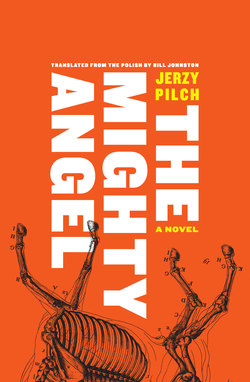

Читать книгу The Mighty Angel - Jerzy Pilch - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 9

ОглавлениеThe Principles of Elusiveness

I was not bothered by Christopher Columbus’s drunken self-deception. One cannot properly drink without self-deception: the lips have to deny the liquor that just passed down the throat. It was surely for the relief of drunkards that the Lord God did not write upon the stone tablets the commandment: thou shalt not lie. The word has to deny the addiction. Among the tribe of alcoholics, lying is a badge of honor—the truth is first an indiscretion, later an affront, and finally a source of despair. If you truly drink, you have to announce to all and sundry that you do not drink; if you admit you drink, that means you do not truly drink. True all-out drinking has to be concealed; anyone who reveals it is giving in, confessing to helplessness, and all that remains for him is weeping, the gnashing of teeth, and the twelve-step program.

Whenever I tell you that I’ve stopped drinking, that I don’t drink, that after all these decades I’ve sobered up for good, that I’ve regained my sense of time, that I spent weeks recovering in an ice-cold house in the mountains—you can always calmly disbelieve me. Truly, you shouldn’t believe a single word I say. The word is my stimulant, my narcotic, and I’ve acquired a taste for overdosing. Language is my second—what am I saying, second—language is my first addiction.

Regardless of whether I’m talking sober or talking drunk, whether I say that from morning to night I’ve been drinking peach vodka, or that for a hundred and sixteen days not a single drop has passed my lips—regardless of what I say, in my talking I am elusive even to myself. Just as in my drinking I am elusive to myself and to the entire world.

How often is it, for example, that I’ve been striding down Szewska Street in Kraków sober as an angel, and I’ve not gone twenty yards, not twenty seconds have gone by, I’ve only gone sixteen yards and only sixteen seconds have passed, I enter the Market Square and in the blink of an eye, entering the Market Square, first of all, I myself render my angelhood human, then subsequently my humanity undergoes a rapid bestialization of its own accord, and in the blink of an eye, entering the Market Square, I’m as drunk as a beast. What has happened? Has the silver turret of my soul disintegrated into rubble? Has a black wind appeared to hurl me into the abyss and sit me on a high stool? What has happened? I don’t know. My not drinking on Szewska eludes me, and my drinking on the Market Square eludes me too.

I am the prince of elusiveness. When I say I do not drink, it is certainly the case that this is not true, but when I say I drink, I could equally be lying through my teeth. Don’t believe me, don’t believe me. A drunkard is ashamed to drink, but a drunkard has an even greater source of shame—he’s ashamed not to drink. What kind of drunkard doesn’t drink? The lousy kind. And what’s better: lousy or not lousy? What is superior: lousiness or not-lousiness? And besides—when one’s drunken destiny is about to be fulfilled, it’s not only futile but also indelicate, and even dishonorable, to try and get the better of that destiny.

When the Hero of Socialist Labor, a venerable foundry worker from the Sendzimir (formerly Lenin) Steel Mill, finally understood his own helplessness during one of his stays on the alco ward—when he understood that his drunken destiny had been fulfilled and had closed over him like a mound of earth over a mass grave—he was stupefied, and spent days on end standing outside the men’s bathroom, tears perpetually flowing down the gray stubble that covered his cheeks. He stood there outside the can like a monument to stupefaction and kept repeating:

“How can you not drink when everyone drinks? How can you not drink when everyone drinks? How can you not drink when everyone drinks? How can you not drink?”

And the poor fellow would have stood there till the Day of Judgment, he would have stood there till the day he was discharged from the alco ward, he would have stood there and wept, had Dr. Granada not called him into his office at a certain particularly desperate moment, sat him down in an armchair, and addressed him in more or less the following words:

“Soon you’ll be leaving here, Mr. Hero, and after you leave, if you manage not to drink, then don’t drink, with all your strength don’t drink, but announce to all and sundry that you’re drinking. That way you’ll avoid a great deal of stress that will push you to drink, you’ll avoid a great deal of pain, unpleasantness, indignation even. You’ll avoid glances filled with disappointment and expectations of the worst. You worked hard to earn your drunkard’s role, Mr. Hero, and right now it’ll be better both for you and your weakened health if you don’t unnecessarily complicate your own image. You entered our doors as a drunkard and for your own psychological well-being and the peace of mind of your closest friends you’ll leave here as the same drunkard, yet in reality you’ll merely be wearing the costume of a drunkard. You should not drink and you should assert openly, or give others to understand with plain hints, that you drink. Lie as long and as persistently as you’re able about drinking, especially since sooner or later you’ll start anyway.”

And the tears instantly dried on the gray stubble that covered the cheeks of the Hero of Socialist Labor, and a great weight was lifted from his heart, and he left Dr. Granada’s office with brightened visage, and after he left the office his visage shone more brightly still upon the rest of us.