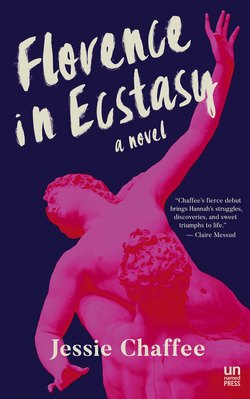

Читать книгу Florence in Ecstasy - Jessie Chaffee - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One

“Signorina.”

Signora Rosa. Such a delicate name. She must be someone’s grandmother, stout and soft with a halo of white hair; this had tricked me into thinking that she would be soft with me. But she is all hard edges. No sooner have I closed the door than she is there on the stairs with that same side-eyed look. Why? It is almost September. Almost a new month. Only cash, she’d said when she agreed to rent me this bright apartment, even though it was caro, caro, caro. Only cash. Up front.

“Signorina,” she rasps. A term meant for someone much younger than me, a little girl, and I’d like to upend her assumptions, tell her I had every intention of paying her, but I can’t form the words. Instead I mumble, “Sì, sì, mi scusi, momento,” and scurry around the corner to the bank to face my dwindling funds. I have enough to get through September, and that will be it. Every last cent. But as soon as I hand her the bills in that old stone lobby, I feel free.

And then I walk. Every morning I walk, circling the bones of Florence, treading a well-worn path through the bodies of transients to whom I am invisible. Today I walk until my skin is on fire and my legs are slick and shaking. Until I’m ill with the smell of sewage that the heat pulls from every crevice. Until I grow dizzy and my mind grows numb and I arrive at the place where I always end these walks: by the wall of the Arno River at the city’s center. I lean into it, feel the heat coming off the stone, feel the bodies pressing against me, tourists burrowing in to snap photos of the Ponte Vecchio, their cameras storing the same image again and again.

The rowing club sits below on a narrow embankment in the bridge’s shadow. It is a launching point for the boats that, even in this heat, cut lines up and down the lazy Arno. For days I’ve watched from this perch the young Italian men carrying sculls down to the river. There is something calming in their movements, in the quiet way that they shoulder those boats, like pallbearers, and lay them down on the water’s surface.

But today is different. Because for the first time, a woman emerges on the embankment, a boat balanced on her shoulder, oars balanced on her hip. She is alone. She is at ease. I watch as she lowers the body into the water, slides one oar into the metal U-ring, then the other. She pauses, glancing up and down the Arno—there is no one else out yet, it is hers alone—then steps carefully into the shell. She nudges the dock with one hand, and the river offers no resistance as she pushes off gracefully, adjusts the oars, and begins her course, making her way toward the next bridge with purposeful movements. It is a separate existence, one far from this city with its crush of bodies and sounds and smells. I watch until she disappears from sight, a single body at peace.

Tucked into the busy street behind me is a green door that I have also watched on these mornings and, beside it, a small plaque—SOCIETÀ CANOTTIERI FIRENZE, it reads, “Florence Rowing Club”—half hidden by a vendor’s cart heavy with belts hanging thick and dark like vines. To the right is the long courtyard framed by the arms of the Uffizi Gallery; to the left is this green door.

Today will be different. I inhale sharply and push against bodies, launching myself across the street. But before I reach it, the door swings open with a rush of cool air, and a group of teenagers clambers out, jostling by me with a chorus of permesso, scusi, permesso. Another figure is behind them. A man, tall, with dark hair brushed back.

“Attenzione, ragazzi,” he calls as they disappear down the street in an explosion of sound. “Scusi, eh?” he says to me, his hand propping the door. The skin gathers around his eyes in bursts as his cheekbones stretch to accommodate an expansive smile. I feel surrounded by it.

“Dove va?” Where are you going?

I look past him into the darkness, my face still hot from my walk, my dress sticking.

“Mi dica,” he says then.

Tell him what? “Questa è la Canottieri Firenze?” The words catch strange in my mouth, half swallowed.

“Sì, sì.” He gestures for me to enter. “Che cosa vuole, signora?”

“Vorrei…” I put my arms out to the surroundings, foolish, and I can smell my sweat now. It smells sour to me, acrid, like an infection—it has for months, and I don’t know if it is my sense or the odor that has changed. “To join,” I say finally, hugging my arms back to my sides.

“Va bene,” the man says, and chuckles. He pushes the door open wider. “Allora, you must speak with Stefano.”

“Grazie,” I mumble, scooting past him into the dark foyer.

“Certo. Arrivaderla, signora, arrivaderla.” I hear him still laughing until the door abruptly shuts, taking with it the heat, the light, and this laughing man.

I walk down a flight of steps, blind until my eyes adjust—an office glowing fluorescent, another door. There is no one here. I should leave. But I think about the woman on the water, and then I hear distant punctuations of sound that must be human. Stefano. I cling to the name and keep going, through the door and down more stairs. I am tunneling into a cave, a warren, down and down until I reach a low stone doorway I have to bend under to clear, and when I do, I’m accosted by the smell of coffee and sweat. A little bar filled with tables, and daylight beyond. An old man in a unisuit looks up from his paper, squinting like an angry gnome. I wait for him to ask me a riddle, but he shakes the paper and lowers his eyes.

Behind the counter a man with a white mustache fills a glass with bright pink juice. He’s watching me. “Buongiorno,” he says. “Americana?” He places a spoon in the glass, then points to himself. “Manuele.”

“Hannah.” I relax. No riddles, no tricks. “Is Stefano here?”

“Anna,” he says, losing the h. “Anna di…” He raises his eyebrows.

“Di Boston.”

“Anna di Boston—ecco Nico.” He nods at the old man, who sighs and shuffles to the counter.

“’Sera,” he mumbles, before taking a sip of his juice.

Manuele winks, then calls, “Stefano!” and a third man appears in the sunlit doorway. He’s tall and deeply tanned, his mouth a sharp line. Manuele speaks to him too quickly for me to follow until I hear “Anna di Boston.”

“Hannah,” I say. “I’d like to join. The man upstairs told me—”

“Sì, certo.” Stefano’s smile is still tight, his brow now furrowed. “You row?”

“No.”

“Never?”

I hesitate. I know how I must look to him—it is written across me in spaces and hollows. But I’ve come this far, and so I continue. “No. I’d like to learn, though.”

Stefano says nothing, then, “Va bene. You’ll learn. Andiamo,” and gestures for me to follow him out into the sunlight. Above us, the Ponte Vecchio sprawls, a triple-bellied beast, reflections catching in its arches and water pouring between its supports like a churning shadow. Tourists lean over the river’s wall where I stood moments before, but that world is distant now. It feels like the city itself has opened up, as though I’m peering out at it from the inside.

“Oh,” I exhale softly.

“Bello, no?”

I look around for the woman I’d seen, but the river is empty, and there is no one on the stretch of grass or the long brick steps that lead to the Arno’s edge.

“Today it is quiet,” Stefano says, “because of vacation. But tomorrow people will return.” Then, in a mixture of English and Italian, he explains that this was originally a stable for the Medici horses. As he speaks, his smile loses its tension. He is the club’s manager and his father was before him.

“Hey, Stefano,” a young man says brightly as he passes us on his way down to the dock.

“He’s American, too,” Stefano explains. “A student.” He leads me back inside and shows me the locker rooms, the weight rooms, then walks me down a dark, boat-lined corridor—at the end, an old man is tending to one of the sculls, laid out like a body before him. He gently polishes its bowed wooden sides.

“Ciao, Correggio,” Stefano calls, before leading me into a room crowded with rowing machines. Against one wall is a raised pool of water, four sliding seats balanced along its lip. “For practice in the bad weather,” he says. “This is a special room. You know why?” I look at the quiet ergometers, the placid water, our reflections in the mirrored wall, until Stefano points to the ceiling, smiling wryly: “Uffizi,” he says, letting me in on the secret. “C’è state?”

“Of course.” I smile, really smile, for the first time in days, maybe weeks. We’re right below the museum. I imagine the crowds wandering the galleries above, and that could be me, had been me, and yet in a month, a day, a single afternoon, you can become something new, can become undone but also transformed.

And so when Stefano tells me the cost of membership and says, “It’s okay?” I nod, though I barely have enough to get through the month, but still I nod.

“It’s perfect,” I say.

“Okay. Tomorrow my assistant is back—you register with her. Then you begin here, in this room—to practice, to learn, okay? One week, two weeks. And then the river!”

“So quickly?”

“Sì. Certo. And why not?”

“And why not,” I echo, taking the warm hand he offers me.

Before I leave, I walk up and down the hallway lined with wooden boats. They are overturned on shelves, spines raised, bodies stretched, stacked floor to ceiling in rows running from the largest eight-man boats to the small one-man sculls at the far end. I have the sensation of the past hovering just below the present, as I so often do here, my own past leaping out, fast and fierce, and suddenly I remember. I walk slowly, examining the names stenciled in white block letters along their sides—FORTUNATO, BOREA, PERSEFONE. I search for inconsistencies in the repeated symbol of the red-and-white rowing flag that ripples across each boat, trying to find a place where the human hand had wavered.

Boston. The museum was dark. It was a Monday in July and after hours—it had been planned this way, so that I could come and go barely seen, and now I was going, or was supposed to be. I ducked into the bathroom, eyed my face in the mirror, hollowed. I threw up.

Then I walked through the vacant galleries, clutching the envelope—a severance, handed to me with lowered eyes because I had brought myself to this place, to the bottom—until I reached the painting. A sea-filled nocturne. Blue and silver, but up close, mostly gray, a fog heavy with shadows, the only break in the haze a few orange gestures, the brightest near the center—a fire on a distant shore?—but so faint and far off you knew you’d never reach it. That was how I had felt. For years, maybe. As though everyone around me had figured something out that I couldn’t quite grasp. And so I remained in this fog.

I was exhausted, in fact I could barely stand, but still I stopped in front of this painting to stare at that bit of orange near the center, that place beyond this place where I found myself, inexplicably. I put my hand out to touch it—and why not? what could they do to me now?—to touch, only lightly, that vanishing point where everything disappeared and came together. It was a shallow valley, rough under my finger. I felt the events of the previous months slipping away. I felt a door opening, the crack widening into something I could slip through.

“Hannah?” A voice came from the end of the corridor and I hurried out into the gray summer evening without looking back.

I choose my evening meals in Florence carefully. Early on I made the mistake of going to a traditional spot, candlelit, with couples who eyed me suspiciously. I had not anticipated such stares. Disapproving and reproachful, they presented a uniform front, said, This place is ours, as I took too long reading the menu, inevitably falling on the contorni—the side dishes—and then ordered quickly, avoiding the waiter’s skeptical gaze: È tutto? Yes, that’s all. When my small plates arrived, the stares returned, the pairs glancing up from their own dishes piled high with meat or pasta—glistening, those items stared at me, too. I took in their stares and ate quickly.

So I choose carefully. There is Fuori Porta, or “Outside the Gate,” a wine bar just beyond one of the city’s large doors, the last lit building in a trendy quarter before the road winds up into the dark hills. Between six and nine each night, appetizers line the counter. I dine on pickles and carrots. I drink three glasses of wine. I listen to the hum. When the young bartender asks if I would like a fourth glass, I smile and say no. I’m meeting a friend for dinner, I think, for all he knows. I always leave Fuori Porta feeling better. Something in the walk home through the silent streets, past the dusty buildings, and across the Ponte alle Grazie—bridge of thanks—leaves me lighter.

And then there is Shiso, a sushi place where I go when I feel alert enough to face conversation with the owner, Dario. Tonight I turn the corner to find him arguing with one of the drunkards who fill the square outside—their hair is stringy with grease, their eyes drained of color. Sometimes I feel their hot breath as I pass and a phrase is thrown my way, but they go no further. I am no threat to them. And there is something of them in me, too.

“Dai! Dai!” Dario shouts at one of these shades, a cigarette hanging from his hand. When he catches sight of me, he drops his voice low and presses something into the man’s palm. Then he throws his shoulders back and inhales deeply, looking off into the distance as the man disappears down the alley. He’s pretending he hasn’t seen me.

“Ciao,” he says, overly familiar once I’m upon him. “Come stai?”

“Bene. How are you?”

“Busy, always busy,” he says with a sigh. This is his mantra, though there are never more than a handful of people in the restaurant. I am, I believe, his only repeat customer.

He puts out his cigarette and opens the door, placing a hand on my elbow to guide me in. The interior is steel and red, about a decade too late to be modern. This place is his passion, opened after his travels in Japan. He explained it all to me one evening. Very good, I lied, picking at the small strips of overpriced fish. Because it’s good, sometimes, to be known. I let him walk me home one night, let him kiss me outside my door. But not tonight. Tonight will be different.

There is only one table occupied—a young American couple—and the waitress, unsmiling, doesn’t move from her post by the kitchen. Dario wipes down the counter and pours me a generous glass of wine.

“A good day?” he asks.

“Very good,” I say, meaning it for the first time.

“You are lucky to be on such a vacation. For me it is always work, always busy. What is your work—in Boston?”

It catches me off guard. “I do fund-raising,” I say, as though it were still true. “For a museum.”

“Cosa?”

“I work with art.”

“Ah. An artist.”

I don’t correct him. What would be the point of explaining that my job had nothing to do with art—though that was why I’d taken it—and everything to do with money. I was good at it at first. Pretending that I gave a shit, I mean. Pretending that it mattered.

“Then you understand what it is,” he continues, “to be always busy.”

I nod. His confidence is aggressive and catching, and I, too, act as though I don’t see the empty tables, the waitress’s frown as she takes my order, the sweat that beads on Dario’s forehead and scalp where his hair is thinning. I accept a second glass of wine and eat slowly once my food arrives, thinking back on the day. Dario crosses his thick arms and commences a fresh monologue.

“I have this place for three years, you know. Tre anni, almost.”

As he speaks, I begin my necessary ritual—the list. I construct it carefully in my mind.

“I think, sometimes…”

The coffee this morning—no milk, no sugar.

“…è brutto, Hannah. Davvero.”

On top of it I place the toast—two slices, choked down.

“Sicilia. Penso di…”

The salad, after my walk, is more challenging.

“…è sempre la stessa cosa.”

I nod. Dario pauses, refills my glass.

“Allora I go on vacation…”

I start over: break the list up into compartments, slide the toast to one side, put the wine in its own square—a larger square, it’s true. Alcohol counts, isn’t air, I know this. But it gets me through, so I account for it. Leave room.

“…è diverso…”

I return to the salad. Take it apart. Compress the pieces.

“…che cazzo…”

A roll of green. Slivered tomatoes. A sheet of cheese, almost translucent.

“…non voglio ma…”

There is no place for the almonds, a handful this evening before going out.

“…è un casino.”

Finally the salmon. Five pieces. Slimy. I feel them already swimming in my stomach.

“She says to me, ‘Dario…’”

Then I stack the items, one on top of the next. They become a tower, tall and spindly.

“Che posso fare?”

But it does not feel spindly, this tower. I feel the weight of it.

“Così è la vita…”

The almonds sit to the side, disturbing. I cannot place them on top.

“…però in futuro…”

I dare not.

“…credere—” Dario’s phone rings. “Cazzo,” he bellows, picking it up and walking quickly to the corner of the bar.

I look again at the tower. Close my eyes. Try to figure it out. Start over.

Giggling behind me. I open my eyes. In the mirror I can see the American couple—they are looking this way, the woman with her hand over her mouth. Why? I look at my reflection. What does she see? A woman, almost thirty, older than her, I must be older than her, my face drawn and serious. My hair is limp. I blew it dry before going out, in spite of the heat, and it should frame my features, dark. But it didn’t work and it’s gone limp, sits flat, hangs to my shoulders in strings. Like the men outside. Like dribble. Strings of dribble.

There is something I’ve forgotten to do. Somehow during the day, over the course of this evening, I lost it. I try to focus, to grasp it, but it’s gone, out of reach, disappeared. Why can’t I hold on to anything? Always it slips and slips and slips.

A voice shouting. Is it mine? No. Outside. A man is shouting at someone or something in the street.

“Magari.” Dario sighs loudly. “Hai visto? What I have to do. Always busy.” He disappears outside, and I open my purse and leave money on the counter. Too much I think, but I’ll go. Before Dario comes back and I let him walk me out, I’ll go. I glance quickly for the waitress, but she’s disappeared as well. There’s only the smug couple now.

Outside it is dark, but still the air sticks. I hear raised voices behind me and they chase me on. The stones catch my heels, echoing loud each time. There is something I’ve forgotten to do. My street is empty and the music from the club beats loud. The door of the building feels heavy, the air in the lobby is heavy, too. I hit the switch of the timed light and, with a click, the stairwell illuminates but goes dark by the time I reach the third floor. I put my hand on the wall and find my way up, my steps loud and clumsy, and somewhere below a door opens.

“Signorina?” The landlady—what else does she want from me?—and I speed up, catch my thigh on the edge of the banister rounding the corner. It feels hot, spreads, will bruise. I hear the phone ringing, shrill, as I get to my landing.

Yes, that’s it. I’ve forgotten again. Four, five, six rings. I find my door, put the key in the lock. Turn one, two, three times. The ringing continues. Seven, eight, nine. The door swings in and the sound pierces. Ten, eleven, twelve.

“Hannah?” My sister’s voice hits like cold water, pulls me in. Even this far away, I feel pulled. Weighted. I breathe in, breathe out.

“Honey, are you okay?”

I nod. I will not cry.

“Hannah?”

“I’m fine. I just hurt my leg.”

“What? What do you mean?” Kate is suspicious. She is always suspicious.

“Nothing. I don’t know. I just got home.”

“The list, Hannah. It’s been five days. You didn’t—”

The list. My inventory. The tower swims in front of me now in the dark. Laughter bubbles up from downstairs. “Bastardo!” a man shouts. More laughter.

“You can’t do this, Hannah.” I see her seated on a stool by her counter, dialing and redialing, intent on mending. She is a mender.

“I’m fine.” I see the words and then say them. “I’ve just been busy.”

“With what? What do you do all day?” She stops. “I’m sorry. How are things?”

“I went out to dinner,” I say. “And I was going to write you, but I forgot.”

“Hannah, you can’t forget. That’s the deal.”

That is our agreement. Every three days: the list. That and no scales—but Kate doesn’t know about the orange scale, purchased on my first day here. And I do send the list. Today was different, though, and my words begin tumbling now, spilling out of me as I explain—the meal, the wine, the men, the shouting, the wad of money left on the bar. “Too much, but I needed to leave before Dario came back. And then I forgot to write you. Because of everything that was happening.”

I’ve fucked it up. I know it before she speaks.

“What are you talking about? Who’s Dario?”

I think through it. The mirror, the almonds, the shouting. There’s an answer in it I can’t find. It slips and slips and slips. I give up—it won’t make sense to her. Kate breathes in sharply, and I can see her looking out her window as though she can see me all these miles away.

“We’ll talk about it next week,” she says. “When you’re back.”

And now I’ll have to tell her. “I’m not leaving.”

“What? Are you—”

“I’m staying. A little while longer. I already changed it—my ticket. It’s done.”

“Are you sure? Don’t you think it’s time to come home? To start looking for work? Have you started looking? Or don’t worry about that. You can stay with us.”

“No,” I say quietly.

“Hannah—” Her voice catches. “You can’t just disappear.”

That’s what she’s afraid of, my total erasure. I am disappearing. But not anymore. Not anymore.

“This was supposed to be a break,” she pleads. “A break. That’s what you said. But it’s been a month. What are you going to do for money? How are you going to live?”

“I’m fine,” I say, focusing on the words.

“I don’t understand this. I don’t know what to do.”

It is the same voice I heard months ago, when I had gone as deep and as low as I would go. The voice that reflected back to me the rock bottomness of my existence.

“Won’t you come home?”

My anger surges up, cuts through the fog, and I’m surprised at the growl in my voice when I say, again, “No.” It doesn’t sound anything like me. It’s mine, I want to say. I don’t know what it is, but it’s mine.

Kate is crying now. I need something—something to convince her. And then an image emerges from the fog of the day. The woman on the water, her body at peace.

“I’ve been rowing,” I say. “I joined a rowing club. It’s helping. It’s beautiful on the river. Quiet.” And it’s not really a lie—not if I make it true, which I will. If I can just get past this call, get to sleep, get to the next morning with its clean slate.

“That sounds nice,” Kate says softly. Then, “Call tomorrow. Call tomorrow when you’re feeling better.”

I hang up the phone and take off my skirt, my body racing. I lie down on my bed. Dinner seems far away now. The club seems far away. Home, farther still. I am propped up here without a backdrop. I am stiff, straight. Not soft like my sister, as I should be. She is a question mark, I think, before I fall asleep. Miles away, curled in the dark, she is a question mark and I am an exclamation point. And it seems to make everything come clear that all I need is to become a question mark again.

Tomorrow, I will begin to bend. I will begin tomorrow.