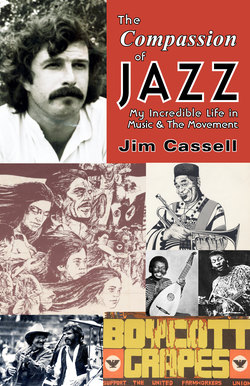

Читать книгу THE COMPASSION OF JAZZ - Jim Cassell - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER

1

The United Farm Workers

The United Farm Workers headquarters needed to move from Delano—it was too small, too dusty, and too small-town for such a big movement. Then Cesar heard about a property going up to bid—an old tuberculosis hospital with acres of land surrounding it (some of Cesar’s relatives had been treated at the hospital while it had been running). It’d be perfect for the new headquarters, but there was a big issue—it was in the middle of Kern County in the Tehachapi Mountains, which was heavily Republican.

Once it became public knowledge that Cesar and the union were interested in the land, powerful conservatives in Kern County were determined to make sure he didn’t get it. A Jewish Hollywood producer who was very sympathetic to La Causa offered to help the union acquire the property. They worked out a plan where Richard Chavez, Cesar Chavez’s brother, would dress up like a chauffeur to drive the producer in a limousine to make a bid on the property. After the Hollywood producer won the bid, he turned the land over to Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers, outmaneuvering the power brokers of Kern County.

The new headquarters were in Kern, California, and were nicknamed La Paz. It was different, though, in the new center. The beauty of the union was that it felt like one big family, full of love and support and united by our common goal of fighting for a better life for the farmworkers. Now it felt a bit like a monastery—everyone was working all the time, without the previous feeling of camaraderie. That isn’t to say it was a bad work environment in the least; every person who worked for the union was a good person. We all worked hard and sacrificed.

When I rejoined the United Farm Workers, I asked Cesar to let me be a photographer, but he said, “No, Jim, I want you to put on more benefits, like you did with Santana,” which I had done when their first album came out. Cesar had Joan Baez in mind, as they had a close personal relationship. This is the first concert I put on from scratch, whereas I had had the Fillmore Auditorium’s help with the previous Santana benefit.

While I was still planning, Steve Miller called and asked to be a part of the benefit, though I have no idea how he had heard about it. When Steve Miller showed up, he told security he was part of the show and called himself “Stevie Guitar Miller.” I am sure the rough-looking chicano security guards didn’t believe him at first.

The concert went really well. It was at the San Jose State football stadium, called the Spartan Stadium. Joan Baez headlined, and Steve Miller, Cal Tjader, a teatro group, and a mariachi band played as well. Joan Baez was very gracious and easy to work with. We called the show Fiesta Campesina, and at least 5,000 people came—it was more successful than we had expected. I had spent months putting the show together, and it could never have been done without all the volunteer effort of the community.

People in the printing trades donated hundreds of hours and money to the cause to print the posters, pamphlets, envelopes, etc. The artist of the poster donated his artwork, and the musicians donated their time to put on an unpaid concert; not to mention all the volunteers it took just to run the event. Cesar and his family came up to see the concert and participate in taking tickets and so on. This concert really set me on the path that led to my becoming a music producer later in my life. I greatly enjoyed the independence of setting up concerts with almost full control over all the variables. I was able to work freely from the Bay Area and wasn’t required to work out of the headquarters.

United Farm Workers march from Delano to Sacramento. (1965)

Cesar Chavez speaking in Sacramento during the march from Delano.

Jim’s first show after meeting with Cesar was with Joan Baez. Here is the promotional photo that was used.

First UFW concert flyer. (1971)

The UFW gave me an old red convertible Valiant slant-head six-engine to use as I set up benefit concerts, and I loved that car. Getting artists to commit to playing benefits, often for free or even at their own low expense, took a lot of work and a soft sort of persistence from me. It was a successful strategy, as we were able to make the Fiesta Campesina an annual concert. Every year it was bigger than the last, with a large variety of artists, both musicians and poets alike. I did other benefit concerts during the year when we weren’t putting on the Fiesta Campesinas. Over the six years that I worked for the United Farm Workers, I produced over twenty-five benefit concerts with a diverse array of artists such as Santana, Cheech and Chong, Crosby Nash, Rita Coolidge, New Riders of the Purple Sage, John Kahn, Merl Saunders, Mike Bloomfield, Philip Whalen, The Charlatans, Taj Mahal, Pete Escovedo and Sheila E, Coke Escovedo, Dakila, Cal Tjader, Steve Miller, Bola Sete, Toni and Terry from Joy of Cooking, Stone Ground, Dan Hicks, Vince Guaraldi, Joan Baez, Eddie Palmeri, Robert Creeley, Red Wing, Luis Gasca, and El Chicano. We had beatnik poets Allen Ginsburg and Lawrence Ferlingetti, Latino rock stars Jorge Santana and Malo, legendary Tex-Mex artists Little Joe y la Familia, Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, funk-soul musicians Tower of Power, country-western singer Kris Kristofferson, and jazz player Eddie Henderson. The poster art for some of these concerts was done by Esteban Villa, who was in the Royal Chicano Airforce, a group of mainly teachers at Sacramento State University who came together and named themselves RCAF as a joke. He often donated his artwork to La Causa, and his paintings were very popular. There were many great posters done by gifted artists, nearly all donated to the UFW.

Summer in Mariposa. Jim in a UFW convertible given to him to produce fundraiser shows. (1974)

All the artists I booked were dedicated to La Causa. Many other people were interested in supporting the cause, but this was during the Nixon era—community leaders were being bought off by government jobs. We had disdain for those who sold out; they were commonly called “poverty pimps.” Unionization was how we were able to protect ourselves, and unions often helped each other out—the International Longshoremen’s Union supported the UFW and helped our cause. They, and several other unions as well as religious and ethnic organizations, would organize food caravans to feed the strikers all over California.

In May of 1972, the then governor of Arizona Jack Williams, who was called One-Eyed Jack by the media, made provisions of the Farm Labor Bill which made it next to impossible to strike during harvest times and prohibited secondary boycotts. It was in direct conflict with what the United Farm Workers were trying to do in Arizona, so we did a huge campaign to reverse One-Eyed Jack’s actions and to support his opposition, even bringing in strikers from across the border. The opposing candidate, Jerry Pollock, didn’t win, but we were able to drum up a lot of attention to La Causa. I worked in Arizona during the lengthy campaign and did a big benefit concert with Little Joe y la Familia, which raised a lot of money and publicity for the union.

I worked for the union for six years, from 1969 to 1975, putting on concerts and benefits and doing all the organizational work that they entailed. Though I believed wholeheartedly in the work the union was doing and still does to this day, I was feeling less and less dedicated as the years went on—I was burning out. Toward the end of my time with the United Farm Workers, I felt the UFW board wanted to control me more, to churn out more concerts than I feasibly could.

The pressure of constantly getting artists to perform for free was starting to wear on me. In 1975, the Board of Directors (Cesar Chavez, Richard Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Philip Veracruz, Pete Velasco, etc.) didn’t okay the project I was working on. I proposed to put on a fairly typical concert at the Sonoma State athletic field with Kris Kristofferson, Rita Coolidge, Taj Mahal, and others. The board questioned the whole show and called me down to La Paz to meet with the board. I felt let down, after all the successful benefits I had done and money and publicity I had raised, to not be trusted with this project.

I took it as a sign that the time to leave the United Farm Workers had come, so I sent Cesar a resignation letter in which I thanked him for the opportunity to work for the UFW but stated that it was time for me to go. I wished them the best of luck, and I will always be a supporter of the United Farm Workers. Years later, Dolores Huerta would occasionally ask me to come back and do concerts after I left, but I had already moved on. I will always be grateful for my time with the union and with Cesar—he was the one who steered me into producing concerts for a living, when I had originally planned to be a photographer. Working for the union was a, if not the, highlight of my life.

Letter from Cesar Chavez authorizing Jim to represent the United Farm Workers and do fund raising. (1972)

Marchers cooling off in an irrigation ditch during the Coachella March from Coachella Valley to Calixico to protest workers being brought in to break the strike. (1972)

Jim resting during the Coachella March. (1972)

Undercover police officers are seen here at the end of the march. Ted Kennedy was also there, as well as many notables from Los Angeles.

Jim and Roberto Garcia. Salinas Valley. (1973)

Dr. Ralph Abenathy at the UFW protest march, Coachella Valley.

Caesar Chavez and Bobby Seale, Oakland. (1974)

Rambling Jack Elliot and Kris Kristofferson at a UFW benefit concert at the Berkeley Greek Theater. (1974) Kris was a real sweetheart and paid his whole band himself to show up and perform.

Jim while working with the United Farm Workers (UFW). (1976)