Читать книгу Marilyn and Me - Ji-min Lee - Страница 6

A Day in the Life of Miss Alice of Seoul

ОглавлениеFebruary 12, 1954

I go to work thinking of death.

Hardly anyone in Seoul is happy during the morning commute, but I’m certain I’m one of the most miserable. Once again, I spent all last night grappling with horrible memories—memories of death. I fought them like a girl safeguarding her purity, but it was no use. I knew I was under an old cotton blanket but I tussled with it as if it were a man or a coffin lid or heavy mounds of dirt, trusting that night would eventually end and death couldn’t be this awful. Finally, morning dawned. I looked worn out but tenacious, like a stocking hanging from my vanity. I used a liberal amount of Coty powder on my face to scare the darkness away. I put on my stockings, my dress, and my black, fingerless lace gloves. I walk down the early morning streets as the vicious February wind whips my calves. I can’t possibly look pretty, caked as I am in makeup and shivering in the cold. Enduring would be a more apt description. Those who endure have a chance at beauty. I read that sentence once in some book. I’ve been testing that theory for the last few years, although my doubts are mounting.

As always, the passengers in the streetcar glance at me, unsettled. I am Alice J. Kim—my prematurely gray hair is dyed with beer and under a purple dotted scarf, I’m wearing a black wool coat and scuffed dark blue velvet shoes, and my lace gloves are as unapproachable as a widow’s black veil at a funeral. I look like a doll discarded by a bored foreign girl. I don’t belong in this city, where the ceasefire was declared not so long ago, but at the same time I might be the most appropriate person for this place.

I get off the streetcar and walk briskly. The road to the US military base isn’t one for a peaceful, leisurely stroll. White steam plumes up beyond the squelching muddy road. Women are doing laundry for the base in oil drums cut in half, swallowing hot steam as though they are working in hell. I avoid the eyes of the begging orphans wearing discarded military uniforms they’ve shortened themselves. The abject hunger in their bright eyes makes my gut clench. I shove past the shoeshine boys who tease me, thinking I’m a working girl who services foreigners, and hurry into the base. Snow remaining on the rounded tin roof sparkles white under the clear morning sun. Warmth rolls over me as soon as I open the office door. This place is unimaginably peaceful, so different from the outside world. My black Underwood typewriter waits primly on my desk. I first put water in the coffee pot—the cup of coffee I have first thing when I get in is my breakfast. I can’t discount the possibility that I work at the military base solely for the free coffee. I see new documents I’ll have to translate into English and into Korean. These are simple, not very important matters that can be handled by my English skills. First, I have to notify the Korean public security bureau that the US military will be participating in the Arbor Day events. Then I have to compose in English the plans for the baseball game between the two countries to celebrate the American Independence Day. My work basically consists of compiling useless information for the sake of binational amity.

“It’s freezing today, Alice,” Hammett says as he walks into the office, smiling his customary bright smile. “Seoul is as cold as Alaska.”

“Alaska? Have you been?” I respond, not looking up from the typewriter.

“Haven’t I told you? Before heading to Camp Drake in Tokyo, I spent some time at a small outpost in Alaska called Cold Bay. It’s frigid and barren. Just like Seoul.”

“I’d like to visit sometime.” I try to imagine a part of the world that is as discarded and ignored as Seoul, but I can’t.

“I have big news!” Hammett changes the subject, slamming his hand on my desk excitedly.

I’ve never seen him like this. Startled, my finger presses down on the Y key, making a small bird footprint on the paper.

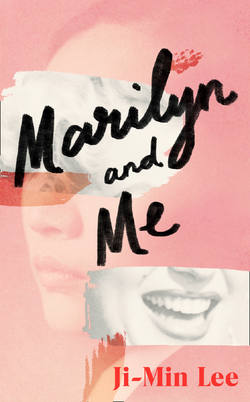

“You heard Marilyn Monroe married Joe DiMaggio, right? They’re on their honeymoon in Japan. Guess what—they’re coming here! It’s nearly finalized. General Christenberry asked her to perform for the troops and she immediately said yes. Can you believe it?”

Marilyn Monroe. She moves like a mermaid taking her precarious first steps, smiling stupidly, across the big screen rippling with light.

Hammett seems disappointed at my tepid response to this thrilling news. To him, it might be more exciting than the end of the Second World War.

“She’s married?” I say.

“Yes, to Joe DiMaggio. Two American icons in the same household! This is a big deal, Alice!”

I vaguely recall reading about Joe DiMaggio in a magazine. A famous baseball player. To me, Marilyn Monroe seems at odds with the institution of marriage.

“Even better,” Hammett continues, “they are looking for a female soldier to accompany her as her interpreter. I recommended you! You’re not a soldier, of course, but you have experience. You’ll spend four days with her as the Information Service representative. Isn’t that exciting? Maybe I should follow her around. Like Elliott Reid in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.”

Why is she coming to this godforsaken land? After all, American soldiers thank their lucky stars that they weren’t born Korean.

“We have a lot to do—we have to talk to the band, prepare a bouquet, and get her a few presents. What do you think we should give her? Folk crafts aren’t that special. Oh, what if you draw a portrait of her? Stars like that sort of thing.”

“A portrait?” I stammer, flushing all the way down my neck. “You can ask the PX portrait department—”

Hammett grins mischievously. “You’re the best artist I know.”

My mouth is dry. “I—I haven’t drawn anything in a long time.” I am as ashamed as an unmarried girl confessing she is pregnant. “And—and—I don’t know very much about her.”

“There’s nothing easier! People with faces that are easy to draw are the ones who become stars anyway. You don’t have to know anything about her. She is what you see.” He’s having a ball but then sobers when he catches my eye. That sharp gaze behind his good-natured laughter confirms the open secret that he probably is an intelligence officer. “Why don’t you draw anymore, anyway? You were a serious artist.”

I’m flustered and trapped, and my fingers slip. Letters scatter across the white paper like broken branches. He might be the only one who remembers the person I was during more illustrious times. Among the living, that is. “No, no. If I were a true artist I would have died in the war,” I murmur, and pretend to take a sip of coffee. My words leap into my coffee like a girl committing suicide. The resulting black ripples reverberate deep into my heart.

I leave work earlier than usual and take the streetcar to Namdaemun Gate.

A few months before the war broke out, a thoughtful someone had hung a Korean flag, an American flag, and a sign that exclaimed, “WELCOME US NAVY!” from the top of the centuries-old fortress gate. Perhaps thanks to its unceasing support of the US military, Namdaemun survived, though it suffered grievous wounds. I look at the landmark, the nation’s most famous disabled veteran, unable to offer any reassuring words. As if confused about how it survived, Namdaemun sits abjectly and seems to convey it would rather part ways with Seoul. I express my keen agreement as I pass it by.

The entrance to Chayu Market near Namdaemun teems with pedestrians, merchants, and American soldiers. All manner of dialects mingle with the pleasant Seoul accent and American slang. I fold my shoulders inward and try not to bump into anyone. The vitality and noise pumping out of the market are as intense and frightening as those on a battlefield. I am unable to keep up with the hunger for survival the people around me exude, so I make sure to stay out of their way. I duck around a fedora-wearing gentleman holding documents under his arm, a woman with a child on her back with an even larger bundle balanced on her head, and a man performing the acrobatic trick of napping on his feet, leaning against his A-frame. I head further into the market.

At Mode Western Boutique, I find a group of women from the market who are part of an informal credit association. Mrs. Chang, who owns the boarding house I live in, also owns the boutique and oversees the group. The women are trading gossip over bolts of shiny Chinese silk and velour, but when I walk in they poke at each other, clamming up instantly. I’m used to their curious but scornful glances. I pretend not to notice and shoot Mrs. Chang a look in lieu of a greeting. Mrs. Chang swiftly collects the bills spread out on her purple brocade skirt and stands up.

“Ladies, you know Miss Kim, one of my boarders? She’s a typist at the base. Don’t you embarrass yourselves by saying anything in English.”

The women begin exchanging smutty jokes and laughing. With the women otherwise occupied, Mrs. Chang ushers me into the small room at the back of the shop. She turns on the light, revealing the English labels on dizzying stacks of cans, cigarettes, and makeup smuggled out of the base.

“Here you go.” I take out the dirty magazine I wrapped in pages torn out of a calendar. I asked an accommodating houseboy to get me a copy.

Mrs. Chang glances outside and gestures at me to lower my voice. She flips through the magazine rapidly and frowns upon seeing a white girl’s breasts, as large as big bowls. “Even these rags are better when they’re American-made,” she says, smiling awkwardly. “A good customer has been looking for this. I’ve been searching and searching, but the ones I come across are already fairly used, you know?”

I turn away from Mrs. Chang’s feeble excuse.

Mrs. Chang shows these magazines to her impotent husband. She lost all three of her children during the war. That is sad enough, but it’s unbearable that she’s trying for another child with her husband, who stinks of the herbal medicine he takes for his ailments. It’s obscene to picture this middle-aged woman, whose lower belly is now shrunken, opening Playboy for her husband who can barely sit up as she pines for her dead children. It’s too much to handle for even me.

“I’m sorry I had to ask an innocent girl like you to do an errand like this for me,” she says.

“That’s all right. Who says I’m innocent?”

Mrs. Chang studies me disapprovingly. “Don’t stay out too late. I’ll leave your dinner by your door.” Although her words are brusque, Mrs. Chang is the one person who worries about whether I’m eating enough.

Having fled the North during the war, Mrs. Chang is famously determined, as is evident in her success. She is known throughout the market for her miserly cold-heartedness. That’s how pathetic I am—even someone like her is worried about me.

We met at the Koje Island refugee camp. In her eyes, I’m still hungry and traumatized. I was untrustworthy and strange back then, shunned even by the refugees. I babbled incoherently, in clear, sophisticated Seoul diction, sometimes even using English. I fainted any time I had to stand in line and shredded my blanket as I wept in the middle of the night. I was known as the crazy rich girl who had studied abroad. I cemented my reputation with a shocking incident and after that Mrs. Chang took it upon herself to monitor me. When she looks at me I feel the urge to show her what people expect from me, though I doubt she wants me to. People seem to think I have lost my will to stand on my own two feet and that I will fall apart dramatically. I’m not being paranoid. I haven’t even exited the boutique and the women are already sizing up my bony rump and unleashing negative observations about how hard it would be for me to bear a child. They wouldn’t believe it even if I were to lie down in front of them right now and give birth. Somehow I have become a punchline.

Alice J. Kim. People do not like her.

Women approach me with suspicion and men walk away, having misunderstood me. Occasionally someone is intrigued, but they are a precious few; foreigners or those whose kindness is detrimental to their own well-being. People don’t approve of me, beginning with my name. “Alice? Are you being snooty because you happen to know a little English?”

Very few know my real name, or why I discarded Kim Ae-sun to become Alice. I’m the one person in the world who knows what my middle initial stands for. Only whores or spies take on an easy-to-pronounce foreign name—I am either disappointing my parents or betraying my country. People think I am a prostitute who services high-level American military officers; at one point I was known as the UN whore, which is certainly more explicit than UN madam. But I was just grateful to be linked to an entity that is working for world peace. Or else they say I’m insane. Now, to be a whore and insane at the same time—if I were a natural phenomenon, I would be that rare unlucky day that brings both lightning and hail. People will occasionally summon their courage to ask me point-blank. Once, an American officer took out his wallet, saying, “I’d like to see for myself. Do an Oriental girl’s privates go horizontal or vertical?” I told him, “Every woman’s privates look the same as your mother’s.” The officer cleared his throat in embarrassment before fleeing. Anyway, in my experience, a life shrouded in suspicion isn’t always bad. No matter how awful, keeping secrets is more protective than revealing the truth. Secrets tend to draw out the other person’s fear. Without secrets, I would be completely destitute.

Once, I heard Mrs. Chang attempt to defend me. “Listen. It wasn’t just one or two women who went insane during the war. We all saw mothers trying to breastfeed their dead babies and maimed little girls crawling around looking for their younger siblings. I remember an old woman in Hungnam who embraced her disabled son while they leaped off the wharf to their deaths.” She implied that I was just one of countless women who had gone crazy during the war, and that I should be accepted as such. But even Mrs. Chang, who considers herself my guardian, most certainly doesn’t like me. I’ve been brought into her care because the intended recipients of her maternal instinct have died. Maternal instinct—I’ve never had it, but I wonder if it’s similar to opium. You can try to stay away from it your entire life, but it would be incredibly hard to quit if you’ve tasted it. That is what maternal instinct is—grand and powerful and far-reaching. During the war the most heartbreaking scenes were of mothers standing next to their dead children. Maybe not. The most heartbreaking scenes during the war can’t be described in words.

In any case, perhaps confusing me for her daughter, Mrs. Chang meddles constantly in my affairs. It goes without saying that she has a litany of complaints. She looks at me with contempt. After all, I rinse my hair with beer, a tip I learned from an actual prostitute. That is certainly something to look down on, but I do have my reasons. My hair is completely gray. One autumn long ago, I grew old in the span of a single day. Afterward my hair never returned to its true color. My unsightly hair has the texture of rusted rope, but I’m satisfied with it for the time being. Mrs. Chang also despises my vulgar clothes, unbefitting, she says, of my status as an educated woman. But none of the things I’d learned academically helped me in the decisive moment of my life; my intelligence and talents, though not that deep or superior, were actually what entrapped me. Nor does Mrs. Chang think highly of my personality. She says I am haughty, which she thinks is why I don’t like people, but she’s not entirely correct. The truth is that I’m too broken. In any case, she cares for me in her heartless way and keeps me near. Even stranger is that I can’t seem to leave her, though I too look down on her. Our unusual connection yokes us together despite everything. She probably feels the sharp wind of Hungnam when she sees my bloodless cheeks. My pale forehead would remind her of the Koje Island refugee camp, where we were doused with anti-lice DDT powder as we sat on the dirt floor. Though we never meant to, we have somehow lived our lives together. We have a special bond, like all those who experienced war. We shared times of life and death. And she clearly remembers my triumphs and my defeats.

I triumphed by surviving but ended up surrendering; I tried to hang myself in the refugee camp, an act so shocking it cemented my reputation as a crazy woman. Mrs. Chang happened to walk by and pulled me down with her strong arms and brought me back to my senses with her vulgar cursing. Why did I want to plunge into death after I’d survived bombings and massacres? I still don’t understand my reasons, but Mrs. Chang is certain in her own conjectures and stays by my side to watch over me. Hers is not the gaze of an older woman looking compassionately at a younger one. It’s the sad ache of a woman who is well-versed in misfortune, feeling sympathy for a woman who is still uncomfortable with tragedy. If there’s a truth I’ve learned over the last few years, it’s that a woman’s strength comes not from age but from misfortune. I want to be exempted from this truth. I have earned the right to be strong but now I do not want this strength. A woman becomes lonely the moment she realizes her strength. As loneliness is altogether too banal, for the moment I would like to politely decline.

I leave Chayu Market and head towards Myong-dong.

Wind enters through my parted lips, cold enough to form a layer of thin ice on my tongue. I swirl my tongue around and swallow it. Having passed through the desolate city, the wind has an odd candy sweetness to it. Not many people are out on the street and for that I am grateful.

A streetcar crammed with people pulls up as I stand at the traffic circle in front of Bank of Korea. Teeming with black heads, the car resembles a lunch box filled with black beans cooked in soy sauce. Everyone is expressionless, making me wonder why we even have eyes, noses, or mouths. I stare at those stone-faced people and gradually their features begin to disappear, leaving behind only their black hair. I can’t breathe. I feel dizzy. I close my eyes and turn away. The streetcar continues down the street and I let out a sigh, as though freed from a corset. I look around to see if anyone has seen my reaction. There is no cure for this. Even after all this time, I have a physical reaction in a mass of people. It harms my dignity; shuddering like a pissing dog every time I find myself in the middle of a crowd doesn’t fit the independent life I seek. People who’d witnessed my reaction spread the rumor that I had gone insane. They might expect that I would make profuse apologies but I refuse to do so.

I walk past the Central Post Office and spot a hunchback child sitting out front. Wrapped in a ragged blanket and wearing a newspaper-thin skirt, she is begging. She scratches a spoon on an empty brass bowl and emits a sound more desperate than the Lord’s Prayer. Could that child become a woman without being violated? That’s what I worry about. I turn away, unable to meet her gaze. I hear a baby’s cry. My head snaps around. The girl’s rounded spine straightens and a head pops up. She had her infant sibling on her back all along. The baby wails, arching its neck, and the girl looks up at the sky and mumbles, too weak to soothe it. Her dark eyes reflect nothing. She may never have even heard of such unrealistic concepts as hopes or dreams. I rummage through my bag and find a broken Hershey’s bar. I toss it at the girl and rush off. The chocolate won’t solve the child’s hunger; it’ll just introduce her to the easy temptation of sweetness. Unable to forget that chocolaty taste, she will continue on the streets. That is the purpose of a Hershey’s bar, which befriends both soldiers and children during war.

“Did you read Mrs. Freedom yesterday?” Yu-ja asks, heating steel chopsticks in the flame of the stove. “What do you think will happen next? Don’t you think Professor Chang’s wife will sleep with her next-door neighbor? I’m positive she will. Isn’t the very term ‘next-door neighbor’ so seductive? I’d say it straddles the line between melodrama and erotica.”

Yu-ja works as a receptionist at Myong-dong Clinic, which is set back from the bustling main thoroughfare. That may be why it’s never too busy when I stop by to see her. It’s a dull place for a vivacious girl like Yu-ja, who seems always to be moving to the music of a dance hall band.

“That’s all anyone talks about these days,” I say. “As if they don’t know how contradictory the two words are together—Mrs. and Freedom.”

Seoul Sinmun, which is publishing Mrs. Freedom as a serial, is open on Yu-ja’s desk. It’s the talk of the town. Yu-ja reads each installment passionately. In fact, she rereads it several times a day.

“That old-maid intellectual sarcasm of yours! You know men hate that, right?” Yu-ja counts slowly to twenty, twirling her bangs around the heated chopstick. When she takes the chopstick out, her hair emerges not as Jean Harlow’s Hollywood wave but as a sad, limp curl like a strand of partially rehydrated seaweed. To make up for her failed attempt at a wave, Yu-ja pats another layer of Coty powder on her face. She tugs on a new skirt, struggling on the examination table. She’s quite alluring. When I look at her round, peach-like face, I can’t believe she signed up to be a cadet nurse in the war.

In order to secure a place on an evacuation train during the Third Battle of Seoul, Yu-ja had run to the recruiting district headquarters inside the Tonhwamun Gate at Changdokgung Palace, having seen a recruitment ad for nurse officers in the paper. She was ordered to assemble at Yongdungpo Station that same day, and she dashed across the frozen Han River just as the last train evacuating the war wounded was about to leave. As soon as she boarded, Yu-ja was tasked with helping soldiers to go to the bathroom and spent the next few days working incessantly on that train, which traveled only at night. One early morning, as the train pulled into some countryside station, Yu-ja was using the dawn light coming through the window to search for and eat the bits of rice the patients had dropped, and in that moment she truly knew despair. Once in Pusan, Yu-ja put on a US Army work uniform and even went through basic training, but, worried about her family, gave up her dream of becoming a cadet nurse. Yu-ja experienced her own hardships during those years; not until fairly recently has she been able to powder her face so liberally. I understand why she’s rushing around with her womanhood in full bloom. A flower’s lifespan is ten days but a woman’s spring is even shorter. Many a spring died during the war. The mere fact that she survived has given Yu-ja the right to bloom fully.

“Are you going back to the officers’ club tonight? Your dance steps aren’t up to standard,” I tease.

Yu-ja smiles confidently. “You’re going to want to buy me a beer when you hear what I have to tell you. Ready for this? Remember I told you that one of our patients is married to the chairman of the Taegu School Foundation? Her family operates several orphanages and daycare centers. I mentioned Chong-nim and she said she would ask around. I think she has some news for us!”

Chong-nim. My mouth falls open and my breathing grows shallow.

“Go ahead and close your mouth,” Yu-ja says teasingly. “How do you earn a living when you act like this?” Yu-ja is hard on me and at the same time worries about me. I wouldn’t let anyone else do that but I humbly allow her. Mrs. Chang saved me from death while Yu-ja took me in when I went crazy. All of that happened in Pusan—goddamn Pusan, that hellish temporary wartime capital of South Korea. Each time Yongdo Bridge drew open, stabbing at the sky like the gates to hell, I believed that an enraged Earth had finally churned itself upside down to proclaim complete disaster. The streets were lined with shacks built out of ration boxes and the smell of burning fuel mixed with the stench of shit. I spent days lying like a corpse in a tiny room as rain dripped through the roof reinforced with military-issue raincoats. I want to eat Japanese buckwheat noodles, I told anyone who would listen. Yu-ja would empty my chamber pot when she got home from work and snap, Please get a grip on yourself. Why are you acting like this? Why? I could understand Yu-ja’s frustration. To her, it was unimaginable that I could have a tragic future. I knew Yu-ja, who was a few years younger, from the church I attended for a bit after liberation. We were never close but she always showed an interest in me. When I was transported to a hospital in Pusan, Yu-ja was working there as a nursing assistant. I didn’t recognize her; I was at my worst, unable to utter my own name, but Yu-ja remembered even my most trivial habits. I had been the object of envy to young Yu-ja, having studied art in Ueno, Tokyo, and worked for the American military government. She remembered me as quite the mysterious and alluring role model. It might have been because I was harboring the most daring yet ordinary secret a young woman could have—being in love with a married man. That was a long time ago, when I was still called Kim Ae-sun.

And now she is talking about Chong-nim. Her name makes me alert. I’ve been looking for that girl for the last three years, that child with whom I don’t share even a drop of blood, the five-year-old who grabbed my hand trustingly as we escaped Hungnam amid ten thousand screaming refugees, where we would have died if we hadn’t managed to slip onto the ship. If I were to write about my escape I would dedicate the story to her. To the girl who would be nine by now, her nose cute and flat and her teeth bucked, from Huichon of Chagang Province. Her hopes were small and hot, like the still-beating heart of a bird. Her will to survive roused me from Hungnam and miraculously got us on the Ocean Odyssey headed to Pusan. It was December 24, 1950. The night of Christmas Eve was more miraculous and longer than any night in Bethlehem. I wouldn’t have lost her if I hadn’t acted like a stupid idiot. She disappeared as I lay in the refugee camp infirmary, conversing with ghosts. She became one of many war orphans, their bellies distended and their hair cut short, buried in the heartless world.

“The orphanage is somewhere in Pohang,” continues Yu-ja. “There’s a nine-year-old girl, and she came from Hungnam around the time you did. I heard she has the watch you talked about. What other orphan would own an engraved Citizen pocket watch?”

My—no, his—watch that I gave to her, which she tucked in the innermost pocket of her clothes. It had been our only keepsake. That small watch is probably ticking away with difficulty just like me, cherishing time that can’t be turned back.

“Where is it? Where do we need to go?” I spring to my feet.

Yu-ja tries to calm me down. “I don’t know all the details. I’m supposed to meet her this evening at the dance hall. Why don’t you come with me? There are too many orphans, and the records are so spotty it’s hard to find them. The lady managed to get in touch with a nun who saw a girl that fits her description somewhere in Pohang.”

But Yu-ja is unable to convince me to wait and has to run after me without putting the finishing touches to her makeup. Next to fresh, fashionable Yu-ja I look even more grotesque. Yu-ja is a young female cat who’s just learned to twirl her tail, and I’m an old, molting feline who can barely remember the last time she was in heat. I’m not yet thirty but I feel like an old hag who has forgotten everything.

We go down the stairs. Yu-ja tugs my arm at the entrance to the obstetrics clinic; a young girl is squatting in the cold hallway, wearing a quilted skirt, a man’s maroon sweater, and a black woolen scarf wound around her face. Her gaze is feral, sad, and cold, a dizzy tangle of defensiveness and aggression. Yu-ja pulls me along. “She’s a maid for some rich family in Namsan,” she whispers. “Did you hear what happened? The master of the house raped her and now she’s pregnant. Then he and his wife accused her of seducing him, beat her, and threw her out. Apparently she has eight younger siblings back home. She was here yesterday too, asking for help to get rid of it. So many maids are in her situation. I feel bad for them. They try to get rid of it by taking quinine pills—it’s so dangerous.”

We step into the street and the wind delivers a hard slap. The maid’s rage and despair scatter in the wind. This city poisons girls and women, young and old. Girls with tragic fates are merely a small segment of the people who make up the city. The light they emit in order to hide their shame turns the city even more dazzling at night. The streetlights go on and the light seeps into my heart. It has taken in yet another unforgettable gaze.

It’s still early but the dance hall is crowded.

The dancers are gyrating enthusiastically, as though it’s the last dance of the night. This is a sacred place for the wild women of these postwar times, these women who rightfully intimidate men. Of course, men dance too, but women own this place. A rainbow of velour skirts and nylon dresses twirl like flower petals. There are café madams, owners of downtown boutiques, restaurateurs, dollar exchangers, rich war widows, wives of high-level officials, teachers, concubines, college students—I am taken aback that these are all women who have lived through the war. Maybe they hung their grief and pain on the heavy, sparkling chandelier. I’m jealous of these women whose desire to dance is so intense, who look as if they would keep dancing no matter what. Having learned the futility of life, they move lightly without any regrets. I can’t do that. My breath catches in my throat as I watch them dance, skin to skin. The sight calls to mind images of the masses, moving with a single purpose. As I stand there, dazed, Yu-ja pushes me towards a table in the middle of the room. The chairman’s wife and the wives of business and political leaders, all in fox stoles, greet us.

“I understand you’re fluent in English and you studied in Tokyo,” the chairman’s wife says. “My son is preparing to study in America. I would ask you to tutor him if you weren’t a woman.” She laughs. The other wives look askance at my whorish hair and my tattered black lace gloves. By the time their eyes settle on my worn stockings, they are concluding I am not who I purport to be.

I cut to the chase. “When can I see Chong-nim?”

The chairman’s wife gestures at me to be patient and pours me a beer. “The nun I met at the single mothers’ home told me about a girl who fits that description. Something about a pocket watch? I put in a special request to find her. You can go to this address and ask for Sister Chong Sophia.” She smiles as she hands me a card.

I bow in gratitude. She takes my hand. She’s drunk. Her eyes betray a hollow elegance unique to a woman of leisure.

Meanwhile, Yu-ja is craning to find someone. “Look who’s here!” she says, clapping and springing to her feet.

The band is now playing a waltz. Perfume ripples and crests against the wall. Beyond the couples moving off the dance floor is Park Ku-yong, who scans the room until he spots Yu-ja. He waves and comes towards us. Alarmed, I try to duck under the table as Yu-ja grabs me and pulls me up. Ku-yong is wearing a black, faded university uniform and an embarrassed expression, as if he is fully aware that he doesn’t quite belong. His footsteps, however, are as assured as ever, obliterating the rhythm of the waltz as he walks towards us. I glare at Yu-ja and pinch her hand.

At our table, Ku-yong bows and the women welcome the opportunity to tease me. “Oh, you must be Miss Alice’s boyfriend!”

Ku-yong smiles in embarrassment. I can’t in good conscience make him stand there like this so I quickly say my goodbyes and take my leave. Yu-ja laughs and wishes me luck. She’s certain that this man has feelings for me. She might be right, but I haven’t confirmed it. I want to avoid the chronic mistake of a lonely woman, confusing a man’s kindness for love. Any special feelings he might have for me are more likely sympathy.

“You came all this way but you’re not even going to dance?” This is Ku-yong’s attempt at a joke, but I look away.

I can’t dance with him. You don’t dance with a man who regards you with sympathy. You can drink with him and even sleep with him, but you can’t dance with him. That would be insulting to the beautiful music and the sparkling chandelier.

Ku-yong and I walk apart from each other like an old-fashioned couple who keep a decorous distance in public.

Worried that his gaze might land on my body somewhere, I shiver for no reason at all. “What are you doing here?”

“I was at Yu-ja’s clinic last week with an unwell coworker. She told me I would see you today if I came by. I’m glad I did.”

I look down at his shadow stretched out next to me. He’s probably not eating well either but his shadow is sturdy. His interior is likely hollow, though. What once filled his soul has probably leaked away. I know because that’s what happened to me. We were artists once, but now we barely remember how to hold a pencil. I make a living with my clumsy English skills while he is stuck doing manual labor at the US military ammunition depot in Taepyongno.

The silence makes me uneasy. “Marilyn Monroe is coming to Korea,” I blurt out. It’s never advantageous to talk about a prettier woman than oneself but I am curious about his reaction.

Ku-yong widens his already big eyes and raises his arms in a silent cheer. That’s the power of Marilyn. “Can you believe she’s married? You’ll have to find someone yourself, don’t you think?” He glances at me.

I’m charmed by his effort to link Marilyn’s life to mine. I let out a laugh. “Gentlemen prefer blondes, which you know I’m not.” No gentleman likes prematurely gray hair washed with beer. But I also can’t stand gentlemen. The two men I loved were gentlemen and they both disguised their true selves with well-tailored suits and nice manners. The man who ruins a young lady’s reputation is often a gentleman who walks her home at night.

“Alice, have you been drawing?” Ku-yong asks suddenly.

I glance up at him. Mediocre people like us don’t dare talk about war or art, the great subjects of humanity. If there is anything we learned, it’s that you avoid war and art to the best of your ability if you want to live your life to its natural end. “No. And you?”

“I’ve started to. On postcards this big.” He shows me with his hands. “I draw the stream I can see from my room. I don’t have interesting ideas like before; I just draw what I see—reality.”

His answer lands like a punch. I was certain he wouldn’t be drawing either. I turn to look at him. He rubs his peanut-shaped face with his wool gloves, his white breath hanging in the air. He resembles his own cartoon character. As I was familiar with his cartoons that ran in newspapers and magazines, I recognized him instantly when I met him for the first time. Ku-yong, who studied art in Japan, wasn’t famous, but he enjoyed a quiet fan base of passionately devoted readers—I was one of them. Truth Seeker, the main character of his editorial cartoons, was a sly and honest thinker, just like him, and Dandy Boy, the main character of the adventure cartoon serialized in a youth magazine, was a stubborn dreamer whose future seemed precarious, just like his. He was the rare artist who loved his work without being taken over by it. It’s entirely because of the war that someone like him now does odd jobs wearing cotton work gloves instead of handling sharp pen nibs.

The war broke out during a brutal, broiling summer. Every day until I crawled home, exhausted, in the evening, I was shut inside a small room, drawing dozens of Stalin portraits for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, while downstairs Ku-yong drew propaganda posters exhorting the North Korean People’s Army to launch a full-scale offensive. We were two loyal dogs with a talent for drawing; I was the female on the verge of starving to death, repenting my consorting with American imperialists, and he was the quiet male bringing me balls of rice and water. I didn’t feel well and spilled as many tears as I shed drops of sweat. People think Communism was what treated me poorly, but in reality it was myself. I would drink from the cup of water I washed my brushes in as I willed the awful summer to pass. At that point I didn’t know the half of it. When the recapture of Seoul by the southern forces was imminent, Ku-yong was taken north before I was, but managed to make a dramatic escape and reach safety. Eventually, the South determined that he had collaborated with the enemy and took him into custody. His talents were highly valued, however, and he was thus assigned to the psychology unit of the army headquarters and began to draw cartoons for the Ministry of National Defense. Whereas he once conveyed the grand news of victory for the People’s Army, he now began to depict women being violated by the Chinese Communists in a new, realistic, graphic style, broadcasting the tragedy of war. Ku-yong told me later that he could smell ink even in his sleep; even fermented soybeans would smell like paint. He returned to Seoul after the South retook the capital and decided he was done with art. This decision was as logical as the laws of nature in which spring followed winter. It also revealed his respect towards his newly recovered freedom.

Last year, when I bumped into him in Chong-dong, he explained bluntly why he had stopped drawing: “You see, it’s a waste of time for me to sit inside a room all day.”

Oddly enough that comment made me feel at ease. At first, even acknowledging his existence reminded me of that demonic summer, which made me want to avoid him, but his loneliness and his reclusive tendencies pulled me in. After all he was a colleague from a wretched phase in our lives. We had both exhausted our God-given talents in this godforsaken land.

“Ae-sun—I mean, Alice—I think I’m going to make art again.”

I have nothing to say to that. I should be applauding him for starting over, for overcoming his wounds and his helplessness, but I turn away, my hands laced together. It shouldn’t be a surprise to him that I’m this ungenerous; I’m dismayed that my friend is no longer defeated or despairing. I feel instantly alone. I’m disappointed with myself.

“Shall we walk towards Chonggyechon?” he asks. “We can get something to eat on the way.”

That’s such a long, dirty walk, especially in these worn shoes. But I don’t voice my feelings. What made him change his mind? I feel as if I’ve been punched twice today: Hammett’s words to me in the office are still buzzing in my ears and now even Ku-yong is irritating me. I could make excuses and tell myself I wasn’t such a great artist anyway, but I’m enveloped by a strange guilt.

We pass Supyo Bridge and the shacks balanced on either side of Chonggyechon. Built from rough pieces of wood, the shacks appear to have been made with the remnants of Noah’s Ark. It’s as if Noah and his descendants managed to survive by eating the animals they saved. The evening is filled with the smell of food and filth, along with the sounds of clean laundry being ironed, beaten with sticks, and of babies crying. A worker cleaning his tools at a hardware store spots us and smiles slyly. We must look like pathetically destitute lovers out on a date.

Ku-yong takes me to his favorite bar. A Homecoming poster is stuck to the greasy wood-paneled wall. Clark Gable’s and Lana Turner’s nice smiles are incongruous with this place. The barmaid’s son, playing marbles in front of the furnace, greets us spiritedly and shows us to a fairly clean table. The barmaid, who was serving liquor up in the loft, quickly slips down the ladder. I must be hungrier than I realized; before the mungbean pancakes arrive at our table, I empty half a kettle of makgolli. Ku-yong keeps pouring me more. By the time he starts to irritate me, I realize I’m drunk. I loosen my grip on my cup.

“I hope great things happen for you this year,” he says, smiling and tearing a piece of pancake for me. Affection lingers in his eyes.

I’m confused. I hope he’ll stop at sympathy. Affection disarms you. I don’t want any of it. I prefer to be honestly misunderstood than insincerely understood. “You’ve somehow managed to find hope for yourself so you’re all set,” I say tartly.

He doesn’t deflate. That alone makes me feel trapped. “Ae-sun—I mean, Alice,” he begins. I can tell from his voice that he’s been considering what to say for a long time. “I hope you’ll find peace. I’ve been living the last few years like an idiot. I don’t regret it, of course, but I want to have a different life. I hope you’ll be able to forget the past, too. This isn’t you. We both know it.”

I stare resolutely at the table, refusing to meet his eye.

“Be with me. In whatever way that may be. Ae-sun—I mean, Alice …” Ku-yong isn’t even embarrassed. He’s as earnest and frank as his cartoon characters.

I must have sensed that something like this would happen. That must be why I came along. I decide to save him by putting a firm end to this ridiculous melodrama. “You can’t be with me, Ku-yong. You can’t understand my pain. Do you know why? I’ve killed. I’ve killed a child. And then I went insane and tried to kill myself. I failed at doing that so I went crazy. I’m fine now, but you never know when I’ll lose my mind again.”

The boy, who was eavesdropping, scampers off in shock. Ku-yong stares down at the floor uneasily. He doesn’t even attempt to take in what I’m saying. “Stop with the bitterness and mockery. That’s not you.”

For some reason this makes me sad. “Let go of your expectations. Don’t waste whatever remaining love you have for humanity on me.”

“You’re so frustrating, Ae-sun! Look around. People are living, they’re being strong, they’re as good as new. Why do you keep insisting on staying in the past?”

I lose my confidence for a moment. “Why do you want to take on my nightmares I don’t want to remember?” I ask. “What do you know about me, anyway? Do you remember the state I was in when we bumped into each other last year? You looked at me like you’d lost all hope for me.”

In fact, Ku-yong regarded me with shock, like a burn victim seeing himself in the mirror for the first time. Anyone else making that expression would have infuriated me, but oddly enough I stared at him with the same expression on my face.

“Don’t you remember?” I ask him. “I looked just like Seoul—hopeless, though nobody wanted to say that out loud. I was at my worst in Pusan, but I wasn’t much better back here. I tried, though. I tried to be ordinary and be one of those people. But it didn’t work for long. One day I was walking downtown and I passed the bombed-out fire station. All the windows were gone and you could see the darkness inside. It was like an enormous skull with two eye sockets. It began to laugh, its jaw juddering. I jumped onto the first streetcar that came. But it started to fill up and I was stuck among people and I couldn’t breathe and I was sweating and my ribs felt like they were breaking and I could hear a horrible noise and everything turned dark. I started to smell blood, and every time people brushed against me I felt like I was being torn to pieces. I sank down, below people’s legs. I was curled up like that on the floor, screaming for help. Do you know what they did? In order to gawk at me properly, they managed to move around in an orderly way in that overcrowded car. Watching a crazy woman is more entertaining than a fire, isn’t it? As soon as I felt people’s eyes on me, I turned mute. The heel of my shoe broke off and I was foaming at the mouth and it got all over me and nobody came to help. Finally a woman with a child on her back elbowed her way through from the end and took off the cloth that was holding her child to cover my thighs. Menstrual blood was streaming down them. I saw relief in people’s eyes, glad that they weren’t me. A few men leered, peering overtly between my legs. I accepted it then, that I always was and still am someone who makes people uncomfortable. Look at this, Ku-yong.” I show him my right hand.

He gazes sadly down at my pale hand, covered in my ripped black lace glove like a discarded fish in a dead fisherman’s net.

“Sometimes it’s hard for me to hold someone’s hand, even when they’re right in front of me. I’m still—people are still hard for me.”

Before he can take it, I withdraw my hand. I am treating this man who has feelings for me with the bare minimum of politeness. But he doesn’t realize that he’s the first person I’ve ever told any of this.

Ku-yong gazes quietly at the space vacated by my hand. He takes something out of his pocket. It’s a smudged fountain pen and a yellowed postcard. He begins to draw as if he’s alone, his pen scratching like a broom. I haven’t seen him like this in a long time, hunched forward, head down, concentrating. I stare at him, mouth agape, content to watch. He’s looking at his old pen with affection, like he’s Jesus looking at a child.

When he’s done he hands me the postcard with a smile. Fine slashes fill the paper, pouring down like shooting stars in the night sky. I laugh despite myself. He’s drawn a propaganda leaflet. And it’s me he’s drawn in it. I look funny and pitiful and cute, all at the same time. I’m wearing a dotted scarf on my head and shaking my fist, chanting slogans, and behind me is the sentence, “Alice! Build up your battle experience to rescue your compatriots!” The propaganda posters and leaflets we were forced to make during the war were fierce, coarse, and foolish. This is different. This is special. I’m intrigued, though I am hardly the type to get provoked by these things. It contains irony and pathos. This is a superlative drawing.

“Are you still—do you still care for him?” Ku-yong lobs the question he’s been wondering about. He remembers how restless and resentful I was that summer, pining by the window.

“Not him. Them,” I cruelly correct Ku-yong.

It’s a low blow to mention men I can barely remember anymore to a man who desperately wants to comfort me. The cheap, artificially carbonated liquor served by the surly barmaid burns, turning my mind blank and clear. Ku-yong’s eyes are as dark as ink as he forlornly twists the cap of his fountain pen. I feel torn and a little sorry.

Adequately tipsy like the youth we are, we head back into the night. The dark night of this city, which doesn’t yet have electricity fully restored, makes the streetcar stop seem even more desolate. Ku-yong insists he will see me home. He’s gallant for a man who’s been refused. Maybe he’s reliving the sorrow of being turned down.

“When will you get back?” he asks with concern, as though I’m going somewhere far away, although I’m just accompanying Marilyn Monroe to perform for the troops.

“It’s a four-day trip, so I should be back at the end of next week.”

Ku-yong seems so distressed that I find myself wondering if I will indeed return safely in one piece.

The streetcar barrels towards us, its headlights slicing through the darkness.

Ku-yong puts a hand on my arm. “I’d like to see you when you’re back, Ae-sun.” His gaze arrests me for a moment.

“Would you like me to say something to Marilyn for you?” I smile, but he doesn’t. The streetcar is nearing the stop but his hand is growing heavier on my arm.

He finally lets go and flashes a smile when I try to get on the streetcar. “Please convey my congratulations. And tell her that we are hoping for her happiness, for her to always be happy.”

The streetcar takes off and he waves. His wet eyes sparkle as they are swallowed by the black street.

I quickly find a seat so I don’t have to see him. But his form follows me, pasted to the window. I turn back and he’s still standing there, watching me, growing smaller. What a night. A strange night filled with memories creeping and advancing like fog. I’m not afraid of the regret and disdain settling wetly on my cheeks. I leave behind the man who is perhaps the last person to understand me. I desperately hope he won’t remember tonight as remarkable, as a night to be remembered. I hope we can all fall asleep peacefully—all of us, the beggar girl carrying her sibling on her back, the maid seeking abortion funds, lovelorn Yu-ja standing sentry at the dance hall, lonely Mrs. Chang who has to show her husband pictures of naked American women. Seoul adroitly hides its ruins in the darkness and I too disappear into it. I enter the deep blackness of the city, which has chewed and swallowed all of humanity’s beauty—the past, the tears, the blood, the lovers, the diaries, the ribbons, the book pages—in equal measure.