamation from the sea began to devolve upon successive ‘commissions of sewers’, which were answerable to central government. A ‘sewer’ was a straight cut, the kind of geometrical channel beloved by modern engineers, and did not have the connotation of foul water which it has today. The first commission of sewers was set up in Lincolnshire by Henry de Bathe in 1258. Like fenland engineers 400 years later, de Bathe went for advice on procedure and administration to the heartland of organized land drainage, Romney Marsh. The subsequent courts of sewers were steadily reinforced by successive legislation, culminating in 1532 in Henry VIII’s Statute of Sewers, just at the moment when the power of the monastic lords of the levels was broken by the Reformation. These courts were to survive, incredibly, until 1930.

With the growth of commissions of sewers in the Middle Ages, the role of professional laypeople in such matters began to increase. In 1390 a commission was appointed to inspect and repair flood-banks and dykes on the Thames marshes between Greenwich and Woolwich. It included among its number the king’s clerk of works, no less than Geoffrey Chaucer.11 The last major drainage operation in the medieval period, however, was instigated by a churchman. John Morton, later to become Henry VII’s lord chancellor, familiar to every schoolchild for his tax levies of ‘Morton’s Fork’, organized the construction of the channel still known as Morton’s Leam, when he was bishop of Ely between 1478 and 1486. This ambitious piece of engineering, extending for 12 miles between Peterborough and Wisbech, survives today, although the tower Morton built from which to watch over his work-force crumbled away in the early nineteenth century.

By the end of the Middle Ages, the marshes in Kent and Sussex had been sufficiently reclaimed to reveal an abiding characteristic of such operations: that in certain circumstances land drainage contains the seeds of its own destruction. In the mid-fifteenth century, floods and silting doomed the old port of Pevensey; and further along the coast, on Romney Marsh, a series of catastrophic storms culminating in 1287 obliterated the towns of Old Winchelsea and Broomhill. Although climatic deterioration in the later Middle Ages certainly worsened the situation, these disasters were not simply the haphazard expression of hostile Nature. They were made inevitable by human meddling. At Pevensey, reclamation of the adjacent estuary reduced tidal scouring, which had previously kept the river mouth open. In consequence, the water, unable to escape through the blocked outfall, flooded the land, and navigation up the river was also prevented. Successive new channels cut in 1402 and 1455 failed to remedy the problem, and Pevensey Castle, which still rises dramatically above the marshes whose creation ensured its demise, was abandoned.12 On Romney Marsh, silting of river mouths was worsened by the problem of peat shrinkage. By the twelfth century, increasingly elaborate drainage schemes had led to contraction of the peat, thereby causing the land to drop ever lower in relation to the menacing waters of the English Channel. When the banks finally broke, the sea captured both arms of the river Rother, and created the present estuary south of Rye. This cat-and-mouse game between engineers and the elements was to become a major theme in the next great age of wetland reclamation, which began under the Tudors and reached its climax in the middle of the seventeenth century.

Following the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, the flood-waters began to rise again, since there were no monks to operate the sluices and dig the drains. At least, this was the opinion of Dugdale, writing a hundred years later; but it should be remembered that he was one of a long line of propagandists for land drainage, and that, while localized deterioration must have taken place, there is also ample evidence of the activities of the courts of sewers and of individual enterprise by secular landlords. In 1539 the gentry around Newhaven diverted the Sussex Ouse to improve the drainage of the estuarine marshland and to capture navigation and trade from their neighbours at Seaford. During the reign of Elizabeth, the Wealdmoors in Shropshire were a battleground between rival landlords intent on drainage and enclosure. In 1576 Thomas Cherrington complained in the Queen’s Council of the Marches, that Thurston Woodcock, lord of Meason, had assembled a gang armed with long staffs and billhooks, and had forcibly ploughed and then enclosed a piece of his waste ground with a ditch. Clearly Cherrington was not above such tactics either, for he seems to have destroyed the ditch. In 1583 the Woodcocks were back ‘with divers … desperate and lewde persons’ who ‘in riotous manner dug … one myghty diche more like in truthe a defence to have kepte owte some forren enemyes than an inclosure to keepe in cattell’.13

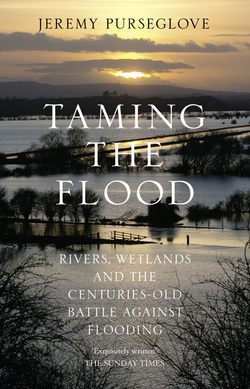

Romney Marsh.