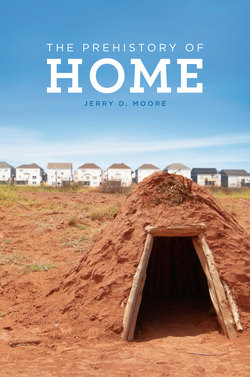

Читать книгу The Prehistory of Home - Jerry D. Moore - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

Mobile Homes

Let us never lose sight of our little rustic hut.

—Marc-Antoine Laugier, An Essay on Architecture

The portaledge is a collapsible platform of tubing and rip-stop nylon that big-wall rock climbers use when a prolonged ascent requires spending nights out on a sheer rock face. First designed in the 1980s, the portaledge allows climbers to make multi-day ascents of big walls in regions with severe weather. It extends the climbers’ reach.1

The platform is just large enough for two climbers to sleep in. A web of nylon lines binds the portaledge to a central anchor point, such as a pair of expansion bolts drilled into solid rock. A separate protection point is placed away from the portaledge; other gear is snapped into this anchor especially metal carabineers, chock nuts, or ice axes that might attract lightening bolts. A small bucket dangles from a tent pole, supporting a tiny stove for heat and cooking. Covered with a durable tent designed to both shed moisture and allow air circulation, the portaledge is a secure, though improbable, refuge in a storm.

Few humans occupy such perilous environments as the vertical granite massif of El Capitan in the Yosemite Valley or the sheer red cliffs of Zion National Park. But just as the portaledge allows climbers a sheltered night’s rest as they dangle hundreds of feet in the air, humans use dwellings to extend their reach even for just a night or a few days. And we have done so for more than seven hundred thousand years.

. . .

FIGURE 3. J. Middendorf, The Portaledge, circa 1990. Drawing courtesy of John Middendorf.

The most influential American archaeologist of his generation, Lewis Binford (1931–2011) spent decades carefully examining ethnographic accounts of traditional cultures and searching for patterns in human behavior that would be discernible in the archaeological record. Explicitly committed to the scientific search for law-like generalizations, Bin-ford compiled massive data sets based on literally hundreds of case studies about historic and modern hunting and gathering societies. While those hunting and gathering societies are not static representatives of earlier Paleolithic people, the case studies suggested some basic patterns relevant to thinking about the past. Although Binford’s studies ranged over different aspects of the lives of hunters and gatherers, one analysis explored the question: Why do hunters and gatherers build such different kinds of homes?2

One of the first conclusions from Binford’s study is simultaneously surprising and obvious: All hunters and gatherers build shelters, even at camps they occupy for a single night. This would be an uninteresting conclusion, were it not for the long-standing, Western assumptions about the rootless, au naturel existence of hunters and gatherers.

As the eighteenth-century thinker Giambattista Vico succinctly observed, “This was the order of human institutions: first the forests, after that the huts, then the villages, next the cities, and finally the academies.”3 In Vico’s reconstruction, the earliest wild and sylvan stage occurred in the aftermath of the Great Flood, “when the impious races of the three children of Noah, having lapsed into a state of bestiality, went wandering like wild beasts until they were scattered and dispersed through the great forest of the earth.”4

Similar musings form a recurrent theme in Western thought about human origins. During the first century B.C., the Roman architect Vitruvius considered the origins of the earliest buildings in his classic Ten Books of Architecture. Humans came together, Vitruvius proposed, when attracted by the unusual warmth of lightening-struck trees. Since they were bipedal,

having from nature this boon beyond other animals, that they should walk, not with the head down, but upright, and should look upon the magnificence of the world and of the stars.

They also easily handled with their hands and fingers whatever they wished. Hence after thus meeting together, they began, some to make shelters of leaves, some to dig caves under the hills, some to make of mud and wattles places for shelter, imitating the nests of swallows and their methods of building. Then observing the houses of others and adding to their ideas new things from day to day, they produced better kinds of huts.5

The homelessness of savage nations is a theme touched on by different writers, not surprisingly by Enlightenment authors discussing the origins of architecture. In his 1791 “A Treatise on the Decorative Part of Civil Architecture,” the British Neoclassical architect Sir William Chambers imagined a Paleolithic idyll, in which “every grove afforded shade from the rays of the sun, and shelter from the dews of the night” and our ancient forebears “fed upon the spontaneous productions of the soil, and lived without care, as without labor.”6

Chambers’s model of human origins combined an Enlightenment version of selective pressures with a Stone Age precursor of Hedonism II. The seductive tropical climate inevitably led to procreation, and as population increased, competition intensified for scarce resources. Consequently, Chambers opined, “separation became necessary; and colonies dispersed to different regions: where frequent rain, storms and piercing cold, forced the inhabitants to seek for better shelter than trees.” The tropical emigrants “at first… most likely retired to caverns… but soon disgusted with the damp and darkness of these habitations, they began to search after more wholesome and comfortable dwellings.”

FIGURE 4. “The First Building.” After Viollet-le-Druc.

Binford’s analysis is a relief after these florid musings. He argued that the shelters hunters and gatherers build—and remember, they all build shelters—reflect, in part, their broader adaptations to physical environments, whether they live in the equatorial tropics or arctic tundra. First, hunters and gatherers vary in their mobility. Fully nomadic groups move camps throughout the year, while seminomadic hunters often construct a substantial dwelling each winter, but spread out to seasonal camps when the weather is less severe. Semisedentary hunters and gatherers construct residences that they regularly reoccupy, although venturing out from those hubs and constructing temporary shelters before returning home. Sedentary hunters occupy dwellings year-round, although hunting parties or foraging groups may journey out to find key resources and bring them back home.

TABLE 1 MOBILITY AND HOUSE PLAN IN HUNTING AND GATHERING SOCIETIES

Second, mobility shapes the form and construction of hunter-gatherer houses. More nomadic groups build circular or semicircular dwellings. More sedentary groups build rectangular houses. More nomadic groups either transport the building materials—for example, the canvas and poles of a tent—or they build their homes from immediately available materials. More sedentary hunters and gatherers will transport construction materials to the house site, often building the roof and walls of different materials, which more mobile hunters and gatherers do not. Seminomadic and semisedentary groups often have different types of dwellings lived in during different seasons or by different groups of people, while the most mobile and the most sedentary groups tend to occupy only one kind of dwelling, whether impermanent or enduring.

Third, such variations are shaped by the specific demands of subsistence. When a people’s diet is based on hunted game, they tend to move more frequently, occupying circular or semicircular dwellings built from locally available or transported materials—especially if they have dogs, horses, or caribou that can carry tents and poles. When a people’s diet is based on fish, mollusks, or marine mammals, they tend to be less mobile, living in more permanent and substantial dwellings.

Binford’s insights imply that the earliest forms of mobile homes reflect the calculations of survival. We have to consider the dwelling within a complex framework of other decisions—about food-getting and movement—that hunter-gatherers make in order to survive. Rather than the blind clawings away from beastliness as the Enlightenment thinkers had suggested, such little rustic huts reflect a rationality that those savants would have prized.

. . .

On the Pacific Coast of Baja California, powerful waves chisel away at the coastal terrace. The coastal terrace consists of uplifted marine sediments, ancient shorelines raised as the Earth’s tectonic plates groaned and buckled. The soils are an unconsolidated jumble of wave-rolled cobbles, clays, and silts. In deep, ancient times when glaciers melted and sea levels rose, the Pacific Ocean cut a long escarpment that runs for 150 kilometers, still visible 130,000 years later. A handful of brief rivers and numerous small arroyos cut through the coastal terrace in search of the sea.

Arroyo Hondo forms a large and (as the name suggests) deep drainage that slices a convoluted landscape whose names portray the difficulties of travel by Catholic missionaries and Mexican soldiers. Almost two hundred years after sea voyagers claimed the Californias for Spain, the colonization of Baja California was a slow and painful process in a landscape of agony. Even when translated into English, the place-names reflect this. Viper Pass. Arroyo of the Martyrs. The Sacrifice.

The Native American experience of this same place was profoundly different. Traveling over the cactus-spiked mesas between the warm waters of the Gulf of California and the cold waves of the Pacific Ocean, small bands of Kiliwa and Cochimi sought food, raised children, and told legends of the making of the land. The legends recounted how Menchipa, the gigantic original deity, created freshwater springs with the tip of his walking staff as he strode across the world. Each night the three Mountain Sheep stars, known to Europeans as the stellar trio in Orion’s belt, galloped across the peninsula in the luminous night sky.

Few Europeans perceived this order, the way landscape and movement could result in the creation of home. One Jesuit missionary, the German priest John Jakob Baegert, described the natives as Naturvoelklein who “by no means represented communities of rational beings, … but resembled nothing less than a herd of swine, each of which runs around grunting as it likes, together today and scattered tomorrow till they meet again by accident at some future time.”7 Another Jesuit, the usually informative observer Miguel del Barco, said of the generally naked natives, “The house and dwelling of the Californians are no better nor comfortable than their costumes and dresses.”8 A Mexican Jesuit who spent the late eighteenth century in northern Baja California lamented the general disorder of indigenous society: “They have no government nor do they recognize a king … but only some captain and as they possess no titles to land, no houses, no real estate, nor have any sort of towns, … the need to find food prevents them from establishing themselves in fixed places.”9 What these Europeans failed to see was the stability of movement, a durably flexible response that is evident in the archaeology of Baja California.

Since the early 1990s, I have conducted archaeological research in the San Quintín–El Rosario region, on the Pacific coast about two hundred miles south of the U.S. -Mexico border. My students and I have recorded hundreds of sites.10 The oldest known site dates to 5890–5660 B.C., and a handful of other sites are from the first half of the sixth millennium B.C. Since older sites have been discovered to the north and south, I assume that people moved through the region even earlier. Presumably, these older sites were eroded away or flooded as glacial sheets melted and sea levels rose to modern heights after the Pleistocene.

But after about 5500 B.C., we have dated enough archaeological sites to suggest how people made this landscape into home. First, just as the Jesuits had observed, there were no towns or cities: sites are relatively small open-air camps, most probably inhabited for a single season. There are no traces of permanent houses or other structures, and dwellings were probably brush windbreaks. Second, people seem to have followed the same basic pursuits: they made stone tools, collected shellfish from sandy beaches and rocky coastlines, hunted deer with spear-throwers and darts, and gathered agaves, trimming away the barbed leaves and roasting the agave hearts. Third, the prehistoric foragers lived in the region only part of the year. Most of their sites are kilometers away from permanent springs and rivers, suggesting that people camped in the area when temporary water sources were available during the wet winter months. And this basic pattern of seasonal, short-term encampments along the coast seems to have been followed for nearly seven thousand years.

In 1996 my students and I mapped a small site on the north bank of Arroyo Hondo. Stretching over three hundred meters, the site consisted of several discrete clusters of the debris of prehistoric daily life. The clusters formed two groups, probably reflecting two or more encampments by different bands of hunters and gatherers. Bright white shells of mussels, clams, and abalones glinted among the chaparral, but they too formed clusters of species: mussels and abalones from rocky coasts, Pismo clams from open sandy beaches, and Pacific littleneck clams from quieter, protected waters. Each cluster of mollusks represented a separate collecting trip to the seashore, a distance of three kilometers or more, and then the return to the sheltered campsite at Arroyo Hondo.

Other features and objects were evidence of ancient lives. A circular platform of fire-cracked rock was the base of a hearth where agave had been roasted. Two concentrations of dark grey basalt cores, hammer-stones, and flakes were temporary workshops where stone tools were made. And sprinkled across the site were eighteen metates, flat-topped cobble grinding slabs, and a half dozen manos, fist-sized cobblestone tools rubbed back and forth to pulverize and mill hard seeds or dried meat on the metates. Because the metates are heavy stone slabs, they were not carried from place to place but simply cached under a bush until the band returned. And this was the case at Arroyo Hondo: there were two piles of cached metates, stored under sagebrush in anticipation of return.

In contrast to the Jesuits’ biases, the native occupants of Arroyo Hondo were anything but a disorganized horde, desperately roaming the landscape in search of something to eat. The site at Arroyo Hondo clearly demonstrated planning, forethought, and order. The anthropologist Michael Jackson, who lived with mobile Aboriginal peoples in Australia, has written of “the Eurocentric bias to see all human experience from the perspective of the sedentary cultivator or householder…. In the West we have a habit of thinking of home as a house. Walls make us feel secure. Individual rooms give us a sense of privacy. We tend to believe that living in a house is synonymous with being civilized.”11

But, in fact, even when hunters and gatherers make brief encampments, they clear brush, build windbreaks, light fires, and cook food. They make home.

. . .

One of the defining qualities of modern human behavior is the way we organize the places where we live. In early hominid sites, there is a jumble of activities; flakes, cut bones, and hearths are intermixed. However, with the emergence of Homo sapiens there is a greater tendency to spatial order.

For example, in Kebara Cave, located in Israel on the western escarpment of Mt. Carmel and overlooking the eastern Mediterranean Sea, excavations in the 1980s uncovered a complex record of place-making by Neanderthals.12 Archaeologists had excavated different portions of Kebara Cave since the 1930s, and by the late 1950s the Middle Paleolithic antiquity of the site was recognized (see chapter 4). The excavations in the 1980s brought together a team of different specialists to examine Kebara Cave from multiple perspectives. In addition to detailed information on tool-making and faunal remains (such as gazelle, boar, horse, and deer among others), the Kebara Cave excavations uncovered evidence for the creation of spatial order. From the back wall of the cave, the archaeological deposits extended out some 33 meters to a small terrace past the cave’s drip-line, and Kebara Cave’s complex, inter-fingered stratigraphy in places was nearly 9 meters deep. The earliest levels contained numerous shallow oak-fueled hearths, particularly in the central portion of the cave. Elsewhere discrete concentrations of bones and stone flakes were uncovered, while the back wall of the cave was used as a garbage dump.

A Neanderthal burial was in the center of the cave at a depth of nearly 8 meters. A tall man in his late twenties or early thirties, the corpse had been laid in a shallow grave between 64,000 and 59,000 years ago. The skeleton was generally intact; it had not been scavenged by the hyenas that occasionally den in Kebara Cave. But there was a curious feature: the man’s skull was missing.

The lower jaw was present and an upper molar indicated that the Neanderthal man was not headless when he was put into the grave. The cranium had been removed after the ligaments connecting spine and skull had rotted away. The skull apparently was retrieved by other Neanderthals.

At later sites in the Levant, skull taking became common. In Late Natufian and Early Neolithic sites, skulls were removed and buried separately from the rest of the body, while in the Late Neolithic (ca. 9,400–7,600 years ago) skulls were sometimes removed from the corpse, covered with plaster, and decorated with cowry shells placed in the eye sockets.

But the headless corpse from Kebara was 50,000 years older than those manipulated skulls.

It is difficult to imagine what motivated the Neanderthal inhabitants of Kebara Cave. Was the head removed in an act of ancestor veneration or to defile the last remains of a hated enemy? It is impossible to know.

But we can know that the Neanderthal residents of Kebara Cave were making place, distinguishing cooking areas and tool-making spaces, differentiating the space of the living from the space of the dead. They exhibited this human propensity to create order at home.

This attention to domestic order even in simple dwellings is evidenced by the amazing discoveries at the site of Ohalo II in Israel. Dating to 23,000 years ago, Ohalo II is an open-air camp site on the edge of the Sea of Galilee. In the late 1980s water levels dropped 2–3 meters during a seven-year drought, and, as the lake waters receded, Ohalo II was exposed.

Because the site had been flooded soon after it was abandoned, the preservation of organic materials was extraordinary: charred seeds and fruits from more than one hundred plant species. Thousands of bone fragments—from gazelles, sixty species of waterfowl, and freshwater fish—indicated a year-round occupation that probably lasted no more than a few generations, a relative permanent settlement only abandoned when rising lake waters flooded the site.

In an area of 35 × 30 meters, archaeologists at Ohalo II uncovered the remains of six ancient huts interspersed with a half-dozen open-air hearth areas. The open-air hearth areas were large patches that had been burned at different times. Food debris and flint flakes clustered around the hearth areas. The huts were oval shelters built from branches of tamarisk, willow, and oak—quickly constructed dwellings, each 5–13 square meters in area. Sometime in antiquity, the huts had burned down, creating a dense layer of carbonized materials that preserved food remains and building materials.

The hut floors dipped slightly below the ground surface, and cross-sectioning excavations in Hut 1 exposed three different floors interspersed with thin layers of clays and sands. The meticulous excavations uncovered fascinating details of ancient life. People chipped flint tools inside the huts. Small clusters of tiny fish bones were from baskets of stored fish. But perhaps the most fascinating discoveries were the beds.

Three huts contained evidence of beds made from the stems of alkali grasses. The most complete bed was found in the lowest floor of Hut 1. Hut 1 had a central hearth surrounded by a layer of grass. Alkali grasses have soft and delicate stems, and the people of Ohalo II had harvested the grasses by cutting them off at the ground (no roots were found), tying them into bundles, and then carefully placing the grass stems on the hut floor, forming an inch-thick cushion.

Ohalo II has the earliest evidence of human bedding yet known, and it illustrates how ancient people constructed space. In the case of Ohalo II, the advantages of the location were obvious: the lake provided fresh water, fish, and waterfowl, wild plants supplied food and building materials, and the shoreline was a nice flat spot for a camp site. But onto that natural landscape, the people of Ohalo II imposed another layer of order: distinguishing areas for cooking and tool making, separating hearth areas and huts, and then taking that extra little step—a soft bed of grass.

Even after 23,000 years, it makes me want to take a nap.

This human propensity towards spatial order is evident in archaeological sites throughout prehistory. Different activities occur in different places. For example, detailed studies of Upper Paleolithic sites in France show how the different stages of butchering reindeer left behind distinctive patterns: the first stages of cutting up the large bloody carcass occurred away from the center of the camp, and leaving behind circular patches empty of bones or artifacts where the carcass had lain, surrounded by bones from less-desirable cuts like vertebrae.13 In contrast, haunches, ribs, and other meaty chunks were carried back to the cooking hearths. At the site of Pincevent it was possible to refit bone fragments from the same reindeer to show how meat was shared among three households.

Another fascinating study of modern hunters and gatherers documented this same human care in making space, even in highly mobile camps only occupied for a few days at a time.

During the 1970s, archaeologist James F. O’Connell spent twenty months studying mobile groups of modern Alyawara, an aboriginal group living in the sand plains and scrub forests of central Australia.14 The Alyawara had been in contact with Anglo-Australians since the late nineteenth century, although sustained contact only occurred after livestock ranches were established in the 1920s. By the time of O’Connell’s study, the Alyawara were tightly tied to Australia’s national economy, working for wages as ranch hands, dependent on government support, and living in large, semipermanent settlements near ranches or on government reserves. Nevert heless, about one-quarter of the Alyawara’s food came from hunting and gathering, and the traces of these activities were evident in their modern, residential sites.

The Alyawara are not fossilized representatives of the Upper Paleolithic, as their camps made obvious. Shelters often consisted of wind-breaks—roofed for shade in the summer or open to capture the warmth of winter sun—built from corrugated sheet metal, brush, and canvas tarpaulins.

As the Alyawara moved through their days, they left behind different clusters of artifacts and domestic debris, concentrations O’Connell referred to as “activity areas.” The larger the household and/or the longer they lived in one place, the larger and more diffuse the activity areas became. With longer occupancies, a distinctive circle of garbage formed around the camp, as the central zone of the camp was swept and trash was redeposited (particularly on the downwind side).

Even when the activities and artifacts were utterly “modern,” their distributions had aspects paralleling ancient hunting and gathering sites. Alyawara men own cars and light trucks, vehicles generally in poor condition and requiring frequent repair. O’Connell mapped activity areas he dubbed “auto repair stations.” These activity areas were adjacent to, but away from, the owner’s household activity area. The auto repair station consisted of an open area 10–20 meters in diameter, surrounded by a dump of parts designed to keep the working area clear of obstacles. Beverage lids and pull tabs clustered under shade trees or sunscreens or in the areas surrounding roasting pits and hearths, while large cans ended up in the peripheral dumps. Households near each other tended to be occupied by closely related women. And, finally, only the very smallest artifacts and debris were found in the places where they were originally used; larger objects were cleaned up and dumped elsewhere in any camp occupied for more than a few days.

But despite other significant differences between the sites, I feel a bemused pleasure in the idea that a group of Alyawara men bent over the chassis of a battered Volvo create an archaeological feature similar to the bloody men butchering reindeer at the Upper Paleolithic site of Pincevent.

. . .

Mobile hunters and gatherers think about landscape in ways that are fundamentally different from those of more sedentary folks, whether fishing or farming communities. The archaeologist Deni Seymour, who has conducted extensive research in the southern American Southwest, highlights the fundamental difference in the way mobile vs. sedentary groups choose places to live. “For mobile groups,” she writes, “the arrival at a residential location involves an appraisal of the character of place…. Whereas sedentary groups establish a place, modify the space, organize within it, structure it, and build it, many mobile groups find an appropriate location and adjust their activities to the circumstance and setting. Thus, it is a ‘selection’ of place rather than a ‘creation’ of place that differentiates mobile groups. This difference is fundamental for understanding the ways mobile groups use space and transform the properties of a place.”15

The ephemeral traces of short-term dwellings are easily overlooked, even in sites that are not particularly old. For example, Seymour has studied the material traces of dwellings at one of the last camps occupied by Geronimo and his band at Cañon de los Embudos, in northern Sonora, Mexico. Harried by the U.S. cavalry and threatened by the Mexican army, Geronimo’s band numbered three dozen men, women, and children. Camped among the rocky ridges, the refugees fashioned circular huts by clearing the stony surface, making a dome of spiny ocotillo stalks—some still rooted and merely bent over and tied—tented with canvas and blankets.

FIGURE 5. Geronimo’s Camp, 1886. Library of Congress.

Obviously, this Apache band was under extraordinary stress, and it would be tempting to see these impermanent huts as the scant shelters of desperate peoples. Yet, as Seymour points out, the archaeological traces of the last camp at Cañon de los Embudos are similar to those found at other Apache sites: circular constructions of fieldstones, “sleeping circles” brushed clear of rocks, and similarly slight modifications of landscape. And while the reason for Geronimo’s mobility (trying to evade impending attack by two different armies) was different, the response was similar to other hunters and gatherers who must frequently move: find a place that meets your needs, use the area, and move on.

Hunters and gatherers approach landscape in varying ways. Food-collecting societies may become more sedentary for different reasons. Some groups are seasonally tethered by the availability of fresh water, plant foods, or other critical resources. Other societies may be constrained by the presence of competing human societies. But one common pattern, as Binford has observed, is that hunters and gatherers tend to become less mobile the further they live from the Equator.

This seems to result from two central facts: 1) there are greater seasonal changes in ambient temperatures the further one moves from the Equator, and 2) the principal advantage of a dwelling is the regulation of heat loss. For example, a detailed analysis of the temperatures created in simple dwellings—replicas of windbreaks, shade structures, and simple huts—found that the real advantages of buildings are marked in colder climates: a domed hut with a warming fire is a better means for controlling temperatures than a sunshade in a hot environment.16 While this seems a fairly obvious conclusion, it suggests that one would expect people to build more substantial dwellings as they moved into more rigorous environments.

That is precisely what occurred in the Upper Paleolithic (at about 45,000 to 13,000 years ago) in Europe during the Last Glacial Maximum. As modern humans migrated from Africa into Eurasia and beyond, they adapted to new and often challenging environments using a variety of technologies—including shelters. Sometime between 37,000 and 34,000 years ago, humans had migrated almost to the Arctic Circle.17 Continental glaciers reached their maximum extents between 33,000 and 26,500 years ago, a period of peak cold.18 As expanding glaciers in western Europe drove people south to the Iberian Peninsula, the vast plains of eastern Europe remained occupied despite its severe climate.19 At this time, temperatures of central and eastern Europe were roughly equivalent to northern and central Siberia today, with cool summers (10°C–11°C/50°F–52°F) and achingly frigid winters (−19°C–−27°C/−2.2°F–−17°F). In eastern Europe a vast expanse of tundra and permafrost steppe fronted the glacial sheet, forming a band of cold grasslands 200–300 kilometers wide. With winter temperatures that plunged below −30°C–−40°C, these periglacial steppes were severe landscapes that nonetheless supported dense herds of mammoths, bison, horses, and reindeer—big game that tempted hunters out onto the icy plains.

To survive in this environment, shelters were as essential as spear-points and flake tools. Huts and tents extended the hunters’ range beyond the limits of rock shelters and caves. As early as 30,000 years ago, structures 5–6 meters in diameter with indoor hearths were erected at sites in western Ukraine and Slovakia. By 25,000 years ago, at the Russian site of Gagarino on the Don River, hunters built circular, semi-subterranean winter homes by excavating shallow house pits 4–6 meters across and raising hide-covered tents. The people of Gagarino warmed themselves by hearths that burned bone on a treeless steppe.20

Bone was used for more than fuel. At a dozen sites in the Dnepr and Desna river basins of Ukraine and Russia, people built their homes from mammoth bones.21

The mammoth-bone huts generally date to 15,000–14,000 years ago, after the Last Glacial Maximum but still sufficiently frigid to create a cold tundra-steppe environment. The sites were located on promontories and terraces, providing a commanding view of the game herds that moved in the river bottoms and ravines.

At Mezhrich (Mejiriche) four mammoth-bone houses were found. The houses are circular or oval, 3–6 meters in diameter, and enclosing a living area of 12–24 square meters. The curving Vs of mammoth mandibles were stacked along the base of the huts’ walls; in one building 95 mammoth mandibles were incorporated into the base of the wall, 40 tusks may have served as roof supports, and a staggering 20,584 kilograms of mammoth bone was used for the dwelling. So much mammoth bone was required, it was necessary to stockpile bone and scavenge natural kill sites. It would have required ten men working four days just to build this house.

Outside, storage pits dug down to the permafrost kept meat cold. Besides mammoth meat, the tundra hunters ate a wide variety of game: ptarmigans and geese, horse, boar, musk ox, and hare. They also hunted for furs, killing ermine, fox, and wolverine.

Deep hearths warmed the inside of the houses and the houses held a wide array of artifacts. Chipped stone blades, scrapers, and burins. Worked bone needles, awls, and shaft straighteners. And there were decorative objects: pieces of amber from sources 100 kilometers away, necklaces and bracelets made from beads of fossilized marine shells from 300 kilometers away.

The massive mammoth-bone houses are amazing dwellings, although not the only places lived in by their occupants. As the archaeologist Olga Soffer points out, the mammoth dwellings represent a single, although essential, element in a larger hunting and gathering strategy. While the mammoth-bone dwelling encampments had evidence for a wide array of activities, other camps reflected a narrower range of pursuits. There were warm-season hunting camps, where dwellings were tents or other lightweight shelters. Sites with storage pits but with no evidence for dwellings were places where game was butchered and cached in the permafrost. Other sites were lithic workshops where stone was quarried and worked, but with little evidence for hunting and no structures. Some of these sites were occupied only once, while the sites with mammoth-bone dwellings were lived in again and again. But all the sites—whether with solid mammoth-bone houses or hide tents—included shelter as the essential tool of the human adaptation.

. . .

The archaeology of ancient hunters and gatherers illuminates the significance of home. The creation of dwellings was a central innovation that allowed humans to occupy the diverse environments of earth, extending humanity’s reach much as the portaledge allows climbers to scale otherwise unattainable peaks. Although our nonhuman primate relatives make nests—and as discussed in chapter 2, chimpanzees actually modify their nests in light of local conditions—only humans create a diverse array of dwellings. Paleolithic dwellings were vital for expansion into higher latitudes, especially during glacial periods. Dwellings allowed humans to range further, exploiting regions and resources inaccessible from rare and stationary rock shelters and caves.

And yet the creation of houses involved more than shelter. Mobile hunters and gatherers used dwellings to map onto landscape, incorporating new regions into the broad spaces that were part of their home ranges. Across that landscape mobile hunters and gatherers made camp. Those encampments varied in duration and placement as people lingered over abundant stocks of food, fled enemies, or buried their dead. For at least 25,000 years, humans have made substantial shelters as elements of a larger cultural strategy. Often, as in the case of Mezhrich, the dwellings became a place of return. When that occurred—and it did so at different places at different times for different reasons—new sets of connections were created between culture and shelter, connections that only intensified and changed as humans became more sedentary.

The archaeology of mobile homes shows how humans organize the spaces where they dwell. Work occurs in certain areas, the dead are buried in others, and—as the excavations at Kebara Cave demonstrate—humans have done this for more than 60,000 years. In open air encampments, people will tend to deal with messy or potentially dangerous tasks on the edge of camp, whether butchering reindeer at Pincevent during the Upper Paleolithic or rebuilding a truck engine in central Australia in the 1970s. This is not, I repeat, because the Alyawara are representatives of the Upper Paleolithic, but because this is what humans do. Whether in a desperate camp in the Sonoran desert or a comfortable encampment on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, we humans order space, we modify our worlds, and in that process we leave archaeological signatures of our passing.