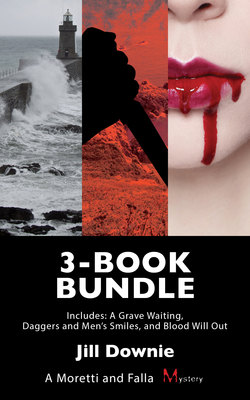

Читать книгу Moretti and Falla Mysteries 3-Book Bundle - Jill Downie - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Five

ОглавлениеHer heart was beating hard enough to burst the thin cotton of her shirt — as hard as the blows she would have liked to have given him, to wipe the taunting smile off her husband’s face. When Sydney Tremaine found herself in the corridor outside the marchesa’s sitting room, she was shaking with suppressed rage, the humiliation of being insulted in front of the civilized and quiet-spoken detective inspector. If they had been on their own, she would have picked up the nearest blunt object — anything that would have served as a missile — and thrown it at Gil.

What should she do now? Wait meekly around until the interview was over, babysit Gil for the remainder of the day, as she usually did, and then return to their hotel suite to scream and shout and rant at each other? Or to drink too much, have sex if Gil was not too drunk, and go to bed?

The prospect was appalling. Sydney leaned against the wall and closed her eyes.

When she opened them again, she saw a figure at the end of the corridor. It was the woman who had arrived on the motorbike, the woman she had seen running along the cliff path — and whom she had told the detective inspector she didn’t know.

“Wait!” Sydney started to run toward her.

The woman stood and waited, her hands on her hips. As Sydney got closer, she saw she was smiling.

“You are Sydney Tremaine, the ballerina.”

“Ex-ballerina. You are the jogger I saw on the cliff path near the Héritage Hotel.”

One finely pencilled eyebrow was raised. “I don’t jog. I run. Yes. Giulia Vannoni.”

“You didn’t hear me call out?”

“I hear nothing with my iPod. Not the birds, not the sea, nothing.”

She extended her hand and Sydney took it.

“Someone threw a dagger at my husband at about the same time.”

“So they tell me. And missed. If it had been me, cara, you would be wearing black right now.”

Sydney saw that Giulia Vannoni had green eyes but, unlike her own, they were long and slightly slanted, and they were looking challengingly at her.

“Why were you standing outside my aunt’s study?” she asked. “Are you looking for her?”

“No. The detective inspector is questioning my husband. I — left. I didn’t tell him that I saw you. I’m not sure why.”

“Ah? Perhaps you hope I will hit my target next time?”

The pent-up anger of the past few minutes — of the past few days, weeks, months — burst from Sydney Tremaine in a flood of tears. “Christ! No. Yes. I don’t know!”

“Hey!”

Giulia Vannoni did not put her arms about her, pat her on the shoulder, talk in soothing tones. She took Sydney by the elbow and steered her toward the foyer that led out on to the terrace. “I’ve got to move my bike. Come on.”

The Ducati stood where Giulia had left it, with a small group of admirers around it — English and American crew members, and some Italian macchinisti, brought in to handle the equipment rented from Rome.

“Hey boys — don’t touch!”

“The bike you mean, Signorina?”

Puzzled, Sydney watched Giulia Vannoni explode. Most Italian women she knew enjoyed such remarks, or dismissed them with a shrug or a humorous comment. But this Amazon turned on the man with a burst of such rapid Italian that Sydney missed most of the meaning, although the language was pungent enough to make the joker flinch. The crowd quietly withdrew.

“My new baby. Superbike eleven ninety-eight, special edition. Beautiful lines, great control.” Giulia was smiling again.

“I like the logo.”

“Pretty, isn’t it? It is the emblem of many of my friends in Florence.” Giulia’s smile grew wider. “Like a ride?”

Sydney indicated the intricately painted gold and black helmet with its dark visor hanging on the curved handlebar. “I don’t have one of those,” she said.

“We’ll find one. Come.”

Sydney found herself following Giulia and the Ducati around the side of the manor, along the path that had led to what she now thought of as her point of no return. One thing was certain: wherever the path and Giulia Vannoni were now taking her could be no more disturbing than the scene of violent death on the terrace. The shock of seeing Toni Albarosa with a dagger in his chest — a dagger that looked distressingly like the one that had landed on the hotel patio at Gil’s feet — seemed to have deprived her of rational thought, and she was content to have this complete stranger decide what she should do next.

In an area to one side of the main courtyard, which was principally used for vehicles in the movie, were parked the hired limousines and the various cars, bikes, and motorbikes that belonged to the crew. Giulia propped up the Ducati and made for a line of motorbikes, sorting through any helmets that had been left as if she were in a store.

“No, troppo grande — mmm, no, brutto — si!” Triumphantly she held up a neat metallic black helmet with bronze highlights. “Bello, perfetto — from Roberto Stavrini, like mine. It will go with your hair.”

“But I can’t —”

But she could. The helmet was placed on her head, the strap fastened beneath her chin.

“Eh — Cosimo!”

Giulia called out to a tall bearded man crossing the courtyard, and Sydney recognized the art director, Cosimo Del Grano, who was on his way to the building where the costumes were stored. “Lend us your jacket.”

“Darling, but why?” he protested, as Giulia started to remove his heavy denim jacket, kissing him profusely as she did so.

“Because, because, caro — I’ll get it back to you.”

As the two talked and laughed, Sydney began to put together the pieces of the past few minutes: the jibe by the crew member and Giulia’s reaction, the way Cosimo spoke to this woman, even the emblem on the Ducati. Could it be —?

The jacket was huge on her. Sydney rolled up the sleeves and hauled it across her body. She could feel her heartbeat quieting, the delicious irony of the situation easing her sense of desolation. It looked as if the whirligig of time was bringing in a revenge far sweeter than she herself could possibly have dreamed up, in her wildest and cruellest imaginings.

“Come on, Sydney,” said Giulia Vannoni. “Let’s go.”

And go they did. Heart in mouth at first, Sydney felt every muscle in her body stiffen as they roared away, the wind blowing through her completely inadequate sandals, the Ducati accelerating rapidly as Giulia put it through its paces, winding along the lanes to the south of the Manoir Ste. Madeleine, smooth as the feel of Giulia’s soft leather jacket beneath her hands. Gradually, Sydney found her own movements blending with Giulia’s, much as she had learned to move with another dancer in a pas de deux, relying on the strength and expertise of her partner.

They seemed to be heading for the southern coastline of the island. In spite of their introductory tour, Sydney was vague about the geography of Guernsey, but she knew that this coastline — unlike the flatter, gentler western coastline where much of the filming would take place and where many of the wartime installations were to be found — was craggy and spectacular. Wild and beautiful, its cliffs and coves were breathtaking enough to have attracted the painter Renoir on a visit to the island. They turned yet another corner in a small, winding lane and Sydney saw a sliver of milky blue horizon beyond a cleft in the pine-covered slopes. Sydney felt herself slip toward Giulia as the Ducati descended a steep slope between the trees.

“See?” Giulia called over her shoulder, her words blown back by the wind. “Mio castello.”

Giulia’s castle, set high above the sea, was one of the eighteenth-century Martello towers, built to protect the island against Napoleonic invasion. This one seemed to have been modified, because on top of the familiar circular construction with its tiny slit windows, was what appeared to be another storey, with wider windows, still elongated in shape. There was a stone wall encrusted with plants around the perimeter of a grassy enclosure, with a solid-looking gate set in it. Giulia brought the Ducati to a halt by the gate, and got off the bike.

“Here, let me give you a hand. I’ll unlock this and we’ll walk from here.”

“Your castle? I wouldn’t have thought they allowed anyone to buy one of these,” said Sydney, removing her purloined helmet. She was grateful for the heavy jacket. They were high up, close to the edge of the cliff, and the wind was strong.

“Yes, it’s mine. There are only one or two of these on private land — there’s one out at L’Ancresse in the north of the island, I’m told — and I was lucky enough to be staying with my aunt when this one came on the market.”

“The marchesa is your aunt?”

“She is.”

Giulia pulled the Ducati through the gate, which she relocked. “Robbery is not such a problem here — it’s the sightseers and nosey small ragazzi I want to keep away from the place,” she said.

For a moment, Sydney hesitated. Ahead of her, the Martello tower loomed, grey, cold and forbidding, like something out of a tale by Grimm. No attempt at decoration had been made to the exterior, and the area around it was unkempt, rough beneath her feet with exposed rock and long grasses. Above her head a flock of gulls wheeled with their hideous shriek. Ahead of her she saw that Giulia had unlocked the door of the tower and was pushing the Ducati inside.

Well, she thought. You’ve done dumber things in your life, woman. And walked toward Giulia Vannoni.

“Welcome,” said Giulia, “to my castello isola.”

As Sydney stepped across the threshold, Giulia flicked a light switch by the door.

Sydney gasped.

Where the outside had been bleak and forbidding, the interior was warm, glowing with colour, ablaze with oranges, ruby reds, carmines, emerald and aqua, the glowing blue of stained-glass windows or Victorian enamels. Giulia was laughing as she flicked down the Ducati’s stand, leaving it on a terrazzoed area by the door.

“That look of surprise on your face — you expected gloomy grey and black bleakness — no?”

“Yes. This is like — a secret garden.”

“That is nice. I am away so much I do not want those beyond the walls to guess at what lies inside. The lady at L’Ancresse has a picture window where there once was a gun, but no landscaping, no tearing out of these narrow slits for me. I make my own light. Always have done, cara. I like to feel — protected.”

Giulia’s secret garden was contained in one circular room, with an iron circular staircase curling up close to one of the walls, its railings in ferro battuto, the spectacular wrought iron of Tuscany. The harsh stone of the round walls was largely hidden and softened by bronze silk curtains that had been used as an undulating backdrop, like an extra frame, for the paintings — most of them abstract, but again using the deep, glowing palette of their setting. Opposite the door through which they had entered, against a black wall — the one sombre note in the room — stood a bronze sculpture of a woman, arms raised as if she were about to dive on to the pale cinnamon terrazzo around the white translucent cube on which she stood, frozen in time.

I make my own light, Giulia had said, and it was the lighting that created the magic of her secret garden. Sconces in burnished metal mounted on the walls and standing on slender poles gave the feeling of candlelight to the space, while above their heads glittered a spectacular eighteenth-century Venetian chandelier.

“Where do you get the power from?” Sydney asked. “That’s a practical question, not a philosophical one.”

Giulia laughed. “I have a generator. The Germans used this place during the war. The bigger problem was water, but there once was a house on the site, and there is a good well. Another practical question — are you hungry?”

“Starving. My last meal was at about five o’clock this morning.”

“Me too. Let us pour ourselves some wine and get something to eat. My kitchen, such as it is, is over here, by the lovely lady.”

To the right of the sculpture was a small space semi-concealed by a screen made of the same material as the translucent cube. Sydney stepped on to the carpet that covered most of the floor.

Beneath her feet rode a knight — from the red cross on his shield, it appeared to be St. George — a deep blue surcoat over his silver armour. To one side of him stood a slender maiden, hands clasped in prayer over her deep pink dress. At her feet roared an emerald dragon in his death throes, his elegant ivory throat pierced by a sword — or a stiletto, or a dagger, since only the elaborately decorated hilt protruded.

“This is —” What was there to say? Coincidence? An omen? Sydney was at a loss for words.

“Spettacolare, no? I had it specially woven for me. I so love the legend — the king’s daughter sacrificed to the dragon that threatened the kingdom, and the knight who saves her.”

“Do you believe in knights on white horses, Giulia?” Leave the other alone, she thought. For now.

“That save us from others, or ourselves, you mean? No. But, see, his horse is chestnut. I asked for that. And above his head an angel — them, I believe in. Sometimes. Come, I’m too hungry for all this. We’ll talk while I cook.”

The small area behind the screen contained four burners set in an olive green ceramic counter, some wall storage, a small fridge, and two bar stools. Giulia patted one as she passed.

“Sit down. We’ll start with some Brunello di Montalcino.”

The wine went straight to her head, courtesy of her empty stomach. It felt good. “How often are you here?” Sydney asked.

“It depends. As you probably know, my family are in vino e olio. The olio is my baby. By the way, don’t feel too sorry for Anna, Toni’s wife.”

Giulia made no attempt to explain her remark, and Sydney did not ask. Married to a man like Gilbert Ensor, she needed no further elaboration.

The wine was outstanding, filling Sydney’s head with a humming sensation and the ability to ask the questions she most wanted to ask.

“Giulia, tell me about the symbol on your bike.”

“It is the symbol in Florence for the gay and lesbian community. Does that bother you?”

“No.”

Any worries Sydney might have had nothing to do with the sexual preference of her companion; in the world of dance she had worked closely with people whose tastes and orientation were frequently far from what some sections of society considered the norm.

“Besides,” said Giulia, “I am celibate for a little while.”

“Why?”

“Because it makes life simpler.”

There was no disputing that statement, and Sydney had other, pressing questions she wanted to ask.

“Is it a coincidence that you were running past the Héritage Hotel just as a dagger was thrown onto our patio and that, woven into the rug on the floor of your castello, is the representation of violent death by a dagger, or a sword, with a decorated hilt?”

“Coincidence, perhaps — I think your husband is a bit of a dragon himself, no? Planned, perhaps. A warning, maybe.” Giulia was taking eggs out of the fridge as she spoke and, although Sydney could not see her face, her voice was calm and unconcerned. “I often run on the cliffs in that area, and many people know that. Your hotel is only about two or three miles from here to the east of us, around the point, and there are cliff paths all the way. I am — easily noticeable.”

“That’s true. So if it wasn’t you, Giulia, then who?”

With her back to Sydney, Giulia shrugged her powerful shoulders. “Someone is saying something — what they are saying I don’t know. But take care, Sydney, because whoever they are, they are killing anyone who stands in their way — or gets in their way.”

“Gets in the way of what?’

“Who knows? That, as you Americans say, is the sixty-four-thousand-dollar question.”

Even the sweet numbness brought on by the wine had not removed the image of Toni Albarosa, the haft of the dagger protruding from his chest. Sydney shuddered. “Let’s change the subject. What are you cooking? It smells delicious.”

“Frittata, this one with some carciofi — artichoke hearts. Something simple. It is how I live here.” Giulia’s smile was back, her mood sunny again.

“You are from Florence?”

“Yes. You know the city?”

“Not very well. I find it — well, gloomy, almost scary, in some way.”

“I can understand. A city of men, Firenze bizarra — Michelangelo, Leonardo, Brunelleschi — men who had little time for women. It’s a city that turns its back on the stranger like you who passes in the street. Like mio castello, it hides pretty loggias, hidden courtyards, secret gardens behind ugly grey walls.”

It was in Giulia Vannoni’s grey Martello tower, on an island off the coast of France, sitting at a marble-topped table eating frittata and drinking Aperol, the honey-coloured aperitif of Florence, that Sydney Tremaine began to believe once more in happiness — as bizarre and unlikely a time and place as any, in which to believe in such a thing again.

“Come on now, Sydney!” Giulia sprang to her feet. “We go out on the town.”

“Is that possible?”

“Of course! You don’t know this place any better than you know Florence, do you?”

“But I think I should be getting back to the hotel.”

“The night has hardly begun, cara. Why not — how do you say it? — get hung for a sheep as lamb, no?”

“Oh, why not!”

Light-headed with wine and good companionship. Sydney threw caution out the Martello tower window. Go on, she thought, let Gil feel what I myself have felt, so many times.

“I am hardly dressed to go out on the town.”

“Here, anything goes. But I’ll lend you something that is more fun. You won’t be able to use my pants with that ballerina hip span of yours, but — let’s see.”

Giulia started up the circular staircase with her easy, powerful stride, and Sydney followed her. The staircase opened directly into a bedroom, as different as it could be from the lower level. The wider windows let in more natural light from outside, but that was not the only difference. The decor here was spare to the point of sterility, with a simply designed bed in a beechwood frame, a pristine white bedcover, a matching bedside table, chair, and dresser with the same clean lines. There were curved, sliding doors set into the wall, and a walled-off section of another wall presumably concealed a bathroom of some sort.

“This floor,” said Giulia, “was added by the Nazis when they occupied the island — I think there is one other tower like this. I had the floor strengthened, and the walls covered with the wood panels you see, more for warmth than for any other reason.”

“It’s so different from downstairs.” said Sydney.

“I sleep better in monastic surroundings,” Giulia replied, without a glimmer of humour in her voice or on her face. “In that city of mine you do not understand, it took until the fourteenth century for women to be allowed to read — unless they were nuns.” Before Sydney could think of an appropriate response, Giulia went over to the sliding doors and pulled them open.

The contrast with the spare, colourless room was startling. Scarlets, silver, golds, echoes of the riches below dazzled Sydney’s eyes, cooled by the monochromes around her.

“I love clothes,” said Giulia. “I love Versace, Gucci. Sexy, dangerous. My leather jacket is Gucci and so are these. I’ll wear them tonight.” She pulled out a pair of jeans that glittered with dozens of tiny beaded squares, with fringes of silk scattered over the blue denim. “Long ago, there was a wise woman whose home was in the portico of Santissima Annunziata — a street woman, who sewed pretty patches on her clothes. I think of her surviving con eleganza when I wear these.”

“So Italian,” said Sydney, “and yet, didn’t an American once design for Gucci?”

“E vero. Such a small world — that can make things so dangerous.”

Giulia Vannoni retreated for a moment into a mood that appeared to have come out of nowhere. Her warning came back to Sydney. Someone is saying something — what they are saying, I don’t know.

She knows, she thought. Or she knows far more than she is telling me.

“Try this.” Giulia held out a slippery satin shirt in a luminous apple green. “This is Gucci also. It feels wonderful on the skin and is perfect with your colouring.” She pointed to the cubicle. “You can use my little bathroom, if you wish. And here —” From the dresser she pulled a pair of black spandex tights. “These’ll fit. Roll up the legs and your mules will go perfectly.”

The cubicle contained an updated version of a hip bath, a toilet, a small mirror, and a tiny hand basin. As she started to change into her new clothes, Sydney heard Giulia going down the iron staircase. By the time she came back into the bedroom, Giulia was waiting for her, wearing a blue and grey striped bustier with the bespangled jeans.

“Meravigliosa!”

“Grazie — you, too.”

As they returned to the floor below, Sydney’s attention was caught by a heraldic device she had not noticed before, hanging high up on the wall near the stairs in an area shielded from the brilliant light of the chandelier. It was a shield, divided into quarters, each with its own device. In the bottom right-hand quarter was a hand, the wrist encased in chain mail, holding a dagger — a dagger with an elaborately decorated hasp. Sydney stopped in her tracks.

“Giulia —”

Giulia Vannoni looked back up from below. Her glance followed Sydney’s eyes.

“You have a dagger very like the one that killed Toni on your family coat of arms — I presume that’s what this is.”

“Yes. The shield is on every bottle of olive oil we sell.”

“So, Giulia —” Sydney sat down on one of the iron steps. “— what’s going on? Is this some extremist group? Is it the Mafia? Is this an attack on your family and, if so, how does my husband fit into this?”

Giulia held out her hand. “Come,” she said. “I have something to give you.”

She pulled Sydney to her feet, then went over to a small desk near the kitchen area, took a key from the small purse she wore slung around her body, unlocked one of the drawers, and took out another key.

“Here,” she said, holding it out toward Sydney. This unlocks the door to my castello — and the gate. You don’t have a purse, but put it on that chain you have around your neck, and wear it under your shirt. If you ever need to, come here.”

“But why? Why are you doing this?”

“Because I don’t know the answer to your questions.” Briskly, Giulia unfastened the chain around Sydney’s neck. “Yes, it goes over the clasp. Good.”

“You said, come here. But where is here?”

“You take a taxi, and you ask to be driven to the tower on Icart Point. This tower is the farthest to the east, one of the few where the cliffs start to climb — he’ll know. And one other thing I will show you.”

Giulia took Sydney by the hand and led her toward the statue of the girl. She reached behind it and the black wall opened.

“Not magic,” said Giulia, laughing at Sydney’s startled face. “It’s a door, a second exit from this place. It leads to what was once a gun emplacement, connected to the tower by a tunnel. I’ll show you when we go out, but we won’t go down it now. We are not dressed for guerilla warfare.”

Outside, Giulia led the way around the curving wall of the tower and stopped.

“See?”

She pointed toward a flat metallic disc about three feet in circumference, set in concrete, that gleamed dully among the plants and grasses. “That can only be opened from the inside. It covers a circular dug-out area where they had a gun — the edge is serrated, very strong, so it was possible to close it off. They made it out of the turret ring of a French tank. But you have to be careful here, because all is not as it seems. Look.”

Giulia picked up a stone and threw it. The stone disappeared.

“Trenches. Overgrown trenches.”

“Esattamente. The stone walls are covered with flowers and plants, almost two feet of them in places.”

Sydney walked forward. Close up, it was comparatively easy to see the opening of the trench nearest to her, in spite of about two feet of ivy, ferns, and a small plant that looked like a miniature cream-coloured lupin. A cultivated rose from the garden of the original house on the property had gone wild, covering the native growth with deep pink double petals, now past their prime. A flash of movement overhead made her look up to see a wraithlike white bird flying silently overhead, its long legs trailing behind its body.

“Heron,” said Giulia. “You don’t see them too often. Like a ghost bird, no?”

A line of poetry that Gil once quoted to her floated into Sydney’s mind. The sedge is withered from the lake, and no birds sing. His beautiful voice that could caress as well as castigate. She’d forgotten she had been wooed by more than the money. She had loved him once. Hadn’t she?

“But now, we can forget about all this.”

“Where are we going?” Sydney asked.

“You like jazz? That’s where we go — and to give you another surprise, I think. Avanti!”

It smelled right. It smelled like the boîtes on the Left Bank she had loved when she danced with the Paris Opera Ballet, the bistros and clubs of Milan when she guested at La Scala, a blend of smoke from Gitanes and Camel cigarettes, the vinous bouquet of wine and the dark golden aroma of cognac and whisky, the faint but sharp undertone of humanity: a tinge of sweat, threads of perfume. A gust of nostalgia for her lost dancing days engulfed Sydney as she and Giulia Vannoni went down the steps beneath an illuminated sign that read “Le Grand Saracen.” Drifting up from below came the sound of music — bass, drums, but mostly piano. The tune was a standard: Cole Porter’s “In the Still of the Night.”

The room they entered was dimly lit, with a cavelike quality suggesting both a return to the womb and something faintly sinister. There was nothing remarkable about the decor, which mostly consisted of a variety of posters from art exhibitions, jazz concerts, and stage shows against dark walls. As they entered, the music ceased, and there was a smattering of applause. The place looked full.

“Well, look who’s here! Giulia Vannoni, la bella donna senza pietà!”

The speaker was a dark-haired woman about the same height as Giulia, but of a different build, slender to the point of almost emaciation. She was dressed in the de rigeur black of the avant-garde, with a pair of huge earrings not unlike the chandelier in Giulia’s castello, kohl-rimmed eyes and a slash of carmine on her long, thin mouth.

“Saluto, Deb. Meet Sydney.”

The two women shook hands, the dark-haired woman frankly appraising Giulia’s companion.

“Oh, yes, now I’ve got it — you’re the wife of —”

“I’m Sydney Tremaine.”

“Okay.” The dark-haired woman smiled, as if she understood the subtext. “I’m Deborah Duchemin. Welcome to the Grand Saracen. Let’s find you a table before they start playing again. Giulia drinks red wine — and you?”

“The same.”

Sydney watched Deborah Duchemin leave. “Why did she call you the pitiless beautiful woman?”

“Oh.” Giulia pulled off her heavy jacket, and around them, heads turned.

The clientele was a mix of very young men and women — a tube top, singlet, and jeans crowd — and a fair number of middle-aged couples still clinging in garments and ponytails to their golden hippie age. A couple of men in business suits seemed to have wandered in after a long day at the office. There were other women on their own or in groups, particularly among the younger set, but no one greeted Giulia, or even acknowledged her presence. She may have been recognized, but she clearly was not a local.

“She wants us to be — what do you Americans say? — an item.”

“And you’re not interested?”

“Of course. But Deb is a complicated woman — capricciosa. She is not for me.”

As Sydney turned round to put the art director’s jacket over the back of her chair, she glanced toward the little platform on which the jazz group was reassembling. There was a bass player, percussionist, pianist. Through the mists of cigarette smoke the pianist looked vaguely familiar.

“Is that — ? No, it can’t be. Can it?”

“It can. That’s the surprise. I recognized him when I saw him this morning. The group is called Les Fénions — which is, so I’m told, island French for do-nothings. La dolce far niente, no? Sometimes they have a sax player. The policeman plays piano. Interesting, don’t you think? The same man and yet one must be so different from the other.”

Sydney looked again. The policeman was wearing a white shirt, open at the neck. She could see a jacket and tie hanging over his chair, and she wondered if he’d come there straight from work. Bent over the keys, a slight smile on his lips, he seemed absorbed in what he was doing as if he were on his own. On a desert island. At this moment, the drums and bass were listening to him as he set up the melody of another Cole Porter standard, “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” with a pure simple sound that gradually began to swing as the other players took up the harmony and rhythm. As the notes became more intricate, the piano player’s body moved slightly, his hands flying over the keys swiftly and surely, free and yet in control. The buzz of conversation quietened.

When the piece came to an end, the pianist turned to acknowledge the applause with the other players. For a moment he looked almost startled. Then he grinned and reached up for a glass that stood on top of the piano.

“Bello, no?” said Giulia.

“It’s an interesting face,” agreed Sydney. “Lean, and just a tad mean. The camera would love him, I think.”

“Deb tells me he has an interest in the club, and the restaurant upstairs. His father owned them.”

“I heard him speaking Italian this morning.”

“His father was Italian, his mother a Guernsey woman. She rescued him or something, I don’t know. Something to do with the war.”

“It sounds romantic,” said Sydney. The piano player looked up from his keyboard, and at that moment he saw her.

“I think he’s seen me,” she said. “And he’s looking more than a tad mean right now. He’s coming over.”

Detective Inspector Moretti was heading across the room, briefly sidetracked from time to time by friends and well-wishers at intervening tables.

“Ms. Vannoni — Mrs. Ensor —” Moretti turned to Sydney.

“Tremaine,” said Sydney. “Sydney Tremaine.”

“Ms. Tremaine,” said the piano player. Her correction seemed to have annoyed him further. “Your husband has reported you as missing.”

“I’m off-duty, Detective Inspector. Aren’t you? I’m Ms. Tremaine when I’m off-duty, so do I call you Detective Inspector when you’re supposedly off-duty?” I’m already slightly drunk, Sydney thought.

“It doesn’t matter to me. I thought you should know.”

“Thank you. Now I do. He is missing me, but I am not missing him. You can call off the search parties, Detective Inspector Moretti.”

Moretti said nothing more. As he turned to leave, Giulia put a hand on his arm.

“Do you take requests?”

“It depends on the request,” he answered.

“‘Mack the Knife,’” suggested Giulia Vannoni.

Her smile challenged him.

He did not respond, but for a moment Sydney thought the piano player would become the policeman, as his expression moved from annoyed to thunderous. He seemed to be on the verge of saying something, but instead he shrugged off her hand that still held his sleeve, turned away, and went back to the tiny stage. She watched as he said something to the other musicians, sat down at the piano, and started to play.

Why can’t you behave — oh why can’t you behave?

Opposite her, Giulia started to laugh.

“The policeman has a sense of humour. Is there a message for us, do you think?”

“Perhaps he thinks the message was for him. Or maybe it’s just Cole Porter night,” said Sydney.

But Giulia’s flippant request disconcerted her. Was there a message for her, let alone for the policeman-piano-player? Was she being a complete fool? Possibly. In her experience, the only way to blind yourself to sense and sensibility was to get drunk, and it seemed she was not yet drunk enough. She reached across the table for the bottle of wine.

Moretti saw them laughing as they left, arm in arm, and his anger returned. The clear night sky outside the club, the sound of halyards clinking against the masts of the hundreds of boats in the Albert and Victoria marinas, the clean bite of the air usually enhanced the tranquility of mind he found in the smoke-filled, half-lit womb of the jazz club. This time he had taken his preferred escape route, only to find reality there ahead of him.

They stopped to say goodnight to Deb Duchemin at the door, and it looked as if Giulia Vannoni was having to hold her companion up, to keep her on her feet.

He thought of the uncontrollable anger of Gilbert Ensor, of the professional consequences for himself if he walked away — which was what he wanted to do, because he was bloody tired, and the whole point of coming and playing a set with the band was to forget about the case and Sophia Maria Castellani, whoever the hell she was, for an hour or two — and the personal consequences for this silly woman with her luminous good looks and her wasted talents. He followed them into the small, well-lit car park, where Giulia Vannoni had left her pricey Ducati.

“Ms. Vannoni —”

He could see from Giulia Vannoni’s eyes she was not sorry to see him.

“You’re not seriously thinking of putting her on the back of that machine, are you?”

“I was going to get a taxi for her.”

“This is not New York or Rome. You’d have to wait. And Gilbert Ensor is an explosive man, Ms. Vannoni. It would be best if she checked into another hotel for the rest of the night until she has sobered up. I will let her husband know she is safe — I’ll say she was visiting friends.”

“Friends? Here?”

“I’ll come up with something.”

“I understand.” Gently, Giulia Vannoni dis-entangled herself from Sydney Tremaine. “Perhaps it would be better.”

Moretti thought she had fallen asleep. She sat beside him in the Triumph, her head dropped on his shoulder. He felt her shift on the seat, heard her sigh.

“I’m drunk, aren’t I?”

“Yes.”

“What’s your name? I mean, your first name. Detective Inspector is too — difficult, when you’re pissed.”

“Ed, I’m called. My full name is Eduardo.”

“Oh right, Italian. Did you know, Eduardo, that Giulia says I can only learn to read in Florence if I become a nun?” Her voice was completely serious.

“Ah,” said Moretti.

There didn’t seem to be anything else to say.