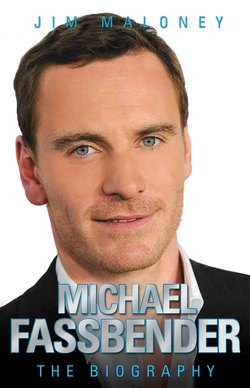

Читать книгу Michael Fassbender - The Biography - Jim Maloney - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

BOY FROM KILLARNEY… VIA HEIDELBERG

ОглавлениеMichael Fassbender stood out from the crowd while he was still at school but this had nothing to do with star appeal or talent. It was because, in a classroom full of O’Sullivans, Kellys, Murphys and O’Connells, his unusual surname at first raised eyebrows among teachers and gave way to some gentle mickey-taking from fellow pupils. His name has continued to intrigue ever since, from casting directors to interviewers. A German Irishman? An interesting mix. ‘I suppose the German side wants to keep everything in control and the Irish side wants to wreak havoc,’ he was later to joke. But he wasn’t being just frivolous with this remark because it does help to explain the two contrasting sides to his character: Michael the focused, methodical, confident actor, and Michael the easy-going, free-wheelin’ charmer.

He was born in the city of Heidelberg in south-west Germany to a German father, Josef, and an Irish mother, Adele. Heidelberg is a city where a pretty Old Town of cafes, shops and restaurants co-exists with a bustling modern business centre and technology park, with an emphasis on science and research. Nestled in the hills of the Odenwald along the banks of the Neckar river, it boasts a castle and the oldest university in Germany. Students, businessmen, scientists and tourists are all attracted to the city, which has something to offer to all of them.

Josef Fassbender was a successful, hardworking local chef who had worked in various hotels in Germany, Spain and England, including London’s famous Savoy. It was in a London nightclub that he met Adele, who had grown up in Country Antrim, Northern Ireland. They began going on dates together and, as their romance blossomed, they eventually married and she moved with him to Heidelberg, where he continued to work as a chef. But Adele missed Ireland and after starting a family she persuaded Josef of the benefits of bringing up their children in the countryside, suggesting that southern Ireland would be ideal and that he could get plenty of work there. So it was that in 1979 they moved to Dromin, Fossa, in Killarney, County Kerry, on the south-west coast of Ireland, with their two children, Catherine and two-year-old toddler Michael.

Fossa is located on the shores of Lough Léin, in the shade of the McGillycuddy Reeks four miles west of Killarney town. The talented Josef became a chef in Killarney’s luxurious German-owned Hotel Europe and later Head Chef at the elegant Hotel Dunloe Castle. Although Adele came from Larne, Country Antrim, her family, generations back, were from the south and family lore has it that she is the great great-niece of the Irish revolutionary hero Michael Collins. As Michael was later to say, ‘We’re only going by my grandfather’s word but I believe it.’

Michael’s maternal great-grandfather was disowned by the family after he joined the Royal Irish Constabulary and moved to the North. He returned years later hoping to be reconciled with his family but they still wanted nothing to do with him.

With Adele’s relatives still living in Northern Ireland, the family would often visit during summer holidays and at Christmas, and Michael remembers how very different things were once they had crossed the border. British army patrols checked cars going in and out during The Troubles and they would have to get out of their car while soldiers searched through the seats and boot for possible guns, ammunition or bomb-making materials.

In the early years in Fossa, when pre-school Michael was four and five years old, he felt a little lonely as all the other boys in his immediate neighbourhood seemed to be three or four years older than he was, so he spent a lot of time on his own and would retreat into a world of his own imaginings.

Adele, who spoke fluent German, insisted they talk it at the dinner table, which Michael found embarrassing as he got older, but it taught him the language and was to be instrumental in launching him to stardom when he auditioned for Quentin Tarantino. But even the daydreaming young Michael never fantasised that he would become a Hollywood star. His thoughts were firmly set on becoming a superhero!

It was when this rather insular, shy young boy started attending the local primary school, a short walk from his home, that he came out of his shell and learned to integrate with children of his own age. The principal of Fossa National School was the former Kerry Gaelic footballer, Tom Long. The 149 boy and girl pupils dressed smartly in a uniform of burgundy jumper, cream shirt, grey trousers/skirts and striped ties. To this day, Michael has many happy memories of his time there. ‘The Irish education system is really top notch,’ he was later to say. ‘At primary school I learned about the battle of Thermopylae and 300 Spartans when I was six or seven years old. There was a real love of learning language and poetry, and we were taught history and geography. It was very well rounded.’

The Battle of Thermopylae took place in 480 BC in ancient Greece, when King Leonidas of Sparta and 1,400 men (700 Thespians, 400 Thebans and the King’s bodyguard of 300 Spartans) bravely defended the pass of Thermopylae to the death against a much greater force of invading Persians. This knowledge was to come in useful many years later when he found himself portraying a Spartan warrior caught up in the famous conflict in the movie 300.

Despite his grounded education, Michael still had his head in the clouds and when on his own he enjoyed daydreaming and fantasising of heroic adventures far from Killarney. Such was the strength of his imagination that when he was six years old he was convinced that he was a young Superman. At night in bed he would hear a buzzing in his ear and thought it was Kryptonite calling him to the garage – although he wasn’t sufficiently fearless to get up to investigate! Michael was delighted when his parents bought him a Superman outfit. Now there was no stopping him. They could hardly get him to take it off and had to put up with him leaping and jumping heroically around the house. And all this really made his flying take off – or so he thought.

‘I would practise leaping off the couch and when my sister came in I’d say, “Look, look, I’ve flown a little further!”’ he remembers. ‘I wanted to take it [the outfit] to the swimming pool so I could practise my flying but my parents wouldn’t let me.’ And what he couldn’t do for real he recreated in the finest traditions of stage and cinema trickery. ‘I used to play this game with my cousin where he would dress up in civilian clothes – like Clark Kent – and he would stand by the side of the road and when a car came he would run behind a bush and I would come out from the bush dressed as Superman.’

Michael has described these childhood years as ‘living in little pockets of fantasy’ – flying a spaceship, climbing trees and pretending to be the Six Million Dollar Man or the Fall Guy, two of his favourite TV shows, starring Lee Majors. Irish television imported a lot of American shows like this – CHiPs, Magnum P.I., The A-Team, Knightrider – and they were firm favourites with Michael and many other children. Michael had an uncanny knack of being able to reproduce a very accurate impression of each show’s theme tune, making guitar sounds and drumbeats with his mouth. It’s something that he can still do and which he describes as being almost OCD [obsessive compulsive disorder]. Among his party pieces these days are the remarkably realistic bird-calls that he learned as a child, the sound of a motorbike or a Formula 1 racing car and the beeping of a pedestrian crossing signal!

In particular Michael loved Tom Selleck, who played Magnum, a private investigator living on Oahu, Hawaii, with a penchant for colourful Hawaiian shirts and shorts. And Michael yearned to grow a bushy moustache like his when he got older! ‘I loved Tom Selleck. He did such a great job on Magnum P.I.,’ he recalled. ‘I don’t think many men can carry off wearing shorts like that!’ Oddly, his childhood knowledge of the show was also to resonate with Tarantino years later.

Inspired by such TV shows, the historical stories at school and the beautiful Killarney countryside, Michael would take himself off for hours at a time, sometimes playing with friends he had made at school, at other times alone. His parents felt that Killarney was a safe place for him to explore and play and, as long as he was back home for dinner at 5.30pm, they encouraged him to enjoy the outdoor life.

One film he was desperate to see was Jaws. His parents told him he would have nightmares about man-eating sharks if he did but they relented when his grandmother persuaded them that he would be fine. He should have listened to his mum and dad. The night after watching it he laid in bed, feeling very frightened and vulnerable, and fearing that a huge shark was lurking in the shadows below him.

Another film he really wanted to see was based on the comic-book adventure Flash Gordon. He was very excited when Josef took him and his sister Catherine to the local cinema in Killarney. But such was its popularity that they had to join a long queue and, despite waiting what seemed like an age to get in, they were turned away after the cinema became full to capacity. Michael can clearly remember his disappointment to this day. Another letdown came after they got a VCR for their home and bought a videotape of ET. Michael and Catherine were terribly excited and could hardly wait for their dad to put it on. Poor Josef then had to tell them that the tape was incompatible with their player.

One day at school, when he was six, he had a little ‘accident’ in the classroom. There was a rule that pupils were only able to use the toilet at lunch break or at the end of the day. Michael was unable to contain himself and a little puddle started to form underneath his chair. ‘I think the teacher was more embarrassed than I was,’ he remembers. But one thing that did embarrass him was public speaking. Never one for reading – unlike the studious Catherine – the quiet and shy young Michael felt terribly self-conscious whenever he was asked to read aloud at school. But at home he was much bolder and less inhibited and, as his hero worship of Superman gave way to that of Michael Jackson, he would try to copy his dancing whenever he heard his music or watched him on television.

‘It was a happy childhood, for sure,’ he recalled. ‘Killarney is such a beautiful place. What’s special about Ireland is that we are steeped in storytelling, whether it’s poems, songs or novels. To have that rich involvement in the arts has influenced me. I guess that’s why I do what I do.’

His secondary school was St Brendan’s College, situated near St Mary’s Cathedral and close to Killarney’s National Park. The impressive grey stone building with arched windows was initially built as a seminary where students were prepared for ordination as priests. Founded by the Bishop of Kerry, David Moriarty, it opened its doors on 16 May 1860, on the Feast of St Brendan, and was known then as the Bishop’s New Palace and later St Brendan’s Seminary. Bishop Moriarty and two priests lived in the upper part of the building and students were taught downstairs. Over the decades, the building grew in size as more classrooms, a science lab, showers and toilets were added and it became a mainstream school with a uniform of blue shirt, tie, navy jumper and grey trousers. Sport was an important aspect at the college, particularly Gaelic Football, and many former students have gone on to sporting glory. Up until the late 1960s the college was mainly staffed by diocesan clergy, with a priest acting as President and school principal, but gradually lay teachers took over these roles. By the 1970s its official title had become St Brendan’s College but it is still widely known as ‘the Sem’ by teachers, students and locals.

Just as he’d had to do at primary school, Michael frequently had to explain his surname. Fassbender translates as ‘cooper’, Fass meaning ‘barrel’ and bender the person who made the barrels. But kids being kids, they were not interested in such humdrum explanations and took great delight in calling Michael ‘Slowbender’.

After hearing from the parish priest, Father Galvin, that the spirit of God was always right next to them, Michael would make room for the spirit in his bed at night. ‘I’d make room for the teddy bears, Jesus and me,’ he smiled. At the age of 12 he became an altar boy and was given the responsibility of holding the keys to the church, which he had to open in the morning and lock at night. On a couple of occasions he overslept and, in a panic, rushed across fields to the church to find the whole congregation waiting to be let in.

Michael was later to liken performing in a solemn Catholic church ceremony – mass, baptism or funeral – at the altar to being on stage. ‘The suspension of reality – the idea that wine turns into blood and bread turns into flesh – was a very visceral thing to deal with, and the ritual and theatre of it.’ But, he always wondered, why did he need to go to a priest for confession? If God was always by his side, why couldn’t he communicate directly with him?

As a shy 12-year-old, Michael’s pastimes included making a bamboo bow and whittling tree branches into arrows for archery. He had a natural musical ear and learned to play the guitar and the accordion. Each week he attended Fossa Youth Club and joined in when some of them entertained local senior citizens, playing the accordion and being part of the dance team.

Josef was keen that his son should work hard at school and Michael remembers him as being difficult to please. ‘If I came home with eighty per cent in a test, he’d ask, “What about the other twenty?” My dad drove it home to me that, if you’re going to do something, do it properly.’ This has certainly been his approach to acting. His intense preparation for each role would often amaze his co-actors and directors.

Adele also inadvertently helped to shape her son’s future career. She had a passion for arts and loved movies. The German film director Rainer Werner Fassbinder – known as the ‘enfant terrible’ of the New German Cinema during the 1960s and 1970s for his provoking and often disturbing films – was one of her favourites. Although he was no relation to Josef Fassbender – and the spelling is different – Michael always joked that the similarity of names was one of the reasons why his mother had married Josef.

Adele was particularly fond of 1970s American cinema. Her favourite actor was John Cazale, who played Fredo Corleone in The Godfather and Sal in Dog Day Afternoon. Sadly he died of cancer in 1978 at the age of 42, having made just five feature films. They are all widely regarded as classics, however, the other three being The Conversation, The Godfather: Part II and his final film, The Deer Hunter.

Michael became as big a fan of Cazale as his mother, along with the stylish yet naturalistic crime films of the era, including Mean Streets, Serpico and Taxi Driver. ‘It was a golden era and Cazale didn’t put a foot wrong with his movie choices,’ Michael once explained. ‘He played unappealing, cowardly, sickly characters. He was very good at releasing any ego and bringing these characters to a very real space without making them very clichéd.’ Cazale would be a big influence when Michael turned to acting. Other actors he admired included Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Gene Hackman, Sean Penn, Robert Mitchum and Montgomery Clift.

As the awkward adolescent years kicked in, MagnumP.I. was usurped as his favourite TV show by WonderWoman. This starred Lynda Carter as a sexy superhero who would quickly change into her skimpy outfit of tight, cleavage-enhancing bodice, pants and knee-high boots, via the aid of TV visual effects of super-fast revolutions and a flash of light. ‘I was always trying to capture her between the change,’ Michael recalled. ‘I felt unusual things were happening to me and I didn’t understand. Cartoons might be on the other channel but I no longer wanted to watch them.’

He remembers, too, the excruciating experience of Josef sitting him down and giving him the ‘sex talk’. ‘I was like, “Oh God, why does he have to do it?” I think I was thirteen and I had a girlfriend. It was embarrassing as hell, like “Urgh!” I knew about all that anyway – you know, boys at school, who’d picked it up from older brothers and cousins.’

Adele, who enjoyed singing around the house, encouraged Michael’s musical talents. In traditional Irish fashion he started by playing the tin whistle and then progressed to the piano accordion. He really wanted to play the violin but his parents told him that violins would be too expensive to buy. Later, like many teens the world over, he picked up a guitar and dreamed of being in a band. In Michael’s case, it was to be the lead singer in a heavy-metal band. He particularly admired Kirk Hammett, lead guitarist with Metallica. But although Michael grew his hair long and was adept at flamboyant rock-star posturing with the guitar in his bedroom, when he heard how good some of his friends were playing the guitar in reality, he knew that he was just not good enough.

It was questionable, too, whether he had the true rock-star temperament. On one occasion he and a group of friends travelled to Dingle where they were going to busk on the streets but they were put off when it started to rain. They persuaded a local publican to let them play inside his pub but heavy-metal music at lunchtime was not of great appeal to his customers and they were repeatedly told to ‘turn it down’. Eventually they were playing with unplugged electric guitars before deciding to give it up as a lost cause!

In 1993 Josef and Adele took over a popular restaurant called West End House in the town centre, opposite St Brendan’s. Josef worked in the kitchen and established a reputation for excellent but unfussy French bistro food, while Adele was front of house. But the first few years were tough and when Michael asked for trainers and fashionable clothes, he would often be told that they couldn’t afford it. It taught him the value of money and of hard work. Nothing comes easy. But Michael and Catherine were somewhat spoiled with the beautiful meals that they got to eat in the restaurant. A particular favourite of Michael’s was his father’s rack of lamb and even now Michael follows the way Josef taught him to do it. He was later to describe his father as being ‘an artist in the kitchen’.

Michael earned pocket money by helping his parents at their restaurant, washing up and waiting on tables. He later remarked that it was good training for an actor being ‘front of house’ where you need to be smiling and looking happy no matter what turmoil is going on in the kitchen or in your own life. His parents made sure that he put away half the money he earned as an investment for the future.

When he was 16 Josef and Adele let Michael live above West End House during the week in exchange for doing weekend shifts downstairs. The restaurant was three miles from home and he enjoyed the independence this gave him. He spent much of his spare time wandering through the beautiful Killarney National Park, nestled among the mountains, with its acres of woods, lakes and grassland where red deer roam. The area is steeped in history. Here, on the edge of a lake, stands romantic Ross Castle, built by O’Donoghue Mór in the 15th century. It came into the hands of the Earls of Kenmare, who owned an extensive portion of the lands that are now part of the Park, and was the last stronghold in Munster to hold out against Oliver Cromwell’s forces, eventually succumbing to General Ludlow in 1652.

Despite Michael’s interest in films, he never even thought about acting at that stage. He admits to being an average student with no real idea what he wanted to do with his life – ‘pretty clueless and irresponsible’. Unlike his academic sister, Catherine, who loved reading and was always asking questions, he was much more interested in his imaginative world and doing physical things, such as playing in the park and climbing trees. Sometimes he would ‘skive off’ school with a friend, Ernest Johnson. Whenever Michael got nervous about it, Ernest would take the philosophical approach and ask, ‘What’ll it matter in a hundred years’ time?’ This phrase stuck with Michael and whenever he had concerns about taking certain acting roles he would just remember Ernest’s words and get on with it. The philosophy also chimes with that of director Steve McQueen, who Michael was to meet some 17 years later – ‘We’re all going to die anyway, so we might as well just get on with it’ – a phrase that Michael has often repeated.

For a time Michael considered a profession in law but, being only an occasional and slow reader, he felt that he would not be able to keep up with the many legal books and documents that he would need to plough through during his studies. Architecture was another idea that evaporated after he failed his technical-drawing exam. His thoughts then turned to journalism and he particularly fancied being a war reporter. He hoped to do well enough at school to be able to go to college in Dublin but fate was to lead him in another direction.