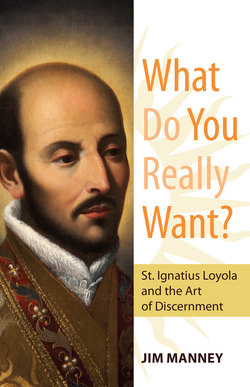

Читать книгу What Do You Really Want? St. Ignatius Loyola and the Art of Discernment - Jim Manney - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

What Is “God’s Will”?

The purpose of discernment is to find “God’s will.” Ignatius himself said as much. What we’re after, he wrote, is to “seek and find the divine will.” But what does that mean? Does God have everything mapped out for us—a blueprint for our lives that we need to discover and conform to? Does God have one “correct” choice in mind for every important decision? In small decisions does he have a precise idea of how we should live every day? “God has a plan for you”: It’s a pretty common idea. God’s will is something external to us; we have to figure out the plan and follow it.

But this is unlikely to be the case. For starters, logically, where do you stop? If God has one right answer for every question, you can’t draw any line with God’s plan on one side and our personal choice on the other. God must know which project you should work on tomorrow morning, what you should cook for dinner tonight, which errands to run, and which route you should take as you do them. He must know the music you should listen to and the best television programs to watch. The “one answer” principle quickly becomes untenable. It’s also incompatible with the free will that God has given us. God gives us wide latitude and much room for discretion. He wishes us to freely choose to love. He doesn’t coerce or limit us.

Another point: Most Christians, including most of the saints, don’t get God’s certain answer to the questions they ask. Sometimes they do. Christ appears to Paul in a blinding vision. God speaks to Augustine through a Scripture passage that the future saint reads at random. But these cases are the exceptions—presented as miracles—to God’s intervention in the usual course of events. Far more common is uncertainty, even wandering in the darkness for a while. If discernment means finding the one right answer to every question, why is it so rare?

In fact, many things are good. The good is plural. God is abundant, not limiting. Most of our choices are among good, better, and best—not right and wrong.

What is God Like?

Our notions of what “God’s will” means is rooted in what we think God is like. The totality of God is beyond our knowing. What we have are images of God—pictures in our minds that capture part of God’s essence. These images are powerful, and they influence the way we think about choices. Growing up, most of us learned a simple image of God as the Boss who is in charge of everything (except when, mysteriously, he seemed not to be). There are variations on the Boss. Some bosses are stern judges enforcing the rules with punishments. Some are hard taskmasters, demanding much and upholding high standards. Some are benevolent, tolerating just about everything with a kindly smile.

As we go on in life other images of God usually appear, but the image of God-as-Boss is a powerful one, and some features of it can persist. We can continue to see God as somewhat separate from creation—overseeing the world from the corner office or the penthouse. We can see him as primarily the solver of problems. This causes us to see discernment as essentially a matter of solving a puzzle, with the lingering fear of making a mistake.

Ignatius’s image of God was very different, and it shaped his whole understanding of the process of discerning God’s “will.” He developed this image in some detail at the end of the Spiritual Exercises in a series of meditations known as the Contemplation to Obtain the Love of God. It’s actually several images of God.

Here’s the first image:

This is to reflect how God dwells in creatures: in the elements giving them existence, in the plants giving them life, in the animals conferring upon them sensation, in man bestowing understanding. So He dwells in me and gives me being, life, sensation, intelligence; and makes a temple of me, since I am created in the likeness and image of the Divine Majesty.

If you’re looking for the heart of Ignatian spirituality, here it is. “God dwells in creatures,” and “creatures” has the widest possible definition. God is present in all things. This is Paul’s image of God: “For from him and through him and to him are all things” (Rom 11:36). Ignatius said that his friends “should practice the seeking of God’s presence in all things, in their conversations, their walks, in all that they see, taste, hear, understand, in all their actions, since His Divine Majesty is truly in all things.” The Jesuit theologian St. Robert Bellarmine went even further. “What various powers lie hidden in plants! What strange powers are found in stones,” he said.

Some Christians are acutely sensitive to God’s absence from the world. Ignatian spirituality emphasizes his presence. This brings God down to earth; “Christ is found in ten thousand places,” said the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. It elevates earth to God; Hopkins also wrote, “the world is charged with the grandeur of God.” “Nothing human is merely human,” writes the theologian Ronald Modras. “No common labor is merely common. Classrooms, hospitals, and artists’ studios are sacred spaces. No secular pursuit of science is merely secular.” Everything that deepens our humanity deepens our knowledge of God.

The Ignatian God doesn’t dwell in lonely splendor in the highest heavens. He doesn’t even sit in the corner office. He’s here.

The Contemplation continues:

Consider how God works and labors for me in all creatures upon the face of the earth, that is, He conducts Himself as one who labors. Thus, in the heavens, the elements, the plants, the fruits, the cattle, etc., He gives being, conserves them, confers life and sensation.

Here Ignatius sees God as the worker—“one who labors.” God the king, the judge, the merciful forgiver, the gift-giver, the unfathomable Other is also the creative power sustaining, healing, and perfecting the world. In the Ignatian view, something is always happening.

The creator God of Genesis is a worker. He doesn’t create out of nothing; he brings order to chaos. Before he set to work, “the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep” (Gn 1:2). Out of this unpromising raw material came the sun, the moon, and the stars; day and night; the land teeming with plants and animals; and, eventually, us. This is Ignatius’s God—a God who never stops creating. He’s at work now bringing order out of the chaos of our world. The Holy Spirit of God moves through this seething mass of passion, energy, conflict, and desire giving us culture, religion, art, science, and all the other elements of our familiar world.

This is why discernment is important. We have a role to play in this creative work. Most of it isn’t glamorous work. “Smiting on an anvil, sawing a beam, whitewashing a wall, driving horses, sweeping, scouring, everything gives God some glory,” writes Gerard Manley Hopkins. “To lift up the hands in prayer gives God glory, but a man with a dung fork in his hand, a woman with a slop pail, gives him glory too.”

The Contemplation ends with a final vision of God as the infinitely generous, inexhaustible giver of gifts:

To see how all that is good and every gift descends from on high. Thus, my limited power descends from the supreme and infinite power above—and similarly with justice, goodness, pity, mercy, etc.—as rays descend from the sun and waters from a fountain.

God dwells in all things; he works in all things; he makes us a gift of all things. He’s like the sun, and his gifts are like the sunshine. The sun is sunshine. God is gift, and the sun always shines.

“What does it matter, all is grace,” are the dying words of the lonely, forgotten, anonymous priest in the novel The Diary of a Country Priest. They echo the last words of St. Thérèse of Lisieux: “Grace is everywhere.” The Spiritual Exercises end on this note—with a numinous vision of light and water, with all as grace, with gifts coming to us endlessly from God, who is Love itself.

A Personal God

Ignatius emphasized one other aspect of God’s character that’s important for discernment. God is personal. He is very close to us. Ignatius imagines God looking on the world in all its splendor and suffering: “the happy and the sad, so many people aimless, despairing, hateful, and killing, so many undernourished, sick and dying, so many struggling with life and blind to any meaning. With God I can hear people laughing and cursing, some shouting and screaming, some praying, others cursing.” God’s answer to this spectacle is to say, “Let us work the redemption of the whole human race.” The remedy is Jesus, who enters into it all. God enters into our suffering by sharing it. Jesus comes to heal and redeem. Jesus “does all this for me,” Ignatius writes.

Friendship is a term often used in the Ignatian tradition to describe our relationship with God. Ignatius frequently urges us to speak to God intimately, “as one friend to another, making known his affairs to him, and seeking advice in them.” Pope Francis often talks about Christ as our friend. “He is close to each one of you as a companion,” the pope said. He is “a friend who knows how to help and understand you, who encourages you in difficult times and never abandons you. In prayer, in conversation with him, and in reading the Bible, you will discover that he is truly close. You will also learn to read God’s signs in your life. He always speaks to us, also through the events of our time and our daily life.”

The Jesuit spiritual director William A. Barry says that friendship is the purpose of creation. “God desires humans into existence for the sake of friendship,” he writes. He says that developing a relationship with God is “analogous to the kind of friendship that develops over a long time between two people.” He draws out the contrast between this friendship and conventional images of God. God our friend is not God the majestic, all-powerful, and distant ruler. It’s not God as lawgiver and judge. As Father Barry’s Irish mother put it, “God is better than he’s made out to be.”

A God who wants friendship with us, who’s present in all things, who labors ceaselessly to save and heal the world, who pours out blessings like an endlessly flowing fountain—a God like this isn’t an Engineer-in-Chief laying out a blueprint for everyone’s life. Our job isn’t to follow a set of divine instructions but rather to grow closer to a God who loves us and desires to be our friend. As we love him more, we will discern the right path. “Let the risen Jesus enter your life—welcome him as a friend,” says Pope Francis. “Trust him, be confident that he is close to you, he is with you, and he will give you the peace you are looking for and the strength to live as he would have you do.”

What Do You Really Want?

This brings discernment into clearer focus. Discernment is about loving and following God, not struggling to make the “right” decision. Our end is union with this God who loves us and who desires the best for us. Our decisions are the means to this end. As Ignatius put it, “I ought to do whatever I do, that it may help me for the end for which I am created.” The Gospel story of Martha and Mary is about this very thing. When Jesus came to visit, Martha busied herself with the chores of hospitality while Mary sat with Jesus and listened to him. Jesus chided the busy Martha: “You are worried and distracted by many things; there is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part” (Lk 10:41-42). The main thing in discernment—the one necessary thing—is to love God first.

If we love God first, it doesn’t matter if the path we follow in life is circuitous, with frequent loops, retreats, and cul-de-sacs. It matters little if the decisions we make turn out very differently than expected. No one knew this better than St. Ignatius. He called himself “the pilgrim.” In the tradition of pilgrimage, the journey itself is at least as important as the goal. His path in life was a meandering one, but Ignatius deeply believed that we can confidently walk along that path, finding the course that pleases God and brings us the deepest joy.

Notice the positive view of human nature that underlies this attitude. Ignatius was no Freudian. He knew nothing of libidos and ids and Oedipus complexes, and would have rejected the claim that they drive our behavior. He was no Calvinist; he didn’t think that the human soul was so irreparably damaged by sin that it is incapable of knowing the good. He didn’t view desires with suspicion as many religious people do. Ignatius loved desires. In the Spiritual Exercises, he continually says, “Pray for what I want.” He believed that our deepest desires—what he called the “great desires”—are for loving union with God and others.

Thus we arrive at perhaps Ignatius’s greatest insight in the matter of discernment. God placed these great desires in our hearts. Finding God’s “will” means discovering what they are. This is what we really want. Ignatius believed that when we find what we really want, we find what God wants too.

Ignatius came upon this insight through his own experience of conversion. Through a process of reflection and discernment he came to understand that his deepest desire was to surrender himself completely to Christ and to go wherever Christ sent him. This desire had always been there. He had been restless and unhappy in his life as a military man and court official. When he recognized his deepest desires—when he discovered what he really wanted—he found peace and joy.

You might say that of course God wanted Ignatius to walk the difficult and demanding path of celibacy and poverty. That God wants everyone to do the hardest thing. But God doesn’t work that way. Ignatius found the way of life best suited for him. If he had been a different person, it’s entirely possible that a career of service to the king would have given him more happiness than a life as a priest. In fact, that must have been God’s desire for any number of young men in sixteenth-century Spain. But it wasn’t his desire for Ignatius, and it wasn’t Ignatius’s deepest desire for himself.

Finding what you really want doesn’t mean “follow your bliss” or “do the work that makes you happy.” The problem is that we don’t know what will make us happy. Following our bliss frequently makes us miserable. We want many things, contradictory things—money and a balanced life; relationships and excitement; the esteem of others and the satisfactions of humble service. The hard work of discernment involves sorting through these desires and wants and passions and needs and discovering the kernel of authentic desire that God placed within us.

“Love God and Do What You Will”

“God’s will” isn’t something external. It’s internal. It’s implanted in our hearts. Doing God’s will isn’t a matter of finding out some undiscovered item of “God’s plan” and putting it into effect; it’s more a matter of growing into the kind of person we’re meant to be. It’s the expression of the deepest truths of ourselves within the setting of a day-to-day relationship with God. The question to ask is, Is this action consistent with who I am and want to become?

We can answer this question with confidence if we sincerely love God and seek to follow in the footsteps of Christ. Here’s the solution to the paradox of discernment. On the one hand, God cares about us and knows us intimately. We’re supposed to follow him in everything, large and small. On the other hand, God has given us free will and reason. We’re free to do what we want. These two principles seem to pull in opposite directions—but they are really two sides of one thing. If we love God, then what we most deeply want and what God wants are the same thing. Augustine made this point in his famous saying, “Love God and do what you will.” If you truly love God, doing what you want will be doing what God wants.

It’s simple—but not easy. The question “What do you really want?” is difficult to answer. We want many things. Many of them aren’t worth having. Many will make us miserable instead of happy. Ignatius knew this very well. He developed an approach to discernment that helps us sift through our competing desires. It’s an approach based on learning to listen to what our heart is saying.