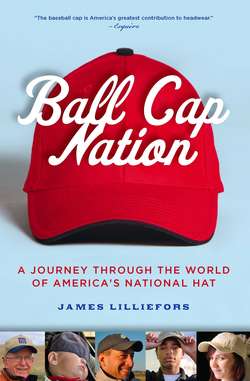

Читать книгу Ball Cap Nation - Jim Lilliefors - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеNotes From the Far Outfield

When I was a kid, baseball caps really were baseball caps. There were no designer caps back then. No cap stores in airport terminals. Celebrities never wore ball caps. Presidential candidates? Not a chance. There was nothing cool about wearing a ball cap. Look at the newsreel footage from, say, Woodstock, in 1969—or any other big event of the time—and count the baseball caps. There weren’t any. The only place you’d see a backwards ball cap in those days was behind home plate, on the head of a catcher.

Our country was different then. If you wanted to wear a ball cap, you had to join a team and play ball. Which was, more or less, the reason I got involved in sports: I wanted to wear the uniform, to be part of the team. I still remember my first sandlot baseball cap—the bright red wool fabric, the authoritative white “M” on the crown, the taut bill that I always curved just a little extra so that it shaded my eyes.

I was, to use a slight exaggeration, an “average” ball player, with a tendency to daydream on the field. I started at shortstop, but they quickly moved me to outfield after a pop fly hit me on the foot. Actually, I was reassigned to what was known as the “far outfield,” which was sort of one position beyond the outfielders. The “far outfield” was where they put the players who were left over after the nine starting positions had been filled. Our team had about twenty-seven players in the far outfield, as I recall. Most of what we did out there was kick at the grass, adjust our caps, and think about stuff besides baseball.

On those rare occasions when a ball was hit to the far outfield, we would all look up, in various states of panic, waiting to see who would step forward to catch it. Some of the far outfielders would do a little dance-and-squint routine, pretending to be getting in position to make the catch. But no one ever did. Once the ball thunked to the ground, we would all run toward it and the one who got there first would pick it up, look at it briefly, and then throw it in the general direction of where we imagined the infield was. Then the real outfielder would take over, although by that point the batter had already rounded the bases at least once. Occasionally, when all of the far outfielders were daydreaming simultaneously, a ball would actually hit one of us.

The league I belonged to was called the MBBL, which stood for Manor Boys Baseball League. I have no idea who the “Manor Boys” were, or why the league was named for them. As I recall, anyone whose parents were willing to pay the “equipment fee” was accepted in the league. At that age (I was nine and a half, going on ten, as we used to say), kids were expected to join stuff, to find out where they fit and where they didn’t. Some were fortunate to discover their callings right away—in this case, they became the pitchers and the home-run hitters; the rest of us wound up in the far outfield. But the good part of the deal was, we all got to wear the caps (and being a member of the team also gave us a license to wear our caps off the field, a license I used liberally).

Our team was known as the Senators, which happened to also be the name of our Major League Baseball team at the time—the Washington Senators (an inspired name, reportedly chosen over such formidable runners-up as the Congressmen, the Vice Presidents, and the House Ways and Means Committee). The teams we played were named for MLB clubs, too, most of them referring to birds, Native Americans, or sock colors.

The sandlot Senators actually beat the big-league Senators once, incidentally, in a historic night game at D.C. Stadium, by a score of, I think, thirty-seven to nothing. Well, okay, not technically. We never really played the Washington Senators. But people used to say that we could beat them if we ever did. That’s because the Washington Senators of the mid- to late-1960s were about the worst team in the history of baseball. Their combined batting average was something like .0057 and their earned run average was, I believe, 21.7. They were the Hamilton Burgers of big-league baseball. There was a saying about the Senators back then: “Washington—first in War, first in Peace, and last in the American League.”

As a kid, though, I didn’t get that. Not at all. I always thought the big-league Senators were on the verge of a spectacular turnaround—like those fallen comic book heroes who suddenly found a hidden reservoir of strength which enabled them to rise up and pummel the bad guys into submission.

Even when the season was winding down, and the Senators were a hundred and fifty games behind, I would listen faithfully each night, sitting under the stars on our back porch in the D.C. suburbs, a nine-volt transistor radio pressed to my ear, my heart thumping as the game went into the top of the ninth with the Senators down by something like 21–0 and Frank Howard coming to the plate.

One of the saving graces about the big-league Senators, my father liked to point out, was that some of the teams that came to Washington to beat the crap out of us really were good. Several times each summer he’d take us downtown to see the Senators play the Yankees, for instance, and we’d get to watch such legendary players as Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, and Whitey Ford. That didn’t excite me a whole lot, though. I was too loyal to the Senators. (In 1972, the Washington Senators were sent away to Texas for rehabilitation, a process that involved, among other things, being co-owned for several years by George W. Bush. It took thirty years before another baseball team came to Washington. There’s a saying about this new team, which is called the Nationals: “Washington—first in War, first in Peace, and last in the National League.”)

The author, right, at age five, wearing his first cap, shares a wagon with his younger brother.

Of course, the sports world was a smaller place then. We had great athletes, but we didn’t yet call them “superstars.” Television networks didn’t pay billions of dollars a year to broadcast baseball and football games. Endorsement deals didn’t double or triple the annual Defense Department budget, as they do now. Merchandising was a modest side business; fans didn’t walk around wearing caps and jerseys advertising their favorite teams.

In fact, if you did wear a cap, of any sort, back then, people tended to think you were a little strange. My mom—who was a wonderful person in every other way—sometimes wore a sad, droopy little cotton ball cap to keep the sun off her face, and it embarrassed at least one of her children to no end. Then there was the old guy at the hardware store who wore a ratty looking yellow mesh-style cap—which was invariably off-kilter and unfastened in the back, as if someone had mistaken his head for a hat rack and just set it there. He always sat in a lawn chair by the front window of the store, by the seed displays, staring out at the parking lot. The first few times we saw him, my friends and I would walk back and forth out front trying to decide if he was “real” or not.

There was also a man named Mr. Hadler (or “Hadler,” as my father called him) who lived down the street from us. Mr. Hadler had to be one of the creepiest people in the D.C. area back then (not counting elected officials). He rarely came out of his house, but always stood behind the screen door, it seemed, smoking a cigarette and watching the street. Whenever we rode past on our bicycles, there he was. We knew very little about Mr. Hadler except that there was a faded “Goldwater” sticker on his car and that the police had gone to his house one night, after he “roughed up” Mrs. Hadler. I overheard my father saying this to my mother, and, of course, had no idea what “roughed up” meant. But it further enhanced the notion in my mind that Mr. Hadler was of a different—possibly alien—species. (Mrs. Hadler, in case you’re wondering, was never seen; the only thing we knew about her was her name: Mrs. Hadler.)

On the rare occasions when Mr. Hadler did come outside, he wore a dirty white T-shirt, carried a can of Pabst Blue Ribbon, and had the strangest-looking thing on his head. It was a ball cap, but unlike any I had seen or would see again—grungy, sweat-stained, of indeterminable color. The reason he came outside was to look at the bushes beside his house and say “Shit” several times.

The only other occasions when I would see ball caps in those days were on our road trips through the Midwest. My father liked to stop at those open-all-night restaurants along the turnpikes, where we would all sit at the counter and have a slice of pie and ice cream and a soda at some ungodly hour of the night. I never felt safe when we did that; I always imagined that the other customers were conspiring to rob us, tie us up, and steal our car. Typically, there would be three or four truck rigs parked outside and two or three men sitting at the counter. The men would be unshaven and drinking coffee, mumbling to themselves, and occasionally staring at my mom. Many of them wore a low-rent cousin of the baseball cap, also known as the “trucker cap.”

And that was it. Besides my mom, only oddballs, aliens, and truck drivers wore ball caps (I should mention here that some of my favorite people are truck drivers). But it was a situation that would change dramatically during the 1970s, for reasons that some of our best minds are still trying to explain. After several ridiculous headwear fads came and went—the “floppy” hat, the headband, the oversized knit cap—baseball caps gradually became acceptable and then, inexplicably, fashionable.

By the mid-1980s, ball caps were becoming a fad, and a burgeoning industry. In 1992, even our Presidential candidates wore them, presumably to show their kinship with the common man and woman. Bill Clinton and Al Gore jogged together wearing their ball caps. George Herbert Walker Bush—at the time known as “George Bush”—wore one on the campaign trail that read, “The Other White Meat.” (Yes, he did.)

In true American style, people soon began wearing them inappropriately, as well—backwards, sideways, indoors, and even in church (see Chapter Eight, “Cap Etiquette”). Caps had become, in a sense, cultural equalizers. When President George W. Bush snuck away from his Texas ranch in 2003 to visit the troops in Iraq for Thanksgiving, his escape was enhanced by the use of a ball cap. These were the President’s own words: “I slipped on a baseball cap, pulled ’er down—as did Condi. We looked like a normal couple.” The classical violinist Joshua Bell in 2007 donned a ball cap, jeans, and a T-shirt and stood by the escalator at the L’Enfant Plaza subway stop in Washington, D.C. for forty-five minutes, playing some of the most gorgeous music ever written. Bell routinely sells out Carnegie Hall, but nobody in Washington even stopped to listen for more than a few seconds.

Yes, caps have become an easy way of seeming “normal”—the goal of a growing number of Americans, apparently. Throw on a ball cap before you go to the store and no one will give you a second look, regardless of what’s underneath. If you haven’t shaved or your skin is full of blemishes, the clerk won’t pay you any mind. If you have two mouths or a tentacle where your left eye should be, no worries. We’re all just normal folks when wearing our ball caps.

Many theories have been proposed as to why we’ve become a “Ball Cap Nation.” The salient one, of course, is that ball caps finally solve a problem that has stymied great thinkers for decades—bad hair days. But does the ascendancy of the ball cap also reflect some fundamental change in the structure of our thoughts and feelings over the past three decades? What does it really mean that we have become a Ball Cap Nation? What does it say about our values, our priorities, and our character? Once you start asking these sorts of questions, it is inevitable that other, related questions will arise. “Why has the ball cap culture spread so rapidly around the world?” for instance. “What’s with the sideways ball cap?” And, of course, “What are the advantages of drying a wet baseball cap on your head?”

All of the above questions will be addressed in these pages. Our experienced reporting team traveled around the country in search of answers, speaking with cap historians, manufacturers, retailers, sociologists, collectors, and an out-of-work vending machine repairman. We visited a few famous cap-wearers, several almost-famous cap-wearers, and a couple of clearly-never-will-be-famous cap-wearers. We even asked former President George W. Bush what he thinks our cap-fixation says about American society, particularly during the eight years of his administration. You can just imagine his answers (you’ll have to, because he declined to respond to our queries).

As our country has grown increasingly diverse and complicated, we have sought—and, occasionally, found—things that unite us. The ball cap feeds an idea that we, Americans, seem to cherish: As different as we all are—despite the fact that some of us stand on the pitcher’s mound while others loiter in the “far outfield,” kicking at the dirt—when we wear a ball cap, we’re all part of the same team.