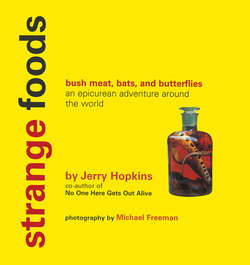

Читать книгу Strange Foods - Jerry Hopkins - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеone man’s meat...another’s poison

About 150 years ago, an eccentric English gentleman named Francis Trevelyan Buckland invited a group of influential Earls and Viscounts and Marquis to dinner and in an attempt to expand their dietary horizons placed the freshly-killed haunch of an African beast on the table at London’s famed Aldersgate Tavern. It was, he said, eland, a large antelope, and he thought they should be imported and bred on the green meadows of Great Britain, to the gustatory delight and nutritional benefit of all its citizens. The crusade that followed the dinner attracted considerable attention in the daily press, but no one seemed much interested in taking it any further, and the eland remained in Africa.

He was a bold man who first swallowed an oyster.

-Jonathan Swift

Buckland was not discouraged. He was raised by eccentric and imaginative parents, and as a child he had eaten dog, crocodile, and garden snails, a habit he kept for life. To a fellow undergraduate at Oxford he confessed that earwigs were “horribly bitter,” although the worst-tasting thing was the mole, until he ate a bluebottle fly. Later, guests at his London home were served panther, elephant trunk soup, and roast giraffe, and it was reliably reported that whenever an animal died at the London Zoo, the curator called the Buckland home.

Buckland pressed on, forming, in 1860, the Acclimatisation Society of the United Kingdom, followed by sister societies in Scotland, the Channel Islands, France, Russia, the United States, the Hawaiian Islands, Australia, and New Zealand. His goal was the same: to introduce new food sources worldwide. In the end, his efforts failed. The world’s dinner table did not welcome Tibetan yak, Eurasian beaver, parrots and parakeets, the Japanese sea slug, steamed kangaroo, seaweed jelly, silkworms, bird’s nest soup, or sinews of the Axis deer, and Buckland died in 1880 in relative obscurity, where he remains today.

Since Buckland’s failed effort, there have been several campaigns, both public and private, underwritten by the United Nations and individual countries as well as by ranchers, academics, and businessmen, to introduce “exotic” foods to the closed diet of what generally is called the “west,” but in fact is epitomized by the gastronomical habits of Europe and North America. (And hereafter will be called Euro-America.) Nearly all have been unsuccessful and many were opposed vehemently.

Then, in 1996, came “mad cow disease,” and when British beef was banned by the European Union, the media published and broadcast stories about ostrich and kangaroo and other beef substitutes. As British Airways added ostrich medallions to its first-class menu and other unusual protein sources appeared in European supermarkets and more wild game became available in North America, a growing number started taking “strange foods” seriously. In Southeast Asia, Australia, and the United States, struggling alligator and crocodile farms found new markets, domestic and foreign. In Singapore, an established investment service began offering ostrich “futures”: invest in a pair of breeders and reap the profits in the sale of their offspring, ranging from twenty to forty a year. From Sydney to Nairobi to Los Angeles, “jungle” restaurants, where game and other exotic dishes were served, became an overpriced trend. At the same time, a few naturalists made an interesting pitch to environmentalists, arguing that the way to save threatened species was to give them commercial value: guarantee their survival by eating them. Once there was a market for these beasts as a food, they suggested, people would start breeding endangered species instead of killing them.

“There are no more than one dozen species of domestic animals which are major food producers around the world,” Russell Kyle argued logically in A Feast in the Wild, a book published in 1987. “If one adds the species with limited, local importance, such as the yak in the Himalayas, or the alpaca in the Andes, there are still fewer than twenty domestic species altogether with a major role as food producers. And yet the world as a whole contains over 200 species of herbivorous animals from the size of a hare upwards. Why have men apparently never considered making more deliberate use of so many wild animals for food production?”

Through history and around the world, what is eaten has varied greatly from time to time and place to place, from one culture to another. Much of the dietary change has resulted from history’s “natural” development—for example, the Portuguese introduced Brazilian chili peppers to Asian cuisine when they started trading there and Marco Polo packed spices and teas back to Europe following his first journeys to China. Similar change continues today as modern travelers return home with a newfound taste for foods experienced abroad, and as more migrants from one part of the world to another take their distinctive cuisines along with them; thus, most if not all Euro-American cities now have sushi bars and Thai restaurants (to name just two examples), unknown only a few years ago. Over the centuries, many other factors have influenced diet, from religious beliefs to hunger to flavor to status to medicinal (and, some insist, aphrodisiacal) properties and more.

What it all comes down to was stated simply and eloquently by M.F.K. Fisher, arguably the best writer about food in the twentieth century, who wrote in a book aptly titled How to Cook a Wolf (1942). “Why,” she asked, “is it worse, in the end, to see an animal’s head cooked and prepared for our pleasure than a thigh or a tail or a rib? If we are going to live on other inhabitants of this world we must not bind ourselves with illogical prejudices, but savor to the fullest the beasts we have killed.

“People who feel that a lamb’s cheek is gross and vulgar when a chop is not are like the medieval philosophers who argued about such hair-splitting problems as how many angels could dance on the head of a pin. If you have these prejudices, ask yourself if they are not built on what you may have been taught when you were young and unthinking, and then if you can, teach yourself to enjoy some of the parts of an animal that are not commonly prepared.”

Calf brains, sheep tongues, chicken feet, pig entrails, fish heads, the list goes on and on. Add “unusual” species such as ants and termites, beetles, bats, water buffalo, algae, cactus, rats and mice, flowers, elephants, whales, grubs, and earthworms, the start of another long list. And, yes, add all those protein sources that so many regard only as pets: cats and dogs, hamsters and gerbils, horses, exotic birds and fish. How many of us would push ourselves away from the table when such dishes were served, as the late Ms. Fisher said, because of what we learned when we were young?

All that said, much regional individuality remains in the world. In Taiwan, serpent blood is a tonic. Many in the southwestern part of the United States swear by rattlesnake steak, just as kangaroo meat is a principal part of the diet for many Australian aborigines and appears on restaurant menus in dozens of Aussie restaurants. A small neighborhood in Hanoi and several in Seoul specialize in dog dishes (not to be confused with dishes from which dogs eat). Bulls’ and sheep’s testicles called Rocky Mountain Oysters are accepted in the American west, while in China, pigs’ ears, fish eyes, and rooster wattle are chopsticked up with gusto. In Southeast Asia, fried locusts are regarded as tasty snacks, just as monkey stew is a staple in parts of Africa and the Amazon, guinea pig is an essential protein source in Peru. Ants and termites are cherished in Africa and South America, yak milk is made into butter in Tibet and then added to tea, and horse-meat has an avid, centuries-old following in France, with another market expanding in Japan. These foods, accepted in one region, are rejected by diners in others. What is considered repulsive to someone in one part of the world, in another part of the world is simply considered lunch.

In the November 22, 1890 issue of the French publication Le Don Quichotte, the French deride acts of cannibalism allegedly taking place in the British colonies of Africa.

I’ve followed Ms. Fisher’s lead and tried to make this book a guide to how the other half dines and why. I’m no Frank Buckland, but over a period of twenty-five years I have rejected my meat-and-potatoes upbringing in the United States frequently to try a wide variety of regional specialties, from steamed water beetles, fried grasshoppers and ants, to sparrow, bison and crocodile, the latter three served en casserole, grilled, and in a curry, respectively. I have eaten deep-fried bull’s testicles in Mexico, live shrimp sushi in Hawaii, mice cooked over an open wood fire in Thailand, pig stomach soup in Singapore, minced water buffalo and yak butter tea in Nepal, stir-fried dog and ”five penis wine” in China, and the boiled blood of a variety of animals in Vietnam. This list, too, goes on, and I share some of these experiences in the chapters following, along with some recipes. After all, no matter what humans eat, by choice or circumstance, the one thing all the dishes have in common is that they must be prepared properly. Of course, there are some people who oppose such exploration. Conservationists are concerned, correctly, about the disappearance of endangered species. Others worry about animal rights, objecting to the manner in which even non-threatened species are penned or caged and slaughtered. A third group-called ”bunny-huggers” in wildlife circles-cries out when people eat animals that they, the protestors, call pets, reminding me of Alice at the banquet in Through the Looking Glass, who turned away the mutton because it was impolite to eat food you’d been introduced to.

The ingredients for a special Balinese version of pepes, a dish cooked in banana leaf packets over an open grill. Garlic, ginger, lime, chillies, fish paste, tamarind paste, monosodium glutamate, coconut paste, and freshly caught dragonflies (less wings).

I will not engage animal rights people in debate. Their point of view is valid and, in fact, carries incalculable weight in a world where resources and environment are being threatened in a manner that is as alarming as it is unrelenting. Many argue that this alone will expand our gastronomical frontiers, whether we like it or not. As Mr. Kyle wrote, cattle are notoriously unkind to the earth and in time there won’t be enough pasture to accommodate the world demand, forcing us to dine on alternate protein sources. The one mentioned most often? Insects.

I don’t insist that you to add ostrich or dog or grasshopper to your menu, although I do suggest that you consider expanding your diet to include something outside the ordinary. However, as a frequent traveler, I do urge anyone who shares my passion for new places and peoples to heed that old but good advice about “when in Rome, do as the Romans do.” Try some of the local food; I believe that it’s a path to understanding the culture better than any other outside learning the language, marrying a native, or converting to the local religion.

Of course, species on the endangered list are not recommended, except under special circumstances. (There are sections on elephants and whales.) There is no need. There are too many other tasty choices.

There also is the matter of curiosity and the pleasant surprise that frequently follows it. “I have always believed, perhaps too optimistically,” Ms. Fisher wrote in a book called An Alphabet for Gourmets (1949), “that I would like to taste everything once, never from such hunger as made friends of mine in France in 1942 eat guinea-pig ragout, but from pure gourmandism.”

Remember the person who first tasted the oyster. It’s not just dinner, it’s an adventure.

The appeal of raw seafood-here abalone, sea squirt and octopus-lies as much in the interesting, often rubbery, textures as in the delicate flavour.

What could be stranger than Space Shuttle food? A dinner of marinated shrimp, noodles, peas, sliced fruit, and candies would make anyone long for comfort food.